32. Jack the Ripper

Dracula

Eerily, Adolf Hitler was born on April 20, 1889, almost exactly nine months after the gruesome murders of by Jack the Ripper, which involved a network connected to the Golden Dawn and the founders of the Round Table, an organization that would be central in helping to bring about the Balfour Declaration of 1917. The Jack the Ripper murders served as inspiration to the novel Dracula, by Golden Dawn member Bram Stoker, whose consultant on Transylvanian culture was a close friend of Theodor Herzl, Hungarian Zionist named Arminius Vambery (1832 – 1913), an agent of Lord Palmerston. Dracula was inspired by the vampire novel Carmilla by Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu (1814 – 1873), an Irish writer of Gothic tales and mystery novels inspired by Swedenborg. According to one occult historian, the model for le Fanu’s Carmilla was Barbara of Cilli, who assisted her husband Emperor Sigismund in founding the Order of the Dragon in 1408, was a vampire who was taught by Abraham of Worms, student of Abramelin the Mage.[1] The Book of Abramelin had regained popularity in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries due to the efforts of Golden Dawn founder MacGregor Mathers’ translation, and later within the mystical system of Aleister Crowley’s Thelema.

When Herzl wanted to make contact with British diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes (1853 – 1902), founder of the Round Table, through one of its founding members, William T. Stead (1849 – 1912)—the famous British journalist and friend of Annie Besant and H.P. Blavatsky—he contacted Joseph Cowen (1868 – 1932), a founder and leader of the English Zionist Federation, which would later be the recipient of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, granting the land of Palestine to Jewish settlement, addressed to Walter Rothschild, the son of Baron Nathan Rothschild (1840 – 1915), the head of the London branch of the family bank, N.M. Rothschild & Sons, also a founding member of the Round Table.[2] Nathan, whose father was Baron Lionel de Rothschild, a friend of Benjamin Disraeli, married Emma Louise von Rothschild, the daughter of Mayer Carl von Rothschild who recommended Gerson Bleichröder to Otto von Bismarck as a banker.[3] Nathan’s brother Alfred Rothschild was tutored by Wilhelm Pieper, Karl Marx’s private secretary.[4] Cowen numbered among his friends the entire circle of Carbonari: Mazzini, Garibaldi, Louis Blanc, Bakunin, Ledru-Rollin, Herzen, Orsini, and Kossuth, who met in London at the dinner party of Lincoln-assassination conspirator George N. Sanders in 1854.[5] With Karl Marx, this was largely the same circle of 1848 revolutionaries or Forty-Eighters who participated in the salons of Comtesse Marie d’Agoult, the mother of Richard Wagner’s wife Cosima, who were supporters of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Stead was a British newspaper editor, regarded as a pioneer of investigative journalism. However, Stead was also a central figure in a strange confluence that connected the Jack the Ripper murders with the Golden Dawn and the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF)—who had sponsored the first Masonic lodge in Palestine—as well as H.P. Blavatsky and Papus, the leading disciple of the synarchism of Alexandre Saint-Yves d’Alveydre, who were associated with the Protocols of Zion. More importantly, Stead, with Rhodes and Baron Nathan Rothschild, was also an original founding member of the Round Table, whose plotting for global domination the Protocols purportedly referred to, and yet also was the organization behind the settlement of Jews in Israel.

Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews

Early British political support for an increased Jewish presence in the region of Palestine, based upon geopolitical considerations, began in the early 1840s and was led by Lord Palmerston, following the occupation of Syria and Palestine by separatist Ottoman governor Muhammad Ali of Egypt.[6] While the French exercised an influence in the region as protector of the Catholic communities, Russians of the Eastern Orthodox, Britain without a sphere of influence. These political aspirations were supported by evangelical Christian sympathy for the “restoration of the Jews” to Palestine among elements of the mid-nineteenth-century British political elite, most notably Lord Shaftesbury (1801 – 1885), who married Lady Emily Caroline Catherine Frances Cowper, who was likely to have been the natural daughter of Lord Palmerston.

Shaftesbury was the grandson of Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671 – 1713), was highly esteemed by Moses Mendelssohn,[7] and Yirmiyahu Yovel, author of The Other Within: The Marranos, listed him as an example of “marranesque” philosophy, along with Hobbes, Spinoza, Hume Diderot, Mandeville, Locke, Montaigne, Boyle, Kant and Descartes. Not only Leibniz, Voltaire and Diderot, but Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Moses Mendelssohn, Christoph Martin Wieland and Johann Gottfried von Herder, all drew from his philosophy.[8] Shaftesbury, was one of the first leading Christian Zionists, and an early proponent of the Restoration of the Jews to the Holy Land, providing the first proposal by a major politician to resettle Jews in Palestine. Lord Shaftesbury sought to turn his vision of a restored and converted Israel, including Jewish resettlement in Palestine and the creation of an Anglican church on Mt. Zion, into official government policy. Shaftesbury became president of the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews, founded in 1809 by leading evangelical Anglicans such as Simeon and William Wilberforce, a leader of the Clapham sect, and Charles Simeon (1759 – 1836), who desired to promote Christianity among the Jews. Most early nineteenth-century British Restorationists, like Simeon, were Postmillennial in eschatology, an interpretation of chapter 20 of the Book of Revelation which sees Christ’s second coming as occurring after the Millennium.[9]

The society’s work began among the poor Jewish immigrants in the East End of London and soon spread to Europe, South America, Africa and Palestine.[10] It supported the creation of the post of Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem in 1841, and the first incumbent was one of its workers, Michael Solomon Alexander (1799 – 1845), a former rabbi who converted to Christianity from Judaism.[11] It was Shaftesbury who persuaded Palmerston to appoint James Finn (1806 – 1872), a member of the society, as British consul to Jerusalem in 1838, “to afford protection of the Jews generally” in Palestine.[12]

One of the goals of the London Society was the establishment of an Anglican bishopric in Jerusalem, which was formed when the British and Prussian Governments as well as the Church of England and the Evangelical Church in Prussia entered into a unique agreement. Prussian Union of Churches became the largest independent religious organization in the German Empire and later Weimar Germany. Karl Marx’s father, Heinrich Marx, known as a child as Herschel, converted from Judaism to join the state Evangelical Church of Prussia, taking on the German forename Heinrich over the Yiddish Herschel.[13] In 1816, at the age of seven years, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, the grandson of Moses Mendelssohn, was baptized with his brother and sisters in a home ceremony by Johann Jakob Stegemann, minister of the Evangelical congregation of Berlin’s Jerusalem Church and New Church.[14] Although Mendelssohn was a conforming Christian as a member of the Reformed Church, he was both conscious and proud of his Jewish ancestry and notably of his connection with his grandfather Moses.[15] In 1843, Mendelssohn accepted a leadership position as Generalmusikdirektor at the Belin Cathedral, a central institution of the Prussian Union Church, and he composed numerous pieces of music for use in the service.[16]

The Damascus Incident of 1840 provided a motive for more concrete British intervention on behalf of the Jews in Turkey. Under the influence of Shaftesbury, Lord Palmerston, the Foreign Secretary, called on the Ottoman Empire to facilitate the settlement of Jews from all Europe and Africa in Palestine in addition to allowing Jews living in the Turkish empire “to transmit to the Porte, through British authorities, any complaints which they might have to prefer against the Turkish authorities.” The Sultan made the grant in February 1841, and equality of treatment to Jewish subjects was guaranteed in April. The British government wanted to prop up the ailing Ottomans, and admitting Jews to Palestine with “the wealth they would bring with them would increase the resources of the Sultan’s dominions.”[17]

The bishopric had the support of the Protestant king Frederick William of Prussia: his envoy appointed to England, specifically to aid Shaftesbury y in the project. In 1840, Alexander McCaul (1799 – 1863) was appointed principal of the Hebrew college founded by the London Society. McCaul was for some time tutor to the Earl of Rosse (1800 – 1867), who became president of the Royal Society. McCaul studied Hebrew and German at Warsaw, and at the end of 1822 went to St. Petersburg, where he was received by Alexander I of Russia. Moving to Berlin, he was befriended by George Henry Rose, the English ambassador, and by the Frederick William IV of Prussia, who had known him at Warsaw. In the summer of 1841, through Frederick William IV, he was offered the Protestant Bishopric in Jerusalem, but declined it because he thought it would be better held by one who had been a Jew.[18] Instead, his friend Michael Solomon Alexander was appointed (1799 – 1845), a converted Jew and professor of Hebrew and Arabic at King’s College, was chosen by Palmerston, on the advice of Shaftesbury.

Finn married McCaul’s daughter, Elizabeth Anne Finn (1825 – 1921). In 1849, Elizabeth helped to establish the Jerusalem Literary Society, which attracted the notice of Prince Albert (1819 – 1861), the husband of Queen Victoria, as well as George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen (1784 – 1860) and the Archbishop of Canterbury. She raised funds to purchase a farm outside Jerusalem, which became known as Kerem Avraham, founded in 1855, where the Finns established The Industrial Plantation for Employment of Jews in Jerusalem, to allow the local Jewish population could become self-sufficient. In 1882, Elizabeth launched the Society for Relief of Distressed Jews to provide support for Russian Jews suffering persecution during pogroms. Sir John Simon (1818 – 1897), a leading member of England’s Jewish community was moved to testify to “Mrs Finn’s extraordinary knowledge of his people and astonishment that a Christian should take such an interest in his afflicted people.”[19]

Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF)

Finn continued to lecture on Biblical subjects in the Assyrian Room of the British Museum and retold her experiences in Jerusalem in support for the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) at fundraising meetings to build on the legacy of the Jerusalem Literary Society. In 1875, Shaftesbury told the Annual General Meeting of the PEF, that “We have there a land teeming with fertility and rich in history, but almost without an inhabitant—a country without a people, and look! scattered over the world, a people without a country,” being one of the earliest usages by a prominent politician of the phrase “A land without a people for a people without a land,” which was to become widely used by Zionists as justification for the conquest of Palestine.[20] Along with individuals, a number of institutional members supported the PEF, including the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the Society of Antiquaries, Oxford and Cambridge Universities, the Grand Lodge of Freemasons.[21]

An important member of the PEF was Field Marshal Lord Kitchener (1850 – 1916), who Lanz von Liebenfels claimed was a member of his Order of New Templars (ONT) and a reader of his anti-Semitic magazine Ostara.[22] Nevertheless, Kitchener was also a close friend of Nathan’s brother Rothschild.[23] Kitchener was commissioned into the Royal Engineers in 1871, and in 1874 he was assigned by the PEF to a mapping-survey of the Holy Land. As Chief of Staff in the Second Boer War, Kitchener won notoriety for his imperial campaigns, and later played a central role in the early part of World War I.

Another important member of the PEF was Baron Lionel de Rothschild. Prime Minister Gladstone proposed to Queen Victoria that Lionel be made a British peer. She declined, asserting that titling a Jew would raise antagonism and that it would be unseemly to reward a man whose wealth was based on what she called “a species of gambling” rather than legitimate trade.[24] Lionel shared a friendship with Benjamin Disraeli and Prime Minister Gladstone with Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts (1814 – 1906), the granddaughter of Henry Poole’s banker Thomas Coutts. In 1837, Angela inherited Thomas’ fortune and became the wealthiest woman in England after Queen Victoria. 1839, Angela offered herself in marriage to the much older the Duke of Wellington, who also had a close friendship with Madame de Staël.[25] She befriended Charles Dickens who dedicated Martin Chuzzlewit to her and she was said to be the inspiration for Agnes Wickford in David Copperfield. Together with Dickens she founded a home for “fallen” women known as Urania Cottage, recalling the name later adopted by the Isis-Urania Temple of Golden Dawn.[26] Angela was a friend of Robert Walter Carden, whose son, Alexander James Carden, was initiated into the Isis-Urania temple in London, in March 1891.[27] Together with Arthur Conan Doyle, Henry James and Bram Stoker, she was a member of the Ghost Club, a paranormal investigation and research organization, founded in London in 1862, whose membership overlapped with that of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), founded in 1882, and which included Lord Balfour. Burdett-Coutts is hinted at in Stoker’s Dracula.[28] Bram’s older brother Thornley, who read on commented on drafts of Dracula, visited Naples to meet with Burdett-Coutt’s private physician, and accompanied her on at least one cruise on the Mediterranean.[29]

The PEF was linked to Quatuor Coronati (QC) Lodge, a Masonic Lodge in London dedicated to Masonic research, to the Golden Dawn and the murders of Jack the Ripper. The PEF was founded in 1865, shortly after the completion of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem, and is the oldest known organization in the world created specifically for the study of the region of Ottoman Palestine, producing the PEF Survey of Palestine between 1872 and 1877. An ulterior motive of the PEF was intelligence gathering.[30] According to Nur Masalha the popularity of the Survey led to a growth in Zionism amongst Jews.[31]

Annie Besant’s brother-in-law, Sir Walter Besant (1836 – 1901), was an enthusiastic Freemason, becoming the third District Grand Master of the Eastern Archipelago in Singapore, one of the founding members of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge and was acting secretary of the PEF, between 1868 and 1887. Walter Besant’s main novels included All in a Garden Fair, which Rudyard Kipling credited in Something of Myself with inspiring him to leave India and make a career as a writer.[32] In 1883, he was also made a Knight of Justice of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, and in 1884 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Walter Besant also co-authored the novel The Monks of Thelema (1878) with James Rice. François Rabelais wrote of the Abbey of Thélème, built by the giant Gargantua, where the only rule is fay çe que vouldras (“Fais ce que tu veux,” or “Do what thou wilt”). Sir Francis Dashwood also employed Rabelais’s “Do what thou wilt” as the motto his Hellfire Club, as did Aleister Crowley, in his philosophy of Thelema, as set forth in his Book of the Law.

In 1867, PEF’s biggest expedition was headed by General Sir Charles Warren (1840 – 1927)—the founding Master of the Quatuor Coronati—along with Captain Charles Wilson and a team of Royal Engineers, who discovered Templar tunnels beneath the ancient Temple of Jerusalem in 1867.[33] Warren named his find the “Masonic Hall.”[34] Warren was also supportive of bringing Freemasonry to the Holy Land and PEF members were involved in the first Masonic ceremony in Palestine was held on May 7, 1873, within the cave known as Solomon’s Quarries.[35] The event was organized by Robert Morris, an American Mason, Past Grand Master of Kentucky, along with a few Masons then living in Jaffa and Jerusalem, reinforced with the presence of some visiting British naval officers with Masonic credentials. The list of those taking part included Americans, Britons, the Prussian consul, and the Ottoman Governor of Jaffa. Morris called the group the “Reclamation Lodge of Jerusalem.” Referring to the Templars, Morris. Noted that the ceremony was being held in Jerusalem for the first time “since the departure of the Crusading hosts more than seven hundred years ago.”[36]

Royal Solomon Mother Lodge

Morris was also involved in the establishment of the first real Masonic lodge in the Holy Land, after he convinced his friend William Mercer, the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Canada in the Province of Ontario, to grant a charter. The charter was issued on February 17, 1873 and Royal Solomon Mother Lodge N° 293 was formally consecrated on May 7. Signers of the petition included Charles Netter, a founding member of the Alliance Israelite Universelle, who played an instrumental role at the Congress of Berlin, and founder of Mikveh Israel. A letter to Netter from Chaim Tzvi Schneerson’s younger brother Pinchas Eliyahu, is located in the Mikveh Israel archive.[37] The first candidate to petition the lodge was Moses Hornstein, a Jew from Odessa, who had close business links with the Thomas Cook and Son travel company provided him a close a connection with the British Consulate.[38] Hornstein converted to Christianity through American missionary James Turner Barclay (1807 – 1874), known as an explorer of the Barclay Gate, an ancient gateway to the Jerusalem Temple which was sealed-off in his day, and which has since been named after him.[39] A complete description of Barclay’s Gate is found in Charles Warren’s and Claude R. Conder’s book Jerusalem, published by the PEF. Conder carried out survey work for the PEF with his old schoolmate of Lord Kitchener.[40]

Another member of the lodge was William Habib Hayat, son of the British Consul in Jaffa, Jacob Assad Hayat, who would become Master of the Jerusalem lodge in 1889. Also a member of the lodge was Christian Arab of Lebanese origin, Alexander Howard, whose real name was Iskander Awad, was also an agent for Thomas Cook. Howard’s home in Jaffa served as a Masonic Temple, where the motto in Hebrew, Shalom Al Israel is engraved over the ornate marble entrance. The legend is derived from the 18º of the Scottish Rite, Chevalier Rose-Croix. In fact, Howard called himself Le Chevalier Howard.[41]

Around 1890, his home became the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Hovevei Zion. Howard took as his assistant another founder of the lodge, Rolla Floyd, a Mormon, who succeeded him as the local agent for Thomas Cook.[42] Two further Jewish brothers of the lodge were Jacob Litwinsky and Joseph Amzalak, reportedly the wealthiest Jew in Jerusalem. Amzalak, based in Gibraltar, traded slaves to the Caribbean, but ceased this business when asked by a rabbi in Malta. Amzalak then went to live in the Holy Land, where Moses, his wealthy brother from Portugal, joined him around 1841. Haim Nissim Amzalak, Joseph’s son, acted as honorary Portuguese consul in Jerusalem from 1871, and then in Jaffa from 1886 to 1892.[43]

During the 1860’s, Hornstein rented out the upper floors of the Amzalak family home in Jerusalem to establish the Mediterranean Hotel. This was the hotel where Robert Morris organized the meetings to prepare the ceremony in King Solomon’s Quarries.[44] The hotel was of particular importance to the PEF because several of its explorers stayed there on various occasions, including Warren Conder, as well as Charles Frederick Tyrwhitt-Drake (1846 – 1874).[45] Sir Richard Burton wrote after his death that he “was my inseparable companion during the rest of our stay in Palestine, and never did I travel with any man whose disposition was so well adapted to make a first-rate explorer.”[46] The hotel was also the lodging of Mark Twain and his group when they visited Jerusalem in 1867.[47] The chronicle of Twain’s travels, which he published as The Innocents Abroad (1869), became one of the best-selling travel books of all time.

Haim Amzalak was one of the financial backers and promoters of the next Masonic lodge to be formed in Israel, the Royal Solomon Mother Lodge, officially established in Jaffa. Around 1890, a group of Arab and Jewish Masons petitioned the Misraïm Rite, based in Paris, and founded the Lodge Le Port du Temple de Salomon (“The Port of Solomon’s Temple”). The Lodge received a large number of affiliate members, French engineers who came to build the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway, the first in Palestine. In 1906, realizing that the Misraïm Rite was irregular and unrecognized by most Grand Lodges of the world, the Masons the Jaffa Lodge decided to change their affiliation to the Grand Orient of France. They adopted a new name, Barkai (“Dawn”), and eventually became integrated into the Grand Lodge of the State of Israel, and is the oldest Masonic lodge in the country still in existence.[48]

Jerusalem Lodge

From 1886 to 1888, Warren became the chief of the London Metropolitan Police during the Jack the Ripper murders. In a preface to Dracula, Stoker confessed that, “The strange and eerie tragedy which is portrayed here is completely true, as far as all external circumstances are concerned…”[49] The Jack the Ripper murders implicated the famous actor Henry Irving, who served as Stoker’s inspiration for the character Count Dracula.[50] Irving, the first actor to be knighted, ran the Lyceum Theatre where Stoker served as his business manager from 1878 to 1898. Irving had also been initiated into the Jerusalem Lodge of Freemasonry, which included the Prince of Wales (1841 – 1910), the son of Queen Victoria, later Edward VII King of England, and a close friend of Baron Nathan Rothschild, who had been installed as Most Worshipful Grand Master of the Masonic Order in England in 1875.[51] Edward’s finances had been ably managed by Sir Dighton Probyn (1833 – 1924), Comptroller of the Household, and had benefited from advice from Edward’s financier friends, some of whom were Jewish, including Ernest Cassel (1852 – 1921), Maurice de Hirsch and the Rothschild family.[52]

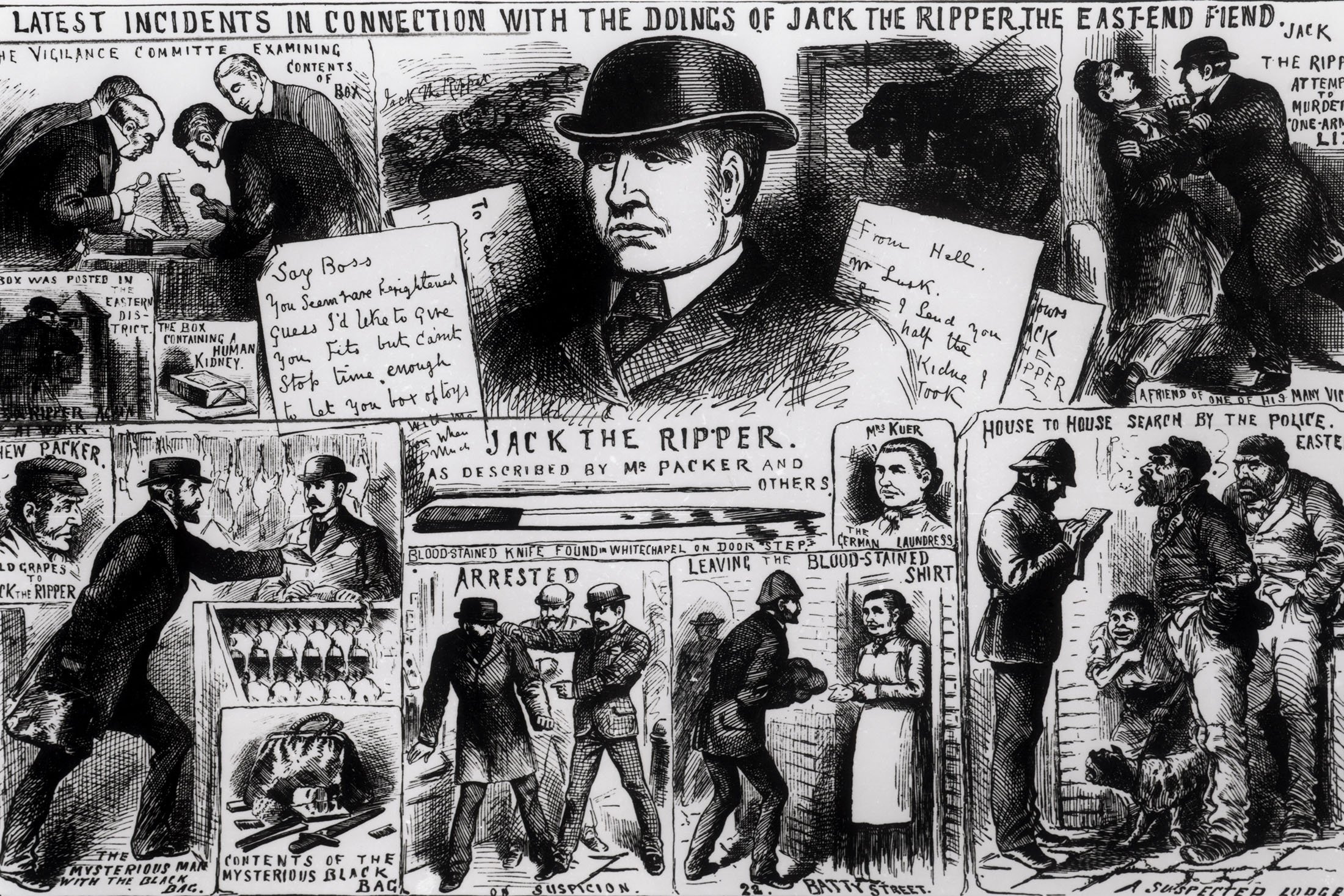

In Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, Stephen Knight proposed that the murders were part of a Masonic coverup. When it was discovered that the Prince of Wales’ son, Prince Albert Victor (1864 – 1892), had an illegitimate child with Mary Jean Kelly, whose friends numbered among Jack the Ripper’s victims, they attempted to blackmail the government. Sir William Gull, Physicians-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria and a Freemason, was called in to rectify the potential scandal. Their executions were carried out in what appeared to be ritual Masonic fashion by a group drawn from Irving’s Masonic network, Lord Salisbury who was Prime Minister at the time of the murders, and included Sir William Gull, and Lord Randolph Churchill (1849 –1895), father of future Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill.[53]

Randolph Churchill was a close friend of fellow Mason, Baron Nathan Rothschild. Churchill was a descendant of the first famous member of the Churchill family, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. Churchill’s legal surname was Spencer-Churchill, as he was related to the Spencer family, though, starting with his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, his branch of the family used the name Churchill in his public life. Winston Churchill’s mother was Jennie Jerome, daughter of American Jewish millionaire Leonard Jerome.[54] Known as the “King of Wall Street,” Jerome controlled the New York Times and had an interest in a number of railway companies and was a friend of William K. Vanderbilt.[55] Through his mother’s family, several of Churchill’s ancestors had fought in the American Revolution on behalf of the American cause. As a result, in 1947, Churchill’s was admitted as a member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut. Churchill, a Scottish Rite Freemason, was eventually invested as Knight of the Order of the Garter. He was also a member of the Ancient Order of Druids, created by Wentworth Little, founder of the SRIA.[56]

Whitechapel

According to author Stephen Senise, in Jewbaiter Jack The Ripper: New Evidence & Theory, it is not a coincidence that Britain’s most infamous unsolved crime is alleged to have been committed by a Jew, but were designed to tap that most ancient of anti-Semitic slanders, the “blood libel.” The murders took place in Whitechapel, a poverty-stricken slum in London’s East End and its surrounding neighborhoods almost exclusively Jewish, famously portrayed in Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto. In Dickens’ Oliver Twist, the den operated by Fagin, “the Jew” and ringleader of the boy thieves, was located in Whitechapel. Whitechapel was at the center of the huge late nineteenth century influx of Jewish immigration into Britain. In many parts of the East End, Jews constituted a majority of the local population. Sunday Magazine labeled the area “the Jewish colony in London.”[57]

Baron Nathan Rothschild remarked, “…We have now a new Poland on our hands in East London. Our first business is to humanise our Jewish immigrants and then to Anglicise them”[58] In 1885, Nathan Rothschild founded the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company, with of other prominent, Jewish philanthropists including Frederick Mocatta and Samuel Montagu, the MP of Whitechapel, to provide “the industrial classes with commodious and healthy Dwellings at a minimum rent.”[59] The company set out to replace the lodging houses of Whitechapel with tenements, known as “Rothschild Buildings,” designed to house mostly Jewish tenants on Thrawl Street, Flower and Dean Street, and George Street in Spitalfields, just outside the City of London.[60] Flower and Dean Street was one of the most notorious slums of the Victorian era, being described in 1883 as “perhaps the foulest and most dangerous street in the whole metropolis.”[61]

Five victims—Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly—whose murders took place between August 31 and November 9, 1888, are known as the “canonical five.” Since the murder of Mary Ann Nichols, rumors had been circulating that the killings were the work of a Jew dubbed “Leather Apron,” which had resulted in antisemitic demonstrations. In both the criminal case files and contemporary journalistic accounts, the killer was called the Whitechapel Murderer and Leather Apron. The name may be an allusion to the ceremonial aprons of Freemasonry, which were originally made of leather.[62] One Jew, John Pizer, who had a reputation for violence against prostitutes and was nicknamed “Leather Apron” from his trade as a bootmaker, was arrested but released after his alibis for the murders were corroborated.[63] Pizer had a prior conviction for a stabbing offence, and Police Sergeant William Thicke apparently believed that he had committed a string of minor assaults on prostitutes.[64]

The murder scenes were all in close proximity to Jewish establishments. Buck’s Row was opposite Brady Street Ashkenazi Cemetery; on Hanbury Street was Glory of Israel and Sons of Klatsk Synagogue; on Berner Street was St. George’s Settlement Synagogue; and Mitre Square, where Catherine Eddowes was murdered, was beside the Great Synagogue; and Miller’s Court was beside Spitalfields Great Synagogue.[65] After the murders of Stride and Eddowes in the early morning hours of September 30, Constable Alfred Long of the Metropolitan Police Force discovered a dirty, bloodstained piece of an apron in the stairwell of a tenement on Goulston Street in Whitechapel, most of whose residents were Jews.[66] Goulston Street was within a quarter of an hour’s walk from Mitre Square, on a direct route to Flower and Dean Street where Eddowes lived. The cloth was later confirmed as being a part of the apron worn by Eddowes. Above it, there was writing in white chalk on either the wall or the black brick jamb of the entranceway, with the words, “the Juwes are the men that Will not be Blamed for nothing.” This graffito became known as the Goulston Street graffito.

The Juwes

In their book The Ripper File, Elyn Jones and John Lloyd noted that the word “Juwes” was actually a Masonic reference. In the ritual of Master Mason, Hiram Abif was slain by three ruffians collectively termed The Juwes. The three “Juwes” are named as Jubela, Jubelo and Jubelum and obviously have a common root in Jubel. The ordeals attributed to the three ruffians mirror the mutilations of the victims. The throats of all the Ripper victims were cut. Chapman and Eddowes had their intestines thrown over their shoulders. In testimony, when Dr. Brown, the City Police surgeon was asked to comment on his statement that the intestines were “placed,” the coroner asked, “do you mean put there by design,” Brown answered in the affirmative.[67] Likewise, as Jones and Lloyd shown, the crimes are similar to the account of the three “Juwes” who lamented their fate:

Jubela: that my throat had been cut across, my tongue torn out…

Jubelo: that my left breast had been torn open and my heart and vitals taken from thence and thrown over the left shoulder….

Jubelum that my body had been severed in two in the midst, and divided to the north and south…[68]

However, acting as Police Commissioner, Warren feared that the Goulston Street graffito might spark anti-Semitic riots and ordered the writing washed away before dawn.[69] While most historians put the police’s failure to catch the Ripper down to incompetence, as recently as 2015, a book about the case by Bruce Robinson, titled They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper, criticized Warren as a “lousy cop” and suggested that a “huge establishment cover-up” and a Masonic conspiracy had been involved.

On October 17, after noticing that Warren had been claiming that “no language or dialogue is known in which the word Jews is spelled JUWES,” Robert Donston Stephenson (1841 – 1916), a journalist and military surgeon obsessed with the occult, wrote a letter to the City Police, claiming that a similar word did indeed exist.[70] Stephenson, however, seemed to be toying with the police as he suggested the word was a misspelling of the French Juives, for “Jews.” Stephenson, who lived near the site of the murders at the time they were committed, wrote articles claiming to know the true identity of Jack the Ripper, and that the murderer would have to be a practician of “black magic,”, derived from Éliphas Lévi’s work Le Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie.[71] Stephenson himself came under suspicion by the police and was arrested twice for the crimes but was released each time.

Tau Tria Delta

Stephenson also later fell under the suspicion of W.T. Stead. In a foreword to an article written by Stephenson in the April 1896 issue of Stead’s spiritualist journal Borderland, Stead writes that the author “prefers to be known by his Hermetic name of Tautriadelta,” and that he believed him to be Jack the Ripper. In the article itself, Tautriadelta claims to have been a student occultism under Edward Bulwer-Lytton.[72] Stephenson lived in Whitechapel, in the same lodging house where Theosophist Mabel Collins and her occultist friend Vittoria Cremers lived. After having read the book Light on the Path by Collins, Cremers felt inspired to immediately join the Theosophical Society. In 1888, she travelled to Britain to meet Blavatsky, who asked her to take over the management of the Theosophical journal Lucifer. Cremers was soon introduced to the bisexual Mabel Collins, with whom she competed for attention with Stephenson. Cremers was also a disciple of Aleister Crowley and came to believe that Stephenson was Jack the Ripper, and that in a trunk under his bed she had found five blood-soaked ties, which had supposedly become stained as a result of his cannibalism. Accepting the story as true, Crowley came to regard Stephenson as a talented black magician, and later claimed to a member of the press that he met Stephenson who had given him the five ties.[73]

Crowley reports that during his trip to America he met a man named Henry Hall who had interviewed Stead and confirmed his own diagnosis of him: “In walking down the street, Stead broke off every minute or two to indulge in a lustful description of some passing flapper and slobber how he would like to flagellate her.”[74] Stead is mentioned in an unpublished article by Crowley, titled “Jack the Ripper,” where he recounts the story between Collins, Cremers and Stephenson. However, in his characteristically enigmatic style, Crowley began the article by stating that, “It is hardly one’s first, or even one's hundredth guess, that the Victorian worthy in the case of Jack the Ripper was no less a person than Helena Petrovna Blavatsky.” Then, he notes that “persons sufficiently eminent” in matters of occult knowledge possess an “overflowing measure the sense of irony and bitter humour” and “exercise it is notably by writing with their tongues in their cheeks or making fools of their followers.” Crowley goes on to explain that reports of fraud attached to Blavatsky only served to get rid of doubters among her followers that she had no need of. Crowley then goes on to recount a story that Cremers turned Collins against Stephenson, which is why the searched through his things.

Crowley also mentions an article that appeared in Stead’s Pall Mall Gazette by Tau Tria Delta, which proposed that the murders followed prescriptions found in the grimoires of the Middle Ages, whereby a sorcerer could attain “the supreme black magical power,” including the power of invisibility. Additionally, the location of each murder formed the shape of an upside-down pentagram pointing South. Finally, after a discussion with a crime expert of the Empire News, Crowley decided to explore the possible astrological significance of the murders, and wrote he discovered that, in every case, either Saturn or Mercury were precisely on the Eastern horizon. As Crowley explained, “Mercury is, of course, the God of Magic, and his averse distorted image the Ape of Thoth, responsible for such evil trickery as is the heart of black magic, while Saturn is not only the cold heartlessness of age, but the magical equivalent of Saturn. He is the old god who was worshiped in the Witches’ Sabbath.”[75]

Kaiser Wilhelm II

In 1901, on instructions from Herzl, Joseph Cowen asked William T. Stead to arrange a meeting with Cecil Rhodes, highlighting his excellent relationship with Kaiser Wilhelm II.[76] The leaders of Zionism realized the pragmatism of securing the support of one of the European Great Powers for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Throughout the nineteenth century, not only had Germany had served as a haven, but also as a cultural and spiritual beacon for persecuted Jews from the ghettos of eastern Europe. And while largely east European in origin, the Zionist leadership was almost entirely German or German-educated Jews from eastern Europe, despite the overwhelmingly liberal, assimilationist, and anti-Zionist inclinations of German Jews. Berlin, in effect, emerged as an important center of the fledgling international Zionist movement. As explained by Francis R. Nicosia, in The Third Reich and the Palestine Question, it was in recognition of Germany’s growing political and economic ties to the Ottoman Empire and its strategic aims in the Middle East that “the Zionist movement sought to become a willing instrument in the formulation and pursuit of German foreign policy.”[77]

Herzl’s friend Arminius Vambery was a strong supporter of British expansionism and also served as foreign consultant to Abdul Hamid II. In that position, he introduced Herzl to the Sultan in 1901. In his diaries, Herzl devotes many pages to describing his encounters with Vambery and repeatedly acknowledges his contributions to the Zionist cause. While Max Nordau claims that it was he who first introduced Herzl to Vambery in 1898, Herzl identified William Hechler (1845 – 1931), an English clergyman of German descent who became a close friend of Herzl, as the one who introduced him to Vambery in 1900 in his efforts to meet with the Sultan.[78] It was also Hechler who assisted Herzl in his attempts to recruit Kaiser Wilhelm II to the Zionist cause. Hechler’s interest in Jewish studies and Palestine evolved under the influence of Restorationism, a term that was eventually replaced by Christian Zionism. He began developing his own eschatological theories and timelines for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. In 1854, Hechler returned to London and took a position with the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews.

By 1873, Hechler became the household tutor to the children of Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden (1826 – 1907). Through Frederick’s son Ludwig, Hechler developed a relationship with the young Kaiser Wilhelm II. Hechler’s wife had been a student of one of the Kaiser’s closest friends and suspected homosexual lover Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg (1847 – 1921). Philipp was a diplomat and composer of Imperial Germany who achieved considerable influence through his friendship with the Kaiser, who shared his interest in the occult.[79] Eulenburg became very close to the French diplomat, writer and racist Count Arthur de Gobineau, whom Eulenburg was later to call his “unforgettable friend.”[80] Eulenburg was deeply impressed by Gobineau’s An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races.[81] Gobineau would later to write that only two people in the world who properly understood his racist philosophy were Richard Wagner and Eulenburg.[82]

In 1876, Gobineau accompanied his close friend Pedro II on his trip to Russia, Greece and the Ottoman Empire. Gobineau introduced him to both Emperor Alexander II of Russia and Sultan Abdul Hamid II. After leaving Pedro II in Constantinople, Gobineau traveled to Rome, Italy, for a private audience with Pope Pius IX.[83] During his visit to Rome, Gobineau met and befriended the Richard Wagner and his wife Cosima.[84] Wagner helped popularize Gobineau’s racial theories his newspaper Bayreuther Blätter. Gobineau in turn became a member of the Bayreuther Kreis (“Bayreuth Circle”), which included Wagner’s son-in-law, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who became a close friend of Eulenburg, who shared Chamberlain’s love of Wagner’s music. Besides being a passionate Wagnerite, Eulenburg also found much to admire in Chamberlain’s anti-Semitic, anti-British and anti-democratic writings.[85]

Eulenburg played an important role in the rise of Bernhard von Bülow (1849 – 1929), a German statesman who fell from power in 1907 due to the Harden–Eulenburg affair when he was accused of homosexuality. The Harden–Eulenburg affair was a scandal involving accusations of homosexual conduct among prominent members of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s cabinet and entourage during 1907–1909. The affair centered on journalist Maximilian Harden’s accusations of homosexual conduct between the Eulenburg and General Kuno, Graf von Moltke.[86] Moltke was forced to leave the military service. Despite his anti-Semitism, during his time as Ambassador to Austria, Eulenburg engaged in a homosexual relationship with the Austrian Jewish banker Nathaniel Meyer von Rothschild (1836 – 1905), grandson of Salomon Mayer von Rothschild, founder of the Austrian branch of the family.[87] Salomon retained ties with Prince Metternich. Salomon was also a member of the Frankfurt Judenloge.[88]

Kaiser Wilhelm II as well was a known anti-Semite. Lamar Cecil, Wilhelm II’s biographer noted that in 1888 a friend of his “declared that the young Kaiser’s dislike of his Hebrew subjects, one rooted in a perception that they possessed an overweening influence in Germany, was so strong that it could not be overcome.” Cecil concludes:

Wilhelm never changed, and throughout his life he believed that Jews were perversely responsible, largely through their prominence in the Berlin press and in leftist political movements, for encouraging opposition to his rule. For individual Jews, ranging from rich businessmen and major art collectors to purveyors of elegant goods in Berlin stores, he had considerable esteem, but he prevented Jewish citizens from having careers in the army and the diplomatic corps and frequently used abusive language against them.[89]

Hechler’s Restorationist theology resonated with the Grand Duke of Baden, who would play a pivotal role in the history of the Zionist movement.[90] While serving as Chaplain of the British Embassy in Vienna, Hechler, who had read Herzl’s Der Judenstaat, visited Herzl in 1896. Hechler arranged an extended audience with the Grand Duke in 1896. The Grand Duke in turn spoke with Kaiser Wilhelm II in October 1898 about the Zionists’ ideas. Hechler arranged an introduction for Herzl to Eulenburg. On October 7, 1898, Eulenburg summoned Herzl to Liebenberg to announce that Wilhelm II wanted to see a Jewish state established in Palestine (which would be a German protectorate) in order to “drain” the Jews away from Europe, and thus “purify the German race.”[91] In Berlin, Herzl had already negotiated with the German Chancellor Prince Hohenlohe, and with Eulenburg’s friend Bernard von Billow, the Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, and he believed that a Jewish state in Palestine was close at hand. Through the efforts of Hechler and the Grand Duke, Herzl publicly met Wilhelm II in 1898. The Kaiser assured Herzl of his support for the Jewish protectorate under Germany. They decided that Herzl, and his associate Max Bodenheimer (1865 – 1940, the first president of the Zionist Federation of Germany (ZVfD) and one of the founders of the Jewish National Fund, and David Wolffsohn (1855 – 1914), the Cologne banker who was later elected to succeed Herzl as head of the WZO after his death in 1904, should head for the Near East.[92] A week later, Herzl and the Kaiser met again in Jerusalem, at the village of Mikveh Israel, founded in 1870 by Charles Netter. The meeting significantly advanced Herzl’s and Zionism’s legitimacy in Jewish and world opinion. [93]

[1] Nicholas de Vere. The Dragon Legacy: The Secret History of an Ancient Bloodline (Book Tree, 2004) p. 22.

[2] Israel Cohen. Thedor Herz: Founder of Political Zionism (New York: Thomas Yoseloff), p. 251.

[3] Fritz Stern. Gold and Iron: Bismarck, Bleichröder and the Building of the German Empire, p. 17.

[4] “The Knight of Noble Consciousness.” Volume 12 (New York, 1854), p. 479

[5] Harry W. Rudman. Italian Nationalism and English Letters (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1940), p. 61; Joseph Michael Kelly. “The Parliamentary Career of Joseph Cowen.” (Loyola University Chicago, 1970). Dissertations. 1031.

[6] Leonard Stein. The Balfour Declaration (Simon & Schuster, 1961).

[7] Petra Wilhelmy-Dollinger, in “Berlin Salons: Late Eighteenth to Early Twentieth Century.” Jewish Women’s Archive. Retrieved from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/berlin-salons-late-eighteenth-to-early-twentieth-century

[8] Thomas Fowler & John Malcolm Mitchell. “Shaftesbury, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of.” In Hugh Chisholm (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica, Vol. 24, 11th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1911), pp. 763–765.

[9] Donald Lewis. The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftesbury And Evangelical Support For A Jewish Homeland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 380.

[10] “CMJ UK - The Church’s Ministry among Jewish People.” www.cmj.org.uk.

[11] Kelvin Crombie. A Jewish Bishop in Jerusalem: the life story of Michael Solomon Alexander (Jerusalem: Nicholayson’s, 2006).

[12] Joseph Cotton Wigram. Report of the Conference upon the Rosenthal case, held with the representatives of the Committee of the London Society for promoting Christianity amongst the Jews (London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer (1866), p. 2. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=zzUYUmy91t0C&pg=PA2

[13] Nicolaevsky & Maenchen-Helfen. Karl Marx, pp. 4–6.

[14] R. Larry Todd. Mendelssohn – A Life in Music (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. 2003), p. 33.

[15] Clive Brown. A Portrait of Mendelssohn (New Haven and London: Yale University Press. 2003), p. 84.

[16] Laura K.T. Stokes. “Mendelssohn’s Deutsche Liturgie in the Context of the Prussian Agenda of 1829.” In Rethinking Mendelssohn, ed. Benedict Taylor Ph.D. (Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 347.

[17] Barbara W. Tuchman. Bible and Sword (London: PAPERMAC, 1984).

[18] Sidney Lee (ed). “M’Caul, Alexander.” Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35 (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1893).

[19] Elizabeth Anne McCaul Finn. Reminiscences of Mrs. Finn, Member of the Royal Asiatic Society (Marshall, Morgan and Scott, 1929), p. 254.

[20] “Palestine Exploration Fund.” Quarterly Statement for 1875 (London, 1875). p. 116.

[21] Markus Kirchhoff. “Surveying the Land: Western Societies for the Exploration of Palestine, 1865-1920.” Benedikt Stuchtey (ed.). Science across the European Empires, 1800-1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 156.

[22] Howard. Secret Societies; Goodrick-Clarke. The Occult Roots of Nazism, p. 113.

[23] “The Knight of Noble Consciousness.” MEWC, Volume 12 (New York, 1854), p. 479

[24] David Loades. (ed.) Reader's guide to British history (2nd ed.) (New York: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2003). pp. 1138–1139.

[25] John Isbell. “Introduction,” Germaine De Stael, Corinne, or, Italy, trans. Sylvia Raphael (Oxford: Worlds Classics, 1998), p. ix.

[26] “Baroness Burdett-Coutts.” Henry Poole & Co. Retrieved from https://henrypoole.com/individual/baroness-burdett-coutts/

[27] Sally Davis. “Work on the members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.” Roger Wright & Sally Davis. Retrived from http://www.wrightanddavis.co.uk/GD/CARDENS.htm

[28] Bernard Davies. “Inspirations, Imitations and In-Jokes in Stoker’s Dracula,” in Dracula: The Shade and the Shadow, ed. Elizabeth Miller (Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex: Desert Island Books, 1998), 131-137. Cited in Hans Corneel de Roos. “Bram Stoker’s Hidden World: A Sociogram of London’s Esoteric Circles.” www.vampvault.jimdofree.com

[29] Rickard Berghorn. “Dracula’s Swedish Cousin: A Great Literary Mystery,” in Bram Stoker & A-e. Owners of Darkness: The Unique Version of Dracula (Centipede Press 2022), p. 21.

[30] Kathleen Stewart Howe. Revealing the Holy Land: the photographic exploration of Palestine (University of California Press, 1997). p 37

[31] Nur Masalha. Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History (Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), p. 256b.

[32] Letters of George Gissing to members of his family, collected and arranged by Algernon and Ellen Gissing (London: Constable, 1927), letter dated 6/3/1884.

[33] Ben-Dov. In the Shadow of the Temple, p. 347

[34] Rupert L. Chapman III. Tourists, Travellers and Hotels in 19th-Century Jerusalem: On Mark Twain and Charles Warren at the Mediterranean Hotel (Routledge, 2018).

[35] Ibid.

[36] Leon Zeldis. “Jewish and Arab Masons in the Holy Land: Where Ideas can Fashion Reality.” First Regular Meeting of Quatuor Coronati Lodge 112 Regular Grand Lodge of Italy (Rome, March 20, 2004). Retrieved from http://www.freemasons-freemasonry.com/zeldis12.html

[37] Israel Klausner. רבי חיים צבי שניאורסון : ממבשרי מדינת ישראל. (Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1973).

[38] Rupert L. Chapman. “The Mediterranean Hotel in 19th Century Jerusalem.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 127 (1995), p. 100.

[39] “Moses HORNSTEIN (1826 - 1885).” Khan’s Kin Folk. Retrieved from http://www.khanskinfolk.com/HTMLFiles/HTMLFiles_02/P554.html

[40] John Charles Pollock. Kitchener: the road to Omdurman (Constable, 1998), p. 23.

[41] Leon Zeldis. “Freemasonry In Israel.” Retrived from http://www.skirret.com/papers/freemasonry_in_israel.html

[42] “Moses HORNSTEIN (1826 - 1885).”

[43] Joseph B. Glass & Ruth Kark. Sephardi Entrepreneurs in Eretz Israel: The Amzalak Family 1816-1918 (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1991), pp. 50-53, 56-61, 84, 123-126.

[44] “Moses HORNSTEIN (1826 - 1885).”

[45] Chapman. “The Mediterranean Hotel in 19th Century Jerusalem,” p. 100.

[46] Charles Frederick Tyrwhitt-Drake. The Literary Remains of the Late Charles F. Tyrwhitt Drake (R. Bentley, 1877), p. 16.

[47] “Moses HORNSTEIN (1826 - 1885).”

[48] Zeldis. “Freemasonry In Israel.”

[49] Formáli höfundarins in Makt Mykranna. (Reykjavik, Iceland: Nokkrir Prentarar, 1901). p. 3-4. Translated from the Icelandic by Silvia Sigurdson, (Transylvania Press, Inc. 2004).

[50] John Pick & Robert Protherough. “The Ripper and the Lyceum: The Significance of Irving’s Freemasonry.” The Irving Society. Retrieved from http://www.theirvingsociety.org.uk/ripper_and_the_lyceum.htm; Lewis S. Warren, “Buffalo Bill Meets Dracula: William F. Cody, Bram Stoker, and the Frontiers of Racial Decay,” American Historical Review, Vol. 107, No. 4, (October 2002).

[51] Austin Brereton. The Life of Henry Irving, (Longmans Green & Co., 1908). Vol 1 p. 234.

[52] Keith Middlemas. Antonia Fraser (ed.). The Life and Times of Edward VII (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972), pp. 38, 84, 96; J. B. Priestley. The Edwardians (London: Heinemann, 1970), p. 32.

[53] Stephen Knight. Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, (Harrap, 1976); Melvyn Fairclough. The Ripper and the Royals, (Duckworth, 1992).

[54] Moshe Kohn. The Jerusalem Post (January 18, 1993).

[55] Edwin G. Burrows & Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

[56] Clifford Shack. The Rothschilds, Winston Churchill and the "Final Solution. http://www.hiddenmysteries.org/conspiracy/history/hitlerchurchhill.html

[57] Robert Philpot. “Were the Jack the Ripper murders an elaborate anti-Semitic frameup?” Times of Israel (July 13, 2017).

[58] Jim Leen. “Jacob the Ripper?” Casebook: Jack the Ripper. Retrieved from https://www.casebook.org/dissertations/jacob-the-ripper.html

[59] Jerry White. Rothschild Buildings: Life in an East-End Tenement Block 1887 - 1920 (Random House, 2011).

[60] Jewish Chronicle (December 10, 1886).

[61] James Greenwood. In Strange Company (1883), pp. 158-60, cited in Jerry White. London in the Nineteenth Century (2007), p. 323.

[62] F.R. Worts. “The apron and its symbolism.” Transations of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge, No. 2076, London.

[63] Donald Rumbelow. The Complete Jack the Ripper (Penguin Books, 2004), pp.49–50.

[64] Trevor Marriott. Jack the Ripper: The 21st Century Investigation (London: John Blake, 2005), p. 251.

[65] Jim Leen. “Jacob the Ripper?” Casebook: Jack the Ripper. Retrieved from https://www.casebook.org/dissertations/jacob-the-ripper.html

[66] Robert Philpot. “Were the Jack the Ripper murders an elaborate anti-Semitic frameup?” Times of Israel (July 13, 2017).

[67] Thomas Toughill. Ripper Code (The History Press, May 30, 2012).

[68] A Ritual, and Illustrations of Free-Masonry, and the Orange and Odd Fellows’ Societies, accompanied by ... engravings, and a key to the Phi Beta Kappa by Avery Allyn, also an Account of the Kidnapping and Murder of William Morgan ... Abridged from American authors. By a Traveller in the United States (S. Thome, 1848), p. 89.

[69] Letter from Charles Warren to Godfrey Lushington, Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Home Department, 6 November 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, cited in Evans and Skinner. The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, pp. 183–184.

[70] Stewart P. Evans & Keith Skinner. The Ultimate Jack The Ripper Sourcebook (London: Robinson, 2000), p. 668.

[71] Melvin Harris. Jack the Ripper: The Bloody Truth (1987).

[72] Tautriadelta. “A Modern Magician: An Autobiography. By a Pupil of Lord Lytton.” Borderland 3, no. 2 (April 1896).

[73] Lawrence Sutin. Do What Thou Wilt: A life of Aleister Crowley (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), p. 228

[74] Aleister Crowley. The Confessions of Aleister Crowley (New York: Hill & Wang, 1969).

[75] Aleister Crowley. “Jack the Ripper.” Retrieved from https://www.casebook.org/dissertations/collected-donston.8.html

[76] Israel Cohen. Thedor Herz: Founder of Political Zionism (New York: Thomas Yoseloff), p. 251.

[77] Nicosia. The Third Reich and the Palestine Question, p. 1.

[78] David Mandler. Arminius Vambéry and the British Empire: Between East and West (Lexington Books, 2016), p. 146.

[79] John Röhl. The Kaiser and His Court (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 61-62, 66.

[80] Ibid., pp. 33 & 54.

[81] Ibid., p. 171.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Gregory Blue. “Gobineau on China: Race Theory, the ‘Yellow Peril’ and the Critique of Modernity.” Journal of World History, 10: 1 (1999), pp. 96–7.

[84] Ibid., p. 115.

[85] Ian Buruma. Anglomania: A European Love Affair (New York: Vintage Books, 2000), p. 218.

[86] Röhl. The Kaiser and His Court, p. 57.

[87] Norman Domeier. The Eulenburg Affair: A Cultural History of Politics in the German Empire (Rochester: Boydell & Brewer, 2015), p. 176.

[88] Katz. Jews and Freemasonry.

[89] Lamar Cecil. Wilhelm II: Prince and Emperor, 1859–1900 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989).

[90] Polkehn. “Zionism and Kaiser Wilhelm,” pp. 78.

[91] Domeier. The Eulenburg Affair, p. 177.

[92] Bodenheimer. So Wurde Israel, p. 95.

[93] London Daily Mail (November 18, 1898).

Zionism

Introduction

Kings of Jerusalem

The Knight Swan

The Rose of Sharon

The Renaissance & Reformation

The Mason Word

Alchemical Wedding

The Invisible College

The New Atlantis

The Zoharists

The Illuminati

The American Revolution

The Asiatic Brethren

Neoclassicism

Weimar Classicism

The Aryan Myth

Dark Romanticism

The Salonnières

Haskalah

The Carbonari

The Vormärz

Young America

Reform Judaism

Grand Opera

Gesamtkunstwerk

The Bayreuther Kreis

Anti-Semitism

Theosophy

Secret Germany

The Society of Zion

Self-Hatred

Zionism

Jack the Ripper

The Protocols of Zion

The Promised Land

The League of Nations

Weimar Republic

Aryan Christ

The Führer

Kulturstaat

Modernism

The Conservative Revolution

The Forte Kreis

The Frankfurt School

The Brotherhood of Death

Degenerate Art

The Final Solution

Vichy France

European Union

Eretz Israel