21. Young America

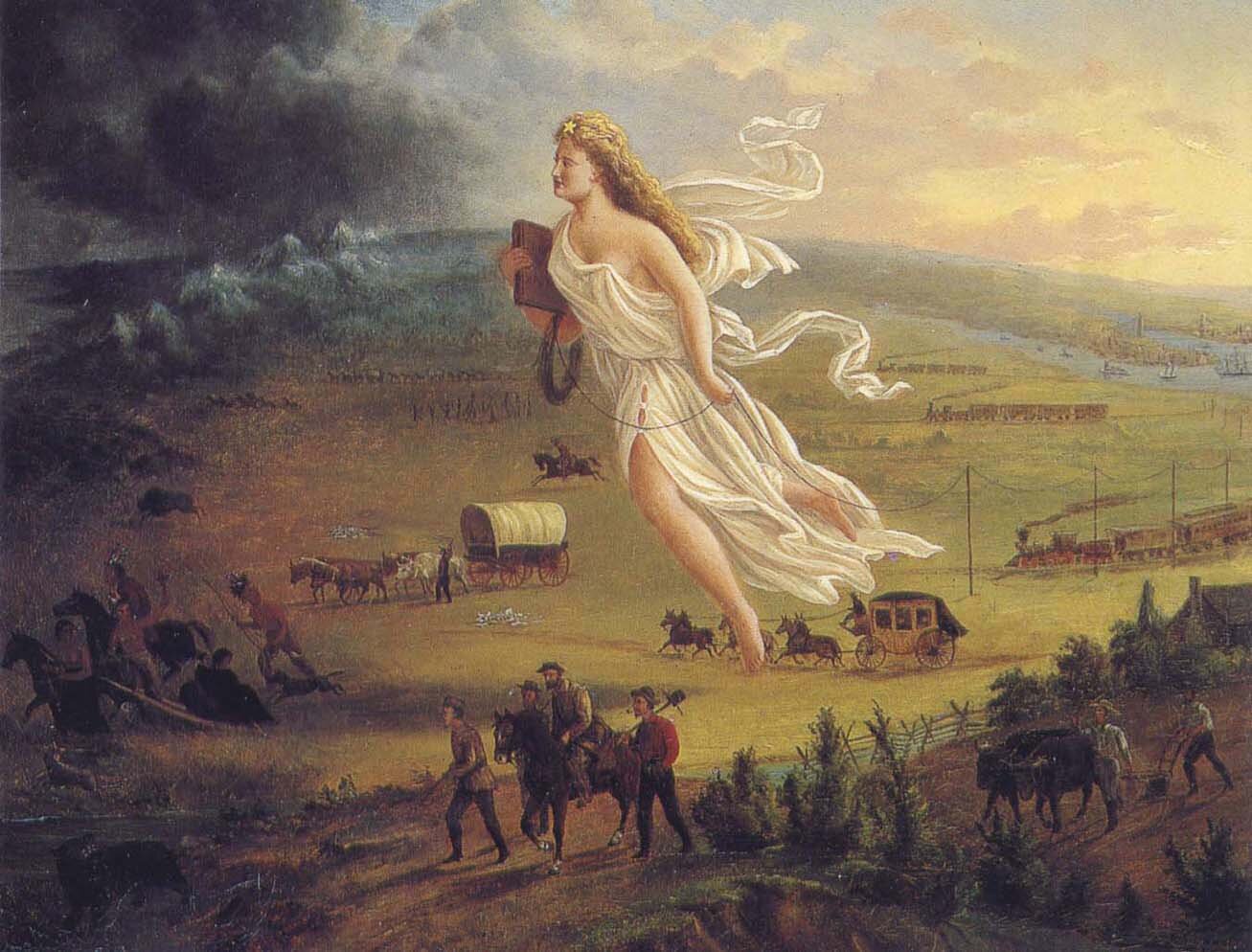

Manifest Destiny

Historian William E. Weeks has noted three key themes that lent support to the notion of Manifest Destiny: the virtue of the American people, their mission to spread their institutions and the destiny under God to remake the world in the image of the United States.[1] The origin of the first theme, later known as American exceptionalism, was often traced to America’s Puritan heritage, particularly the Rosicrucian John Winthrop’s famous “City upon a Hill” sermon of 1630, in which he called for the establishment of a virtuous community that would be a shining example to the Old World.[2] Illuminatus Thomas Paine, in his influential 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, echoed the notion, arguing that the American Revolution provided an opportunity to create a new, better society. John O’Sullivan (1813 – 1895), editor of the Democratic Review, is generally credited with coining the term Manifest Destiny in 1845. The Democratic Review in New York City was the center of the Young America Movement, which was inspired by European reform movements such as the Young Hegelians, Young Germany and Mazzini’s Young Italy, who in league with the B’nai B’rith, the Ku Klux Klan, the Knights of the Golden Circle, and with backing from the European Rothschilds, played a formative role in the American Civil War.

The revolutions of 1848 drove so many Jewish refugees to the United States that several organizations were formed to aid them, including the Free Sons of Israel, founded in New York City in 1849, and affiliated with the B’nai B’rith, the oldest national Jewish fraternal order still in existence.[3] Though the term “Forty-Niners” refers to the wave of settlers who move to California in search of gold in 1849, the failed Revolutions of 1848 spurred the significant immigration of “Forty-Eighters,” including many Jews, to America. As Jews came to be viewed as the hidden hand behind the upheavals, large-scale anti-Jewish riots and pogroms broke out all over Europe, continuing after the revolutions were suppressed in 1849. With various governments that had regained their power now executing revolutionaries, the only option for many of them was to flee. Between 1840 and 1850, the number of Jews residing in the United States climbed from 15,000 to 50,000. The Free Sons of Israel were founded by nine Jewish men who, like the B’nai B’rith, were Freemasons and Odd Fellows. It still uses regalia, passwords, ritual and is organized in lodges governed by a Grand Lodge.[4] Hirsch Heineman, a founder of the B’nai B’rith, served as the first Grand Master.[5]

In 1852, Mazzini sent the most famous of all the 1848 European revolutionaries, Lajos Kossuth, and his right-hand man Adriano Lemmi (1822 – 1896)—Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy and a purported successor as head of the Palladian Rite—to the United States to organize Young America lodges in revolutionary strategy.[6] In the United States, according to Nicholas Hagger, in The Secret Founding of America, Mazzini spearheaded a plan in league with the Rothschilds, to foment the Civil War, along the divide of the volatile issue of race.[7] The Mazzini-Rothschild conspiracy devolved from Southern Jewish community networked with secret societies of the Skull and Bones, the Knights of the Golden Circle, and the KKK who advanced that cause of slave-ownership against the abolitionists of the North. Civile War general Albert Pike, Grand Master of the Southern Jurisdiction of the Scottish Rite in Charleston, was the “chief judicial officer of the Klan.”[8] The Rothschilds, explained Hagger, wanted to start a central bank in America, as the second Bank of America, created by James Madison in 1816, had collapsed in 1836. James Mayer de Rothschild—a defender of the Sabbateans—and his brother Nathan’s son, Lionel de Rothschild, a friend of Benjamin Disraeli, were behind the funding of both North and South in the planned division.

The Rothschilds’ funding of the North was conducted through August Belmont (1813 – 1890). Belmont, whose real name was August Schoenberg, was a German-born Jew who would become party chairman of the Democratic National Committee during the 1860s, and the founder of the Belmont Stakes, third leg of the Triple Crown series of American horse racing. Belmont began his first job as an apprentice to the Rothschild banking firm in Frankfurt. In 1837, he set sail for Havana where he was charged with the Rothschilds’ interests in the Spanish colony of Cuba. In the financial recession and Panic of 1837, like hundreds of American businesses, the Rothschilds’ American agent in New York City collapsed. As a result, Belmont stayed in New York and began a new firm, August Belmont & Company, and restored the Rothschilds’ wealth.[9]

James Rothschild controlled the South through the Rothschild agent Judah P. Benjamin (1811 – 1884), a Southern lawyer and politician who came to be known as “the Jewish Confederate.”[10] Both Sephardi Jews from London, Benjamin’s parents, Philip Benjamin (1780 – 1853) and his wife Rebecca de Mendes (d. 1847) moved from London and eventually to Charleston around 1821, with their daughter and son Judah, who had been born in St. Croix. Philip Benjamin was a member of the Reformed Society of Israelites, which broke away from the Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim. Benjamin was often called the “brain of the Confederacy,” and was featured on the Confederate two-dollar bill.[11]

Benjamin’s political success was due to his advocacy of states’ rights and slavery alongside his promotion of commercial development.[12] “In antebellum America,” according to David Goldenberg, the Curse of Ham “was the single greatest justification for maintaining black slavery, and for keeping that social order in place for centuries.”[13] The Curse of Ham also received the support of Freemasonry where it served to justify the exclusion of blacks. The first justification was articulated in Anderson’s Constitutions of 1923, where he outlined the legends of Freemasonry as well as its regulations or charges, including the “ancient landmarks.” As noted by Michael W. Homer, Lawrence Dermott—the first Grand Secretary of the rival Grand Lodge of Antients, organized in London in 1751, and who took a design by Rabbi Leon Templo as the basis for its coat of arms—published Ahiman Rezo, a history which provided one of the foundations upon which some American Masons could rationalize that Ham’s descendants, who they believed were black, were ineligible to join their lodges.[14]

As revealed in the Financial Times, Nathan Mayer Rothschild and James William Freshfield, founder of Freshfields, benefited financially from slavery, as records from the National Archives show, even though both have often been portrayed as opponents of slavery. On August 3, 1835, in the City of London, two years after the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act, Nathan Rothschild and his brother-in-law Moses Montefiore came to an agreement with the chancellor of the exchequer to issue one of the largest loans in history, to finance the slave compensation package required by the 1833 act. The two bankers agreed to loan the British government £15m, with the government adding an additional £5m later, totaling 40% of the government’s yearly income, equivalent to £300bn today. It was the biggest bail-out of an industry as a percentage of annual government expenditure, dwarfing the rescue of the banking sector in 2008.[15] The money was not paid back by the British taxpayers until 2015.[16] Sadly, the funds were not intended to include reparations to the freed slaves or to redress the injustices they suffered. Instead, the money went exclusively to the owners of slaves, who were being compensated for the loss of their “property.”[17] According to the Legacies of British Slave-Ownership at the University College London, Rothschild himself was a successful claimant under the scheme, as part of “Antigua 390 (Mathews or Constitution Hill),” where he was a beneficiary as mortgage holder to a plantation in Antigua which had 158 slaves in his ownership, he received a £2,571 payment at the time (worth £246 thousand in 2020.[18]

Democratic Review

Year of Revolutions of 1848 were celebrated by Americans with frequent parades and proclamations, and foreign revolutionaries like Louis Kossuth emerged as national celebrities. At the highest levels of government, the United States offered diplomatic support.[19] After 1848, a faction of Democrats, concerned about the nation’s failure to support “democratic” revolutions abroad, formed a group identified as Young America.[20] They intended to contrast themselves from the caution of their party’s so-called Old Fogies. Young America argued that the nation could only secure its ideals through more forceful “expansion and progress.” Stephen A. Douglas (1813 – 1861), the U.S. senator from Illinois who would run against Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election, became the leading political figure for citizens who wished to make America a more effective beacon of revolution overseas. Douglas, however, failed to win the Democratic Party nomination for the presidency in 1852.

Young America was founded in 1845 by Edwin De Leone (1818 – 1891), who was born in Columbia, South Carolina of Sephardic Jewish parents, and later became a confidant of Jefferson Davis (1808 – 1889), a Freemason and the first and only President of the Confederacy. In their heyday in the 1840s and 1850s, argues Yonatan Eyal, Young America were led by Stephen Douglas, August Belmont, James Knox Polk (1795 – 1849), and Franklin Pierce (1804 – 1869).[21] The Young America movement also inspired writers such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman. Hawthorne wrote the glowing biography The Life of Franklin Pierce in support of Pierce’s 1852 presidential campaign, which was positively reviewed in the Democratic Review.

Pierce was elected to the White House in 1853 after making numerous appeals to Young America sentiment. From Britain Kossuth went to the United States of America. Kossuth completed a tour of several Masonic lodges to educate the Masonic hierarchy on how to recruit, organize, and train the youth in revolutionary strategy.[22] In the same year, Kossuth made contact with Franklin Pierce (1804 – 1869), offering him the propaganda services of Young America to promote his bid for the presidency in return for appoint particular individuals to important posts. Earlier in the year, the New York Herald reported that Pierce was a “discreet representative of Young America.”[23] Mazzini confirmed in his diary that Pierce was willing to accept help from Kossuth and his network of Masonic operatives: “Kossuth and I are working with the very numerous Germanic element [Young America] in the United States for his [Pierce’s] election, and under certain conditions which he has accepted.”[24] Pierce appointed several Young Americans to the foreign service: George N. Sanders (1812 – 1873) as Consul to London; Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804 – 1864) as Consul to Liverpool; James Buchanan (1791 – 1868) as Minister to the Court of St. James, Great Britain; Pierre Soulé (1801 – 1870) as Minister to Spain; John L. Sullivan as Minister to Portugal; and Edwin De Leone (1818 – 1891) as Consul to Egypt. Mazzini wrote, almost all of Pierce’s nominations “are such as we desired.”[25]

Belmont, a lifelong member of the Democratic Party, had been taken under the wing of his wife’s uncle, John Slidell (1793 – 1871), a staunch defender of slavery as a Representative and Senator, who made Belmont his protégé and encouraged Belmont to enter politics.[26] Belmont lent financial and political support to Pierce’s campaign, resulting in sustained attack from the city’s Whig newspapers, which accused him of using “Jew gold” from abroad to buy votes and maintaining “dual allegiance” to the Habsburg and Rothschild families. In a journalistic war of words that became known in New York City as the “Belmont affair,” Belmont demanded a retraction of a Tribune story, but after he was rebuffed by Horace Greeley, he enlisted the Democratic Herald and Evening Post in his defense.[27] Pierce won the 1852 election easily and appointed Buchanan and Belmont to diplomatic posts in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, respectively. In 1853, Pierce appointed Belmont Chargé d’affaires to The Hague.

Pierce’s first appointment was Freemason Caleb Cushing (1800 – 1879), who as US attorney general became the master-architect of the Civil War. Cushing’s first Masonic assignment was to transfer money from British Masonic banker George Peabody to the Young America abolitionists, who after the elections were calling for the dissolution of the Union.[28] Peabody, who owned a giant banking firm in England, hired the services of J.P. Morgan, Sr. (1837-1913) to handle the funds as they arrived in the United States. Upon Peabody’s death, Morgan took over the firm and later moved it from England to the United States, renaming it Northern Securities. In 1869, Morgan went to London and reached an agreement to act as an agent for the N.M. Rothschild Company in the United States.

The handler of the Peabody funds in London was George N. Sanders, a founder of Young America and a close friend of Mazzini. At his home in London on February 21, 1854, Saunders hosted a dinner party with guests of honor being Mazzini, Blanqui, Kossuth and Carbonari member Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin, and founder of La Réforme. Sanders admitted in conversation that he was a friend of Blanqui, who had worked with Buonarroti, and a member of society at Paris called the “Club Blanqui.”[29] Also in attendance were General Giuseppe Garibaldi; Felice Orsini, one of Mazzini’s henchmen who would attempt to assassinate Napoleon III in 1858; and Alexander Herzen, the “father of Russian Socialism,” who initiated Freemason Mikhail Bakunin into Mazzini’s Young Russia; and Arnold Ruge (1802 – 1880), who with Karl Marx was the editor of a revolutionary magazine for Young Germany.[30] George Sanders gave the toast: “To do away with the Crowned Heads of Europe.”[31]

Also present at Sanders’ meeting in London in 1954 was President Pierce’s US Ambassador to England, Freemason James Buchanan, who would soon become the next president of the United States. With the support of Sanders, Buchanan was nominated in 1856 as president for the Democratic Party. Buchanan, who strongly favored the maintenance of slavery, is consistently ranked by historians as one of the least effective presidents in history, for his failure to mitigate the national disunity that led to the American Civil War. In his famous “House Divided” speech of June 1858, Abraham Lincoln charged that Douglas, Buchanan, his predecessor Pierce, and Chief Justice Roger B. Taney were all part of a plot to nationalize slavery, as allegedly proven by the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857, a landmark decision in which the Supreme Court held that the US Constitution was not meant to include American citizenship for black people, regardless of whether they were enslaved or free, and so the rights and privileges of the Constitution could not apply to them[32]

Standing out among the leaders of the Forty-Eighters was Civil War General Carl Schurz, who has been described by some historians as the most influential U.S. citizen of German birth.[33] It was also in London that Schurz met his Jewish wife, Margarethe Meyer-Schurz, who then moved together to the United States, where she used the training she gained in Germany under Friedrich Fröbel to create the first kindergarten in the United States. After briefly serving as ambassador to Spain, Schurz became a general in the American Civil War, fighting at Gettysburg and other major battles. He was instrumental in helping Abraham Lincoln gain the presidency and also in helping abolish slavery. In the Illinois campaign of 1858 between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, he took part as a speaker on behalf of Lincoln—mostly in German—which raised Lincoln’s popularity among German-American voters.

Douglas’ 1860 presidential campaign was supported by his friend Benjamin Franklin Peixotto (1834 – 1890), who was the American head of the B’nai B’rith and an ally of the Alliance Israëlite Universelle.[34] As a delegate to the pivotal 1860 Democratic National Convention in Charleston, South Carolina, Belmont supported Douglas, who had triumphed in the famous 1858 Lincoln-Douglas Debates over his long-time political rival, the newly recruited Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln, in their battle for Douglas’ Senate seat. Douglas subsequently nominated Belmont as chairman of the Democratic National Committee. Belmont also used his influence with European business and political leaders to support the Union cause in the Civil War, trying to dissuade the Rothschilds and other French bankers from lending funds or credit for military purchases to the Confederacy and meeting personally in London with the British prime minister, Lord Palmerston, and members of Emperor Napoleon III’s French Imperial Government in Paris.[35]

Transcendentalism

The Democratic Review also published some of the early work of Walt Whitman, James Russell Lowell, and Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau (1817 – 1862). American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne married John O’Sullivan’s goddaughter, Sophia Amelia Peabody. Hawthorne was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, where his ancestors included John Hathorne, the only judge involved in the Salem witch trials who never repented of his actions. Much of Hawthorne’s fiction, such as The Scarlet Letter is set in seventeenth-century Salem. In 1851, Hawthorne published The House of the Seven Gables, a Gothic novel whose setting was inspired by the Turner-Ingersoll Mansion, a gabled house in Salem, belonging to Hawthorne’s cousin Susanna Ingersoll, and by his ancestors who had played a part in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. In Young Goodman Brown, the main character is led through a forest at night by the Devil, appearing as man who carries a black serpent-shaped staff. Goodman is led to a coven where the townspeople of Salem are assembled, including those who had a reputation for Christian piety, in-mixed with criminals and others of lesser reputations, as well as Indian priests. Herman Melville said the novel was “as deep as Dante” and Henry James called it a “magnificent little romance.”[36]

Edgar Allan Poe, a fellow contributor to the Democratic Review, referred to Hawthorne’s short stories as “the products of a truly imaginative intellect.”[37] Poe’s gothic works are replete with occult symbolism. Poe’s Cask of Amontillado enacts a Masonic ritual in a way that would be evident only to Masons. The story is set in an unnamed Italian city, told from the perspective of a man named Montresor plots to murder his friend Fortunato during Carnevale (Mardi Gras), while the man is drunk and wearing a jester’s motley. who, he believes, has insulted him. According to Robert Con Davis-Undiano, “the plot of story, from Montresor’s initial meeting with Fortunato during Italian Carnevale, through Fortunato’s final entombment, itself enacts an initiation rite for Freemasonry.”[38]

Hawthorne and Sophia were close friends of a fellow-contributor to the Democratic Review, Sarah Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1810 – 1850) an American journalist and women’s rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movement. Fuller was also influenced by the work of Swedenborg.[39] Margaret Fuller actually fought in the Italian revolution alongside her lover, Giovanni Ossoli, who was a friend of Mazzini.[40] Thomas Carlyle and his wife, Jane, had introduced her to Mazzini.[41] Fuller had met Mazzini in London where she began a friendship and correspondence with him, regarding him as “not only one of the heroic, the courageous, and the faithful,” she wrote, “but also one of the wise.”[42] In 1847, Fuller befriended crypto-Frankist Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz.[43] Fuller’s brother, Arthur Buckminster Fuller (1822 – 1862), was the grandfather of American architect Buckminster Fuller (1895 – 1983).

Fuller consciously adopted Madame Germaine de Staël as her role model.[44] Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick and a contributor to the Democratic Review, considered de Staël among the greatest women of the century.[45] Madame de Staël was frequently quoted by Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1882), and she is credited with introducing him to recent German thought.[46] Influenced by Swedenborg, Blake and the Vedanta, Emerson was the father of American Transcendentalism.[47] Emerson is also well known as a mentor and friend of fellow Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau (1817 – 1862). In addition to Emerson, Fuller was also an inspiration to Whitman, considered one of America’s most influential poets. Whitman’s work was very controversial even in its time, particularly his poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its overt sexuality. Though biographers continue to debate his sexuality, he is usually described as either homosexual or bisexual in his feelings and attractions. Oscar Wilde met Whitman in America in 1882 and wrote that there was “no doubt” about Whitman’s sexual orientation: “I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips,” he boasted.[48]

The Transcendental Club also included Elizabeth Palmer Peabody (1804 –1894), the sister of Hawthorne’s wife Sophia, a member of one of the upper-class families known as the Boston Brahmins. Elizabeth opened Elizabeth Palmer Peabodys West Street Bookstore, at her home in Boston, where Fuller would hold her “conversations,” and published books from Nathaniel Hawthorne and others in addition to the periodicals The Dial and Æsthetic Papers. Emerson was so impressed with Fuller that he invited her to join the Transcendental Club and to edit its literary review, The Dial. Elizabeth had a particular interest in the educational methods of Friedrich Fröbel, particularly after meeting one of his students, Carl Schurz’s Jewish wife Margarethe, in 1859.[49] She visited Germany in 1867 to study Fröbel’s teachings more closely. In 1868, Elizabeth invited Maria Kraus Boelte (1836 – 1918) to come to Boston, but she refused. She later founded with her husband the New York Seminary for Kindergartners.[50]

Elizabeth was also the first known translator into English of the Buddhist scripture the Lotus Sutra, translating a chapter from its French translation in 1844. She also became a writer and a prominent figure in the Transcendental movement. Elizabeth and Sophia’s sister Mary Tyler was the wife of Horace Mann (1796 – 1859), who served as Secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education, Mann was elected to the United States House of Representatives. Elizabeth Peabody and Carl Schurz were buried in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, the burial ground of numerous famous figures, including Washington Irving, whose 1820 short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” is set in the adjacent burying ground at the Old Dutch Church of Sleepy Hollow.

Mystick Krewe of Comus

Mimi L. Eustis published a website in 2005, titled Mardi Gras Secrets, to share the deathbed confessions of her father Samuel Todd Churchill, a high-level member of the Mystick Krewe of Comus, a secret society founded in 1856 by Judah P. Benjamin—whose mentor was Slidell—and Albert Pike in order to meet and communicate the plans of the Rothschilds. The Mystick Krewe of Comus, which is named after John Milton’s Lord of Misrule in his masque Comus, is oldest continuous organization of New Orleans Mardi Gras, a modern adaptation of the Feast of Fools festival. Prior to the advent of Comus, Carnival celebrations in New Orleans were mostly confined to the Roman Catholic Creole community, and parades were irregular and often very informally organized. The inspiration for the Krewe of Comus came from Rosicrucian author John Milton’s Lord of Misrule in his masque Comus. The rebellious Thomas Morton (c. 1579 – 1647), who had maintained contacts with the School of Night, declared himself “Lord of Misrule” during the pagan revelry in Merrymount in 1627, and his fellow celebrants were described Nathaniel Hawthorne in The May-Pole of Merry Mount (1837) as a “crew of Comus.”

Cushing, recounted Eustis, dispatched Pike to Arkansas and Louisiana. Pike’s mission was to further the cause of slavery and to foment an America civil war, and to establish a line of communication with other fellow Illuminati. Pike was chosen by Cushing to head an Illuminati branch in New Orleans and to establish a New World order. Pike moved his law office to New Orleans in 1853 and was made Masonic Special Deputy of the Supreme Council of Louisiana on April 25, 1857. Eustis further asserts, Pike and Judah P. Benjamin needed a secret society in order to foster a civil war in the United States and to establish the House of Rothschild, for which purpose they founded the Mystick Krewe of Comus.

Pike headed the Southern Jurisdiction, while Cushing was connected to the Northern Jurisdiction of Freemasonry. The Northern Jurisdiction was still under the British spy and 33rd-degree Freemason John J.J. Gourgas (1777 – 1865), who helped found the KGC.[51] The English Masons sent Gourgas to New York to organize clandestine Scottish Rite lodges that would appear to be pro-French but would in fact were pro-English to help Britain in the War of 1812. In the summer of 1813, Emanual de la Motta, one of the founders of the Supreme Council of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite in Charleston, and a congregant of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, reached a territorial agreement with Gourgas whereby the northern area was under the English Northern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry and based in Boston, while Charleston became the base for the French Southern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry.[52]

According to Eustis, both Pike and Benjamin were secret Kings of the Mystic Krewe of Comus, and participated directly in the killing of President Abraham Lincoln. Although officially, the Krewe of Comus claims to descend from the Cowbellion de Rakin Society of Mobile, Alabama, Eustis’ father claimed the society was founded by Yankee bankers from New England, who used the society as a front for the House of Rothschild, as well as for Skull and Bones, which was a branch of the Bavarian Illuminati. Passage into the secret of the code number 33, the highest stages of membership within the Skull and Bones society, required participation in the ritual “Killing of the King.” Eustis says her father emphasized that most Masons below the 3º remained in ignorance, while those to who rose past the 33º did so by participating in the “Killing of the King” ritual.

Knights of the Golden Circle

Pike headed the Southern Jurisdiction, while Cushing was connected to the Northern Jurisdiction of Freemasonry. The Northern Jurisdiction was still under the British spy and 33rd-degree Freemason John J.J. Gourgas (1777 – 1865), who helped found the KGC.[53] The English Masons sent Gourgas to New York to organize clandestine Scottish Rite lodges that would appear to be pro-French but would in fact were pro-English to help Britain in the War of 1812. In the summer of 1813, Emanual de la Motta, one of the founders of the Supreme Council of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite in Charleston, and a congregant of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, reached a territorial agreement with Gourgas whereby the northern area was under the English Northern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry and based in Boston, while Charleston became the base for the French Southern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry.[54]

In 1854, Gourgas is said to have helped found a secret society known as the Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC), from which emerged the Ku Klux Klan.[55] The KGC, which included Albert Pike, Jefferson Davis and John Wilkes Booth (1838 – 1865) became the first and most powerful ally of the newly-created Confederate States of America, commonly referred to as the Confederacy and the South.[56] A testament to the power of the KGC and their conflict with Lincoln was revealed during the Civil War in The Private Journal and Diary of John H. Surratt, The Conspirator, written in 1866. In this journal, Surratt details how he was inducted to the KGC in 1860 by fellow Knight, John Wilkes Booth, a well-known actor and outspoken Confederate sympathizer, at a “castle” in Baltimore, Maryland. Surratt describes the elaborate rituals of the ceremony and of cabinet members, congressmen, judges, actors, and other politicians who were in attendance. Surratt details Booth meeting in Montreal where he agreed to kill Lincoln. Booth apparently received approval for the plot from Benjamin, through the KGC.[57] The KGC and their conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln formed part of the plot of a 2007 film, National Treasure: Book of Secrets, starring Nicolas Cage.

In Lincoln and the Jews, historians Jonathan D. Sarna and Benjamin Shapell explore the possibility that Booth belonged to a family of Spanish Jewish ancestry. Booth’s sister, Asia Booth Clarke, stated in her 1882 memoir that their father, Junius Brutus Booth, attended synagogues along with other houses of worship: “In the synagogue, he was known as a Jew, because he conversed with rabbis and learned doctors, and joined their worship in the Hebraic tongue. He read the Talmud, also, and strictly adhered to many of its laws.”[58]

Killing of the King

In 1864, an editorial for the Chicago Tribune spoke of the Rothschilds, their “Jewish” agent August Belmont, “and the whole tribe of Jews,” who reportedly sympathized with the South.[59] The New York Times noted that “the great Democratic Party has fallen so low that it has to seek leaders in the agent of foreign Jew bankers.”[60] The Rothschilds asked the American consul in Frankfurt to inform the State Department that neither Baron Rothschild nor members of his family were supporting the Confederacy. The most publicized anti-Semitic incident occurred after General Ulysses S. Grant issued General Order No. 11 that expelled all Jews from his military district in western Tennessee on December 17, 1862. The fact remains, however, that many Jews during the period sympathized with the South and found employment as blockade runners and black-market profiteers. Isaac Leseer (1806 – 1868), the leader of Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, commented in the Occident that, “It has been the fashion to call all who were engaged in smuggling or blockade running, as it was termed, Jews.”[61]

Most often serving as their attorney was another Forty-Eighter, Peixotto’s friend and collaborator, Simon Wolf (1836 – 1923), the head of the B’nai B’rith for Washington DC, and also a friend of John Wilkes Booth.[62] Originally from Bavaria, Wolf emigrated to Ohio with his grandparents when he was twelve years old amidst the upheaval of the failed Revolutions of 1848. He would eventually make friends with presidents Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, William McKinley and Woodrow Wilson. Among his friends was also Edwin McMasters Stanton (1814 – 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War, who would later organize the manhunt for Booth. Prior to that, Lafayette C. Baker (1826 – 1868), the chief of the War Department’s Detective Bureau, arrested Wolf because he suspected him of working as an enemy agent and because of his leadership in B’nai B’rith, which Baker considered, “a disloyal organization which has its ramifications in the South, and… helping traitors.”[63] However, Stanton lashed out at Baker. Baker owed his appointment largely to Stanton, but suspected the secretary of corruption and was eventually demoted for tapping his telegraph lines and transferred out to New York.

Wolf was meant to be at Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, but was not able to attend, due to an illness in the family. Back when Wolf lived in Cleveland, was a stronghold for the Knights of the Golden Circle, he’d been involved in theatrical productions with both Peixotto and Booth.[64] More remarkably, Wolf spent that afternoon Booth. According to Wolf, Booth invited him for drinks at the Metropolitan Hotel in Washington. He had just been rejected by a senator’s daughter for the third time and needed to be consoled. “I knew Booth well,” writes Wolf. “We had played on the amateur stage together in Cleveland, Ohio, and I had met him that very morning in front of the Metropolitan Hotel. He asked me to take a drink. He seemed very excited, and rather than decline and incur his enmity I went with him. It was the last time I ever saw Booth.”[65]

Working in Montreal for the operation to assassinate Lincoln was Sanders. Jefferson Davis had named Sanders as his Representative as an ex-officio member of the Confederate Micheners in Canada late in the Civil War.[66] In 1864, a stranger who appeared to be a well-dressed Italian spoke with a Mr. Boteler, a member of Congress from Virginia, who claimed to have been sent on a mission to Richmond. He admitted:

I belong to the society of the Carbonari! It sympathizes with the Southern Confederacy; and it is the only power in Europe that can compel its recognition, for Napoleon III is secretly a member of the society, and dares not disobey its mandates. More than this, I hold in may hand the life of Abraham Lincoln; the victim who the Carbonari designate cannot elude them.[67]

Finally, on May 2, 1865, President Johnson issued a $25,000 reward for Sanders’ arrest in connection with Lincoln’s assassination. The charges were ultimately dropped, but Sanders had probably encouraged John Wilkes Booth, although he was ultimately able to absolve the Confederacy of any blame in the plot.[68] He had also made several trips to Europe to further the cause of the Southern States. Sanders fled to Canada and Europe. He later returned to the United States soon before he died in 1873 in New York. In Murdering Mr. Lincoln, Charles Higham asserts that Sanders was the driving force behind the assassination. Higham alleges that in June 1864, Sanders plotting against Lincoln with the Confederate Secret Service in Montreal. Higham asserts that when Booth arrived in Montreal in October of that year, he fell under the influence of Sanders and arranged Lincoln’s assassination there.

Lafayette C. Baker was recalled to Washington after the assassination. Within days, Booth was arrested and along with David Herold was eventually shot and killed. The following year, Baker was fired when President Johnson accused him of spying on him, a charge Baker later admitted in his book which he published in response. He also announced that he had had Booth’s diary in his possession which was being suppressed by Stanton. When the diary was eventually produced, Baker claimed that eighteen essential pages were missing. It was suggested by Otto Eisenschiml in his book, Why Was Lincoln Murdered?, that these would implicate Stanton in the assassination.[69]

Ku Klux Klan

During the Civil War, Judah P. Benjamin served as Secretary of War under Jefferson Davis, until the fall of the Confederacy on May 26, 1865. To evade certain imprisonment and possible execution, Benjamin escaped from the fallen Confederate capital at Richmond. Benjamin’s goal was to go as far away from the United States as he could—if need be, to “the middle of China,” he told friends. After his escape to England, he became an English barrister.[70] In 1872, he attained the rank of Queen’s Counsel, and came to be recognized as the unquestioned leader of the British bar. A farewell dinner was given in Benjamin’s honor by the bench and bar of England in the hall of the Inner Temple, London, in 1883, under the presidency of the attorney-general, Sir Henry James.[71]

When he received a visit in London in 1867 from Bishop Richard Hooker Wilmer (1816 – 1900), who told him of the power the Ku Klux Klan—which had been founded on December 24, 1865—fwas exerting in the United States, and for the need to control the negroes, Benjamin was moved to provide funding for its activities.[72] According Susan L. Davis in Authentic History of the Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1877, Albert Pike was the “chief judicial officer” of the Klan.[73] According to As reported by Davis, Pike organized the Klan in Arkansas after Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821 – 1877), a CSA general in the Civil War, a Freemason and the first Grand Wizard of the Klan, appointed him Grand Dragon of that Realm.[74] Prior to assembling the first convention of the KKK in 1867, as the organization was growing, it was decided that General Robert E. Lee should serve as their national leader. Six men were chosen to present Lee the offer, including Wilmer as well as Major Felix G. Buchanan, of Lincoln County; Captain John B. Kennedy of the Pulaski Ku Klux Klan, Captain William Richardson of the Athens KKK, and Captain John B. Floyd, of the Alabama KKK.[75]

Wilmer was a close friend of General John Tyler Morgan (1824 – 1907), the Second Dragon of the Realm of Alabama.[76] Morgan was a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, a six-term U.S. senator from the state of Alabama after the war. An ardent racist and ex-slave holder, he was a proponent of Jim Crow laws, states rights and racial segregation through the Reconstruction era. He “introduced and championed several bills to legalize the practice of racist vigilante murder [lynching] as a means of preserving white power in the Deep South.”[77] Morgan was an important ally of General Henry Shelton Sanford (1823 – 1891), a wealthy American businessman and aristocrat from Connecticut who served as United States Minister to Belgium from 1861 to 1869. Sanford coordinated northern secret service operations during the Civil War, arranged for the purchase of war materials for the Union, and delivered a message from Secretary of State William H. Steward to Giuseppe Garibaldi, offering him a Union command.

Congo Free State

In 1876, Sanford was named acting Delegate of the American Geographical Society to a conference called by King Leopold II of Belgium (1835 – 1909) to organize the International African Association (IAA) with the purpose of opening up equatorial Africa to “civilizing” influences. Leopold was the second child of the reigning Belgian monarch, Leopold I of Belgium (1790 – 1865), and of his second wife, Louise, the daughter of King Louis Philippe of France (1773 – 1850), the son of Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (Philippe Égalité). Leopold I was the youngest son of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1750 – 1806), of the Saxe-Coburg-Gotha family who gained prominence in the nineteenth century through financial links with the Rothschilds.[78] Leopold I’s grandfather was Ernst II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, who granted refuge to his friend the fugitive Illuminati founder Adam Weishaupt.[79] It was Leopold I who promoted the marriage of Ernst II’s grandson Prince Albert to his niece, Queen Victoria.

The IAA was supported by the Rothschilds and Viscount Ferdinand de Lesseps, a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal.[80] The Association was used by King Leopold ostensibly to further his altruistic and humanitarian projects in the area of Central Africa, the area that was to become Leopold’s privately controlled Congo Free State. Sanford was a longtime supporter of the Republican Party to which President Chester A. Arthur (1829 – 1886) belonged, and Leopold believed that he could use Sanford to convince Arthur to formally recognize his claims to Congolese land. Sanford convinced Morgan that, by recognizing the existence of Leopold II’s Congo landholdings, the U.S. would have a way to establish economic connections between itself and Africa, perhaps opening up a new market for Alabama’s cotton surplus. Morgan introduced a Senate resolution recognizing Leopold’s Congo claims, and in April 1884, the U.S. became the first country to officially recognize King Leopold II’s claim to the Congo. U.S. recognition of the Congo immediately strengthened Leopold’s position in Africa.

Viscount de Lesseps declared Leopold’s plans “the greatest humanitarian work of this time.”[81] However, Adam Hochschild’s best-seller King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, detailed the atrocities that took place in Leopold’s pillage of the Congo. At first, ivory was exported, but when the global demand for rubber exploded, attention shifted to the labor-intensive collection of sap from rubber plants. Leopold used slave-labor—coerced through torture, imprisonment, maiming and terror—to strip the county of vast amounts of wealth, largely in the form of ivory and rubber. Murder was common, and rape and sexual exploitation were rampant. Modern estimates range from one million to fifteen million Congolese people died under his regime, with a consensus growing around ten million.[82] Leopold’s Congo inspired Joseph Conrad when he wrote Heart of Darkness (1899), which was also later the basis for Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film Apocalypse Now.

[1] William Earl Weeks. Building the continental empire: American expansion from the Revolution to the Civil War (Ivan R. Dee, 1996), p. 61.

[2] Justin B. Litke. “Varieties of American Exceptionalism: Why John Winthrop Is No Imperialist,” Journal of Church and State, 54 (Spring 2012), pp. 197–213.

[3] “Free Sons of Israel.” New York Times (April 7, 1895). Retrieved from https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1895/04/07/102510715.pdf

[4] “Jewish Orders.” Freimaurer-Wiki. Retrived from https://www.freimaurer-wiki.de/index.php/En:Jewish_Orders#Free_Sons_of_Israel

[5] Daniel Soyer. “Entering the ‘Tent of Abraham’: Fraternal Ritual and American-Jewish Identity, 1880-1920.” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, 9, no. 2 (1999), p. 166.

[6] John Daniel. Scarlet and the Beast: A History of the War Between English and French Freemasonry, Vol. 3 (John Kregel, Inc., 1994).

[7] Hagger. The Secret Founding of America.

[8] Susan Lawrence Davis. Authentic History of the Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1877 (New York: Susan Lawrence Davis, 1924).

[9] Irving Katz. August Belmont; a political biography (New York/London: Columbia University Press, 1968).

[10] Ibid., Kindle Locations 3133-3139

[11] Adler & Kohler. “Benjamin, Judah Philip.”

[12] Maury Wiseman. “Judah P. Benjamin and slavery.” American Jewish Archives Journal 59,1-2 (2007): 107-114.

[13] “Ham’s curse, blackness and sin.” University of Capetown News (March 29, 2004).

[14] Michael W. Homer. “‘Why then introduce them into our inner temple?’: The Masonic Influence on Mormon Denial of Priesthood Ordination to African American Men.” The John Whitmer Historical Association Journal, Vol. 26 (2006), pp. 238.

[15] Carola Hoyos. “Rothschild and Freshfields founders linked to slavery.” Financial Times (June 26, 2009).

[16] Kris Manjapra. “When will Britain face up to its crimes against humanity?” The Guardian (March 29, 2018).

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Nathan Mayer Rothschild.” Legacies of British Slave-ownership (University College London). Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146631430

[19] “Revolution - 1848 and ‘young america’” Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy. Retrieved from https://www.americanforeignrelations.com/O-W/Revolution-1848-and-young-america.html

[20] Ibid.

[21] Yonatan Eyal. The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, 1828–1861 (2007)

[22] Daniel. Scarlet and the Beast.

[23] Merle E. Curti, “Young America.” American Historical Review (October 1926), p. 44.

[24] As cited in Daniel. Scarlet and the Beast.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Irving Katz. August Belmont: a political biography (New York/London: Columbia University Press, 1968).

[27] Ibid., pp. 10–21.

[28] As cited in Daniel. Scarlet and the Beast.

[29] Sigmund Diamond, ed. A Casual View of America—The Home Letters of Solomon de Rothschild (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1961), p. 22.

[30] Ibid.; Mark A. Lause. A Secret Society History of the Civil War (University of Illinois Press, 2011), p. 1.

[31] Michael Walzer “On Democratic Internationalism.” Dissent (Spring 2016). Retrieved from https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/democratic-internationalism-hungarian-revolution-irving-howe

[32] John Burt. Lincoln’s Tragic Pragmatism: Lincoln, Douglas, and Moral Conflict (Harvard University Press, 2013). p. 95.

[33] Charlotte L. Brancaforte (ed.) The German Forty-Eighters in the United States (New York: Lang, 1989). Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/forty-eighters

[34] Cyrus Adler, E. A. Cardozo. “Peixotto.” Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/11993-peixotto; Benjamin Peixotto. “Principality, now Kingdom, of Roumania.” Menorah, I: 1 (July, 1886), p. 212.

[35] Allen Johnson (ed.) Dictionary of American Biography, Vol. II (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1929), pg. 170.

[36] Edwin Haviland Miller. Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991), p. 119.

[37] Arthur Hobson Quinn. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), p. 334.

[38] Robert Con Davis-Undiano. “Poe and the American Affiliation with Freemasonry.” symplokē, Vol. 7, No. 1/2, Affiliation (1999), p. 125.

[39] Philip F. Gura. American Transcendentalism: A History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007), p. 172.

[40] Michael Walzer “On Democratic Internationalism.” Dissent (Spring 2016). Retrieved from https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/democratic-internationalism-hungarian-revolution-irving-howe

[41] Judith Thurman. “The Desires of Margaret Fuller.” The New Yorker (March 25, 2013).

[42] David M. Robinson. “Margaret Fuller and the coming democracy.” OUPblog (August 21st 2017). Retrieved from https://blog.oup.com/2017/08/margaret-fuller-democracy/

[43] Kazimierz Wyka. “Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard.” Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 703.

[44] Joel Porte. In Respect to Egotism: Studies in American Romantic Writing (Cambridge University Press, 1991), p. 23.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Sarah M. Pike. New Age and Neopagan Religions in America, Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

[48] Neil McKenna. The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde. (Century, 2003) p. 33.

[49] “Kindergartens: A History (1886).” Social Welfare History Project (July 15, 2015). Retrieved from https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/education/kindergartens-a-history-1886/

[50] Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, Paul S. Boye & Radcliffe College. Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary (Harvard University Press, 1971).

[51] Daniel. Scarlet and the Beast.

[52] Hagger. The Secret Founding of America.

[53] Daniel. Scarlet and the Beast.

[54] Hagger. The Secret Founding of America.

[55] Daniel. Scarlet and the Beast.

[56] Fred Milliken. “Freemasonry’s Connection With The Knights Of The Golden Circle.” Freemason Information (December 29, 2012). Retrieved from http://freemasoninformation.com/2012/12/freemasonry-and-the-knights-of-the-golden-circle/

[57] The Great Conspiracy, A Book of Absorbing Interest! Startling Developments… and the Life and Extraordinary Adventures of John H. Surratt, the Conspirator (Philadelphia: Barclay, 1966), pp. 36-37, 70, 111-13.

[58] Lenny Picker. “Was John Wilkes Booth Jewish?” Forward (April 3, 2015). Retrieved from https://forward.com/culture/217871/was-john-wilkes-booth-jewish/

[59] Leonard Dinnerstein. Antisemitism in America (Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 31.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid., p. 32.

[62] Steven Hager. “Is Simon Wolf a key to the Lincoln assassination?” The Tin Whistle (September 23, 2014). Retrieved from https://stevenhager.net/2014/09/23/is-simon-wolf-a-key-to-the-lincoln-assassination/

[63] Ibid.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ellis Washington. “Myths vs. Facts (Part 8) – Young America: Illuminati Influence on Education.” (June 14, 2019).

[67] Edward Pollard. Life of Jefferson Davis With a Secret History of the Southern Confederacy (1869), p. 412.

[68] Melinda Squires. “The Controversial Career of George Nicholas Sanders.” Masters Thesis (Western Kentucky University, 2000).

[69] Edward Steers Jr.. Lincoln Legends (University Press of Kentucky, 2007), pp. 177-202.

[70] William C. Davis. An Honorable Defeat: The Last Days of the Confederacy Government (New York: The Free Press, 2001), pp. 244–245.

[71] Adler & Kohler. “Benjamin, Judah Philip.”

[72] Susan Lawrence Davis. Authentic History of the Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1877 (New York: Susan Lawrence Davis, 1924), p. 46.

[73] “Albert Pike did not found the Ku Klux Klan.” Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon (http://freemasonry.bcy.ca accessed January 18, 2018).

[74] Susan Lawrence Davis. Authentic History of the Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1877 (New York: Susan Lawrence Davis, 1924); William R. Denslow. 10,000 Famous Freemasons (Columbia, Missouri, USA: Missouri Lodge of Research, 1957). (digital document by phoenixmasonry: vol. 1, 2, 3, 4).

[75] Davis. Authentic History, Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1877, p. 102.

[76] Ibid., p. 45.

[77] David Holthouse. “Activists Confront Hate in Selma, Ala.” Intelligence Report (Winter 2008).

[78] Ferguson. The House of Rothschild, p. 157.

[79] Stauffer. New England and the Bavarian Illuminati.

[80] Adam Hochschild. King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Mariner Books,1999) p. 46.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Asafa Jalata. “Colonial Terrorism, Global Capitalism and African Underdevelopment: 500 Years of Crimes Against African Peoples.” Journal of Pan African Studies, 5, 9 (March 2013).

Zionism

Introduction

Kings of Jerusalem

The Knight Swan

The Rose of Sharon

The Renaissance & Reformation

The Mason Word

Alchemical Wedding

The Invisible College

The New Atlantis

The Zoharists

The Illuminati

The American Revolution

The Asiatic Brethren

Neoclassicism

Weimar Classicism

The Aryan Myth

Dark Romanticism

The Salonnières

Haskalah

The Carbonari

The Vormärz

Young America

Reform Judaism

Grand Opera

Gesamtkunstwerk

The Bayreuther Kreis

Anti-Semitism

Theosophy

Secret Germany

The Society of Zion

Self-Hatred

Zionism

Jack the Ripper

The Protocols of Zion

The Promised Land

The League of Nations

Weimar Republic

Aryan Christ

The Führer

Kulturstaat

Modernism

The Conservative Revolution

The Forte Kreis

The Frankfurt School

The Brotherhood of Death

Degenerate Art

The Final Solution

Vichy France

European Union

Eretz Israel