19. The Carbonari

Palladian Rite

The two authors at the time shared a conclusion that the Illuminati, founded in 1776 by Adam Weishaupt (1717 – 1753), were the source of the French Revolution. In 1797, the Abbé Augustin de Barruel (1741 – 1820), an ex-Jesuit who came to Britain following the September Massacre, published the first volumes of his four-volume account of the French Revolution, Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism. That same year, John Robison (1739 – 1805), professor of natural philosophy at Edinburgh, published his own history of the Revolution, Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the religions and governments of Europe. Like Robison, Barruel claimed that the French Revolution was the result of a deliberate conspiracy subvert the power of the Catholic Church and the aristocracy, hatched by a coalition of philosophes, Freemasons and the Order of the Illuminati. About the higher mysteries of the Illuminati, which were shared only by Weishaupt himself, Robison related that the publisher of the Neueste Arbeitung reported:

…that in the first degree of Maous or PHILOSOPHUS, the doctrines are the same with those of Spinoza, where all is material, God and the world are the same thing, and all religion whatever is without foundation, and the contrivance of ambitious men.[1]

Heinrich Heine (1797 – 1856), a Freemason and a close friend of Marx and the Rothschilds, and also born Jewish, pronounced the same observations usually denounced as among the worst examples of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories when he declared, “money is the God of our time and Rothschild is his prophet.”[2] Heine listed Nathan Mayer Rothschild as one of the “three terroristic names that spell the gradual annihilation of the old aristocracy,” alongside Cardinal Richelieu and Maximilien Robespierre.[3] According to Heine:

No one does more to further the revolution than the Rothschilds themselves… and, though it may sound even more strange, these Rothschilds, the bankers of kings, these princely pursestring-holders, whose existence might be placed in the gravest danger by a collapse of the European state system, nevertheless carry in their minds a consciousness of their revolutionary mission.[4]

In 1806, Barruel received a letter from Jean-Baptiste Simonini, captain in the Piedmontese, which first congratulated him for having “unmasked the hellish sects which are preparing the way for Antichrist,” but then criticized him for sparing the “Judaic sect” from his study, who he claimed were the real “Unknow Superiors,” behind the conspiracy. Realizing this must seem like an exaggeration, Simonini related a personal account, where explained that during the revolutionary years he had impersonated a Jew while living in Turin. The Jews showed him “sums of gold and silver for distribution to those who embraced their cause,” and promised to make him a general on the condition that he become a Freemason.[5]

The Simonini letter, explains Norman Cohn, “seems to be the earliest in the series of antisemitic forgeries that was to culminate in the Protocols.”[6] After presenting Simonini with three weapons bearing Masonic symbols, his Jewish confidants revealed their greatest secrets: Mani (216 – 277), the prophet of the Gnostic sect of the anaeism was Jewish, as was Hasan-i Sabbah, also known as the “Old Man of the Mountain,” cult leader of the Ismaili Assassins, who are reputed to have imparted their occult knowledge to the Templars. Some Masons believed that Falk was the “Old Man of the Mountain.”[7] The Freemasons and the Illuminati were both founded by Jews. They would use money to take over governments and usury to rob Christian populations. In less than a century, they would be masters of the world. More immediate goals were full emancipation and the annihilation of the Jews’ worst enemy, the House of Bourbon.[8]

The Jews also boasted that they had already infiltrated the Catholic clergy, up to the highest echelons, and aimed to someday succeed in having one of their own elected pope.[9] A similar plot was revealed when Pope Leo XIII (1810 – 1903) requested the publication of the Alta Vendita. It was first published by Jacques Crétineau-Joly (1803 – 1875) in The Church and the Revolution. The pamphlet was popularized in the English-speaking world by Monsignor George F. Dillon in 1885 with his book The War of Anti-Christ with the Church and Christian Civilization. Astoundingly, the document exposes the details a Masonic plot to infiltrate the Catholic Church and ultimately install a Masonic pope.[10] According to the document:

Our ultimate end is that of Voltaire and of the French Revolution—the final destruction of Catholicism, and even of the Christian idea…

The Pope, whoever he is, will never come to the secret societies; it is up to the secret societies to take the first step toward the Church, with the aim of conquering both of them.

The task that we are going to undertake is not the work of a day, or of a month, or of a year; it may last several years, perhaps a century; but in our ranks the solider dies and the struggle goes on.[11]

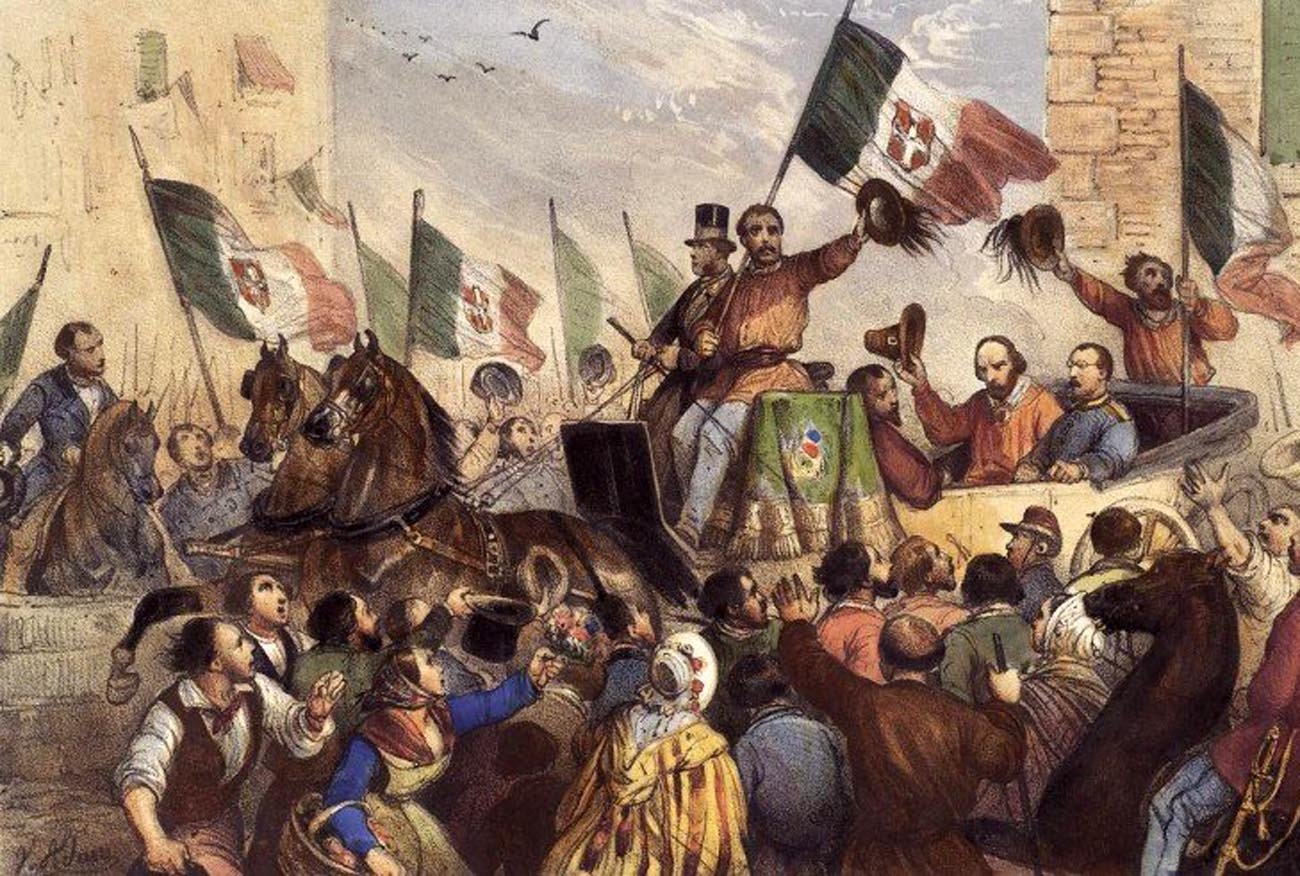

The Alta Vendita, a text purportedly produced by the highest lodge of the Italian Carbonari and written by Giuseppe Mazzini (1807 – 1872)—who was widely reputed to have succeeded to leadership of the Illuminati after Weishaupt’s death—leader of the Risorgimento, the revolutionary movement that led to the Unification of Italy and the end to more than a thousand years of the reign of the Papal States by the papacy. Mazzini held a high position among the Florentine Masons, and served as Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy, as did Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807 – 1882), who are both considered among of Italy’s “fathers of the fatherland,” along with Count of Cavour (1810 – 1861) and Victor Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy (1820 – 1878). The House of Savoy descended from Charles Emmanuel I, whose birth was prophesied by Nostradamus, and had links with the House of Habsburg and the Order of the Golden Fleece, and who claimed the hereditary title of Kings of Jerusalem. [12] Victor Immanuel II’s mother was Maria Theresa of Austria (1801 – 1855), who was the double granddaughter of Empress Maria Theresa and Francis I. Like his father, Victor Emmanuel II was a knight of the Order of the Garter as well as knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. In 1904, when Theodor Herzl, the founder of Zionism, met with of Victor Emmanuel II’ grandson, Victor Emmanuel III of Italy (1869 – 1947), he revealed that one of his ancestors had been a co-conspirator of Shabbetai Zevi.[13]

Mazzini worked closely with Lord Palmerston, who was twice Prime Minister, holding office continuously from 1807 until his death in 1865, and dominated British foreign policy during the period 1830 to 1865, when Britain was at the height of its imperial power. “In his time,” as noted by Stefano Recchia and Nadia Urbinati, Mazzini “ranked among the leading European intellectual figures, competing for public attention with Mikhail Bakunin and Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville.”[14] Mazzini argued for a reorganization of the European political order on the basis of two primary principles: democracy and national self-determination. To him, the nation was a necessary intermediary step in the progressive association of mankind, the means toward a future international “brotherhood” of humanity. Mazzini even conceived that Europe’s nations might one day be able to join together in a “united States of Europe.”[15]

In response, in 1884, Pope Leo XIII published his condemnation of Freemasonry, the encyclical Humanum genus. Leo Taxil (1854 – 1907), who published his notorious hoax, Le Diable au XIXe siècle (“The Devil in the 19th Century”) in 1892, and even succeeded in gaining the Leo XIII’s endorsement for his anti-Masonic writings. Taxil, whose real name was Gabriel Jogand-Pagés, was a swindler and the author of various screeds against the Catholic Church, but who later claimed to have repented and converted to Catholicism. In Le Diable au XIXe siècle, writing under the name of Dr. Bataille, and in collaboration with Domenico Margiotta, a former high-ranking Freemason, Taxil revealed the existence of the so-called Palladian Rite, a Luciferian rite that was the pinnacle of Masonic power. However, in 1897, Taxil finally confessed that the revelations about the Palladian Rite were a hoax, causing quite a scandal. Margiotta too confessed, declaring that he invented all such stories after he signed a “barbarous contract” with Taxil. Afterwards, Margiotta was never seen or heard from again.[16]

Curiously, however, Taxil was close to Giuseppe Garibaldi, Mazzini’s co-conspirator, who also was supposedly a founding member of the Palladian Rite that Taxil originally claimed to expose.[17] Mazzini, along with Otto von Bismarck (1815 – 1898), and Albert Pike (1809 – 1891), all thirty third degree Scottish Rite Masons, supposedly completed an agreement to create a supreme universal rite of Masonry that would arch over all the other rites. Civil War General Albert Pike was Sovereign Commander Grand Master of the Supreme Council of Scottish Rite Freemasonry in Charleston, South Carolina, and the reputed founder of the notorious Ku Klux Klan (KKK).[18] Pike, in honor of the Templar idol Baphomet, named the order the New and Reformed Palladian Rite or New and Reformed Palladium. The Palladian Rite was to have been an international alliance to bring in the Grand Lodges, the Grand Orient, the ninety-seven degrees of Memphis and Misraïm of Cagliostro, also known as the Ancient and Primitive Rite, and the Scottish Rite, or the Ancient and Accepted Rite. Also according to Margiotta, Rothschild agent Gerson von Bleichröder—a member of the Gesellschaft der Freunde, founded by leading members of the Haskalah in the circle of Moses Mendelssohn and the Hamburg Temple—also financed Otto von Bismarck’s plans for the unification of Germany.[19]

Barruel was irritated that he hadn’t discovered this connection himself. He tried to verify the authenticity of the letter by writing to various authorities, including important bishops. After being told that Simonini could be trusted, Barruel began to study the Jewish history of his conspiracy theory intensely. Barruel chose not to publicize the letter, fearing it might incite violence against the Jews, but nevertheless circulated it among influential circles in France. Barruel confessed on his deathbed that he had written a new manuscript incorporating the Jews into his Masonic conspiracy theory. Although Barruel had been more convinced that a Masonic conspiracy led the revolution, and although many Jews were Freemasons, they did not act alone. The current leadership of the conspiracy, he reported, was a council of 21, 9 of whom were Jews. However, he burned this manuscript two days before his death. He wrote that he wanted to prevent a massacre against Jews.[20]

Young Italy

Many Jews joined Giovane Italia (“Young Italy”), which was founded by Mazzini in 1831 and soon supplanted the Carbonari.[21] Sarina Nathan, or Sara Levi Nathan (1819 – 1882), was the financier and confidant of Mazzini and promulgator of his ideas and works. The secretary and faithful friend of Count Cavour was Isaac Artom (1829 – 1900), a Jewish Italian diplomat and politician, while Salomon Olper, later rabbi of Turin, was the friend and counselor of Mazzini. The patriotism of the Jews soon won them the support of the leading liberals and served to popularize among them the cause of Jewish emancipation. Later, in 1834, Count Cavour began a campaign in favor of Jewish emancipation in the newspaper II Risorgimento. A similar campaign was undertaken by Mazzini, who in Jeune Suisse of November 4, 1835, he wrote:

We claim that the best way of making good citizens of the Jews, whenever they may not meet the standard, is to make brothers of them, equal to everybody else under the law; we claim that wherever this has been done, the religious sect that has given Europe men of such intelligence as Spinoza and Mendelssohn, has rapidly improved.[22]

As pointed out by R. John Rath, because of a various similarities like their means of correspondence, some recent scholars like Carlo Francovich and Arthur Lehning have argued that the Carbonari were organized by the Illuminati.[23] The Carbonari were formed through the influence of Philippe Buonarroti (1761 – 1837), a descendant of Michelangelo’s brother, who attended the University of Pisa and studied law. Historian Carlo Francovich asserted that in 1786 Buonarroti also joined an Illuminati lodge in Florence.[24] Buonarroti became editor of the revolutionary Corsica paper, Giornale Patriottico di Corsica (1790), operated by Illuminatus Baron de Bassus, who referred to him by the Jewish alias of Abraham Levi Salomon.[25] According to historian James H. Billington, its first issues specifically identified the French Revolution with the Illuminati, and praised all the social upheavals taking place in Europe.[26] By March of 1793, Buonarroti made his way to France, where he joined meetings of the Jacobins, and befriending Robespierre, “for whom he kept a great veneration all his life.”[27]

Buonarroti was a leader of the Illuminati cover, the Philadelphes.[28] According to Wit von Dörring, a former member who became a police informer, the aims of the Carbonari were the same as the Illuminati, to “destroy every positive religion and every form of government, whether unlimited despotism or democracy,” and were revealed in the final grade.[29] It has long been assumed that members of the Philadelphes and the Adelphes of Italy, or the Sublimes Maîtres Parfaits, had founded the Carbonari.[30] Arrested on March 5, 1794, Buonarroti was sentenced to serve time at Du Plessis prison in Paris, where he had met and befriended François-Noël (Gracchus) Babeuf, a member of the revolutionary Social Circle established by Bode’s disciple, Nicholas Bonneville.[31] Buonarroti was freed after nine years, when he began to organize a multitude of revolutionary secret societies. The High Court at Vendome sentenced Buonarroti to deportation, and he sent to the Island of Re before finally being permitted by Napoleon to move to Geneva in 1806. Soon after settling in Geneva, Buonarroti was initiated into the Grand Orient Lodge Des Amis Sincères, and is recorded as being its Venerable Master in 1811, under the alias Camille.[32] As soon as Buonarroti became a member, he immediately formed an inner circle within the Lodge, a “secret group of Philadelphes,” the same name assumed by the Illuminati in Paris.[33]

Shortly after, Buonarroti founded his most important secret society: the Sublimes Maîtres Parfaits (“Sublime Perfect Masters”), which represented a merging of the Philadelphes from France and Switzerland and its Italian branch, the Adelphes, formed around 1807, headed by Buonarroti’s friend Luigi Angeloni (1758 – 1842).[34] The aim was no longer exclusively to fight Napoleon in France and Italy and the establishment of a republican regime,” explains Lehning. “It now became an international society of European revolutionaries with the purpose to republicanise Europe.”[35] According to Wit von Dörring, a former member who became a police informer, the aims of the Carbonari were the same as the Illuminati, to “destroy every positive religion and every form of government, whether unlimited despotism or democracy,” and were revealed in the final grade.[36] It has long been assumed that members of the Philadelphes and the Adelphes of Italy, or the Sublimes Maîtres Parfaits, had founded the Carbonari.[37]

In 1833–34 the first abortive Mazzinian uprisings took place in Piedmont and Genoa. The latter was organized by Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had joined Young Italy, then fled to France. After an attempt to instigate insurrection in Savoy in 1834 without the blessing of Buonarroti, Mazzini and his followers were summarily excommunicated by a circular from Buonarroti’s Charbonnerie Démocratique Universelle.[38] In 1836, Mazzini left Switzerland and settled in London. Under Lord Palmerston’s guidance, Mazzini had organized all his revolutionary sects: Young Italy, Young Poland, Young Germany which were under the aegis of Young Europe.[39] He spent most of the next two decades in exile or hiding, expanding the organization into his series of national liberation guerrilla movements. Young Europe was the culmination of these groups, which led to him being called by Metternich, “the most dangerous man in Europe.”

Communist League

The revolutionaries spoke of Buonarroti as “an occult power whose shadowy tentacles extended… over Europe.”[40] The Philadelphes were eventually affiliated with the Rite of Memphis, a brand of Egyptian Freemasonry closely associated with the Rite of Misraïm, which had its origins with Cagliostro and Jacob Falk.[41] A great number of Frankists who had joined the Rite of Memphis participated in a spree of Marxist-inspired subversive movements, known as the Year of Revolutions of 1848.[42] In discussing the fallout of 1848, Karl Marx (1818 – 1883), remarked: “[E]very tyrant is backed by a Jew, as is every Pope by a Jesuit.”[43]

Buonarroti’s work became a bible for revolutionaries, inspiring such leftists as Marx. Indeed, Marx and Friedrich Engels (1820 – 1895), a half-century later in their first joint work The Holy Family (1844), were eager to concede their debt to Bonneville’s enterprise:

The revolutionary movement which began in 1789 in the Cercle Social, which in the middle of its course had as its chief representatives Leclerc and Roux, and which finally with Babeuf’s conspiracy was temporarily defeated, gave rise to the communist idea which Babeuf’s friend Buonarroti re-introduced in France after the Revolution of 1830. This idea, consistently developed, is the idea of the new world order.[44]

Marx was tutored in communism by Moses Hess, an ardent admirer of Mazzini.[45] Moses Hess also befriended the “ingenious, prophetic Heine,” as he called him in his unpublished diary of 1836.[46] Heine, who was born in Dusseldorf was called “Harry” in childhood but became known as “Heinrich” after his conversion to Lutheranism in 1825. Heine referred to baptism as the “admission ticket” to European culture, which, as noted David Bakan, was typically associated with Sabbateanism.[47] Heine was also a relative of Isaac Bernays, the neo-Orthodox Hakham involved in the Hamburg Temple disputes, and refers to him repeatedly in his letters.[48] Together with Leopold Zunz, a preacher from the Hamburg Temple, other young men, Heine founded the Verein für Kultur und Wissenschaft der Juden (“The Society for the Culture and Science of the Jews”) in Berlin in 1819. Heine and his fellow radical exile in Paris, Ludwig Börne (1786 – 1837), a Jewish convert to Lutheranism, were leading members of Mazzini’s Young Germany. Börne was a close friend of Mark Herz, a close friend of Moses Mendelssohn and David Friedländer, and husband of the salonnière Henriette Herz, and was also a member the Masonic Judenlodge.[49] Heine also made he acquaintances in Berlin, of Karl August Varnhagen and his Jewish wife, and a friend of Henriette Herz, the famous salonnière Rahel. Heine was also a member of the Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft des Judenthums.

Among the many causes they advocated were, separation of church and state, the raising of the political and social position of women, and the emancipation of the Jews. Explaining the motivations for the liberal German nationalism as a Frankist Jew converted to Christianity, Börne revealed:

…yes, because I was born a bondsman, I therefore love liberty more than you. Yes, because I have known slavery, I understand freedom more than you. Yes, because I was born without a fatherland my desire for a fatherland is more passionate than yours, and because my birthplace was not bigger than the Judengasse and everything behind the locked gates was a foreign country to me, therefore for me now the fatherland is more than the city, more than a territory, more than a province. For me only the very great fatherland, as far as its language extends, is enough.[50]

Under the sovereignty of the prince bishop Karl von Dalberg, an Illuminati member with connections to the Rothschilds, Börne was appointed of police actuary in the city of Frankfurt.[51] Nevertheless, Börne commented:

A wealthy Jew kisses his hand, while a poor Christian kisses the Pope's feet. The Rothschilds are assuredly nobler than their ancestor Judas Iscariot. He sold Christ for 30 small pieces of silver: the Rothschilds would buy Him, if He were for sale.[52]

Heine’s chief patron and benefactor was his uncle, the wealthy banker Salomon Heine (1767 – 1844), called “Rothschild of Hamburg,” who was among the first members of the Hamburg Temple. Heine recounted that he had been intended by his mother for a career in banking, but that he had an encounter in 1827, he met with Nathan Rothschild, “a fat Jew in Lombard Street, St. Swithin’s Lane,” with whom he wished to be an “apprentice millionaire,” but Rothschild told him he “had no talent for business.”[53] By 1834, however, Heine had struck up a very close relationship with Nathan’s brother Baron James Rothschilds, the head of the French branch of the family. In 1843, when his publisher Julius Campe sent him the manuscript of a highly critical history of the Rothschilds, the radical republican Friedrich Steinmann’s The House of Rothschild: Its History and Transactions, Heine wrote that if the manuscript were to be suppressed it would repay the service “which Rothschild has shown me for the past 12 years, as much as this can honestly be done.”[54]

Karl and Jenny Marx were married in 1843, after which they moved to Paris and befriended his distant relative, Heinrich Heine, who was a member of Young Germany. As Jewish historian Paul Johnson pointed out in his History of the Jews, Marx’s theory of history resembles the Kabbalistic theories of the Messianic Age of Shabbetai Zevi’s mentor, Nathan of Gaza.[55] One of Marx’s grandparents was Nanette Salomon Barent-Cohen, whose cousin had married Nathan Mayer Rothschild, the head of the French branch of the family. From 1850, Marx’s private secretary was Wilhelm Pieper (1826 – 1898), who from 1852-56 as a teacher for Baron Lionel Nathan Rothschild, for his second son Alfred Rothschild (1842 – 1918).[56] At the age of 21, Alfred would take up employment at the NM Rothschild Bank, and in 1868, he became a director of the Bank of England, a post he held for 20 years, until 1889.

Hess, an influential proponent of socialism, collaborated with a number of radical philosophers associated with Marx and Engels, including P.J. Proudhon, Bruno Bauer, Etienne Cabet, Max Stiner, Ferdinand Lassalle and the Luciferian and anarchist Mikhail Bakunin.[57] Hess also befriended the “ingenious, prophetic Heine,” as he called him in his unpublished diary of 1836.[58] Hess was an enthusiastic supporter of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809 – 1865) the first political philosopher to call himself an anarchist, marking the formal birth of anarchism in the mid-nineteenth century.[59] As Jeffrey Burton Russel explains, Satan was a political symbol for the anarchists, and as an example, quotes Proudhon saying, “Come, Satan, you who have been defamed by priests and kings, that I may kiss you and hold you against my breast.”[60] Proudhon himself claimed to have been initiated in 1847 into the Masonic lodge in Besançon, Sincérité, Parfaite Union et Constante Amitié. [61] Proudhon’s best-known assertion is that “property is theft!,” contained in his first major work, What Is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government (1840). The book attracted the attention of Karl Marx, who started a correspondence with Proudhon. Ferdinand Lassalle (1825 – 1864), whose father was Heyman Lassal was a Jewish silk merchant, was a Prussian-German socialist and highly active in the Revolutions of 1848, during which he befriended Marx. Heine wrote of Lassalle in 1846: “I have found in no one so much passion and clearness of intellect united in action. You have good right to be audacious – we others only usurp this divine right, this heavenly privilege.”[62]

Buonarroti and Louis-Auguste Blanqui (1805 – 1881), also a member of the Carbonari, influenced the early French labor and socialist movements.[63] In May 1839, a Blanquist-inspired uprising took place in Paris, in which participated the League of the Just, forerunners of Karl Marx’s Communist League. In 1847, Blanqui founded the Democratic Association for the Unification of All Countries (DAUAC) as a propaganda organization. Historians describe the DAUAC as a “masonic-carbonari association.”[64] It was co-founded by the Carbonari and the German League of the Outlaws, which in turn became the League of the Just and then the Communist League of Marx and Engels. Marx was its vice-president.[65]

A founding member of the League was Jenny Marx’s brother, Edgar von Westphalen (1819 – 1890), was an early member of the Communist Correspondence Committee’s Brussels’ circle. Marx’s wife was Jenny von Westphalen, whose brother, Ferdinand von Westphalen (1799 – 1876), was the head of the Prussian secret police. Jenny was born into a family from Northern Germany that had been elevated into the petty nobility. Her paternal grandfather, Philipp Westphalen, had been ennobled in 1764 as Edler von Westphalen by Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick—Grand Master of the Strict Observance and member of the Illuminati and the Asiatic Brethren—for his military services, and had served as his de facto “chief of staff” during the Seven Years’ War.[66] Philipp’s wife Jane Wishart of Pittarrow was the descendant of many Scottish and European noble families. Jenny’s father was Philipp’s son, Ludwig von Westphalen (1770 – 1842), who befriended Marx’s father Heinrich. Ludwig became a mentor to the young Karl, introducing him to Homer, Shakespeare—who remained his favorite authors all his life—Voltaire and Racine. It was also Ludwig who first introduced Marx to the teachings of the socialist theorist Saint-Simon (1760 – 1825).[67]

First International

In 1847, the Communist League asked Marx to write The Communist Manifesto, written jointly with Engels, which was first published on February 21, 1848. In France, as the government of the National Constituent Assembly continued to resist them, the radicals began to protest against it. On May 15, 1848, Parisian workers invaded the Assembly and proclaimed a new Provisional Government. This attempted revolution was quickly suppressed by the National Guard. The leaders of this revolt, including Louis Auguste Blanqui, Armand Barbès, François Vincent Raspail and others, were arrested. In France in 1848, King Louis Philippe, the son of Philippe “Égalité,” was overthrown and the revolution of Louis Blanc (1811 – 1882) established the French Second Republic, headed by Napoleon’s nephew, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte (1808 – 1873). Blanc, one of the leading representatives of the Order of Memphis, was one of the organizers of its Supreme Council in London, where he was able to direct its policy and to influence the policy of the Lodge of the Philadelphians without officially becoming a member.[68] Two Jews were active in the French provisional government, Adolphe Crémieux and Michel Goudchaux (1797 – 1862), who was twice Minister of Finance. However, Crémieux, who held the important post of Minister of Justice, soon resigned to act as counsel for Louis Blanc, in his defense against the government.[69]

According to his friend Alexander Herzen (1812 – 1870), the “father of Russian Socialism,” Mazzini was the “shining star” of the Revolutions of 1848, when Europe experienced a series of protests, rebellions and often violent upheavals, in the Netherlands, Italy, the Austrian Empire, and the states of the German Confederation. The revolutions were inspired by ideals of “democracy,” referring to the replacement an electorate of property-owners with universal male suffrage, and “liberalism,” calling for the consent of the governed, separation of church and state, republican government, freedom of the press and the individual.

The 1840s, these ideals had been popularized by radical liberal publications such as Rheinische Zeitung (1842); Le National and La Réforme (1843) in France; Ignaz Kuranda’s Grenzboten (1841) in Austria; Lajos Kossuth’s Pesti Hírlap (1841) in Hungary, as well as the increased popularity of the older Morgenbladet in Norway and the Aftonbladet in Sweden. La Réforme was founded in 1843 by Alexandre Ledru-Rollin (1807 – 1874), a member of Carbonari. Its regular contributors included the radicals Louis Blanc, and Proudhon, Marx, and Mikhail Bakunin (1814 – 1876) also published articles. The editor was Ferdinand Flocon (1800 – 1866), also with the Carbonari, who was one of the founding members of the Provisional Government at the start of the French Second Republic. It was the speeches of Ledru-Rollin and Louis Blanc at working-men’s banquets in Lille, Dijon and Chalons that heralded the revolution of 1848.

The Rheinische Zeitung was launched in 1842, with Moses Hess serving as an editor, with Heinrich Heine as Paris correspondent, and with contributions from Karl Marx.[70] When it was evident that the newspaper was becoming bankrupt soon, George Jung (1814 – 1886) and Hess convinced some leading rich liberals of the Rhineland to establish a company to buy out the newspaper, including Gottfried Ludolf Camphausen (1803 – 1890), the Prime Minister of Prussia, Gustav von Mevissen (1815 – 1899), a leading representative of Rhineland liberalism, and Dagobert Oppenheim (1809 – 1889), the son of Salomon Oppenheim, Jr. (1772 – 1828), the scion of an illustrious family of “Court Jews” who had served as advisers and moneylenders to the Prince-Archbishops of Cologne in the Rhineland area for several generations.[71] Engels, later affirmed that it was Marx’s journalism at the Rheinische Zeitung which led him “from pure politics to economic relationships and so to socialism.”[72] After the suppression of the paper by Prussian state censorship in March 1843, Marx had left Germany, landing in Paris, and would spend the next five years in France, Belgium, and England. Marx would return to Germany in early 1848, and immediately began to make preparations to establish a new and more radical newspaper, Neue Rheinische Zeitung, one of the most important dailies of the Revolutions of 1848 in Germany.

In 1849, Hungarian Mason Lajos Kossuth (1802 – 1894) issued the celebrated Hungarian Declaration of Independence from the Habsburg Monarchy during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, and he was appointed regent-president. However, in response to the intervention of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, who was an opponent of revolution, and the failure of appeals to the western powers, Kossuth abdicated. Kossuth then first fled to the Ottoman Empire and finally arrived in England in 1851. After his arrival, the press characterized the atmosphere of the streets of London as this: “It had seemed like a coronation day of Kings.”[73] Many leading British politicians tried without success to suppress the so-called “Kossuth mania.” Palmerston intended to receive Kossuth, but it was prevented by a vote in Cabinet. Instead, Palmerston received a delegation of Trade Unionists from Islington and Finsbury and listened sympathetically as they read an address that praised Kossuth and declared the Emperors of Austria and Russia “despots, tyrants and odious assassins.”[74] That, together with Palmerston’s support of Louis Napoleon, caused the fall of the government of Lord John Russell (1792 – 1878).[75]

According to Kossuth, “The genus of Rothschilds has done more for the spread of socialism than its most passionate sectarians.”[76] In a speech he delivered in the Citizens’ Banquet in Philadelphia, December 26, 1951, he asserted.

I am no Socialist, no Communist; and if I get the means to act efficiently, I shall so act that the inevitable revolution may not subvert the rights of property: but so much I confidently declare—that to the spreading of Communist doctrines in certain quarters of Europe nobody has so much contributed as those European capitalists, who by incessantly aiding the despots with their money have inspired many of the oppressed with the belief that financial wealth is dangerous to the freedom of the world. Rothschild is the most efficient apostle of Communism.[77]

As a period of harsh reaction followed the widespread Revolutions of 1848, the next major phase of revolutionary activity began almost twenty years later with the founding of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA), often called the First International, in 1864. As demonstrated by Boris I. Nicolaevsky, the creation of the First International was the result of the efforts of the Philadelphes of the Rite of Memphis, who had become supporters of Mazzini and Garibaldi.[78] The Grand Lodge of the Philadelphians, brought together primarily, but not exclusively, by French émigrés in England, was formally part of an association that, at the beginning of the 1850’s, was known as the radical and revolutionary Order of Memphis, with members such as Mazzini, Garibaldi, and Louis Blanc. They instituted a Grand Lodge des Philadelphes, which linked up with the Carbonari, Buonarroti’s Carbonari, Mazzini’s Young Europe and were active in the founding of the Commune Révolutionnaire and the First International.[79]

In 1864, Marx obtained control of the two-year-old First International, by which a number of secret societies were absorbed.[80] The First International eventually split between two main tendencies: the state socialist wing represented by Marx and the anarchist wing represented by Mikhail Bakunin, a Grand Orient Freemason, and an avowed Satanist.[81] Bakunin, explained Boris I. Nicolaevsky, was connected to the Philadelphes.[82] Although 33º Mason of the Scottish Rite, Bakunin wrote to Herzen that he did not take Freemasonry seriously, other than it “can be useful as a mask or as a passport.”[83] Sociologist Marcel Stoetzler argued that the antisemitic trope of Jewish world domination was at the center of Bakunin’s political thought.[84] In 1869, Bakunin wrote his Polémique contre les Juifs (“Polemic Against the Jews”) mainly directed against the Jews of the International. Bakunin described as “the most formidable sect” in Europe, and asserted that a leak of information had taken place in the secret societies, and that it was the reason for the breakup of his own secret society.[85]

Le Peril Juif

The claim of a leak of secrets was also reported by Gougenot Des Mousseaux, who, also in 1969, published Le Juif, le Judaïsme et la Judaïsation des Peuples Chrétiens (“The Jews, Judaism, and the Judaification of Christian People”), with particular emphasis on the Alliance Israëlite Universelle and “universal” Freemasonry, “sharing a single life, and animated by the same soul.” According to Des Mousseaux, “It is important enough to repeat,” he wrote, “that the elite of the [Masonic] Order, the real leaders who are only known by a few initiates, and then only under assumed names, work in a profitable and secret dependence on Israelite kabbalists.” Due to the “mysterious constitution” of Freemasonry, its “sovereign counsel” consists of “a majority of Jewish members.” Adolphe Crémieux, the founder and leader of the Alliance, was Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of France and of the Rite of Misraïm. Maurice Joly, a member of Crémieux’s Misraïm lodge, was the author of Dialogues aux Enfers entre Machiavel et Montesquieu, an attack on the despotism of Napoleon III published in 1864, which is widely accepted as having been the source plagiarized to produce the Protocols of Zion.[86]

Joly’s work also supposedly as inspiration for Hermann Goedsche (1815 – 1878) to write his novel Biarritz, published in 1668, which is also believed to be a source for The Protocols.[87] In 1848, Goedsche worked for the Kreuzzeitung, a conservative newspaper whose founders included Otto von Bismarck and Friedrich Julius Stahl (1802 – 1861), a German-Jewish constitutional lawyer and philosopher associated with Schelling. The chapter “At the Jewish Cemetery in Prague” described a secret rabbinical cabal, Council of Representatives of The Twelve Tribes of Israel, which meets in the cemetery of Prague at midnight for one of their centennial meetings, to plot world domination. The chapter closely resembles a scene in Alexandre Dumas’ The Queen’s Necklace, published in 1848, where Cagliostro, chief of the Unknown Superiors, among whom are Swedenborg, arranges the Affair of the Diamond Necklace, a scandal involving Queen Marie Antoinette, which contributed to the French Revolution of 1789.[88] Goedsche appears as a character The Prague Cemetery by Umberto Eco, whose protagonist is named Simone Simonini.

At the meeting, described by Goedsche as the Fifth Sanhedrin, what is known as “The Rabbi’s Speech” is delivered, next to the tomb of the Great Master of Kabbalah, Simeon ben Yehuda, where their true god, the Golden Calf of Genesis, appears to them amidst a blue flame. He announces to those assembled that, “The day when we shall have made ourselves the sole possessors of all the gold in the world, the real power will be in our hands, and then the promises which were made to Abraham will be fulfilled.” Celebrating the power of these Jewish conspirators, he adds:

Thus, in Paris, London, Vienna, Berlin, Amsterdam, Hamburg, Rome, Naples, etc., and in all the Rothschild branches everywhere the Jews are the financial masters, simply by possessing so many milliards;… Today all reigning emperors, kings, and princes are burdened with debts contracted in keeping up large standing armies to support their toppling thrones. The stock exchange assesses and regulates those debts, and to a great extent we are masters of the stock exchange everywhere.[89]

Among the methods to achieve their goal are the acquisition of landed property, infiltration into the fields of philosophy, medicine, law, economy and high public offices, including the Church, as well as branches of science, of art, of literature. Jews are to be encouraged to take Christian wives and mistresses. Most important is control of the second power after gold: the press, to define public morality and undermine Christianity by “using the allurements of the passions as our weapon, we shall declare open war on everything that people respect and venerate.” According to the Rabbi, alluding to the Communist movement:

It is in our interest that we should at least make a show of zeal for the social questions of the moment, especially for improving the lot of the workers, but in reality our efforts must be geared to getting control of this movement of public opinion and directing it.[90]

A year after Joly’s work was published, Des Mousseaux related in Le Juif, that he had received a letter from a German statesman stating:

Since the revolutionary recrudescence of 1848, I have had relations with a Jew who, from vanity, betrayed the secret of the secret societies with which he had been associated, and who warned me eight or ten days beforehand of all the revolutions which were about to break out at any point of Europe. I owe to him the unshakeable conviction that all these movements of “oppressed peoples,” etc., etc., are devised by half a dozen individuals, who give their orders to the secret societies of all Europe. The ground is absolutely mined beneath our feet, and the Jews provide a large contingent of these miners…[91]

Bakunin’s anti-Semitism was expressed in his “To the Companions of the Federation of International Sections of Jura.” The Jura Federation represented the anarchist, Bakuninist faction formed during infighting in the First International between Bakunin and Marx’s factions. According to Bakunin:

At bottom the Jews of every country are really friends only with the Jews of all countries, regardless of all the differences which may exist between their social positions, their degrees of education, their political opinions and their religious cults. It is no longer the superstitious worship of Jehovah that constitutes the Jew today; a baptized Jew is no less a Jew. There are Catholic, Protestant, pantheistic and atheistic Jews, reactionary, liberal, even democrats and socialists. Above all they are Jews, and this establishes between all the individuals of this singular race, across all the religious, political and social oppositions, an indissoluble mutual union and solidarity—It is a powerful chain, at once broadly cosmopolitan and narrowly national, in the sense of race, which links the kings of the Bank, the Rothschilds, or the most scientifically elevated intelligences, with the ignorant and superstitious Jews of Lithuania, Hungary, Romania, Africa and Asia. I do not think there is a Jew in the world today who does not flinch with hope and pride when he hears the sacred name of the Rothschilds.[92]

Nevertheless, Bakunin notes that the Jews are “one of the most intelligent races on earth,” and cites as examples: Spinoza, Moses Mendelssohn, his son Felix and his friend Meyerbeer, Heine, Börne and even Karl Marx. However, according to Bakunin, “But, beside these great minds, there is the small fry: an innumerable crowd of little Jews, bankers, usurers, industrialists, merchants, literati, journalists, politicians, socialists and speculators always.”[93] Among them Bakunin was referring to Moses Hess and his circle inside the First International, who had suspected him of being a Russian spy. In 1871, Moses Hess was a member of the First International in the camp of Marx’s supporters. Bakunin attacked Hess as a member of Marx’s camp, which he branded a “synagogue.” Bakunin called Hess “a Jewish pygmy in Marx’s entourage” and claimed that “All the Jewish world, which is one gang of exploiters, a people of leeches, a glued-on parasite that does nothing but guzzle, transcending not only political borders but all differences of political opinion—this Jewish world stands today on one side at the orders of Marx and on the other side of the orders of Rothschild.”[94]

Italian Unification

Another work that appeared claiming to expose a Jewish conspiracy, was The Permanent Instruction of the Alta Vendita. The document, which was supposedly originally produced by the Italian Carbonari, was written by Piccolo Tigre (“Little Tiger”), and first published by Jacques Crétineau-Joly, in his book L’Église romaine en face de la Révolution in 1859. In 1846, Crétineau-Joly had met personally with Pope Pius IX who gave him a number of documents on the Alta Vendita, the highest lodge of the Carbonari, including seized correspondence, and asked him to write a history of secret societies.[95] Monsignor George F. Dillon, in his 1885 book the War of Anti-Christ with the Church and Christian Civilization, claimed that the author “Piccolo Tigre” was supposedly the pseudonym of a Jewish Freemason. According to the Permanent Instructions of the Alta Vendita:

Ever since we have established ourselves as a body of action, and that order has commenced to reign in the bosom of the most distant lodge, as in that one nearest the centre of action, there is one thought which has profoundly occupied the men who aspire to universal regeneration. That is the thought of the enfranchisement of Italy, from which must one day come the enfranchisement of the entire world, the fraternal republic, and the harmony of humanity.[96]

Dillon reported that, as communicated by Major-General Burnaby MP to the Jesuit Reverend Sir Christopher Bellew, when Cavour and Palmerston determined the moment opportune, they unleashed the Italian Revolution in conjunction with the Masonic lodges. With Italy then a hodge-podge of states, Mazzini led a revolt in 1848 against the “despotic” and “theocratic” regime of the Pope in central Italy. In March 1849, a constituent assembly abolished the temporal authority of the papacy and proclaimed the Roman Republic. However, France, under the leadership of Louis-Napoleon, quickly organized a military intervention, crushing Mazzini’s political experiment in Rome and reinstated the pope. After the failure of the Mazzini’s 1848 revolution, Garibaldi took the leadership of the Italian nationalists who began to look to the Kingdom of Sardinia as the leaders of the unification movement. After a short and disastrous renewal of the war with Austria in 1849, Charles Albert abdicated in 1849 in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel II. In 1852, a liberal ministry under Count of Cavour, was installed and the Kingdom of Sardinia became the key source of support driving Italian unification. A constitution had been conceded to the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1848, which finally became the Kingdom of a united Italy in 1861, after much of the Papal State’ territory was conquered, with Victor Emmanuel II as king.

However, following the unification of most of Italy, tensions between the monarchists and republicans erupted. Garibaldi was finally arrested for challenging Cavour’s leadership, setting off worldwide controversy. In 1866, Otto von Bismarck and Victor Emmanuel II formed an alliance with the Kingdom of Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War. In exchange, Prussia would allow Italy to annex Austrian-controlled Venice. When King Emmanuel agreed, the Third Italian War of Independence broke out. Though Italy fared poorly in the war against Austria, Prussia’s victory allowed Italy to annex Venice.

Between 1864 and 1870, Prussia, led by Otto von Bismarck, a purported leader of the Palladian Rite, fought three campaigns, including the Second Schleswig, the Austro-Prussian and the Franco-Prussian war, at the end of which it was able to consolidate the different parts of Germany under the Prussian crown. The Franco-Prussian War, which had begun in 1870, between the Second French Empire of Napoleon III and the German states of the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia, under Otto von Bismarck. To keep the large Prussian Army at bay, France abandoned its positions in Rome, which protected the remnants of the Papal States and Pius IX, in order to fight the Prussians. Italy benefited from Prussia’s victory against France by being able to take over the Papal States from French authority. Rome was captured by the kingdom of Italy after several battles against official troops of the papacy. Italian unification was completed, and shortly afterward Italy’s capital was moved to Rome.

[1] Robison. Proofs of a Conspiracy (1798), p. 115.

[2] Niall Ferguson. The Ascent of Money (Penguin, 2012), p. 86.

[3] Ibid., p. 90.

[4] Ferguson. The House of Rothschild.

[5] Norman Cohn. Warrant for genocide: the myth of the Jewish world-conspiracy and the Protocols of the elders of Zion (London: Serif, 2005), p. 32.

[6] Ibid., p. 31.

[7] Marsha Keith Schuchard. “Falk, Samuel Jacob.” In Wouter J. Hanegraaff (ed.) Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism (Leiden: Brill, 2006). p. 357.

[8] Norman Cohn. Warrant for genocide: the myth of the Jewish world-conspiracy and the Protocols of the elders of Zion (London: Serif, 2005), p. 32.

[9] Reinhard Markner. “Giovanni Battista Simonini: Shards from the Disputed Life of an Italian Anti-Semite.” In Kesarevo Kesarju. Scritti in onore di Cesare G. De Michelis, a cura di Marina Ciccarini, Nicoletta Marcialis, Giorgio Ziffer (Firenze University Press), p. 312.

[10] George F. Dillon. War of Anti-Christ with the Church and Christian Civilization (M.H. Gill & Son, 1885).

[11] John Vennari. The Permanent Instructions of the Alta Vendita (Rockford, Ill: Tan Books, 1999), p. 6.

[12] “Giuseppe Mazzini” in Volume III K – P of 10,000 Famous Freemasons, William R. Denslow, 1957, Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply Co., Inc.; Garibaldi—the mason Translated from Giuseppe Garibaldi Massone by the Grand Orient of Italy.

[13] Entry of January 23, 1904. In Marvin Lowenthal (ed. and trans.), The Diaries of Theodor Herzl (London, 1958, pp, 425–426; cited in Robert S. Wistrichin. “Theodor Herzl: Between Myth and Messianism,” in Mark H. Gelber & Vivian Liska (eds.), Theodor Herzl: From Europe to Zion (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag 2007), p. 19.

[14] Stefano Recchia & Nadia Urbinati (eds.). A Cosmopolitanism of Nations: Giuseppe Mazzini's Writings on Democracy, Nation Building, and International Relations (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), p. 1.

[15] Ibid., p. 2.

[16] Massimo Introvigne. Satanism: A Social History (Leiden: Brill, 2016), p. 217.

[17] Ibid., p. 185–186.

[18] John C. Lester & Daniel Love Wilson, Ku Klux klan: its origin, growth and disbandment, p. 27, [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=2j4OAAAAIAAJ&q=Pike]

[19] Margiotta. Adriano Lemmi, p. 97; cited in Queenborough. Occult Theocracy, pp. 225.

[20] Claus Oberhauser. “Simonini’s letter: the 19th century text that influenced antisemitic conspiracy theories about the Illuminati.” The Conversation (March 31, 2020). Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/simoninis-letter-the-19th-century-text-that-influenced-antisemitic-conspiracy-theories-about-the-illuminati-134635

[21] Mario Rossi. “Emancipation of the Jews in Italy.” Jewish Social Studies 15, no. 2 (1953), p. 119–120. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4465154

[22] Ibid.

[23] R. John Rath. “The Carbonari: Their Origins, Initiation Rites, and Aims.” The American Historical Review, 69: 2 (January, 1964), p. 355.

[24] Elizabeth L. Eisenstein. The First Professional Revolutionist: Filippo Michele Buonarroti (1761-1837) (Harvard University Press, 1959), p. 11.

[25] Melanson. Perfectibilists.

[26] Cited in Melanson. Perfectibilists.

[27] Lehning, op. cit., p. 114; cited in Melanson. Perfectibilists.

[28] “Philalèthes” Encyclopédie de la franc-maçonnerie, pocketbook, p.658, 659

[29] Wit von Dörring. Fragmente aus meinem Leben, 33-34. Cited in Rath. “The Carbonari: Their Origins, Initiation Rites, and Aims,” p. 363.

[30] Melanson. Perfectibilists.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Arthur Lehning. “Buonarroti: And His International Secret Societies.” International Review of Social History, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1956), p. 120.

[36] Wit von Dörring. Fragmente aus meinem Leben, 33-34. Cited in Rath. “The Carbonari: Their Origins, Initiation Rites, and Aims,” p. 363.

[37] Melanson. Perfectibilists.

[38] Eisenstein. The First Professional Revolutionist, p. 88.

[39] Monsignor George Dillon. Grand Orient Freemasonry Unmasked (London: Britons Publishing Company, 1950) p. 89.

[40] Billington. Fire in the Minds of Men, p. 137

[41] “Freemasonry, Secret Societies, and the Continuity of the Occult Tradition in English Literature.” Ph.D. diss., (Austin: University of Texas, 1975) p. 353; “Yeats and the Unknown Superiors: Swedenborg, Falk, and Cagliostro,” Hermetic Journal, 37 (1987) p. 18; Schuchard. “Dr. Samuel Jacob Falk,” p. 217.

[42] Clark Marvin H., Jr. Karl Marx: Prophet of the Red Horseman.

[43] Ferguson. The House of Rothschild.

[44] Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels. The Holy Family.

[45] Benjamin Peixotto. “Principality, now Kingdom, of Roumania.” Menorah Vol. I. JULY, 1886 No. 1. p. 345.

[46] Edmund Silberner. “Zwei unbekannte Briefe von Moses Hess an Heinrich Heine.” International Review of Social History, 6, 3 (1961), p. 456.

[47] David Bakan. Sigmund Freud and The Jewish Mystical Tradition (Princeton University Press, 1958), p. 196.

[48] Ibid., p. 196.

[49] Katz. Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723-1939, p. 82.

[50] Ludwig Börne. Gesammelte Schriften, vol. V (Milwaukee, 1858) p. 31-32; cited in Adolf Kober. “Jews in the Revolution of 1848 in Germany.” Jewish Social Studies, 10, no. 2 (1948), p. 137.

[51] Hugh Chisholm (ed.). “Börne, Karl Ludwig.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4, 11th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1911), pp. 255–256.

[52] Gerald Posner. God’s Bankers: A History of Money and Power at the Vatican (Simon and Schuster, 2015), p. 12.

[53] Ferguson. The House of Rothschild.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Paul Johnson. A History of the Jews (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987). p 348.

[56] “The Knight of Noble Consciousness.” Volume 12 (New York, 1854), p. 479

[57] Nahum Norbert Glatzer. The Judaic Tradition: Texts (Behrman House Inc., 1969) p. 526.

[58] Edmund Silberner. “Zwei unbekannte Briefe von Moses Hess an Heinrich Heine.” International Review of Social History, 6, 3 (1961), p. 456.

[59] Isaiah Berlin. The Life and Opinions of Moses Hess (Jewish Historical Society of England, 1959), p. 21.

[60] Jeffrey Burton Russell. Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World (Ithica: Cornell University Press, 1986), p. 234.

[61] Denis William Brogan. Proudhon (London: H. Hamilton, 1934), chap. iv. Retrieved from https://www.freemasonry.bcy.ca/history/revolution/index.html#14

[62] W.H. Dawson. German Socialism and Ferdinand Lassalle (London: Swan Sonnenschein, 1891), p. 115.

[63] Thomas Kurian (ed). The Encyclopedia of Political Science (Washington D.C: CQ Press, 2011. p. 1555.

[64] E. J. Hobsbawm. The Age of Revolution 1789 -1948 (N.Y.: 1964), p. 157-160.

[65] Gallante Garone. Buonarroti e i rivoluzionari (1951), p. 400-09.

[66] Boris I Nicolaevsky & Otto Maenchen-Helfen. Karl Marx: man and fighter (Taylor & Francis, 1973), pp. 22–27.

[67] Ibid., pp. 22–27.

[68] Eisenstein. The First Professional Revolutionist, pp. 43-4; Melanson. Perfectibilists.

[69] Henry Samuel Morais. Eminent Israelites of the Nineteenth Century: A Series of Biographical Sketches (E. Stern & Company, 1879), p. 36.

[70] Adolf Kober. “Jews in the Revolution of 1848 in Germany.” Jewish Social Studies, 10: 2 (1948), p. 138.

[71] David Mclellan. Karl Marx: A Biography. Fourth ed. (Palgrave Macmillan, 1981), pp. 38–39.

[72] “Frederick Engels to R. Fischer,” cited in David McLellan. Karl Marx: His Life and Thought (New York: Harper and Row, 1973), p. 57.

[73] Phineas Camp Headley. The Life of Louis Kossuth: Governor of Hungary (Publisher: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1856), p. 241.

[74] Jasper Ridley. Lord Palmerston (Publisher Pan Macmillan, 2013).

[75] Laurence Fenton. Palmerston and the Times: Foreign Policy, the Press and Public Opinion in Mid-Victorian Britain (I.B.Tauris, 2012), pp. 119–20.

[76] Lajos Kossuth. “Speech at Buffalo.” Select Speeches of Kossuth (ed.) Francis William Newman (2004). Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/10691/pg10691.html

[77] Lajos Kossuth. “Speech at the Citizens' Banquet, Philadelphia, Dec. 26th.” Select Speeches of Kossuth (ed.) Francis William Newman (2004). Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/10691/pg10691.html

[78] Boris I. Nicolaevsky. “Secret Societies and the First International.” The Revolutionary Internationals, 1864-1943; ed. Milorad M. Drachovitch, (Stanford University Press, 1966).

[79] Ibid.

[80] Nesta H. Webster. World Revolution Or the Plot Against Civilization (Kessinger Publishing) p. 187.

[81] Ibid.

[82] Nicolaevsky & Maenchen-Helfen. Karl Marx, pp. 22–27.

[83] T.R. Ravindranathan. Bakunin & the Italians (Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988), pp. 26

[84] Marcel Stoetzler. Antisemitism and the Constitution of Sociology (University of Nebraska Press, 2014) , pp. 139–140.

[85] James Guillaume. Documents de l’Internationale, I. 131. Cited in Nesta Webster. Secret Societies and Subversive Movements. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19104/19104-h/19104-h.htm

[86] Lord Alfred Douglas. Plain English (1921); Kerry Bolton, The Protocols of Zion in Context, 1st Edition, (Renaissance Press: Paraparaumu Beach, 2013).

[87] Paul R Mendes-Flohr & Jehuda Reinharz. The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History (Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 363 see footnote.

[88] Binjamin W. Segel, Richard S. Levy, (ed.). A Lie and a Libel: The History of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion (University of Nebraska Press, 1996), p. 97,

[89] Cohn. Warrant for genocide, p. 280.

[90] Ibid., p. 284.

[91] Gougenot des Mousseaux. Le Juif, le Judaïsme et la Judaïsation des Peuples Chrétiens (2nd edition, 1886), pp. 367, 368.

[92] Mikhail Bakunin. Translation of the antisemitic section of Bakunin's "Letter to Comrades of the Jura Federation.” Retrieved from https://libcom.org/article/translation-antisemitic-section-bakunins-letter-comrades-jura-federation

[93] Ibid.

[94] Alex Gordon. “Moses Hess: The Red Rabbi.” San Diego Jewish World (March 16, 2023); Michael Robert Marrus. “The Origins of the Holocaust.” (Walter de Gruyter, 2011), p. 226.

[95] Robert De Mattei. Pius IX (Gracewing, 2004), p. 3.

[96] Dillon. Grand Orient Freemasonry Unmasked, p. 89

Zionism

Introduction

Kings of Jerusalem

The Knight Swan

The Rose of Sharon

The Renaissance & Reformation

The Mason Word

Alchemical Wedding

The Invisible College

The New Atlantis

The Zoharists

The Illuminati

The American Revolution

The Asiatic Brethren

Neoclassicism

Weimar Classicism

The Aryan Myth

Dark Romanticism

The Salonnières

Haskalah

The Carbonari

The Vormärz

Young America

Reform Judaism

Grand Opera

Gesamtkunstwerk

The Bayreuther Kreis

Anti-Semitism

Theosophy

Secret Germany

The Society of Zion

Self-Hatred

Zionism

Jack the Ripper

The Protocols of Zion

The Promised Land

The League of Nations

Weimar Republic

Aryan Christ

The Führer

Kulturstaat

Modernism

The Conservative Revolution

The Forte Kreis

The Frankfurt School

The Brotherhood of Death

Degenerate Art

The Final Solution

Vichy France

European Union

Eretz Israel