3. Zionism

Star of David

The main accomplishment of World War I was to free the land of Palestine from Ottoman control, contributing towards the establishment of the State of Israel, a long-standing objective of the Zionists. World War I was precipitated when the Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. The three chief assassins were Gavrilo Princip and two of his friends, who were all members of a nationalist group called the Order of the Black Hand, a secret society that had been founded in 1911 as the Union of Death to fight for Serbian liberation. The seal of the order was a clenched fist holding a skull and crossbones beside a knife, a bomb and a poison bottle.[1] The involvement of the Russians was purportedly exposed when it was discovered that a secret payment of eight thousand rubles had been given to the Black Hand leader by the Russian military attaché in Belgrade. The order had apparently been accompanied by a promise from Tsar Nicholas II, knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, that he would support Serbia in the event of war breaking out between Russian and the Austro-Hungarian empire. It was also rumored that representatives of the Black Hand had met with several members of the French Grand Orient at the Hotel St. Jerome in Toulouse in January of that year. One of the topics allegedly discussed was the murder of the emperor Franz Joseph and the archduke Ferdinand.[2]

The Zionist movement was founded by Theodor Herzl—a former member of the German nationalist Burschenschaft (fraternity) Albia—who Anti-Zionist rabbis and other Jewish opponents often compared Herzl disparagingly with Shabbetai Zevi, who declared himself the Messiah in 1666.[3] The Sabbatean influences on the Zionist movement are demonstrated by its rejection of Jewish law, while also adhering to the expectations of the Messiah, whose arrival is expected to initiate the return of all Jews dispersed in the Diaspora to the Promised Land. In “Herzl’s Image and the Messianic Idea,” Arthur Kamczycki explained that, “From the very beginning Zionism opposed the conservative rabbinate and the religious Jewry in general.”[4] According to orthodox interpretation, the restoration of Zion by the Messiah could not be brought about through a human whose actions would be subject to God’s will.[5] Additionally, attempts at estimating the time of the Messiah’s arrival were seen as blasphemy. Herzl, who was aware of this discrepancy, stated that “the orthodoxy should understand that there is no contradiction between God’s will and the Zionist attempt of grabbing the destiny with one’s own hands.”[6]

After World War I, the British Government would cede the territory of Palestine to Zionist colonization, as outlined in the Balfour Declaration, written by Lord Balfour (1848 – 1930) with the assistance of Weizmann to Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild (1868 – 1937), who had inherited the title of baron from his father, Nathan “Natty” Rothschild (1840 – 1915), head of the English branch of the family founded by his father, Nathan Mayer Rothschild. Before placing their hopes in Britain, the German Zionists had first turned to Germany, hoping their German imperialism would provide a protectorate in Palestine for Jewish settlement.[7] Herzl first attempted to recruit Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany (1859 – 1941), to influence Abdul Hamid II (1842 – 1918), a fellow knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, to seriously consider the proposals of the Zionists. In Istanbul, in 1896, with the assistance of Count Philip Michael von Nevlinski, a Polish émigré with political contacts in the Ottoman Court, Herzl attempted to meet the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II (1842 – 1918), a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, in order to present his proposition of a Jewish State to him directly. He failed to obtain an audience but did succeed in visiting a number of highly placed individuals, including the Grand Vizier.

Genealogy of the House of Rothschild

Mayer Amschel Rothschild (built fortune as banker to William I, Elector of Hesse, brother of Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, member of Illuminati and Grand Master of the Asiatic Brethren)

Amschel "Anselm" Mayer Rothschild (1773–1855, Frankfurt branch. Died childless, his brothers assumed responsibility for the business from 1855)

Salomon Mayer von Rothschild (1774–1855, Austrian branch, retained ties with Prince Metternich, whose father, Franz Metternich (1746 – 1818), had been a member of the Illuminati)

Anselm Salomon von Rothschild (1803 – 1874) + Charlotte Nathan Rothschild

Nathaniel Meyer von Rothschild (1836 – 1905, in homosexual relationship with Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg, close friend of friend of Kaiser Wilhelm II, knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, who shared his interest in the occult. Eulenburg summoned Theodor Herzl to Liebenberg to announce that Wilhelm II wanted to see a Jewish state established in Palestine)

Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777–1836, London branch, founder of N. M. Rothschild & Sons) + Hannah Barent-Cohen (sister of wife of Moses Montefiore, Freemason who founded Alliance Israëlite Universelle with Benjamin Disraeli and Adolphe Crémieux, member of Memphis-Mizraim and Grand Commander of the Grand Lodge of France)

Lionel Nathan (1808–1879) + Charlotte von Rothschild (cousin of Nanette Salomon Barent-Cohen, grandmother of Karl Marx)

Baron Lionel de Rothschild (1808 – 1879, friend of Benjamin Disraeli) + Charlotte von Rothschild

Baron Nathan “Natty” Rothschild (1840 – 1915, friend of Cecil Rhodes and funded founding of the Round Table. Friend of Lord Randolph Churchill (1849 –1895), father of Winston Churchill. Friend of Prince of Wales, father of Prince Albert Victor (1864 – 1892), who had an illegitimate child with Mary Jean Kelly, whose friends numbered among Jack the Ripper’s victims) + Emma Louise von Rothschild

Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild (1868 – 1937, close friend of Weizmann, who helped to draft the Balfour Declaration presented to him, written by Round Table member Lord Balfour, along with the help of Louis Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter and Rabbi Stephen Wise, all leading Zionists and known Sabbateans)

Alfred Rothschild (1842 – 1918, tutored by Wilhelm Pieper, Karl Marx’s private secretary. Friend of Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII. Friend of Round Table member, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener (1850 – 1916), who Lanz von Liebenfels claimed was a member of his Order of New Templars (ONT) and a reader of his anti-Semitic magazine Ostara, a magazine avidly ready by a young Hitler) + Marie Boyer

Leopold de Rothschild (1845 – 1917) + Marie Perugia

Lionel de Rothschild (1882 – 1942, close friend of Winston Churchill) + Marie Louise Eugénie Beer

Calmann "Carl" Mayer Rothschild (1788–1855, Naples branch)

James Mayer de Rothschild (1792–1868, Paris branch, patron of Rossini, Chopin, Balzac, Delacroix, and Heinrich Heine)

Alphonse James de Rothschild (1827 – 1905)

Edmond James de Rothschild (1845 – 1934, supporter of Zionism, his large donations lent significant support to the movement during its early years, which helped lead to the establishment of the State of Israel. In Jerusalem, Theodor Herzl and Kaiser Wilhelm II met at Mikveh Israel, a village and boarding school, founded in 1870 by Charles Netter, an emissary of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, with Baron Edmond James de Rothschild contributing)

Banker and politician Nathan “Natty” Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild (1840 – 1915) and his brother Leopold de Rothschild (1845 – 1917)

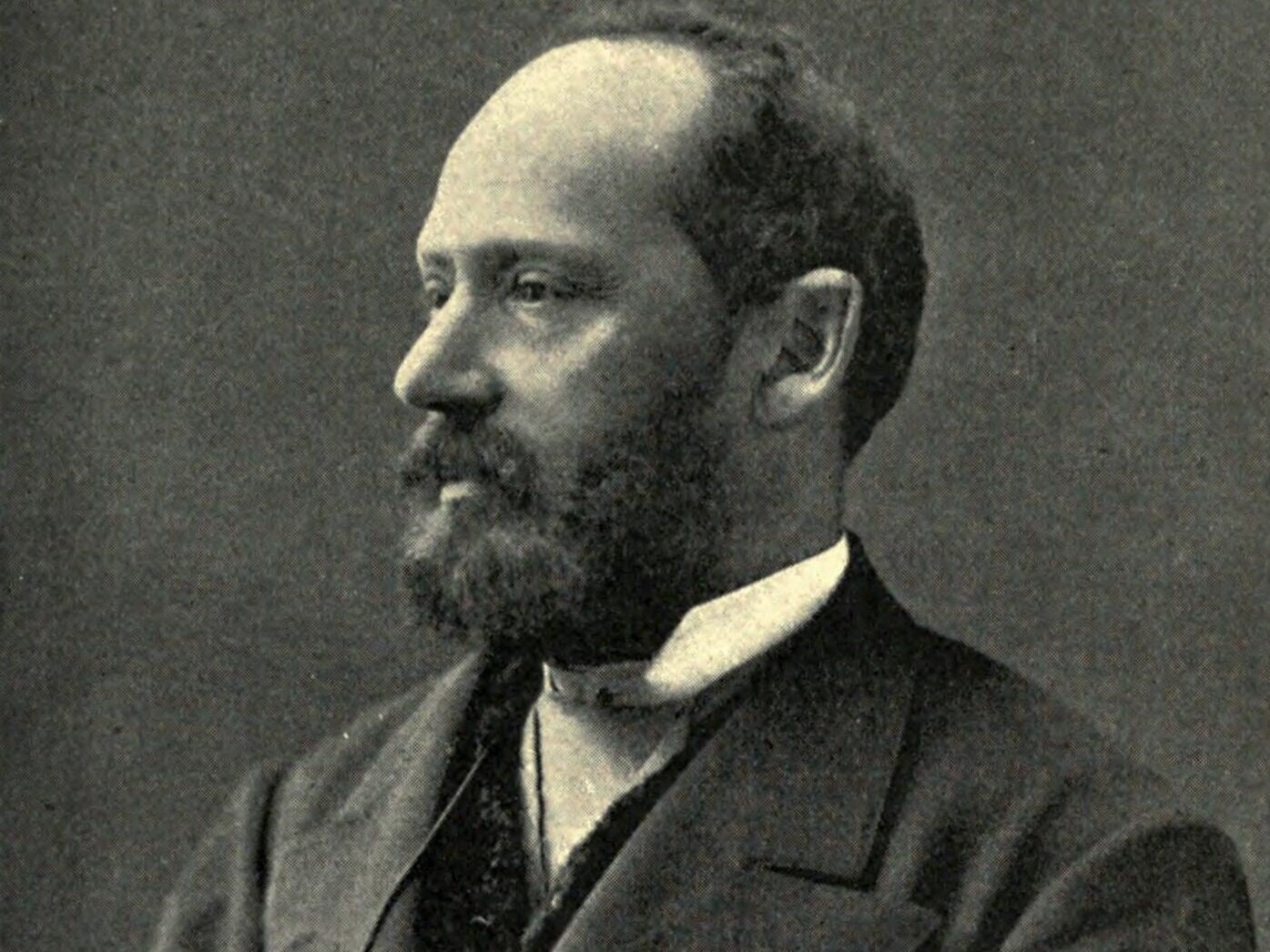

Chaim Weizmann (1874 – 1952), President of the World Zionist Organization and first President of Israel

Having failed to gain the support of either the Kaiser or the Sultan, Herzl turned to Great Britain in 1900, joining the pro-British Zionist faction that was soon to be led by Chaim Weizmann (1874 – 1952), President of the World Zionist Organization (WZO), who helped draft the Balfour Declaration, and later first President of Israel. Weizmann was a great admirer of Nietzsche, and sent Nietzsche’s books to his wife, adding a comment in a letter that “This was the best and finest thing I can send to you.”[8] At the time, World War I was referred to as “Nietzsche in Action,” or the “Euro-Nietzschean (or Anglo-Nietzschean) War.”[9] By World War I, Nietzsche had acquired a reputation as an inspiration for both right-wing German militarism and leftist politics.[10] During the Dreyfus affair the French antisemitic Right also labelled the Jewish and leftist intellectuals who defended Dreyfus as “Nietzscheans.”[11] Nietzsche had a distinct appeal for many Zionist thinkers around the start of the twentieth century, most notable being Ahad Ha’am, Hillel Zeitlin, Micha Josef Berdyczewski, A.D. Gordon and Martin Buber, who went so far as to extoll Nietzsche as a “creator” and “emissary of life.”[12]

In light of the pogroms in Russia and the Dreyfus Affair in France, Herzl argued that the best way to avoid anti-Semitism in Europe was to create an independent Jewish state. First written as a pamphlet and published in 1896, Herzl’s Der Judenstaat (“The Jewish State”) is considered one of the most important texts of early Zionism. Herzl argued that the Jewish people should leave Europe for Palestine, as their only opportunity to avoid anti-Semitism, express their culture freely and practice their religion without hindrance. Herzl’s ambitions were reflected in a similar conclusion drawn in Rome and Jerusalem (1862) by Moses Hess, in Rome and Jerusalem (1862), who had taught communism to Karl Marx. Herzl was also inspired by both Spinoza and Moses Hess. Herzl’s diary entry reads, “So, I was captivated and elated by him [Moses Hess]. What a high, noble spirit. Everything that we tried he had already written… Judaism hasn’t produced a greater mind since Spinoza than this forgotten, faded Moses Hess!”[13] Herzl ended his diary entry with the toast of the B’nai B’rith “Fiducit!”

Herzl’s book was subtitled Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage (“Proposal of a modern solution for the Jewish question”) and was originally called “Address to the Rothschilds,” as Herzl planned to deliver it as a speech to the Rothschild family. Herzl appealed to the nobility of Jewish England—the Rothschilds, Sir Samuel Montagu, later cabinet minister, to the Chief Rabbis of France and Vienna, the railroad magnate, Baron Hirsch. In preparatory notes for his appeal to the Jewish philanthropist Baron Hirsch to underwrite the Jewish State, Herzl concluded his request with the words “Honor, Freedom, Fatherland,” the old Albia motto.[14] Herzl travelled to Paris in 1896 to meet with Baron Edmond de Rothschild (1845 – 1934), the son of James Mayer de Rothschild, founder of the French branch of the Rothschild dynasty. Edmond was a well-known benefactor and patron of the new settlement in Palestine. The Baron rejected Herzl’s request to raise money for the realization of his plan, feeling that it threatened Jews in the Diaspora. He also thought it would put his own settlements at risk.[15] Nevertheless, the Baron became a strong supporter of Zionism, his large donations lent significant support to the movement during its early years, which helped lead to the establishment of the State of Israel.

However, Herzl decided to act alone without the help of wealthy Jews. In 1897, at considerable personal expense, Herzl founded the Zionist newspaper Die Welt in Vienna, and planned the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. He was elected president of the Congress, a position he held until his death in 1904. In 1898, he began a series of diplomatic initiatives to build support for a Jewish country. He was received by Wilhelm II on several occasions, one of them in Jerusalem, and in 1899 he attended The Hague Peace Conference, called by Tsar Nicholas II, where Herzl was interviewed by its chief organizer, the journalist W.T Stead, a friend of Blavatsky, Annie Besant and involved in the occult circle around Papus who were responsible for the forgery of the Protocols of Zion.[16]

Theodor Herzl on a white donkey in Jerusalem, evoking the iconographic tradition the Messiah who is often portrayed as a man on a white horse, mule or donkey, usually entering the city.

Victor Emmanuel III of Italy (1869 – 1947), the grandson of Victor Emmanuel II, who succeeded in becoming king of a united Italy through his participation in the conspiracy of the Carbonari headed by Giuseppe Mazzini, revealed that one of his ancestors had been a co-conspirator of Shabbetai Zevi.

During a two-week trip to Italy in 1904, Herzl met with Pope Pius X in an effort to gain his support for the cause of Zionism. The meeting occurred two days after Herzl had met with Victor Emmanuel III of Italy (1869 – 1947), the grandson of Victor Emmanuel II, who succeeded in becoming king of a united Italy through his participation in the conspiracy of the Carbonari headed by Giuseppe Mazzini. In addition to showing an interest in the Zionist movement, Victor Emmanuel III revealed that one of his ancestors had been a co-conspirator of the false Messiah Shabbetai Zevi. When the king asked Herzl if there were still Jews who expected the Messiah, Herzl assured him: “Naturally, Your Majesty, among religious circles. In our own, the university-trained and enlightened classes, no such thought exists […] our movement has a purely national character.”[17] Herzl mentioned to the king that while visiting Jerusalem, he did not want to use a white horse, mule or donkey in order to avoid evoking the iconographic tradition of the Messiah who is often portrayed as a man on a white horse, mule or donkey, usually entering the city. Nevertheless, in the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem are two photographs showing Herzl riding on the back of a white donkey.[18]

A few months before meeting Victor Emmanuel III, Herzl was warned by Dr. Joseph Samuel Bloch, editor of the Österreichische Wochenschrift, that if he were to present himself as the Messiah, that all Jews would reject him Instead, he told Herzl, “The Messiah must remain a veiled, hidden figure.”[19] Nevertheless, in “Theodor Herzl: Between Myth and Messianism,” Robert S. Wistrichin pointed out, “Yet his diaries testify that from June 1895 (when his Zionist conversion is usually dated) his curiosity and even sense of affinity with Shabbetai Zevi was growing.”[20] Herzl wrote in a diary entry from March 1896: “the difference between myself and Sabbatai Zevi, or the way I perceive him… is that Zevi became so great that he equaled the greats of this world, whereas I belong to the little ones of this world.”[21] In Herzl’s utopian novel Old-New Land (1902), the protagonists are presented with the choice of spending an evening at a theatrical performance, a drama about Moses, or an opera about Zevi, they choose the opera. The novel’s protagonist David Littwak, while watching the opera, explains the success of false leaders:

It was not that the people believed what these charlatans told them, but the other way round—they told them what they wanted to believe. They satisfied a deep longing. That is it. The longing brings forth the Messiah. You must remember what miserable dark ages they were, the times of Sabbatai and his like. Our people were not yet able to gauge their own strength, so they were fascinated by the spell these men cast over them. Only later, at the end of the nineteenth century when all the other civilized nations had already gained their national pride and acted accordingly - only then did our people, the pariah among the nations, realize that they could expect nothing from fantastic miracle-workers, but everything from their own strength.[22]

Page of segulot in a mediaeval Kabbalistic grimoire (Sefer Raziel HaMalakh, thirteenth century)

According to Gershom Scholem, and later Jacqueline Rose as outlined in The Question of Zion, Zionism derived from Sabbateanism.[23] Herzl’s appeals fared best with Israel Zangwill (1864 – 1926), and Max Nordau (1849 – 1923), co-founder of the World Zionist Organization (WZO) together with Herzl at the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897. Zangwill, who earned the nickname “the Dickens of the Ghetto,” wrote an internationally successful novel Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People (1892). Zangwill’s Dreamers of the Ghetto (1898) consists of a series of sketches based on the lives of historical figures, including Benjamin Disraeli, Heinrich Heine, Ferdinand Lassalle, Spinoza, and a glowing account of the mission of Shabbetai Zevi.

The six-pointed Star of David became representative of the worldwide Zionist community after it was chosen as the central symbol on a flag at the First Zionist Congress in 1897. Modern interpretations attributed the use of the symbol to the influence of the Zohar through Isaac Luria who identified it with the “Primal Man and the world of Emanations.”[24] However, as Scholem pointed out, the six-pointed star is not a true Jewish symbol, but is a magical talisman associated with the magic of the practical Kabbalah, also known as the Seal of Solomon.[25] The earliest identification of the symbol with David is found in the Book of Desire, which is an interpretation of the seventy magical names of Metatron, Prince of the Divine Presence, by Eleazar of Worms or one of his disciples.[26] Until the seventeenth century, the five-pointed pentagram and the six-pointed stars were called by one name, the “Seal of Solomon,” but slowly the Star of David becomes applicable only to the six-pointed star. The official use of the Star of David began in Prague and spread out from there to Moravia and Austria. It was through the influence of the crypto-Sabbatean Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz, that the Star of David finally became a messianic symbol.[27] In the nineteenth century, the new emancipated Jews sought a unique symbol to identify themselves, chose the Star of David for its lack of specifically religious connotations, when the symbol finally became widely adopted.

Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise (1874–1949)

The “reluctant father of American Zionism” was Columbia professor Richard Gottheil. Gottheil’s father, Gustav Gottheil (1827 – 1903), eventually became the chief Rabbi and one of the most influential, well-known and controversial leaders in America of Reform Judaism—a Sabbatean movement—and in 1897, he was the most prominent American to attend the first Zionist Congress in Basel. In 1897, Richard Gottheil founded the Federation of American Zionist Societies of New York (FAZ), an amalgam of Jewish societies that all endorsed the Basel program of the First Zionist Congress. FAZ established The Maccabean, the first English language Zionist magazine, edited by Louis Lipsky, who would later become the voice for later the Zionist Organization of America.[28] From 1898 to 1904, Gottheil was president of the American Federation of Zionists, and worked with both Stephen S. Wise (1874 – 1949), who became FAZ’s secretary. Helen Rawlinson in her book Stranger At The Party, recounts a sexual encounter where she describes how Wise had sex with her in his office on his conference table, and quoted the verse from Psalms which Sabbateans did when engaged in sexual intercourse.[29] Gottheil attended the second Zionist Congress in Basel of 1897, establishing relationships with Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau.[30] Rabbi Wise attended as the American correspondent for William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal.

Herzl recommended to Gottheil that he hire Jacob de De Haas, the secretary of the First Zionist Congress, who became the new secretary of FAZ. De Haas befriended later U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Dembitz Brandeis (1856 – 1941), whom he introduced to the ideas of Herzl and ideals of Zionism, and who would later assist Chaim Weizmann in formulating the Balfour Declaration. Brandeis belonged to a Frankist family, being descended from Esther Frankel, an aunt of Rabbi Zecharias Frankel, a Sabbatean and intellectual progenitor of Conservative Judaism.[31] Brandeis, would head the FAZ and the American Zionist movement by 1912. Brandeis was head of world Zionism when the war forced the movement to relocate its headquarters to New York from Berlin. Under Brandeis’ leadership, the American Zionist movement grew from 10,000 members to over 200,000 members by 1920.

Brandeis encouraged Felix Frankfurter to become more involved in Zionism.[32] Frankfurter received a portrait of Jacob Frank’s daughter Eva from his mother, a tradition among Sabbateans.[33] During World War I, Frankfurter served as Judge Advocate General. After the war, he helped found the American Civil Liberties Union and returned to his position as professor at Harvard Law School. He became a friend and adviser of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who appointed him to the Supreme Court, where he served from 1939 to 1962. According to Frankfurter, “The real rulers in Washington are invisible and exercise their power from behind the scenes.”[34]

Brandeis, Frankfurter, Wise and others laid the groundwork for a democratically elected nationwide organization of “ardently Zionist” Jews, “to represent Jews as a group and not as individuals.”[35] In 1918, following national elections, this Jewish community convened the first American Jewish Congress (AJC). Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, Felix Frankfurter, Louis Brandeis, and others joined to lay the groundwork for a national democratic organization of Jewish leaders from all over the country, to rally for equal rights for all Americans regardless of race, religion, or national ancestry.[36] Rabbi Wise remained the President and chief spokesperson of the AJC until his death in 1949.

Dispensationalism

John Nelson Darby (1800 – 1882), influential figure of the Plymouth Brethren, the same sect to which Aleister Crowley’s family belonged

Important in exploiting Britain for its ambitions, Zionism made use of Sabbatean millenarianism, as expressed in an interpretation of the End Times known as Dispensationalism, which developed from Evangelical Christianity and contributed to the emergence of Christian Zionism. The origins of Evangelicals are usually traced to 1738, with various theological streams contributing to its foundation, including English Methodism, Count Zinzendorf’s Moravian Church, and German Lutheran Pietism.[37] In addition to influencing leaders and major figures of the Evangelical Protestant movement, such as English Puritans John Wesley, George Whitefield, and Jonathan Edwards of the Great Awakenings in England and the United States, the Moravian Church was also responsible for another Evangelical sect, the Plymouth Brethren, the same sect that Aleister Crowley was raised in.[38]

John Nelson Darby (1800 – 1882), one of the Plymouth Brethren’s influential figures, devised the system of dispensationalism that was incorporated in the development of modern Evangelicalism, and which reflected the millenarian aspirations of Sabbateanism. As a hint of their probable crypto-Judaism, Christian dispensationalists sometimes embrace what some critics have pejoratively called “Judeophilia,” which includes support of the state of Israel, observing traditional Jewish holidays and practicing traditionally Jewish religious rituals.[39] Dispensationalist beliefs are at the forefront of Christian Zionism, which shares the exact same ambitions of the Zionists, but instead when God has fulfilled his promises to the nation of Israel, the future world to come will result in a millennial kingdom and Third Temple where Christ, upon his return, will rule the world from Jerusalem for a thousand years.

Most early nineteenth-century British Restorationists, like Charles Simeon (1759 – 1836), were Postmillennial in eschatology, an interpretation of chapter 20 of the Book of Revelation which sees Christ’s second coming as occurring after the Millennium.[40] In 1809, leading evangelical Anglicans such as Simeon and William Wilberforce—leader of the Clapham sect and the great champion of the abolition of slavery—who desired to promote Christianity among the Jews, formed the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews. The society’s work began among the poor Jewish immigrants in the East End of London and soon spread to Europe, South America, Africa and Palestine.[41] It supported the creation of the post of Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem in 1841, and the first incumbent was one of its workers, Michael Solomon Alexander (1799 – 1845), a former rabbi who converted to Christianity from Judaism.[42] The Protestant Bishopric in Jerusalem was formed in that same year when the British and Prussian Governments as well as the Church of England and the Evangelical Church in Prussia entered into a unique agreement. The Prussian Union of Churches was a major Protestant church body which emerged in 1817 from a series of decrees by Frederick William III of Prussia that united both Lutheran and Reformed denominations in Prussia. Frederick’s father was Frederick William II, who belonged to the Golden and Rosy Cross and fell under the influence of two other members, who also belonged to the Asiatic Brethren, Johann Christoph von Wöllner and Johann Rudolf von Bischoffwerder.[43] It was with the Emancipation Edict of 1812 that the Jews in the Prussian territory succeeded in obtaining equal rights from Frederick William III.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847), grandson of Illumitus Moses Mendelssohn, successor of Sabbatai Zevi

Prussian Union of Churches became the largest independent religious organization in the German Empire and later Weimar Germany. Karl Marx’s father, Heinrich Marx (1777 – 1838), known as a child as Herschel, converted from Judaism to join the state Evangelical Church of Prussia, taking on the German forename Heinrich over the Yiddish Herschel.[44] In 1816, at the age of seven years, the grandson of Illuminati member Moses Mendelssohn, the composer Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847), was baptized with his brother and sisters in a home ceremony by Johann Jakob Stegemann, minister of the Evangelical congregation of Berlin’s Jerusalem Church and New Church.[45] Although Mendelssohn was a conforming Christian as a member of the Reformed Church, he was both conscious and proud of his Jewish ancestry and notably of his connection with his grandfather Moses.[46] In 1843, Mendelssohn accepted a leadership position as Generalmusikdirektor at the Belin Cathedral, a central institution of the Prussian Union Church, and he composed numerous pieces of music for use in the service.[47]

In 1844, George Bush, a professor of Hebrew at New York University and the cousin of an ancestor of the Presidents Bush, published a book titled The Valley of Vision; or, The Dry Bones of Israel Revived, in which he called for “elevating” the Jews “to a rank of honorable repute among the nations of the earth” by allowing restoring them to the land of Israel where the bulk would be converted to Christianity. This, according to Bush, would benefit not only the Jews, but all of mankind, forming a “link of communication” between humanity and God. “It will blaze in notoriety…” He added, “It will flash a splendid demonstration upon all kindreds and tongues of the truth.”[48]

Quatuor Coronati

1898 Masonic degree conferred in 'Solomon's Quarry' (Zedekiah’s Cave) below the Temple Mount in Jerusalem

Lord Shaftesbury (1801 – 1885), member of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF)—which had sponsored the first Masonic lodge in Palestine

When Wilberforce died in 1833, one of those who attended his funeral was Lord Shaftesbury (1801 – 1885), who was one of the first leading Christian Zionists. Shaftesbury was a member of the Canterbury Association, as were two of Wilberforce’s sons, Samuel and Robert. Lewis Carrol, author of Alice in Wonderland, was ordained by Samuel Wilberforce, then Bishop of Oxford. Shaftesbury married Lady Emily Caroline Catherine Frances Cowper, who was likely to have been the natural daughter of Lord Palmerston (later her official stepfather), in 1830. Shaftesbury was an early proponent of the Restoration of the Jews to the Holy Land, providing the first proposal by a major politician to resettle Jews in Palestine.

In 1875, Shaftesbury told the Annual General Meeting of the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF)—who had sponsored the first Masonic lodge in Palestine—that “We have there a land teeming with fertility and rich in history, but almost without an inhabitant—a country without a people, and look! scattered over the world, a people without a country,” being one of the earliest usages by a prominent politician of the phrase “A land without a people for a people without a land,” which was to become widely used by Zionists.[49]

The PEF was linked to Quatuor Coronati (QC) Lodge, a Masonic Lodge in London dedicated to Masonic research, to the Golden Dawn and the murders of Jack the Ripper. The PEF was founded in 1865, shortly after the completion of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem, and is the oldest known organization in the world created specifically for the study of the region of Palestine. The Ordnance Survey, the first scientific mapping of Jerusalem, was undertaken by Charles William Wilson, an officer in the Royal Engineers corps of the British Army, and with the sanction of the Secretary of State for War, George Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon (1827 – 1909). Lord Ripon was a Freemason, who served as Provincial Grand Master of the West Riding and Deputy Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England from 1861 to 1869, and ultimately as Grand Master from 1870 until 1874.[50] In 1874, Wilson became a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Lieutenant Charles Warren (1840 – 1927), Freemason and member of the Palestine Exploration Fund who discovered Templar tunnels beneath the Temple of Jerusalem.

In 1867, PEF’s biggest expedition was headed by General Sir Charles Warren (1840 – 1927) along with Captain Wilson and a team of Royal Engineers, who discovered Templar tunnels beneath the ancient Temple of Jerusalem in 1867.[51] Warren named his find the “Masonic Hall.”[52] Warren was also supportive of bringing Freemasonry to the Holy Land. PEF members were involved in the first Masonic meeting in Palestine was held on May 7, 1873, within the cave known as Solomon’s Quarries.[53]

Warren was the founding Master of the Quatuor Coronati (QC) Lodge, founded in 1886, and who meet at Freemasons Hall in London. Rev. A.F.A. Woodford (1821 – 1887), a fellow founder of the QC Lodge, was Grand Chaplain of United Grand Lodge. The legendary Cypher Manuscript of the Golden Dawn was in Woodford’s possession in 1886 and he gave it to his friend Wynn Westcott in 1887, resulting in the establishment of the Golden Dawn. Another QC founder, Robert Freke Gould (1836 – 1915), was initiated in the Gibraltar Lodge in 1857, and was succeeded as Worshipful Master by George Francis Irwin. It was at Gibraltar that Irwin first met Warren, who was initiated there in 1859. Gould also recalled that Warren had a great respect for Irwin, both as a Freemason and a soldier.[54]

Annie Besant’s brother-in-law, Sir Walter Besant (1836 – 1901), was an enthusiastic Freemason, becoming the third District Grand Master of the Eastern Archipelago in Singapore, one of the founding members of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge and was acting secretary of the PEF, between 1868 and 1887. Walter Besant’s main novels included All in a Garden Fair, which Rudyard Kipling credited in Something of Myself with inspiring him to leave India and make a career as a writer.[55] Walter Besant also co-authored the novel The Monks of Thelema (1878) with James Rice. In 1883, he was also made a Knight of Justice of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, and in 1884 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Field Marshal Lord Kitchener (1850 – 1916), who Ariosophist Lanz von Liebenfels claimed was a member of his Order of New Templars (ONT) and a reader of his anti-Semitic magazine Ostara.

An important member of the PEF was Field Marshal Lord Kitchener (1850 – 1916), who Lanz von Liebenfels claimed was a member of his Order of New Templars (ONT) and a reader of his anti-Semitic magazine Ostara.[56] Nevertheless, Kitchener was also a close friend of Alfred de Rothschild (1842 – 1918), who was tutored as a child by Karl Marx’s private secretary Wilhelm Pieper, and who took up employment at the N.M. Rothschild Bank in London, headed by his brother Nathan Rothschild, and became a director of the Bank of England, a post he held for twenty years, until 1889. Kitchener was commissioned into the Royal Engineers in 1871, and in 1874 he was assigned by the PEF to a mapping-survey of the Holy Land. Kitchener was credited in 1898 for winning the Battle of Omdurman, against Abdullah al-Taashi, the successor to the self-proclaimed “Mahdi,” Muhammad Ahmad, and securing British control of the Sudan. As Chief of Staff in the Second Boer War, Kitchener won notoriety for his imperial campaigns, most especially his scorched earth policy against the Boers and his expansion of Lord Roberts’ internment camps. After a term as Commander-in-Chief (1902–09) in India, Kitchener then returned to Egypt as British Agent and Consul-General (de facto administrator). While in Egypt, Kitchener was initiated into Freemasonry in 1883 in the Italian-speaking La Concordia Lodge No. 1226. In 1899, he was appointed the first District Grand Master of the District Grand Lodge of Egypt and the Sudan, under the United Grand Lodge of England.[57] Kitchener later played a central role in the early part of World War I.

Jack the Ripper

Jack the Ripper murders took place in the predominantly Jewish disctrict of Whitechapel, close to the Rothschild Buildings, and were covered up by Captain Warren of the Palestine Exploration Fund

From 1886 to 1888, Warren became the chief of the London Metropolitan Police during the Jack the Ripper murders. Jack the Ripper was an unidentified serial killer active in the largely impoverished areas in and around the Whitechapel district of London in 1888. All the murders took place within the distance of a few streets, late at night or in the early morning, and the victims were all women whose throats were cut. In four of the cases, their bodies were mutilated, or even eviscerated. The removal of internal organs from three of the victims led to contemporary proposals that “considerable anatomical knowledge was displayed by the murderer, which would seem to indicate that his occupation was that of a butcher or a surgeon.”[58] Five victims—Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes, and Mary Jane Kelly—whose murders took place between August 31 and November 9, 1888, are known as the “canonical five.”

According to author Stephen Senise, in Jewbaiter Jack The Ripper: New Evidence & Theory, it is not a coincidence that Britain’s most infamous unsolved crime is alleged to have been committed by a Jew, but were designed to tap that most ancient of anti-Semitic slanders, the “blood libel.” The murders took place in Whitechapel, a poverty-stricken slum in London’s East End and its surrounding neighborhoods almost exclusively Jewish, famously portrayed in Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto. In Dickens’ Oliver Twist, the den operated by Fagin, “the Jew” and ringleader of the boy thieves, was located in Whitechapel. Whitechapel was at the center of the huge late nineteenth century influx of Jewish immigration into Britain. In many parts of the East End, Jews constituted a majority of the local population. Sunday Magazine labeled the area “the Jewish colony in London.”[59]

Baron Nathan Rothschild remarked, “…We have now a new Poland on our hands in East London. Our first business is to humanise our Jewish immigrants and then to Anglicise them”[60] In 1885, Nathan Rothschild founded the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company, with of other prominent, Jewish philanthropists including Frederick Mocatta and Samuel Montagu, the MP of Whitechapel, to provide “the industrial classes with commodious and healthy Dwellings at a minimum rent.”[61] The company set out to replace the lodging houses of Whitechapel with tenements, known as “Rothschild Buildings,” designed to house mostly Jewish tenants on Thrawl Street, Flower and Dean Street, and George Street in Spitalfields, just outside the City of London.[62] Flower and Dean Street was one of the most notorious slums of the Victorian era, being described in 1883 as “perhaps the foulest and most dangerous street in the whole metropolis.”[63]

The “canonical five” were all associated with the Flower and Dean Street neighborhood.[64] Both Mary Jane Kelly and Patty Nichols were living on Thrawl Street. Annie Chapman had been well-known throughout Spitalfields. Elizabeth Strive was staying at 32 Flower and Dean, opposite the Rothschild Buildings. Eddowes lived with her common law husband John Kelly at Cooney’s common lodging-house at 55 Flower and Dean Street.[65] A description of Jack the Ripper was given by George Hutchinson, an unemployed laborer who knew Kelly, and reported to have met her in the early hours of November 9 on Flower and Dean Street who asked him for money. Hutchinson stated that as Kelly walked in the direction of Thrawl Street she was approached by a man of “Jewish appearance” and aged about 34 or 35. Hutchinson claimed he was suspicious of this man because, although Kelly seemed to know him, this individual's opulent appearance made him a suspicious character to be in the neighborhood.[66]

Since the murder of Mary Ann Nichols, rumors had been circulating that the killings were the work of a Jew dubbed “Leather Apron,” which had resulted in antisemitic demonstrations. In both the criminal case files and contemporary journalistic accounts, the killer was called the Whitechapel Murderer and Leather Apron. The name may be an allusion to the ceremonial aprons of Freemasonry, which were originally made of leather.[67] One Jew, John Pizer, who had a reputation for violence against prostitutes and was nicknamed “Leather Apron” from his trade as a bootmaker, was arrested but released after his alibis for the murders were corroborated.[68] Pizer had a prior conviction for a stabbing offence, and Police Sergeant William Thicke apparently believed that he had committed a string of minor assaults on prostitutes.[69]

Russell Edwards in Naming Jack the Ripper claims that the murderer was Aaron Kosminski, a Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe. Kosminski had been one of the key suspects in the murders, but police did not have enough evidence to convict him. From 1891, Kosminski was institutionalized after he threatened a woman with a knife. He was first held at Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum, and then transferred to the Leavesden Asylum. Dr. Jari Louhelainen, a leading expert in genetic evidence from historical crime scenes and a senior lecturer in molecular biology at Liverpool John Moores University, assisted Edwards in finding the DNA evidence connecting Kosminski to the Eddowes murder. In March 2019, the Journal of Forensic Sciences published a study conducted by scientists at Liverpool John Moores University and the University of Leeds, stated in its conclusion that the DNA evidence on the shawl matched the female victim and derived from blood and semen stains is that of Kosminski.[70]

Masonic ritual reeacting “the three rufians” known as the “Juwes”

The murder scenes were all in close proximity to Jewish establishments. Buck’s Row was opposite Brady Street Ashkenazi Cemetery; on Hanbury Street was Glory of Israel and Sons of Klatsk Synagogue; on Berner Street was St. George’s Settlement Synagogue; and Mitre Square, where Catherine Eddowes was murdered, was beside the Great Synagogue; and Miller’s Court was beside Spitalfields Great Synagogue.[71] After the murders of Stride and Eddowes in the early morning hours of September 30, Constable Alfred Long of the Metropolitan Police Force discovered a dirty, bloodstained piece of an apron in the stairwell of a tenement on Goulston Street in Whitechapel, most of whose residents were Jews.[72] Goulston Street was within a quarter of an hour’s walk from Mitre Square, on a direct route to Flower and Dean Street where Eddowes lived. The cloth was later confirmed as being a part of the apron worn by Eddowes. Above it, there was writing in white chalk on either the wall or the black brick jamb of the entranceway, with the words, “the Juwes are the men that Will not be Blamed for nothing.” This graffito became known as the Goulston Street graffito.

In their book The Ripper File, Elyn Jones and John Lloyd noted that the word “Juwes” was actually a Masonic reference. In the ritual of Master Mason, Hiram Abif was slain by three ruffians collectively termed The Juwes. The three “Juwes” are named as Jubela, Jubelo and Jubelum and obviously have a common root in Jubel. The ordeals attributed to the three ruffians mirror the mutilations of the victims. The throats of all the Ripper victims were cut. Chapman and Eddowes had their intestines thrown over their shoulders. In testimony, when Dr. Brown, the City Police surgeon was asked to comment on his statement that the intestines were “placed,” the coroner asked “do you mean put there by design,” Brown answered in the affirmative.[73] Likewise, as Jones and Lloyd shown, the crimes are similar to the account of the three “Juwes” who lamented their fate:

Jubela: that my throat had been cut across, my tongue torn out…

Jubelo: that my left breast had been torn open and my heart and vitals taken from thence and thrown over the left shoulder….

Jubelum that my body had been severed in two in the midst, and divided to the north and south…[74]

Edward, Prince of Wales (and future Edward VII) and his wife Alexandra, Princess of Wales (third from left) and their five children. From left, Prince Albert Victor (1864 – 1892), a.k.a. Jack the Ripper; Maud, Queen of Norway; Louise, the Princess Royal, Duchess of Fife; Prince George (future George V) and Princess Victoria.

The novel Dracula, by Golden Dawn member Bram Stoker, was inspired by the serial killings of Jack the Ripper. Eerily, in a preface to Dracula, Stoker confessed that, “The strange and eerie tragedy which is portrayed here is completely true, as far as all external circumstances are concerned…”[70] The Jack the Ripper murders implicated the famous actor Henry Irving, who served as Stoker’s inspiration for the character Count Dracula.[71] Irving, the first actor to be knighted, ran the Lyceum Theatre where Stoker served as his business manager from 1878 to 1898. Irving had also been initiated into the Jerusalem Lodge of Freemasonry, which included the Prince of Wales (1841 – 1910), the son of Queen Victoria, later Edward VII King of England, who had been installed as Most Worshipful Grand Master of the Masonic Order in England in 1875.[72]

The Prince of Wales was also a close friend of Baron Nathan Rothschild. The Prince of Wales married Alexandra of Denmark, the daughter of Christian IX of Denmark and his first cousin, Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel, of the house of Hesse-Kassel who had been intimately connected with the Rothschilds and the Rosicrucians.[73] Christian IX’s grandfather was Prince Frederick of Hesse-Kassel (1747 – 1837), whose brother Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel was a friend of Comte St. Germain and a member of the Illuminati and Grand Master of the Asiatic Brethren.[74] His wife Louise was a close friend of the Polish medium Marie de Riznitch, Comtesse de Keller, who was the wife of Alexandre Saint-Yves d’Alveydre, who learned of Synarchism from Jamal ud Din al Afghani, the founder of Salafism, posing as Hajji Sharif.[75]

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (1849 – 1895), father of Sir Winston Churchill

In Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, Stephen Knight proposed that the murders were part of a Masonic coverup. When it was discovered that Prince of Wales’ son Prince Albert Victor (1864 – 1892) had an illegitimate child with Mary Jean Kelly, whose friends numbered among Jack the Ripper’s victims, they attempted to blackmail the government. Sir William Gull, Physicians-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria and a Freemason, was called in to rectify the potential scandal. Their executions were carried out in what appeared to be ritual Masonic fashion by a group drawn from Irving’s Masonic network, Lord Salisbury who was Prime Minister at the time of the murders, and included Sir William Gull, and Lord Randolph Churchill (1849 –1895), father of future Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill.[81]

Randolph Churchill was a close friend of fellow Mason, Baron Nathan Rothschild. Churchill was a descendant of the first famous member of the Churchill family, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. Churchill’s legal surname was Spencer-Churchill, as he was related to the Spencer family, though, starting with his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, his branch of the family used the name Churchill in his public life. Winston Churchill’s mother was Jennie Jerome, daughter of American Jewish millionaire Leonard Jerome.[82] Known as the “King of Wall Street,” Jerome controlled the New York Times and had an interest in a number of railway companies and was a friend of William K. Vanderbilt.[83] Through his mother’s family, several of Churchill’s ancestors had fought in the American Revolution on behalf of the American cause. As a result, in 1947, Churchill’s was admitted as a member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the State of Connecticut. Churchill, a Scottish Rite Freemason, was eventually invested as Knight of the Order of the Garter. He was also a member of the Ancient Order of Druids, created by Wentworth Little, founder of the SRIA.[84]

William T. Stead (1849 – 1912), founder of the Round Table and a friend of H.P. Blavatsky and Annie Besant, and who was part of the circle of occultists around Papus involved in forging the Protocols of Zion.

Aleister Crowley (1875 – 1947), head of the British branch of the Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO)

However, acting as Police Commissioner, Warren feared that the Goulston Street graffito might spark anti-Semitic riots and ordered the writing washed away before dawn.[85] While most historians put the police’s failure to catch the Ripper down to incompetence, as recently as 2015, a book about the case by Bruce Robinson, titled They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper, criticized Warren as a “lousy cop” and suggested that a “huge establishment cover-up” and a Masonic conspiracy had been involved.

On October 17, after noticing that Warren had been claiming that “no language or dialogue is known in which the word Jews is spelled JUWES,” Robert Donston Stephenson (1841 – 1916), a journalist and military surgeon obsessed with the occult, wrote a letter to the City Police, claiming that a similar word did indeed exist.[86] Stephenson, however, seemed to be toying with the police as he suggested the word was a misspelling of the French Juives, for “Jews.” Stephenson, who lived near the site of the murders at the time they were committed, wrote articles claiming to know the true identity of Jack the Ripper, and that the murderer would have to be a practician of “black magic,”, derived from Éliphas Lévi's work Le Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie.[87] Stephenson himself came under suspicion by the police and was arrested twice for the crimes but was released each time.

Robert Donston Stephenson (1841 – 1916), suspected by W.T. Stead and Aleister Crowley of being the real Jack the Ripper

Stephenson also later fell under the suspicion of newspaper editor W.T. Stead, a friend of Blavatsky and Annie Besant, who was part of the circle of occultists around Papus involved in forging the Protocols of Zion. In a foreword to an article written by Stephenson in the April 1896 issue of Stead’s spiritualist journal Borderland, Stead writes that the author “prefers to be known by his Hermetic name of Tautriadelta,” and that he believed him to be Jack the Ripper. In the article itself, Tautriadelta claims to have been a student occultism under Edward Bulwer-Lytton.[88] Stephenson lived in Whitechapel, in the same lodginghouse where Theosophist Mabel Collins and her occultist friend Vittoria Cremers lived. After having read the book Light on the Path by Collins, Cremers felt inspired to immediately join the Theosophical Society. In 1888, she travelled to Britain to meet Blavatsky, who asked her to take over the management of the Theosophical journal Lucifer. Cremers was soon introduced to the bisexual Mabel Collins, with whom she competed for attention with Stephenson. Cremers was also a disciple of Aleister Crowley and came to believe that Stephenson was Jack the Ripper, and that in a trunk under his bed she had found five blood-soaked ties, which had supposedly become stained as a result of his cannibalism. Accepting the story as true, Crowley came to regard Stephenson as a talented black magician, and later claimed to a member of the press that he met Stephenson who had given him the five ties.[89]

Crowley reports that during his trip to America he met a man named Henry Hall who had interviewed Stead and confirmed his own diagnosis of him: “In walking down the street, Stead broke off every minute or two to indulge in a lustful description of some passing flapper and slobber how he would like to flagellate her.”[90] Stead is mentioned in an unpublished article by Crowley, titled “Jack the Ripper,” where he recounts the story between Collins, Cremers and Stephenson. However, in his characteristically enigmatic style, Crowley began the article by stating that, “It is hardly one’s first, or even one's hundredth guess, that the Victorian worthy in the case of Jack the Ripper was no less a person than Helena Petrovna Blavatsky.” Then, he notes that “persons sufficiently eminent” in matters of occult knowledge possess an “overflowing measure the sense of irony and bitter humour” and “exercise it is notably by writing with their tongues in their cheeks, or making fools of their followers.” Crowley goes on to explain that reports of fraud attached to Blavatsky only served to get rid of doubters among her followers that she had no need of. Crowley then goes on to recount a story that Cremers turned Collins against Stephenson, which is why the searched through his things.

Crowley also mentions an article that appeared in Stead’s Pall Mall Gazette by Tau Tria Delta, which proposed that the murders followed prescriptions found in the grimoires of the Middle Ages, whereby a sorcerer could attain “the supreme black magical power,” including the power of invisibility. Additionally, the location of each murder formed the shape of an upside-down pentagram pointing South. Finally, after a discussion with a crime expert of the Empire News, Crowley decided to explore the possible astrological significance of the murders, and wrote he discovered that, in every case, either Saturn or Mercury were precisely on the Eastern horizon. As Crowley explained, “Mercury is, of course, the God of Magic, and his averse distorted image the Ape of Thoth, responsible for such evil trickery as is the heart of black magic, while Saturn is not only the cold heartlessness of age, but the magical equivalent of Saturn. He is the old god who was worshiped in the Witches’ Sabbath.”[91]

Mikveh Israel

The Zionist Delegation to the German Kaiser Wilhelm II in Smyrna (1898)

Armin Vambery (1832 – 1913)

William Hechler (1845 – 1931)

Bram Stoker’s consultant on Transylvanian culture was a close friend of Theodor Herzl, Hungarian Zionist named Arminius Vambery (1832 – 1913). Vambery was professor of Oriental languages at the University of Budapest, who had become an adviser to the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and also performed intelligence work for Lord Palmerston, the Grand Patriarch of Freemasonry.[92] Vambery also chronicled the strange vampire and other legends of the Balkans. It was through Vambery that Stoker chose the name “Dracula,” from the legend of Vlad III the Impaler, the patronym of the descendants of Vlad II Dracul of the Order of the Dragon. The character of Professor Van Helsing in Stoker’s novel Dracula is sometimes said to be based on Vambery. In chapter 23 of the novel, the professor refers to his “friend Arminius, of Buda-Pesth University.”

Vambery was a strong supporter of British expansionism and also served as foreign consultant to Abdul Hamid II. In that position, he introduced Herzl to the Sultan in 1901. In his diaries, Herzl devotes many pages to describing his encounters with Vambery and repeatedly acknowledges his contributions to the Zionist cause. While Max Nordau claims that it was he who first introduced Herzl to Vambery in 1898, Herzl identified William Hechler (1845 – 1931), an English clergyman of German descent who became a close friend of Herzl, as the one who introduced him to Vambery in 1900 in his efforts to meet with the Sultan.[93] It was also Hechler who assisted Herzl in his attempts to recruit Kaiser Wilhelm II to the Zionist cause. Hechler’s interest in Jewish studies and Palestine evolved under the influence of Restorationism, a term that was eventually replaced by Christian Zionism. He began developing his own eschatological theories and timelines for the Second Coming of Jesus Christ. In 1854, Hechler returned to London and took a position with the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews.

By 1873, Hechler became the household tutor to the children of Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden (1826 – 1907), a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. In 1856, Frederick married the grand-daughter of Frederick William III, Princess Louise, the younger sister of Frederick III and aunt of the young Hohenzollern prince, and later Kaiser Wilhelm II, also a knight of the Golden Fleece. Frederick III’s wife was Victoria, Princess Royal, the eldest child of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, also a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. As the eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria, Wilhelm was the nephew of Edward VII, Prince of Wales, and therefore cousin of Prince Albert Victor, or Jack the Ripper. His first cousins included George V of the United Kingdom and many princesses who, along with Wilhelm’s sister Sophia, became European consorts.’s

Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden (1826 – 1907)

Through Friedrich’s son Ludwig, Hechler developed a relationship with the young Wilhelm II. Hechler’s wife had been a student of one of the Kaiser’s closest friends and suspected homosexual lover Philipp Friedrich Alexander, Prince of Eulenburg and Hertefeld, Count of Sandels (1847 – 1921), a diplomat and composer of Imperial Germany who achieved considerable influence through his friendship with the Kaiser, who shared his interest in the occult.[94] Eulenburg became very close to the French diplomat, writer and racist Count Arthur de Gobineau, whom Eulenburg was later to call his “unforgettable friend.”[95] Eulenburg was deeply impressed by An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races, where Gobineau expounded the theory of an Aryan master-race and that the people who had best preserved Aryan blood were the Germans. Eulenburg later recalled how he and Gobineau had spent hours during their time in Sweden under the “Nordic sky, where the old world of the gods lived on in the customs and habits of the people as well in their hearts.”[96] Gobineau would later to write that only two people in the world who properly understood his racist philosophy were Richard Wagner and Eulenburg.[97] Eulenburg spent the rest of his life promoting racist and anti-Semitic views, writing in his 1906 book Eine Erinneruung an Graf Arthur de Gobineau (“A Memoir of Count Arthur de Gobineau”) that Gobineau was a prophet who showed Germany the way forward to national greatness in the twentieth century.

Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg (1847 – 1921)

In 1885, when the editor of the Bayreuther Blätter, the official newspaper of the Wagner cult, wrote to Eulenburg asking that he allow his letters to Gobineau to be published in the newspaper, Eulenburg wrote back to say that he could not publish his correspondence with Gobineau as their letters “…touch on so many intimate matters that I cannot extract much from them which is of general interest.”[98] Despite his anti-Semitism, during his time as Ambassador to Austria, Eulenburg engaged in a homosexual relationship with the Austrian Jewish banker Nathaniel Meyer von Rothschild (1836 – 1905), grandson of Salomon Mayer von Rothschild (1774 – 1855), founder of the Austrian branch of the family.[99] Eulenburg played an important role in the rise of Bernhard von Bülow (1849 – 1929), a German statesman and knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, who served as Foreign Minister for three years and then as Chancellor of the German Empire from 1900 to 1909, but fell from power in 1907 due to the Harden–Eulenburg affair when he was accused of homosexuality. The Harden–Eulenburg affair was the controversy in Germany surrounding a series of courts-martial and five civil trials regarding accusations of homosexual conduct, and accompanying libel trials, among prominent members of Kaiser Wilhelm II’s cabinet and entourage during 1907–1909. The affair centered on journalist Maximilian Harden’s accusations of homosexual conduct between the Eulenburg and General Kuno, Graf von Moltke. The scandal threatened Eulenburg when the wife of Kuno von Moltke, in a sealed deposition, filed for divorce on the grounds that her husband was more interested in having sex with Eulenburg than with her.[100] Moltke was forced to leave the military service.

Kaiser Wilhelm II as well was a known anti-Semite. Lamar Cecil, Wilhelm’s biographer noted that in 1888 a friend of Wilhelm “declared that the young Kaiser’s dislike of his Hebrew subjects, one rooted in a perception that they possessed an overweening influence in Germany, was so strong that it could not be overcome.” Cecil concludes:

Wilhelm never changed, and throughout his life he believed that Jews were perversely responsible, largely through their prominence in the Berlin press and in leftist political movements, for encouraging opposition to his rule. For individual Jews, ranging from rich businessmen and major art collectors to purveyors of elegant goods in Berlin stores, he had considerable esteem, but he prevented Jewish citizens from having careers in the army and the diplomatic corps and frequently used abusive language against them.[101]

Hechler’s Restorationist theology resonated with the Grand Duke, who would have a pivotal role in the history of the Zionist movement.[102] While serving as Chaplain of the British Embassy in Vienna, Hechler, who had read Herzl’s Der Judenstaat, visited Herzl in 1896. Herzl later wrote in his diary, “Next we came to the heart of the business. I said to him: I must put myself into direct and publicly known relations with a responsible or non responsible ruler—that is, with a minister of state or a prince. Then the Jews will believe in me and follow me. The most suitable personage would be the German Kaiser.”[103] Hechler arranged an extended audience with Grand Duke in 1896. The Grand Duke spoke with the Kaiser in October 1898 about the Zionists’ ideas. David Wolffsohn, the Cologne banker who was later elected to succeed Herzl after the latter’s death in 1904, reported the talk between the Grand Duke and the Kaiser: “The Kaiser was even said to have been ready to assume protectorate powers over the new state. He was said to have expressed the wish to receive a Zionist deputation in Jerusalem so that he could disclose this to it.”[104]

Hechler arranged an introduction for Herzl to Eulenburg. On October 7, 1898, Eulenburg summoned Herzl to Liebenberg to announce that Wilhelm II wanted to see a Jewish state established in Palestine (which would be a German protectorate) in order to “drain” the Jews away from Europe, and thus “purify the German race.”[105] In Berlin, Herzl had already negotiated with the German Chancellor Prince Hohenlohe, and with Eulenburg’s friend Bernard von Billow, the Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, and he believed that a Jewish state in Palestine was close at hand. Through the efforts of Hechler and the Grand Duke, Herzl publicly met Wilhelm II in 1898. The Kaiser assured Herzl of his support for the Jewish protectorate under Germany. They decided that Herzl, and his associate Max Bodenheimer, the first president of the Zionist Federation of Germany and one of the founders of the Jewish National Fund, and Wolffsohn should head for the Near East. Bodenheimer wrote:

The German ambassador in Turkey, Marshall von Bieberstein, stands... in high favour with the Sultan. Supposedly the difficulty lay in finding a form for the state which would guarantee the supreme rule of the Sultan… In a communication addressed to Count Eulenburg, the German Ambassador in Vienna, Herzl had compiled all points of view in order to move the Kaiser into taking up the cause in his hand… The return of the Jews to Palestine would bring culture and order into that neglected corner of the Orient. By means of the German protectorate we would arrive at an orderly state of affairs. In this letter, the Grand Duke reportedly informed Herzl that the Kaiser was full of enthusiasm for the cause.[106]

A week later, they met again in Jerusalem. During the trip, Herzl commissioned Bodenheimer to work on a declaration that would be presented to the Kaiser. Bodenheimer later commented:

Our imagination had been urged on unchecked on account of the extraordinary event. So following the word of God in the Bible, I demanded the land stretching between the brook of Egypt and the Euphrates, as the region for Jewish colonization. In the transitional period the land would be divided into districts which would come under Jewish administration as soon as a Jewish majority was reached.[107]

Herzl and Kaiser Wilhelm II in Mikveh Israel (1898)

In Jerusalem, Herzl and the Kaiser met at Mikveh Israel, a village and boarding school, named after the Hebrew title of Menasseh ben Israel’s Hope of Israel, published in 1650. Mikveh Israel was founded in 1870 by Charles Netter, an emissary of the Alliance Israélite Universelle. “Mikveh Israel” was Netter became the first headmaster with Baron Edmond James de Rothschild contributing to the upkeep of the school. The meeting significantly advanced Herzl’s and Zionism’s legitimacy in Jewish and world opinion. According to the London Daily Mail, “An Eastern Surprise: Important Result of the Kaiser’s Tour: Sultan and Emperor Agreed in Palestine: Benevolent Sanction Given to the Zionist Movement One of the most important results, if not the most important, of the Kaiser's visit to Palestine is the immense impetus it has given to Zionism, the movement for the return of the Jews to Palestine. The gain to this cause is the greater since it is immediate, but perhaps more important still is the wide political influence which this Imperial action is like to have. It has not been generally reported that when the Kaiser visited Constantinople, Dr. Herzl, the head of the Zionist movement, was there; again when the Kaiser entered Jerusalem, he found Dr. Herzl there. These were no mere coincidences, but the visible signs of accomplished facts.” [108]

In 1902–03, with Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain, Herzl negotiated with the Egyptian government for a charter for the settlement of the Jews in the Sinai Peninsula, but the project was blocked by Lord Cromer, the Consul General in Egypt. In 1903, Herzl attempted to obtain support for the Jewish homeland from Pope Pius X, but Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val ordained that the Church’s policy decreed that as long as the Jews denied the divinity of Christ, it could not support their cause.

In August of 1903, Herzl visited St. Petersburg and was received by Helene Blavatsky’s cousin, Sergei Witte, then finance minister, and Viacheslav Plehve, minister of the interior, to discuss a proposition that the Russian government request from the Turks a charter for Jewish colonization of Palestine. Witte was a patron of the theosophist Esper Ukhtomskii, who was part of the network of occultists in St. Petersburg who envisioned Nicholas II was the “White Tsar of Shambhala.”[109] Witte assured Herzl that he was “a friend of the Jews.”[110] In that same month, however, Plehve passed on documents to Tsar Nicholas II that suggested Witte was part of a Jewish conspiracy. As a result, Witte was removed as Minister of Finance.[111]

Plehve had organized the Kishinev pogroms of April of the same year, which focused worldwide condemnation of the persecution of Jews in Russia. The Kishinev pogrom led Herzl to advance a scheme proposed by British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain for a Jewish Colony in what is now Kenya, which became known as the “Uganda Project.” The plan was endorsed by the majority at the Sixth Zionist Congress in Basel in August, 1903, but faced strong opposition from the Russian delegation particularly, who stormed out of the meeting. In 1905, the Seventh Zionist Congress declined the offer and committed itself to a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Scofield Bible

Cyrus Scofield (center) with the Deacons of the First Congregational Church of Dallas (c. 1880s)

As the fall of the Ottoman Empire appeared to be on the horizon, the advocacy of restorationism increased. By the end of the nineteenth century, the old evangelical consensus fragmented and Protestant churches became divided over new intellectual and theological ideas, such as Darwinian evolution and historical criticism of the Bible. Those who embraced these liberal ideas became known as modernists, while those who rejected them became known as fundamentalists. Fundamentalists defended the doctrine of biblical inerrancy and adopted a dispensationalist system for interpreting the Bible.[112]

The foundations of Christian Zionism were laid when Darby visited the United States and catalyzed a new movement. This was expressed at the Niagara Bible Conference in 1878, which issued a 14-point proclamation, including the following text:

that the Lord Jesus will come in person to introduce the millennial age, when Israel shall be restored to their own land, and the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord; and that this personal and premillennial advent is the blessed hope set before us in the Gospel for which we should be constantly looking. (Luke 12:35–40; 17:26–30; 18:8 Acts 15:14–17; 2 Thess. 2:3–8; 2 Tim. 3:1–5; Titus 1:11–15)

Dispensationalist beliefs were popularized in the United States by the evangelical Cyrus Scofield (1843 – 1921). However, Scofield had a history of fraud and abandoned his wife and two daughters, perhaps in part because of his self-confessed heavy drinking.[113] Two years after Scofield’s reported conversion to Christianity in 1879, the Atchison Patriot described Scofield as “late lawyer, politician and shyster generally,” and went on to recount a few of Scofield’s “many malicious acts.” These included a series of forgeries in St. Louis, for which he was sentenced to six months in jail. As a biographer wrote, Scofield “was secretive about his past and not above distorting the facts of his shadowy years.”[114] During the early 1890s, Scofield began styling himself Rev. C.I. Scofield, D.D., but there are no extant records of any academic institution having granted him the honorary Doctor of Divinity degree. Nevertheless, when the Scofield Reference Bible was published by Oxford University Press in 1909, it quickly became the most influential statement of dispensationalism. The Scofield Bible also endorsed the curse of Ham theory.[115]

Scofield was heavily influenced by Darby, as evidenced in the explanatory notes to his Scofield Reference Bible. A core doctrine is the expectation of the Second Coming and the establishment of a Kingdom of God on Earth. Scofield further predicted that Islamic holy places would be destroyed and the Temple in Jerusalem would be rebuilt, signaling the end of the Church Age when all who seek to keep the covenant with God will acknowledge Jesus as their Messiah in defiance of the Antichrist.

William Eugene Blackstone (1841 – 1935), author of the Blackstone Memorial

In 1891, the tycoon William Eugene Blackstone, who was inspired by the Niagara Bible Conference to publish the book Jesus is Coming, had lobbied President Benjamin Harrison for the restoration of the Jews, in a petition signed by 413 prominent Americans, that became known as the Blackstone Memorial. The names included the US Chief Justice, Speaker of the House of Representatives, the Chair of the House Foreign Relations Committee, and several other congressmen, future President William McKinley, and Chief Justice Melville Fuller, John D. Rockefeller, J.P. Morgan Sr. and other famous industrialists. It read, in part: “Why shall not the powers which under the treaty of Berlin, in 1878, gave Bulgaria to the Bulgarians and Servia [Serbia]to the Servians [Serbians] now give Palestine back to the Jews?… These provinces, as well as Romania, Montenegro, and Greece, were wrested from the Turks and given to their natural owners. Does not Palestine as rightfully belong to the Jews?”[116]

Lotus Club

Nathan Straus (1848 – 1931), Louis Brandeis (1856 – 1941), Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise

Samuel Untermyer (1858 – 1940), Golden Dawn member, Satanist and active Zionist

On May 16, 1916, at the behest of Louis Brandeis, Nathan Straus (1848 – 1931)—who co-owned two of New York City’s biggest department stores, R.H. Macy & Company and Abraham & Straus—wrote Rev. Blackstone:

Mr. Brandeis is perfectly infatuated with the work that you have done along the lines of Zionism. It would have done your heart good to have heard him assert what a valuable contribution to the cause your document is. In fact he agrees with me that you are the Father of Zionism, as your work antedates Herzl.[117]

Brandeis recruited C.I. Scofield after he joined the prestigious Lotos Club in New York. Founded primarily by a young group of writers and critics, the club was composed of journalists, artists, musicians, actors and amateurs of literature, science and fine arts. Mark Twain, an early member, called it the “Ace of Clubs.” The Club took its name from “The Lotos-Eaters,” a poem by Tennyson. Alluding to the use of opium, the poem describes a group of mariners who, upon eating the lotos, are put into an altered state and isolated from the outside world.

Autographed menu from the Lotos Club dinner in honor of Mark Twain, New York, 11 January 1908

In The Incredible Scofield and His Book, Joseph M. Canfield suspects that Scofield was associated with one of the Lotos Club’s committee members, Wall Street banker Samuel Untermyer (1858 – 1940).[118] An active Zionist, Untermyer was President of the Keren Hayesod, the agency through which the movement was conducted in America.[119] Untermyer was also reportedly a member of the Golden Dawn of New York and a British newspaper called him a “satanist.”[120] According to Prof. David W. Lutz, in Unjust War Theory: Christian Zionism and the Road to Jerusalem:

Untermeyer used Scofield, a Kansas city lawyer with no formal training in theology, to inject Zionist ideas into American Protestantism. Untermeyer and other wealthy and influential Zionists whom he introduced to Scofield promoted and funded the latter’s career, including travel in Europe.[121]

Samuel Untermyer blackmailed the American President Woodrow Wilson, with the knowledge of Woodrow Wilson’s affair with Mary Peck, the wife of a professor colleague, in return for appointing Louis Brandeis to the Supreme Court.[122] Finally, relying on the legal opinion of Justice Brandeis, Wilson declared war against Germany on April 7, 1917.

[1] Michael Howard. Secret Societies: Their Influence and Power from Antiquity to the Present Day (Inner Traditions/Bear & Company, Kindle Edition), p. 135.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Arthur Kamczycki. “Herzl’s Image and the Messianic Idea,” Studia Judaica 18 (2015), 2 (36), p. 17.

[4] Ibid., p. 248.

[5] See Yosef Salmon. “Tradition and Nationalism,” in Jehuda Reinharz, Anita Shapira (eds.), Essential Papers on Zionism (New York–London, 1995), p. 106; cited in Kamczycki. “Herzl’s Image and the Messianic Idea,” p. 248.

[6] Theodor Herzl. Altneueland: Roman (Leipzig, 1902), p. 27; cited in Kamczycki. “Herzl’s Image and the Messianic Idea,” p. 248.

[7] Klaus Polkehn. “Zionism and Kaiser Wilhelm.” Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Winter, 1975), pp. 76-90.

[8] Kaufmann Walter. Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist (Princeton University Press, 2008).

[9] William Mackintire Salter. “Nietzsche and the War.” International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 27, No. 3 (April, 1917), p. 357.

[10] Steven E. Aschheim. The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany, 1890–1990 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1992), p. 135

[11] A.D. Schrift. Nietzsche’s French Legacy: A Genealogy of Poststructuralism (Routledge, 1995).

[12] Jacob Golomb, ed. Nietzsche and Jewish culture (Routledge, 1997), pp. 234–35.

[13] Cited in Julius H. Schoeps. Pioneers of Zionism: Hess, Pinsker, Rülf (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2013), p. 76.

[14] Kornberg. Theodor Herzl, p. 52.

[15] Naomi Pasachoff. Great Jewish Thinkers: Their Lives and Work (Behrman House, 1992). p. 97.

[16] Israel Cohen. Theodor Herzl, founder of political Zionism (New York: T. Yoseloff, 1959), p. 210.

[17] Entry of January 23, 1904. In Marvin Lowenthal (ed. and trans.), The Diaries of Theodor Herzl (London, 1958), pp, 425–426; cited in Robert S. Wistrichin. “Theodor Herzl: Between Myth and Messianism,” in Mark H. Gelber & Vivian Liska (eds.), Theodor Herzl: From Europe to Zion (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag 2007), p. 19.

[18] Kamczycki. “Herzl’s Image and the Messianic Idea,” p. 244.

[19] “Chaim Bloch: Theodor Herzl and Joseph S. Bloch,” in Herzl Year Book 1 (1958), p. 158; cited in Wistrichin. “Theodor Herzl: Between Myth and Messianism,” p. 18.

[20] Robert S. Wistrichin. “Theodor Herzl: Between Myth and Messianism,” in Mark H. Gelber & Vivian Liska (eds.), Theodor Herzl: From Europe to Zion (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag 2007), p. 17.

[21] The Diaries of Theodor Herzl, ed. and trans. Maurice Lowenthal (Gloucester, 1978), 3: 960; cited in Kamczycki. “Herzl’s Image and the Messianic Idea,” p. 243.

[22] Theodor Herzl. Old-New Land (Haifa: Haifa Publishing Company 1960), p. 82-83; cited in Wistrichin. “Theodor Herzl: Between Myth and Messianism,” p. 17.

[23] John Rose. “Zionism under the microscope.” International Socialism (October 6, 2008).

[24] Gershom Scholem (1949). “The Curious History of the Six-Pointed Star. How the ‘Magen David’ Became the Jewish Symbol.” Commentary. Vol. 8. pp. 244.

[25] Ibid.. pp. 243–251.

[26] Ibid.. pp. 247.

[27] Ibid.. pp. 247.

[28] Jerry Klinger. “Richard Gottheil the Reluctant Father of American Zionism.” Jewish Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.jewishmag.com/118mag/richard_gottheil/richard_gottheil.htm

[29] Rabbi Antelman. To Eliminate the Opiate, Vol 2, p. 217.

[30] Richard Gottheil. “The Reluctant Father of American Zionism.”

[31] Gershom Scholem. “A Sabbatean Will Work from New York,” The Messianic Idea in Judaism: And Other Essays on Jewish Spirituality (New York: Schocken, 1971).

[32] Elinor Slater & Robert Slater. Great Jewish Men (Jonathan David Company, Inc, 1996), pp. 112–115.

[33] Jerry Rabow. 50 Jewish Messiahs: The Untold Life Stories of 50 Jewish Messiahs Since Jesus and how They Changed the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Worlds (Gefen Publishing House Ltd, 2002), p. 132.

[34] Barry Chamish. Shabtai Tavi, Labor Zionism and the Holocaust (Lulu), p. 292.

[35] “Religion: Jews v. Jews.” Time Magazine (June 20, 1938).

[36] Ibid.

[37] Donald M. Lewis, Richard V. Pierard. Global Evangelicalism: Theology, History & Culture in Regional Perspective (InterVarsity Press, 2014); Evan Burns. “Moravian Missionary Piety and the Influence of Count Zinzendorf.” Journal of Global Christianity (1.2 / 2015); Jonathan M. Yeager. Early Evangelicalism: A Reader (Oxford University Press, 2013); Mark A. Noll. The Rise of Evangelicalism: The Age of Edwards, Whitefield, and the Wesleys (InterVarsity Press, 2004).

[38] Tim O’Neill. “The Erotic Freemasonry of Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf,” in Secret and Suppressed: Banned Ideas and Hidden History, ed. Jim Keith (Feral House, l993), pp. 103-08.

[39] Catalin Negru. History of the Apocalypse (Lulu Press, 2015).

[40] Donald Lewis. The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftesbury And Evangelical Support For A Jewish Homeland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 380.

[41] “CMJ UK - The Church’s Ministry among Jewish People.” www.cmj.org.uk.

[42] Kelvin Crombie. A Jewish Bishop in Jerusalem: the life story of Michael Solomon Alexander (Jerusalem: Nicholayson’s, 2006).

[43] Hugh Chisholm, ed. “Friedrich Wilhelm II. of Prussia.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 (11th ed.). (Cambridge University Press, 1911), pp. 64–65.

[44] Boris Nicolaievsky & Otto Maenchen-Helfen. Karl Marx: Man and Fighter. trans. Gwenda David and Eric Mosbacher (Harmondsworth and New York: Pelican, 1976), pp. 4–6.

[45] R. Larry Todd. Mendelssohn – A Life in Music (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. 2003), p. 33.

[46] Clive Brown. A Portrait of Mendelssohn (New Haven and London: Yale University Press. 2003), p. 84.

[47] Laura K.T. Stokes. “Mendelssohn’s Deutsche Liturgie in the Context of the Prussian Agenda of 1829.” In Rethinking Mendelssohn, ed. Benedict Taylor Ph.D. (Oxford University Press, 2020), p. 347.

[48] Hillel Halkin. “Power, Faith, and Fantasy by Michael B. Oren.” Commentary (January 1, 2007).

[49] “Palestine Exploration Fund.” Quarterly Statement for 1875 (London, 1875). p. 116.

[50] Geoffrey H. White, ed. The Complete Peerage, Volume XI. (St Catherine’s Press, 1949), p. 4.

[51] Ben-Dov. In the Shadow of the Temple, p. 347

[52] Rupert L. Chapman III. Tourists, Travellers and Hotels in 19th-Century Jerusalem: On Mark Twain and Charles Warren at the Mediterranean Hotel (Routledge, 2018).

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ellic Howe. “Fringe Masonry in England, 1870-85.” Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, the Transactions of Quatuor Coronati Lodge No. 2076, UGLE in Volume 85 (September 14, 1972).

[55] Letters of George Gissing to members of his family, collected and arranged by Algernon and Ellen Gissing. (London: Constable, 1927), letter dated 6/3/1884.

[56] Howard. Secret Societies; Goodrick-Clarke. The Occult Roots of Nazism, p. 113.

[57] Dorothe Sommer. Freemasonry in the Ottoman Empire (I. B. Tauris, Londra-New-York, 2015), p. 80.

[58] Dr. Winslow, the examining pathologist, quoted in Robert F. Haggard. “Jack the Ripper As the Threat of Outcast London.” Essays in History. Volume 35. (Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, 1993).