18. The Frankfurt School

Defeating Evil from Within

Leading American Fabians contributed to several organizations as instruments to advance left-wing ideals. One of the more important of these is the New School for Social Research, founded in 1919.[1] The New York State Legislative Committee described the New School as: “established by men who belong to the ranks of near-Bolshevik Intelligentsia, some of them being too radical in their views to remain on the faculty of Columbia University.”[2] British Fabians such as Sir William Beveridge, J.M. Keynes, Graham Wallas, Julian Huxley, Bertrand Russell, J.B.S. Haldane and Harold Laski lectured at the New School for Social Research. The American counterparts of the British Fabians included such personages as: John Dewey, Clarence Darrow, Roger Baldwin, Felix Frankfurter, Franz Boas, Wesley C. Mitchell, Harry A. Overstreet, Max Ascoli and Walter Lippmann. Soviet partisans such as: Moissaye Olgin (later exposed as a top Soviet agent) also participated in the New School activities.[3]

New School for Social Research

The New School for Social Research would become closely associated with the Frankfurt School, founded in 1923 by a predominantly Jewish group of philosophers and Marxist theorists as the Institut für Sozialforschung, “Institute for Social Research,” at the University of Frankfurt. Despite their association with Marxism, there was a curious overlap between the Jewish members of the Frankfurt School, the exponents of the German Conservative Revolution, including the George-Kreis and the Munich Cosmic Circle, and the burgeoning field of History of Religions associated with the Eranos conferences. Together, they shared the influence of Sabbatean antinomianism, in a transgressive approach to art and culture, referred by Steven M. Wasserstrom to as “defeating evil from within.”[4]

The Frankfurt School’s main figures sought to learn from and synthesize the works of such varied thinkers as Kant, Hegel, Freud, Max Weber and Georg Lukacs, focusing on the study and criticism of culture developed from the thought of Freud. The Frankfurt School’s most well-known proponents included Max Horkheimer (1895 – 1973), Erich Fromm (1900 – 1980), media theorist Theodor Adorno (1903 – 1969), Herbert Marcuse (1898 – 1979), Walter Benjamin (1892 – 1940) and Jurgen Habermas (b. 1929). Martin Jay, in his history of the Frankfurt School, concedes that the Kabbalah would have had some influence as well, as noted by Habermas. Jay summarizes:

Jurgen Habermas has recently argued that a striking resemblance exists between certain strains in the Jewish cultural tradition and in that of German Idealism, whose roots have often been seen in Protestant Pietism. One important similarity, which is especially crucial for an understanding of Critical Theory, is the old cabalistic idea that speech rather than pictures was the only way to approach God.[5]

Several of the key members of the group had orthodox Jewish upbringings, or at least studied and practiced some elements of Judaism. For Walter Benjamin and Erich Fromm, their Judaic heritage figured importantly in key stages of their lives and works. Judaism was only of some significance at different stages for Leo Löwenthal and Max Horkheimer, while the religion appears not to have been particularly important for Marcuse and Adorno. According to Wasserstrom, Adorno was another example of “cultural Sabbateanism,” when he stated: “Only that which inexorably denies tradition may once again retrieve it.”[6] Jurgen Habermas cites the example of the Minima Moralia of Adorno who, despite his apparent secularism, explains that all truth must be measured with reference to the Redemption—meaning the fulfillment of Zionist prophecy and the advent of the Messiah:

Philosophy, in the only way it is to be responsive in the face of despair, would be the attempt to treat all things as they would be displayed from the standpoint of redemption. Knowledge has no light but what shines on the world from the redemption; everything else is exhausted in reconstruction and remains a piece of technique. Perspectives would have to be produced in which the world is similarly displaced, estranged, reveals its tears and blemishes the way they once lay bare as needy and distorted in the messianic light.[7]

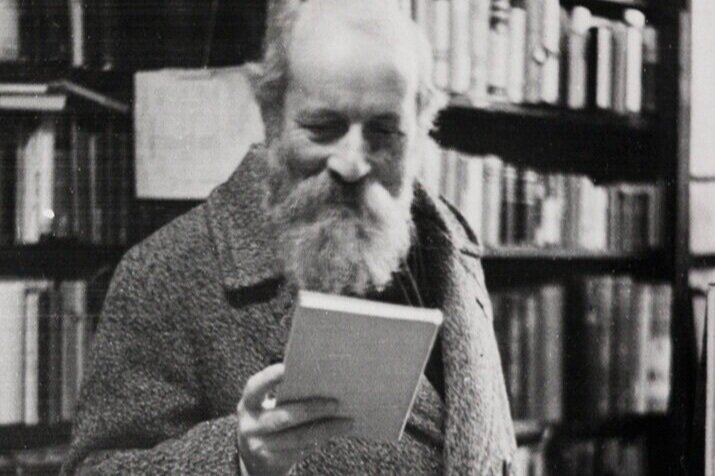

Gershom Scholem (1897 – 1982), founder of the modern, academic study of Kabbalah, and close friend of Theodore Adorno, Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin and Leo Strauss

Martin Buber

Steven M. Wasserstrom explains that the scholar responsible for communicating the Frankist notion of “defeating evil from within” was Gershom Scholem (1897 – 1982), a regular speaker at the Eranos conferences, and the renowned twentieth-century expert on the Kabbalah, who is regarded as having founded the academic study of the subject. As Wasserstrom noted, Scholem’s classic essay about Sabbatian antinomianism, “Redemption through Sin,” published in 1937, “remains one of the most influential essays written not only in Jewish Studies but in the history of religions more generally.”[8] According to Scholem:

Evil must be fought with evil. We are thus gradually led to a position which as the history religion shows, occurs with a kind of tragic necessity in every great crisis of the religious mind. I am referring to the fatal yet at the same time deeply fascinating doctrine of the holiness of sin.[9]

Scholem, along with Hans Kohn and Hugo Bergmann, was among the leaders of Brit Shalom, a small Zionist faction that advocated binationalism. Zohar Maor has argued that that their purported moderation and consistent opposition to the prevailing Zionist agenda of a Jewish state in Palestine issued from völkisch nationalism. [10] Scholem saw Buber as the herald of the Messiah, and as the only Zionist thinker who truly grasped Judaism’s depth.[11] In The Founding Myths of Israel, Ze’ev Sternhell explains that Scholem not only did not abandon Buber’s völkism, but even adopted its most hazardous aspect: its immoralism.[12] In an unpublished draft essay, “Politik des Zionismus,” Scholem argued: “Morality is a little nonsense [Geschwätz] (when it is rightly understood; when wrongly understood it is most essential).” As explained by Sternhell, Scholem defined politics as a realm in which actions are principally regarded as means. In effect, politics is a closed system where external considerations are irrelevant. Scholem argued, “The demand for equivalence of the political and the ethical, not to speak of the popular demand for their identification… is a conceptual confusion.”[13] For that reason, Scholem wrote, “Sometimes I start to think that Friedrich Nietzsche is the only one in modern times who said anything substantial about ethics.”[14]

Of great importance for Scholem was Franz Joseph Molitor, a member of Asiatic Brethren, and according to whom the order drew on the magic of the Sabbateans, “such as Sabbatai Zevi, Falk (the Baal Shem of London), Frank, and their similar fellows.”[15] According to Joseph Dan, holder of the Gershom Scholem Chair of Kabbalah at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Scholem was first and foremost a Jewish nationalist and not a mystic. However, there have been differing views on this point. Scholem was deliberately cryptic about his interest in the occult, feigning scientific disinterest: “I am certainly no mystic, because I believe that science demands a distanced attitude.”[16] As explained by Joseph Weiss, one of Scholem’s closest pupils, “His esotericism is not in the nature of an absolute reticence, it is a kind of camouflage.”[17]

In his youth, Scholem carried out practical exercises based on Abraham Abulafia’s mystical techniques. In 1928, he published an essay entitled “Alchemie und Kabbala” in the journal Alchemistische Blätter, published by Otto Wilhelm Barth, probably the most important occult publisher and bookseller in Germany at the time, along with the Pansophist Heinrich Tränker, with whom Barth collaborated. As discovered by Konstantin Burmistrov, not only did Scholem possess many classics of occultism, including the works of Eliphas Lévi, Papus, Francis Barrett, McGregor Mathers, A.E. Waite, Israel Regardie, and so on, but his handwritten marginal notes show that he studied these works intensively. According to Burmistrov, the essay on “Alchemie und Kabbala” reveals the strong influence of A.E. Waite.[18] Scholem was also apparently interested in chiromancy, a subject he discussed with three women he called, all of whom were associated with Eranos: the graphologist and student of Jung, Anna Teillard-Mendelsohn; Hilde Unseld, first wife of Siegfried Unseld, the influential publisher of Suhrkamp; and Ursula von Mangold, a niece of Walther Rathenau and later director O.W. Barth publishing house, which in 1928 had planned the publication of a journal with the title Kabbalistische Blätter. Scholem’s went to visit the occult novelist and Golden Dawn member Gustav Meyrink, and expressed a positive opinion about the parapsychological investigations of Emil Matthiesen (1875 – 1939).[19]

Scholem, by tracing the origins of Jewish mysticism from its beginnings in Merkabah all the way forward to its final culmination in the messianic movement of Sabbatai Zevi, rehabilitated perceptions of the Kabbalah as not a negative example of irrationality or heresy but as supposedly vital to the development of Judaism as a religious and national tradition.[20] According to Scholem’s “dialectical” theory of history, Judaism passed through three stages. The first is a primitive or “naïve” stage that lasted to the destruction of the Second Temple. The second is Talmudic, while the final is a mystical stage which recaptures the lost essence of the first naïve stage, but reinvigorated through a highly abstract and even esoteric set of categories. In order to neutralize Sabbateanism, Hasidism had emerged as a Hegelian synthesis.

According to Wasserstrom, Scholem’s classic essay “Redemption Through Sin,” “remains one of the most influential essays written not only in Jewish Studies but in the history of religion more generally.”[21] The appearance of the mystical messiah, explained Scholem, caused an “inner sense of freedom” which was experienced by thousands of Jews. He explains, “powerful constructive impulses… [at work] beneath the surface of lawlessness, antinomianism and catastrophic negation… Jewish historians until now have not had the inner freedom to attempt the task.”[22] In Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, Scholem speaks of the “deeply fascinating doctrine of the holiness of sin,” and in On The Kabbalah and its Symbolism he confesses that “[o]ne cannot but help be fascinated by the unbelievable freedom… from which their own world seemed to construct itself.”[23] Scholem told his friend Walter Benjamin of his attraction to “the positive and noble force of destruction,” and declared that “destruction is a form of redemption.”[24]

The influence of Hasidism in the Frankfurt School was also felt in the thought of Erich Fromm, who was also deeply immersed in Judaism and later indicated how he was influenced by the messianic themes in Jewish thought. Central to Fromm’s worldview was his interpretation of the Talmud and Hasidism. He began studying Talmud as a young man under Rabbi J. Horowitz and later under Rabbi Salman Baruch Rabinkow, a Chabad Hasid. While working towards his doctorate in sociology at the University of Heidelberg, Fromm studied the Tanya by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder of Chabad.[25]

Critical Theory

Clockwise from top left: Erich Fromm (1900 – 1980), Theodor Adorno (1903 – 1969), Max Horkheimer (1895 – 1973), Walter Benjamin (1892 – 1940), Herbert Marcuse (1898 – 1979), Franz Neumann (1900 – 1954), Friedrich Pollock (1894 – 1970) and Leo Löwenthal (1900 – 1993)

The term Frankfurt School describes the works of scholarship and the intellectuals who were the Institute for Social Research (Institut für Sozialforschung), an adjunct organization at Goethe University Frankfurt, founded in 1923, by Carl Grünberg, a Marxist professor of law at the University of Vienna. The Frankfurt School originated through the financial support of the wealthy student Felix Weil (1898 – 1975), a Jewish German-Argentine Marxist. In 1922, Weil organized the First Marxist Workweek (Erste Marxistische Arbeitswoche) in effort to synthesize different trends of Marxism into a coherent, practical philosophy. The success of the Workweek prompted the formal establishment of a permanent institute for social research.

Georg Lukács participated in the Arbeitswoche. During the Hungarian Soviet Republic, Lukács was a theoretician of the Hungarian version of Red Terror, a period of political repression and mass killings carried out by Bolsheviks after the beginning of the Russian Civil War in 1918. In an article in the Népszava, in 1919, he wrote that “The possession of the power of the state is also a moment for the destruction of the oppressing classes. A moment, we have to use.”[26] Lukács later became a commissar of the Fifth Division of the Hungarian Red Army, and ordered the execution of eight of his own soldiers in 1919. In that same year, he fled to Vienna was arrested, but was saved from extradition due to a group of writers including Thomas and Heinrich Mann. Thomas Mann later based the character Naphta on Lukács in his novel The Magic Mountain. During his time in Vienna in the 1920s, Lukács befriended other Left Communists who were working or in exile there, including Victor Serge, Adolf Joffe and Antonio Gramsci. In 1924, shortly after Lenin’s death, Lukács published in Vienna the short study Lenin: A Study in the Unity of His Thought. In 1925, he published a critical review of Nikolai Bukharin’s manual of historical materialism.

In addition to Hegel, Marx, and Weber, Freud became one of the foundation stones on which the Frankfurt School’s interdisciplinary program for a critical theory of society was constructed. The philosophical tradition of the Frankfurt School is associated with the philosopher Max Horkheimer, who became the director in 1930, and recruited intellectuals such as Theodor W. Adorno, Erich Fromm, and Herbert Marcuse.[27] In 1927, Fromm, a trained psychoanalyst, helped to found the Frankfurt Psychoanalytic Institute which shared a building with the Frankfurt School. Eminent psychoanalysts like Anna Freud, Paul Federn, Hans Sachs, and Siegfried Bernfeld gave lectures to the general public, sponsored by the Frankfurt School. Horkheimer also sat on the board of the Psychoanalytic Institute. Fromm, a member of both institutes, helped the Critical Theorists educate themselves about the fundamentals of psychoanalytic theory.[28]

The Frankfurt School’s “critical theory” was defined by Horkheimer in Traditional and Critical Theory (1937) as social critique meant to effect sociologic change and realize intellectual emancipation, by way of enlightenment that is not dogmatic in its assumptions.[29] The purpose of critical theory is to analyze the true significance of the ruling understandings (the dominant ideology) generated in bourgeois society, by showing that the dominant ideology misrepresents how human relations occur in the real world, to legitimate the domination of people by capitalism. Hence, the task of the Frankfurt School was sociological analysis and deconstruction of the ruling-class narrative as an alternative path to realizing the Marxist revolution.

Members of the Frankfurt School were initially positive towards Heidegger, but became more critical at the beginning of the 1930s following his drift to the right. In 1928, Marcuse studied with Husserl and wrote a Habilitation with Heidegger, which was published in 1932 as Hegel’s Ontology and Theory of Historicity. Walter Benjamin, an ardent Zionist who was highly influenced by his close friend Gershom Scholem, had also studied under Husserl and Heidegger. While Benjamin is conventionally associated with the political left, Benjamin the defining moment of his intellectual trajectory was a “dangerous encounter” from the year 1922 when he met George-Kreis’ member Ludwig Klages, whom Georg Lukacs recognized a “pre-Fascist irrationalist.”[30] As Jürgen Habermas noted in his seminal essay “Consciousness-Raising or Redemptive Critique: The Actuality of Walter Benjamin”: “Benjamin, who uncovered the prehistoric world by way of Bachofen, knew [Alfred] Schuler, appreciated Klages, and corresponded with Carl Schmitt—this Benjamin, as a Jewish intellectual in 1920s Berlin, could still not ignore where his (and our) enemies stood.”[31] In a 1925 letter a wrote he wrote to Scholem, Benjamin declared that “a confrontation with Bachofen and Klages is unavoidable.”[32] Letters found in the Klages archive revealed that plans were in place to create a Nazi leadership school based on Klages’ Lebensphilosophie. Benjamin himself pointed out, in “Theories of German Fascism,” a review of Jünger’s collection War and Warriors (1930), about those “habitués of the chthonic forces of terror, who carry their volumes of Klages in their packs.”[33]

Leo Strauss (1899 – 1973)

Benjamin and Carl Schmitt were both obsessed by the “state of exception.”[34] According to Wasserstrom, Schmitt was another example of “cultural Sabbatianism,” expressed through the “imperative to defeat evil from within.” [35] Despite his Nazi affiliations, Schmitt was also associated closely with well-known Jewish philosophers like Walter Benjamin and Leo Strauss (1899 – 1973).[36] As a youth, Strauss was “converted” to political Zionism as a follower of Zeev Jabotinsky. He was also friends with Gershom Scholem and Walter Benjamin, who were both strong admirers of Strauss. He would also attend courses at the University of Freiburg taught by Martin Heidegger. Because of the Nazis’ rise to power, he chose not to return to his native country and ended up in the United States, where he spent most of his career as a professor of political science at the Rockefeller-funded University of Chicago.

Strauss’s critique and clarifications of The Concept of the Political (1932) led Schmitt to make significant emendations in its second edition. Schmitt’s work has attracted the attention of numerous philosophers and political theorists, including Frankfurt Schoolers Walter Benjamin and Jürgen Habermas, as well as Friedrich Hayek, Jacques Derrida, Hannah Arendt and Giorgio Agamben. Schmitt’s highly positive reference for Leo Strauss was instrumental in winning Strauss the scholarship funding that allowed him to leave Germany, when he ended up teaching at the University of Chicago, at the invitation of its then-President, Robert Maynard Hutchins (1899 – 1973).[37] Strauss became an American citizen in 1944, and in 1949 he became a professor of political science at the University of Chicago, holding the Robert Maynard Hutchins Distinguished Service Professorship until he left in 1969.

Prior to teaching at the University of Chicago, Strauss had secured a position at The New School of Columbia University where he joined the Frankfurt School exiles. Following Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, members of the Frankfurt School left Germany for Geneva before moving to New York in 1935, where they became affiliated with the New School. There, they became associated with the University in Exile, which the New School had founded in 1933, with financial contributions from the Rockefeller Foundation, to be a haven for scholars dismissed from teaching positions by the Italian fascists or Nazi Germany. Notable scholars associated with the University in Exile include Erich Fromm, Hannah Arendt and Leo Strauss. As Frankfurt School historian Martin Jay explains, “And so the International Institute for Social Research, as revolutionary and Marxist as it had appeared in Frankfurt in the twenties, came to settle in the center of the capitalist world, New York City.”[38]

Transgression

George Bataille (1897 – 1962)

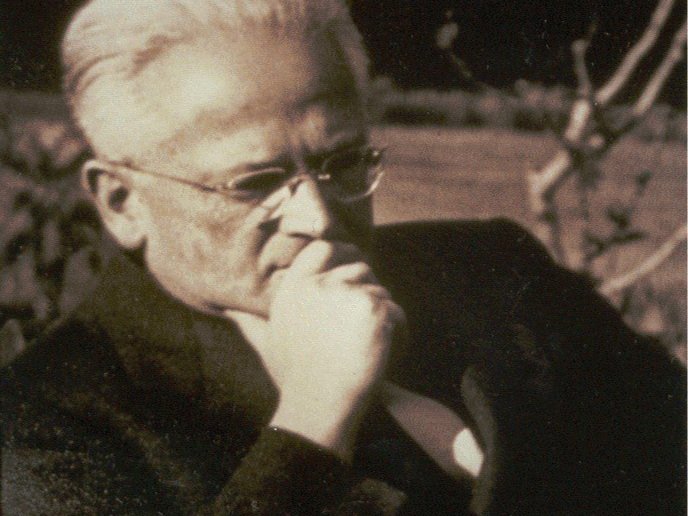

Martin Heidegger’s friend Karl Jaspers

Walter Benjamin corresponded much with Theodor Adorno and Bertolt Brecht, and was occasionally funded by the Frankfurt School under the direction of Adorno and Max Horkheimer. Benjamin befriended novelist Hermann Hesse, composer Kurt Weill, and Hannah Arendt—who had a romantic relationship with Heidegger, and studied under his friend Karl Jaspers. The surrealists also looked to the Marxist dialectic and the work of such Frankfurt School exponents as Benjamin and Marcuse. In 1937, Benjamin met George Bataille (1897 – 1962), who was linked through friendship with several participants of the Eranos conferences. Bataille was also affiliated with the Surrealists, and heavily influenced by Hegel, Freud, Marx, the Marquis de Sade and Friedrich Nietzsche and Guénon.[39] Benjamin later preserved Bataille’s Arcades Project manuscript, attended meetings of the College de Sociology and Bataille’s Acéphale society, and was reportedly accompanied by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer.[40]

The core of Bataille’s work is characteristic of writers who have been categorized within “literature of transgression.” Jeffrey Mehlman links the transgressive and antinomian elements in Bataille’s thought to Sabbateanism through Benjamin’s friendship with Scholem.[41] Bataille’s writing has been categorized as “literature of transgression.” He was a coprophiliac, a necrophiliac and committed, by his own confession, an incestuous sexual act, in a state of “arousal to the limit,” upon his mother’s corpse after her death.[42] Bataille wrote that human beings, as a species, should move towards “an ever more shameless awareness of the erotic bond that links them to death, to cadavers, and to horrible physical pain.”[43] His novel Histoire de l’oeil (“Story of the Eye”), published under the pseudonym Lord Auch (literally, Lord “to the shithouse,” was initially read as pure pornography, while Blue of Noon, which had autobiographical undertones, explored incest, necrophilia, and politics. Bataille, wrote one of his admirers, “displayed a quasi-religious veneration” of the disgusting. He added:

Herein lie the affinities between Bataille’s world view and the discourse of “negative theology” or redemption through sin… The duality between the ‘sacred’ and the ‘profane’ obsessed him, but the habitual signs were reversed. He elevated acts of profanation or desecration to epiphanies: singular mystical moments of Oneness with the All… For Bataille… the act of willfully violating taboos offered privileged access to the holy.[44]

Bataille , along with Man Ray and André Breton, was also among the several personalities of the avant-garde who participated in the sessions of Maria de Naglowska, a member of the Ur Group with Julius Evola.[45] According to Hugh Urban, Naglowska’s work shares much with Bataille’s writings on mysticism, death, and sexuality.[46] “The Sacred Conspiracy” alludes to three such activities, which include play, eroticism, and sacrifice. Fascinated by human sacrifice, Bataille founded a secret society, Acéphale, the symbol of which was a headless man. According to legend, Bataille and the other members of Acéphale each agreed to be the sacrificial victim as an inauguration, though none of them would agree to be the executioner.[47] In “The Sacred Conspiracy,” the call to arms which Bataille published in the first issue of Acephale, he exhorted his followers “to abandon the world of the civilized and its light,” and to turn to “ecstasy” and the “dance that forces one to dance with fanaticism.”[48]

Pierre Klossowski (1905 – 2001)

Members of Acéphale were also invited to meditation on texts of Nietzsche, Freud and Marquis de Sade, after whom the words “sadism” and “sadist” were derived, and whose is best known for the execrable The 120 Days of Sodom. Before World War I, Guillaume Apollinaire announced that de Sade was “the freest spirit who ever lived.” Starting in the 1930s, French philosophers Simone de Beauvoir, Maurice Blanchot, Jean Paulham, Pierre Klossowski, and George Bataille celebrated the sovereign transgressor, the Marquis de Sade, as a model of perfect freedom. According to Wasserstrom, at the same time French writer and artist Pierre Klossowski (1905 – 2001) was extolling de Sade as a liberator contributing to the spirit that led to the French Revolution, Scholem described Jacob Frank in much the same terms in “Redemption through Sin.”[49] Both recognized here the inheritance of ancient Gnosticism.[50] According to Klossowski:

The evil must, therefore, erupt once and for all; the bad seed has to flourish so the mind can tear it out and consume it. In a word, evil must be made to prevail once and for all in the world so that it will destroy itself and so Sade’s mind can find peace.[51]

Klossowski participated in most issues of Bataille’s Acéphale in the late 1930s. Pierre was the eldest son of Baladine Klossowska, who was descended from Russian Jews who had emigrated to East Prussia, and his younger brother was the painter Balthus. The Klossowski children grew up in an art-world environment, with frequent visits to their household by famous artists and writers, including Pierre Matisse, André Gide—who mentored Pierre. These also included Rainer Maria Rilke, considered one of the most significant poets in the German language—with whom his mother had an affair. Rilke was also a friend to Gurdjieff’s collaborator, Thomas de Hartmann. Rilke had an affair with Freud’s assistant, Lou Andreas-Salomé, whom Nietzsche had been in love with.

Klossowski knew Benjamin and translated his article for a Frankfurt School publication, edited by Horkheimer and Adorno. Benjamin met Klossowski in 1935, during a meeting of “Counter-Attack,” the political group founded by Bataille and Andre Breton. Bataille and Breton were not on good terms, but managed to reconcile briefly in order to recruit intellectuals in support of Leon Blum’s Popular Front. At the beginning of 1936, the Frankfurt School engaged Klossowski to translate Benjamin’s essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” for their journal, the Zeitschrift für Sozialforshung. The Frankfurt School also engaged Klossowski to translate a number of Horkheimer’s works. Benjamin favorably reviewed Klossowski’s article, “Evil and the Negation of the Other in the Philosophy of D.A.F. de Sade,” in the Zeitschrift. Klossowski also credits Benjamin with introducing him to the study of Gnosticism through a German volume Benjamin lent him on Valentinus, Basilides, and other heretics.[52]

Together with other contributors to Acéphale, Bataille published a special issue in 1937 titled Réparation á Nietzsche (“Repair of Nietzsche). Before 1939, there was a broad consensus that Nietzsche was the ideological godfather of fascism and Nazism.[53] Contributors included critics of Nazism like Heidegger’s friend Karl Jaspers and Karl Löwith, who sought to rehabilitate Nietzsche by suggesting that he had been misappropriated. A student of Husserl and Heidegger, Löwith was one of the most prolific German philosophers of the twentieth century. From 1941 to 1952, he taught at the Hartford Theological Seminary and The New School for Social Research. In an essay “On My Philosophy,” Jaspers wrote: “While I was still at school Spinoza was the first. Kant then became the philosopher for me and has remained so… Nietzsche gained importance for me only late as the magnificent revelation of nihilism and the task of overcoming it.” In “Nietzsche’s Madness,” Bataille says, “He who has once understood that in madness alone lies man’s completion, is thus led to make a clear choice not between madness and reason, but between the lie of ‘a nightmare of justifiable snores,’ and the will to self-mastery and victory.”[54]

College of Sociology

Denis de Rougemont (1906 – 1985)

Mircae Eliade, member of the Ur Group

As summarized by Wasserstrom, “In short, Scholem’s antinomian necessity ‘to defeat evil from within’ enjoyed a certain elective affinity not only with the College of Sociology, Eranos, and the history of religions, but with a scattered elite of postreligious intellection.”[55] Founded by Bataille and Klossowski, the College of Sociology was a loosely-knit group of French intellectuals, named after the informal discussion series that they held in Paris between 1937 and 1939, when it was disrupted by the war. The group met for two years and lectured on many topics, including the structure of the army, the Marquis de Sade, English monarchy, literature, sexuality, Hitler, and Hegel. Participants also included Hans Mayer, Jean Paulhan, Jean Wahl, Michel Leiris, Alexandre Kojève and André Masson. The College published Klossowski’s “The Marquis de Sade and the Revolution” in 1939.

Swiss writer and cultural theorist Denis de Rougemont, who wrote the classic work Love in the Western World, was another leader of the College of Sociology. De Rougemont introduced Paris to the works of Heidegger, Kierkegaard, and Karl Barth before World War II, through his magazine Hic et Nunc. He wrote the classic work, Love in the Western World, which explores Sufi influence on the psychology of love from Courtly Love and from the legend of Tristan and Isolde to Hollywood. At the heart of his inquiry is what he regards as the inescapable conflict in the West between marriage and passion. Marriage is a formal convention associated with social and religious responsibility, while passion has its roots in the accounts of unrequited love celebrated by the troubadours of medieval Provence, acknowledging their debt to the Sufis. These early poets, according to de Rougemont, preached an Eros-centered theology, by which this mystical erotic tradition was inherited in the West.

The College of Sociology reflected an interest in sacred sociology, referred to as the sacred of the Left Hand. One motif was the study of the transgressive quality of the festival, recalling the moral reversals of the ancient Saturnalia and Feast of Fools. Roger Caillois, cofounder of the College, author of Man and the Sacred who several times published Scholem, wrote in the influential “theory of celebrations” that, “This interval of universal confusion represented by the festival masquerades as the moment in which the whole world is abrogated. Therefore all excesses are allow during it. Your behaviour must be contrary to the rule. Everything should be back to front… in this way all those laws which protect the good natural and social order are systematically violated.”[56] Similarly, de Rougemont wrote in The Devil’s Share: “[T]he overturning of the moral laws (thou shalt kill, thou shalt steal, thou shalt bear false witness, with honour); the suspension of law; limitless expenditures; human sacrifice; disguises; processions; unleashing of collective passions; temporary disqualifications of individual conflicts. I speak of a state of exception as one might say a state of side or a state of grace.”[57]

Klossowski was to enjoy a strong relationship with the work of Henry Corbin and Mircae Eliade—Traditionalist historian, Ur Group member and friend of Bataille—key figures and longtime associates of Scholem’s at the Eranos conferences. Denis de Rougemont once evoked the Eranos ideal with the slogan, “Heretics of the World Unite!”[58] Over the years, interests at Eranos included, Yoga and Meditation in East and West, Ancient Sun Cults and the Symbolism of Light in the Gnosis and in Early Christianity, Man and Peace, Creation and Organization and The Truth of Dreams.

Participants over the years have included the scholar of Hinduism, Heinrich Zimmer, Karl Kerényi the scholar of Greek mythology, Mircea Eliade, Gilles Quispel the scholar of Gnosticism, Gershom Scholem, and Henry Corbin a scholar of Islamic mysticism.[59] Following John Woodroffe, also known as Arthur Avalon, a number of scholars began investigating Tantric teachings, including scholars of comparative religion and Indology such as Agehananda Bharati, Mircea Eliade, Julius Evola, Carl Jung, Alexandra David-Néel, Giuseppe Tucci and Heinrich Zimmer. According to Hugh Urban, Zimmer, Evola and Eliade viewed Tantra as “the culmination of all Indian thought: the most radical form of spirituality and the archaic heart of aboriginal India,” regarding it as the ideal religion for the modern era. All three saw Tantra as “the most transgressive and violent path to the sacred.”[60]

Towards the end of the 1930s Kerényi also came into personal contact with Julius Evola.[61] In 1937, Corbin obtained his first academic post at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes in Paris. His friendships included, in addition to Georges Bataille and Roger Caillois, the specialist on Indo-European mythology Georges Dumézil and the philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev.[62]

De Rougemont’s The Devil’s Share was funded, like Scholem’s Sabbatai Zevi the Mystical Messiah, by Mary Mellon, patron of the Eranos group and the Bollingen Foundation.[63] Despite his anti-Semitism, Gershom Scholem, as reported by Mircea Eliade, stated that Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, the founder of the German Faith Movement who spoke at Eranos in 1934, was among the very few Nazis against whom he had no objection.[64] Scholem was among those authors subsidized by the Bollingen Foundation, and it was Paul Radin, another Eranos lecturer, who convinced its director John Barrett of the importance of his work on Sabbatai Zevi.[65] According to Gershom Scholem

When we, Adolf Portmann, Erich Neumann, Henry Corbin, Ernst Benz, Mircea Eliade, Karl Kerényi and many others—scholars of religion, psychologists, philosophers, physicists and biologists—were trying to play our part in Eranos, the figure of Olga Fröbe was crucial—she whom we always referred to among ourselves as “the Great Mother.” Olga Fröbe was an unforgettable figure for anyone who came here regularly or for any length of time. I have never been a great Jungian… but I have to say that Olga Fröbe was the living image of what in Jungian psychology is called the Anima and the Animus.[66]

Although the Bollingen Series was not a Traditionalist organization, it published the works of central figures in Traditionalism, like René Guénon’s leading disciple Ananda Coomaraswamy and Eliade. Coomaraswamy was in correspondence with Eliade from at least 1936, and also knew Heinrich Zimmer, the German Indologist who was close to Mary Mellon. The Mellons also befriended the Islamicist Louis Massignon, who was a professor at both the Collège de France and the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (EPHE). Massignon’s circle of acquaintances encompassed virtually the whole intellectual elite of France at the time and included Klossowski, Jacques Maritain, Jean Cocteau, and the Eranos speaker Cardinal Jean Daniélou. Massignon first spoke at Eranos in 1937 and for eighteen years he was one of its most regular speakers. After he met the Mellons, plans were made to publish several of his works in the United States, notably his study of the al-Hallāj, a Sufi mystic who was executed for pronouncing “I am the Truth.” Jung owed much of his knowledge of Islam to his friendship with Massignon. One figure who especially aroused Jung’s interest was the mysterious saint of Sufi tradition al Khidr (“the Green One”), worshipped simultaneously by Jews and Christians as Elijah and Saint George. Massignon was also close with Martin Buber, whom he described as “the last one to keep alive the sense of the sacred in Israel.”[67]

Last Taboo

Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908 – 2009)

Les Enfants Terribles (“The Terrible Children”) a 1950 film with a screenplay by Jean Cocteau, based on his 1929 novel.

Through Freud’s influence, the “incest taboo” would become an issue of fundamental concern to the Frankfurt School. Freud’s theories were excessively concerned with sex and even incest, which is reflected in Sabbateanism. As Scholem noted, the Sabbateans were particularly obsessed with upturning prohibitions against sexuality, particularly those against incest. Orgiastic rituals were preserved for a long time among Sabbatean groups and among the Dönmeh until about 1900.[68] Thus, Freud disguised a Frankist creed with psychological jargon, proposing that conventional morality is an unnatural repression of the sexual urges imposed during childhood. Freud theorized about incest and used the Greek myth of Oedipus to point out how much he believed that people desire incest and must repress that desire.

With the support of the Rockefeller Foundation, the New School also played a role in the founding of the École Libre des Hautes Études in 1942 in New York, by French academics in exile from the École pratique des hautes études (EPHE), as an instrument of intellectual resistance, in order to welcome intellectuals fleeing Europe.[69] Its founders included Jacques Maritain, and Jewish philosophers Jean Wahl (1888 – 1974) and Gustave Cohen (1879 – 1958). Maritain’s friend, Jean Cocteau, who was another visitor to Pierre Klossowski’s household, depicted the family in scenes of his 1929 Les Enfants Terribles, a novel about an incestuous relationship between a brother and a sister. In addition to Les Enfants Terribles, Cocteau is best known for the films The Blood of a Poet (1930), Beauty and the Beast (1946), Les Parents terribles (1948), and Orpheus (1949). Cocteau designed the set for a production of the occult-inspired opera Pelléas et Mélisande. Cocteau wrote the mildly homoerotic and semi-autobiographical Le livre blanc (“The White Book”), and his work was pervaded with homosexual undertones, homoerotic imagery, symbolism or camp.

Jean Wahl, another member of the College of Sociology, began his career as a follower of Henri Bergson and William James and is known as among those who introduced Hegelian thought in France in the 1930s. In the second issue of Acéphale, Georges Bataille’s review, Wahl wrote an article titled “Nietzsche and the Death of God,” concerning Karl Jaspers’ interpretation of his work. The reception of Jaspers, Heidegger’s secretary, in the English-speaking world was strongly affected by the critique of his work initiated by Georg Lukacs, Ernst Bloch, and subsequently by associates of the Frankfurt School, all of whom accused him of some degree of intellectual complicity in the rise of the German fascism in the early 1930s.[70] Wahl came to the U.S. after having escaped from being interned as a Jew at the Drancy internment camp, north-east of Paris.

Historian Elias Bickerman and linguist Roman Jakobson (1896 – 1982) all taught at the École Libre. Jakobson, a pioneer of structural linguistics, was associated with the Frankfurt School. Jakobson was born in Russia in 1896 to a well-to-do family of Jewish descent. Jakobson escaped from Prague in early March 1939, and ended up in New York, where he taught at the New School, the American branch of the Frankfurt School, where he was closely associated with the Czech émigré community. With his close friend, the Russian Eurasianist Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Jakobson in effect founded the modern discipline of phonology. Through his decisive influence on Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908 – 2009) and Roland Barthes (1915 – 1980), among others, Jakobson became a pivotal figure in the adaptation of structural analysis to disciplines beyond linguistics, including philosophy, anthropology, and literary theory.[71]

Mauss (1872 – 1950)

In 1941, Jewish-French anthropologist and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who considered the universal taboo against incest as the cornerstone of human society, was granted admission to the United States and offered a position at the New School in New York. Alongside James Frazer and Franz Boas, Lévi-Strauss is regarded as the “father of modern anthropology.” Incest, Lévi-Strauss believed, was not naturally repugnant, but became prohibited through culture. Lévi-Strauss’ theory was based on an analysis of the work of Marcel Mauss (1872 – 1950) who believed that the basis of society is the need for the exchange of gifts. Because fathers and brothers would be unwilling to share their wives and daughters, a shortage of women would arise that would threaten the proliferation of a society. Thus was developed the “Alliance theory,” creating the universal prohibition of incest to enforce exogamy. The alliance theory, in which one’s daughter or sister is offered to someone outside a family circle starts a circle of exchange of women: in return, the giver is entitled to a woman from the other’s intimate kinship group. This supposedly global phenomenon takes the form of a “circulation of women” which links together the various social groups in single whole to form society.

Freudo-Marxism

Top row: Wilhelm Reich, Otto Fenichel, Jenny Waelder; middle row: Grete Lehner Bribing, Edward Bribing; bottom row: Edith Buxbaum, Claire Fenichel, Annie Reich.

Ernst Simmel (1882 – 1947

Beginning to teach at the New School in 1939 was Austrian psychologist Wilhelm Reich (1897 – 1957), the father of the Sexual Revolution, who developed the Freudo-Marxist theories of the Frankfurt School.[72] After graduating in medicine from the University of Vienna in 1922, Reich became deputy director of Freud’s outpatient clinic, the Vienna Ambulatorium. Like much of the Frankfurt School’s philosophy, Reich’s ideas were based on Freud’s theory of repressed instincts. Freud also denied the inherent moral nature of the human being. Rather, Freud believed human behavior was motivated by unconscious drives, primarily by the libido or “Sexual Energy.” Freud proposed to study how these unconscious drives were repressed and found expression through other cultural outlets. He called this therapy “psychoanalysis.” Freud’s theory was based on the notion that humans have certain characteristic instincts that are inherent. Most notable are the desires for sex and the predisposition to violent aggression towards authority figures and towards sexual competitors, which both impede the gratification of a person’s instincts.

In his seminal book, Civilization and its Discontents, Freud described what he believed to be a fundamental tension between civilization and the individual. The primary conflict, he suggested, stems from the individual’s quest for instinctual freedom and civilization’s opposite demand for conformity and repression of instincts. Many of humankind’s primitive instincts, such as the desire to kill and the insatiable lust for sexual gratification, are evidently harmful to the well-being of the rest of society. As a result, civilization creates laws to repress these instincts. However, this process, argued Freud, instills perpetual feelings of discontent in its citizens. People develop neuroses because they cannot tolerate the frustration they experience from the inability to fulfill these instincts.

During the 1930s, Reich was part of a general trend among younger analysts and Frankfurt sociologists that tried to reconcile psychoanalysis with Marxism. Reich was among the many psychoanalysts who worked at the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute founded in 1920, before later becoming the Göring Institute, who developed a philosophical combination of Marxist dialectical materialism and Freudian psychoanalysis. These included Ernst Simmel (1882 – 1947), Franz Alexander (1891 – 1964), and Otto Fenichel (1897 – 1946), as well as Erich Fromm. Alexander was a Hungarian-American psychoanalyst who is considered one of the founders of psychosomatic medicine and psychoanalytic criminology. In 1930, Alexander was invited by Robert Hutchins to become its Visiting Professor of Psychoanalysis at the University of Chicago. A prolific writer, he published nearly twenty other articles between “The Castration Complex in the Formation of Character” (1923) and “Fundamental Concepts of Psychosomatic Research” (1943), contributing on a wide variety of subjects to the work of the “second psychoanalytic generation.”[73]

Like his friend Wilhelm Reich, Fenichel, who was a member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, was one of the most influential psychoanalysts in Europe in the 1920s. His Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis is still an essential guide to basic psychoanalytic concepts.[74] Among some of the subjects he contributed to were female sexuality, the feeling of triumph, and the antecedents of the Oedipus complex. One member of the Berlin group of Marxist psychoanalysts around Reich was Erich Fromm, who later brought Freudo-Marxist ideas into the exiled Frankfurt School led by Horkheimer and Adorno. Fromm contended that Freud was one of the “architects of the modern age,” along with Einstein and Marx, but considered Marx both far more historically important than Freud and a finer thinker.[75]

It was Simmel who had diagnosed Princess Alice of Battenberg—the mother Elizabeth II’s husband Prince Philip, and a student of Keyserling’s School of Wisdom—with schizophrenia in 1930, after she had reported communicating with Christ and Buddha.[76] Alice was then forcibly removed from her family and placed in Ludwig Binswanger’s sanatorium in Kreuzlingen, Switzerland. Binswanger also worked closely with Freud, as well as such as Carl Jung and Eugen Bleuler. Binswanger was further influenced by existential philosophy, through the works of Heidegger, Husserl, and Martin Buber. Both he and Simmel consulted Freud, who believed that her delusions were the result of sexual frustration. Freud recommended “X-raying her ovaries in order to kill off her libido.”[77]

Princess Marie Bonaparte (1882 – 1962), sister-in-law of Prince Philip’s mother, Princess Alice of Battenberg, and close friend of Freud

The recommendation to commit Alice had come from her sister-in-law, Princess Marie Bonaparte (1882 – 1962), a great-grandniece of Emperor Napoleon I of France, a distinguished member of the Société Psychanalytique de Paris, who was also a close friend of Freud. Marie was married to the brother of brother of Alice’s husband, Prince George of Greece and Denmark (1869 – 1957). George and Andrew’s father was George I of Greece, the son of Christian IX of Denmark and Louise of Hesse-Kassel, a friend of Comtesse de Keller who married Alexandre Saint-Yves d’Alveydre, the founder of synarchism. Their mother was Olga Constantinovna of Russia, granddaughter of Tsar Nicholas I, a niece of Tsar Alexander II and first cousin of Tsar Alexander III. In 1891, George accompanied his cousin the future Nicholas II on his voyage to Asia, and saved him from an assassination attempt in Japan, in what became known as the Otsu Incident.

Prince Valdemar of Denmark (with newspaper) and his nephew Prince George of Greece and Denmark

George, however, was in love with his uncle, Prince Valdemar of Denmark, George I of Greece’s brother. Marie had many affairs, including with Freud’s disciple Rudolph Loewenstein as well as Aristide Briand, her husband’s aide-de-camp Lembessiss. However, Marie suffered from what was referred to as “frigidity.” Romanian modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuș created a scandal in 1919 when he represented Marie as a large phallus which he titled “Princess X,” symbolizing her obsession with the penis and her lifelong quest to achieve vaginal orgasm, with the help of Freud. Marie published her research results under the pseudonym A.E. Narjani, presenting her theory of frigidity, having measured the distance between the vagina and the clitoral glans in 200 women. Marie had three unsuccessful surgeries performed on her clitoris to try and cure her frigidity. In 1925, Marie consulted Freud for treatment. Based on her interpretation of the Oedipus complex, Marie wondered if incest might be the answer to her problems. She asked Freud is she should have sex with her son to achieve orgasm, but Freud apparently advised against.[78] It was to Marie that Freud famously remarked, “The great question that has never been answered and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is ‘What does a woman want?’”[79]

Marie’s wealth contributed to the popularity of psychoanalysis, and enabled Freud’s escape from Nazi Germany. In London in 1938, Ernest Jones, the then president of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA), used his personal acquaintance with the Home Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, to expedite the granting of permits for Freud and his family and persuaded the president of the Royal Society, Sir William Bragg, to write to Lord Halifax, requesting that diplomatic pressure be applied in Berlin and Vienna on Freud’s behalf. Freud, his wife Martha, and daughter Anna left Vienna on the Orient Express on June 4, arriving in Paris the following day, where they stayed as guests of Marie, before travelling overnight to London. Among those who visited Freud in London were Salvador Dalí, Stefan Zweig, Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf, and H.G. Wells. Representatives of the Royal Society called for Freud, who had been elected a Foreign Member in 1936, to sign himself into membership.[80]

Wilhelm Reich and the orgone accumulator.

In 1929, Reich and his wife Annie Pink visited the Soviet Union on a lecture tour, and returned ever more convinced of the link between sexual and economic oppression, and of the need to integrate Marx and Freud.[81] Reich was the author of several influential books, including The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933) and The Sexual Revolution (1936). The Mass Psychology of Fascism explores how fascists come into power and explains their rise as a symptom of sexual repression. In it, Reich also speculates that matriarchy is the only genuine family type of a “natural society.” The Sexual Revolution, whose original subtitle was “for the socialist restructuring of humans,” analyzes what Reich considered a crisis of the “bourgeois sexual morality. Reich is regarded as one of the most radical figures in the history of psychiatry. It was after he arrived in the United States that he coined the term “orgone,” a word derived from a combination of “orgasm” and “organism,” which he used to refer to a primordial cosmic energy he believed he had discovered and which others referred to as “God.” In 1940, he started building “orgone energy accumulators,” devices that his patients sat inside to harness the reputed health benefits, leading to newspaper stories about “sex boxes” that cured cancer.

Sex Symbol

Marilyn Monroe (nee Norma Jean Baker)

Dr. Ernst Kris (1900 –1957)

To the Freudo-Marxists, because history seen not as a class struggle, but a fight against repression of our “instincts,” their mission was to combat authoritarianism through sexual liberation. Actress and “sex symbol” Marilyn Monroe would undergo psychoanalysis regularly from 1955 until her death, with psychiatrists Margaret Hohenberg (1955–57), Anna Freud (1957), her friend Marianne Kris (1957–61), and Ralph Greenson (1960–62), who were closely associated with the Freudo-Marxist tradition. Ernst Kris (1900 –1957) was an Austrian psychoanalyst and art historian, who worked with Freud and became a member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. In 1927, Kris married Marianne Rie, the daughter of a friend of Freud, Oscar Rie. Marianne gained a medical degree in Vienna in 1925, and did further study in Berlin, where at Freud’s recommendation she was psychoanalyzed by Franz Alexander. Freud called Marianne his “adopted daughter,” and together the Freuds and the Krises fled the Nazis and went to London in 1938. Marianne and Ernst subsequently continued to New York, where she developed a private practice specializing in the clinical aspects of Freudian child psychoanalysis. In 1940, Ernst Kris became a visiting professor at the New School for Social Research, where he founded the Research Project on Totalitarian Communication alongside Hans Speier (1905 – 1990), a German-American sociologist who worked with the United States Government as a Germany expert both during and after World War II. In 1945, Kris co-founded the journal The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child with Anna Freud and Princess Marie Bonaparte.

Marianne Kris (center)

Marilyn’s psychiatrist at the time of her death was Ralph R. Greenson (1911 – 1979), who studied medicine in Switzerland and was analyzed by Wilhelm Stekel, a controversial student of Freud, as well Otto Fenichel and Frances Deri (1880 – 1971) in Los Angeles. Before emigrating from Austria in 1936, Deri, who was born in Austria, worked as a midwife in Germany and then trained as an analyst in the team of Freudian Marxists that included Fenichel, Erich Fromm, Wilhelm Reich, Ernst Simmel and others. Having trained and become politicized together in Berlin and Vienna, these psychoanalysts were dispersed internationally by the rise of the Nazis, most settling in the United States and England where they all became influential teachers. Deri published articles on insomnia and sublimation, as well as contributing to the analysis of coprophilia, and to the fantasy of being part of the partner’s body in sexual submission.[82] Emigrating to the United States to escape Hitler in 1934, Simmel settled in Los Angeles, where, with Fenichel, he was a founding member of the Los Angeles Psychoanalytic Society and Institute (LAPSI). One of Simmel’s notable contributions was made in the 1946 anthology on Anti-Semitism, based on the contributions to a 1944 symposium held in San Francisco by Adorno, Fenichel, and Max Horkheimer among others.

Deri, who had a passion for cinema, became associated with the LAPSI, and specialized in analyzing actors and provided guidance to Greenson.[83] Greenson was recommended to Marilyn by his good friend Marianne Kris. When Marilyn wanted a new psychoanalyst to replace Hohenberg, she telephoned Anna Freud who recommended Marianne Kris. Greenson also had other famous clients, including Tony Curtis, Frank Sinatra, and Vivien Leigh. Greenson and his wife, Hildi Greenson, were good friends with Anna Freud, Fawn Brodie and Margaret Mead. Greenson cultivated a reputation as a popular lecturer, with titles including “Emotional Involvement,” “Why Men Like War,” “Sex Without Passion,” “Sophie Portnoy Finally Answers Back,” “The Devil Made Me Do It, Dr. Freud,” and “People in Search of a Family.” In “Special Problems In Psychotherapy With The Rich and Famous,” Greenson described his experiences with Marilyn, a part of his professional and personal life that became an obsession.[84]

Monroe had started undergoing psychoanalysis under the recommendation of Lee Strasberg (1901 – 1982), “father of method acting in America,” who believed an actor must confront their emotional traumas and use them in their performances. Tragically, at the age of fifteen, Marilyn’s mother, Gladys Pearl Baker (née Monroe), married John Newton Baker, who had been abusive. Gladys successfully filed for divorce and sole custody in 1923. In 1933, Gladys bought a house in Hollywood which they shared with actors George and Maude Atkinson, who may have sexually abused Marilyn.[85] In January 1934, Gladys had a mental breakdown, was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and committed to the Metropolitan State Hospital. Marilyn became a ward of the state, but ended up living for a time with her mother’s friend, Grace Goddard, and her husband Erwin “Doc” Goddard who also molested her.[86] Nevertheless, Grace had a passion for Marilyn to become a movie star.[87]

Dr. Ralph R. Greenson, Marilyn’s “Svengali”

Marilyn’s housekeeper Eunice Murray, educated at Swedenborgian school and married to son of Swedenborgian minister

Marilyn began visiting Greenson seven days a week at his home, and eventually twice a day. Greenson eventually arranged for a live-in nanny named Eunice Murray, who had been educated at a Swedenborgian school, and had been married to the son one of a Swedenborgian minister, John Murray.[88] As everyone in Marilyn’s entourage became convinced that Greenson and Murray were the source of her troubles. Veteran makeup artist Allan Snyder described Eunice as “a very strange lady. She was put into Marilyn’s life by Greenson, and she was always whispering—whispering and listening. She was this constant presence, reporting everything back to Greenson, and Marilyn quickly realized this.”[89] Murray was also responsible for regularly administered dangerous doses of barbiturates, which she called “vitamin shots.”[90] Greenson told Marilyn’s agent, Charles Feldman, that he would “be able to get his patient to go along with any reasonable request and although he did not want us to deem his relationship as a Svengali one, he in fact could persuade her to anything reasonable that he wanted.”[91]

At Marianne Kris’ suggestion, Monroe first admitted herself to the Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic in New York, a year before she apparently committed suicide in August 1962. She was placed on a ward meant for severely mentally ill people with psychosis, where she was locked in a padded cell. Monroe was finally able to leave the hospital with the help of her ex-husband Joe DiMaggio, and moved to the Columbia University Medical Center, spending a further twenty days there. Marianne later confessed that her choice of hospital was a mistake.[92] Nevertheless, Marianne was one of the main beneficiaries in Marilyn’s will. When Marianne died, she bequeathed this legacy to a child therapy center at the London Tavistock Center Clinic, originally founded by Anna Freud. This money has been used to fund the Monroe Young Family Centre.[93]

Psycho Analysis

Dr. Bertram D. Lewin (1896 – 1971)

Ernst Kris, along with psychoanalyst Walter C. Langer, and Dr. Bertram D. Lewin (1896 – 1971) of the New York Psychoanalytic Institute, had collaborated with American psychologist Henry A. Murray on a report commissioned in 1943 by William “Wild Bill” Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA, titled “Analysis of the Personality of Adolph Hitler.” In Berlin in the 1920s, Lewin had a training analysis with Franz Alexander, of the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute. Lewin published his first analytic article in 1930, followed by others on subjects ranging from diabetes and claustrophobia to the body as phallus. The main focus of his interest was manic states, which he saw as characterized by fleeting identifications with a multiple of outside figures.[94] Murray, the Director of the Harvard Psychological Clinic, would go on to become a colleague of Timothy Leary at Harvard University, where from 1959 to 1962, he conducted a series of psychologically damaging experiments on undergraduate students, one of whom was Ted Kaczynski, later known as the Unabomber.

Henry A. Murray, who later dosed the Unabomber with LSD

Murray was a recruit to the sex-cult of his friend Carl Jung. Murray married in 1916 at age 23, but after seven years of marriage, in 1923, then biochemist at Rockefeller University in New York, he met and fell in love with Christiana Morgan. In a new Hebrew-language biography of Chaim Weizmann, Motti Golani and Jehuda Reinharz cite documents showing that in 1921 Christiana Morgan had a liaison with Weizmann.[95] As Murray did not want to leave his wife, he experienced a serious conflict, after which Morgan advised him to visit Jung in 1927, and upon whose advice they became lovers “to unlock their unconscious and their creativity.”[96] As described by Richard Noll:

Christiana Morgan, mistress of Henry A. Morgan and Chaim Weizmann

In later years, mimicking Jung, Murray built his own “Tower” in Massachusetts, which he and Morgan decorated with their own mystical paintings and drawings. They believed that they were performing important spiritual work for all humankind and starting a new form of religion. They created their own new pantheon of gods, in which the sun symbolized the highest deity. They painted the sun in the center of the ceiling of the main ritual room of their tower. Besides orgies of alcohol and sex, they also indulged in detailed magical rituals that involved recitations from Jung’s works.[97]

Murray diagnosed Hitler as exhibiting all the classical symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia: “hypersensitivity, panics of anxiety, irrational jealousy, delusions of persecution, delusions of omnipotence and messiahship.”[98] The report also concluded that Hitler was a particularly extreme case of the “counteractive type,” which was most likely the result of some childhood trauma. The report describes the type as:

…marked by intense, stubborn efforts (1) to overcome early disabilities, weaknesses and humiliations (wounds to self-esteem, and sometimes insults to pride. This is achieved by means of an Idealego Reaction Formation which involves (i) the repression and denial of the inferior portions of the self, and (ii) strivings to become (or to imagine one has become) the exact opposite, represented by an Idealego, or image of a superior self successfully accomplishing the once-impossible feats and thereby curing the wounds of pride and winning general respect, prestige, fame.[99]

According to the report, Hitler’s underlying sense of inferiority is compensated for by seeking to identify himself with attributes that are the very opposite of himself: brute strength, purity of blood and fertility. He was not physically fit. Afraid of his father, his behavior was “annoyingly subservient” to his superior officers, according to Murray. Although he spent four years in the army, he never rose above the rank of corporal. He suffered from frequent emotional collapses, which included screams and tears, and suffered bouts of deep depression. Sexually, according to the report, Hitler was “a full-fledged masochist,” which the authors attribute to an “unconscious need for punishment.” The report, titled “Analysis of the Personality of Adolph Hitler,” ultimately concluded:

In speaking before crowds he is virtually possessed. He clearly belongs to the sensational company of history-making hysterics, combining, as he does, some of the attributes of the primitive shaman, the religious visionary, and the crack-brained demagogue—consummate actors, one and all.

Murray helped with another psychological profile of Hitler for the OSS prepared by psychoanalyst Walter C. Langer in 1943, which claims Hitler not only exhibited homosexual tendencies, but was also impotent. Langer concludes, “Unable to demonstrate male power before a woman, he is impelled to compensate by exhibiting unsurpassed power before men in the world at large.”[100] During his years in Vienna, Hitler lived a life of poverty and filth, and remarked, “I enjoy nothing more than to lie around while the world defecates on me.” He resided in a flophouse known to be inhabited by homosexuals, and it was likely for this reason that he was listed on the Vienna police record as a “sexual pervert.”[101] Because Hitler suffered from an irrational dread that associated sexuality with excrement, Hitler was a coprophile, enjoying sexual arousal from feces, a “pleasure” supposedly repressed, according to Freud, in the so-called “anal stage” of development. Langer attributes this coprophilic tendency to an Oedipal fixation due to the overly repressive tendencies of Hitler’s mother.

Gregor Strasser, along with Ernst Hanfstaengl, Hermann Rauschning, Princess Stephanie von Hohenlohe, Friedelinde Wagner, and Kurt Ludecke, were important sources for the OSS report. In September 1945, at the end of the war, a list was discovered in Berlin, known as the Nazis’ Black Book which showed that the Cliveden Set’s members were all to be arrested as soon as Britain was invaded. The list was produced in 1940 and prepared by the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA) under Reinhard Heydrich, as part of the preparation for the proposed invasion of Britain codenamed Unternehmen Seelöwe (“Operation Sea Lion”). The list included numerous prominent British residents to be arrested, including Sigmund Freud, H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley and Ernst Hanfstaengl. Hanfstaengl fell completely out of Hitler’s favor after 1933, and was denounced by his close friend Unity Mitford. Hanfstaengl made his way to Switzerland, then on to Britain and ended up in a prison camp in Canada after the outbreak of the World War II. In 1942, Hanfstaengl was turned over to the US and worked for President Roosevelt, revealing vital information on the Nazi leadership. Hanfstaengl provided 68 pages of information on Hitler alone, including personal details of Hitler’s private life, and he helped Murray develop his profile of Hitler.

[1] Report, Joint Legislative Committee Investigating Seditious Activities, State of New York (April 24, 1920), p. 1119.

[2] Ibid., pp. 1120-21.

[3] Zygmund Dobbs. Keynes at Harvard: Economic Deception As a Political Credo 9 (Veritas Foundation, 1962).

[4] Steven M. Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within: Comparative Perspectives on “Redemption Through Sin.” The Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, Vol. 6, 199., p. 52.

[5] Martin Jay. The Dialectical Imagination: A History of the Frankfurt School and the Institute for Social Research, 1923-1950 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), p. 107.

[6] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 54.

[7] Jurgen Habermas. “The German Idealism of the Jewish Philosophers” (Essays on Reason, God, and Modernity).

[8] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 37.

[9] Gershom Scholem. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism; cited in Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 37.

[10] Zohar Maor. “Moderation from Right to Left: The Hidden Roots of Brit Shalom.” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Winter 2013), pp. 79-108.

[11] Maor. “Moderation from Right to Left,” p. 86.

[12] Sternhell. The Founding Myths of Zionism.

[13] Gershom Scholem. “Politik des Zionismus,” in Tagebücher, 2: 626; cited in Sternhell. The Founding Myths of Zionism, p. 90.

[14] Sternhell. The Founding Myths of Zionism, p. 90.

[15] Scholem. Du Frankisme, p. 39; cited in Marsha Keith Schuchard. “Dr. Samuel Jacob Falk,” p. 220.

[16] Elisabeth Hamacher. Gershom Scholem und die Allgemeine Religionsgeschichte (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1999), p. 60. Cited Hakl. Eranos, p. 155.

[17] Yedioth Hayom (December 5, 1947); cited in Hakl. Eranos, p. 156.

[18] Hakl. Eranos, p. 156–158.

[19] Hakl. Eranos, p. 158.

[20] Steven B. Smith. “Gershom Scholem and Leo Strauss: Notes toward a German-Jewish Dialogue.” Modern Judaism, Vol 13, No. 3 (Oxford University Press, Oct., 1993).

[21] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 37.

[22] Ibid., p. 41.

[23] Ibid., p. 42.

[24] David Ohana. Modernism and Zionism (New York: Palsgrave Macmillan, 2012) p. 73.

[25] Erich Fromm. Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx & Freud (London: Sphere Books, 1980), p. 11.

[26] Népszava (April 15, 1919). Retrieved from: https://adtplus.arcanum.hu/hu/view/Nepszava_1919_04/?pg=0&layout=s

[27] Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Frankfurt School.” Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Frankfurt-School. Accessed 10 January 2022.

[28] Joel Whitebook. “The Marriage of Marx and Freud: Critical Theory and psychoanalysis.” in Fred Leland Rush (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Critical Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2004). pp. 75.

[29] Raymond Geuss. The Idea of a Critical Theory: Habermas and the Frankfurt school (Cambridge University Press, 1981). p. 58.

[30] Richard Wollin. “Walter Benjamin Meets the Cosmics.” Retrieved from https://media.law.wisc.edu/m/ndkzz/wolin_revised_10-13_benjamin_meets_the_cosmics.doc; Georg Lukacs. The Destruction of Reason (London: Merlin, 1980), p. 1.

[31] Habermas, “Consciousness-Raising or Rescuing Critique,” in On Walter Benjamin: Critical Essays and Recollections, ed. Gary Smith (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1988), 113.

[32] Wollin. “Walter Benjamin Meets the Cosmics.”

[33] Nitzan Lebovic. “The Beauty and Terror of "Lebensphilosophie": Ludwig Klages, Walter Benjamin, and Alfred Baeumler.” South Central Review, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Spring, 2006), pp. 24.

[34] Wollin. “Walter Benjamin Meets the Cosmics.”

[35] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 54.

[36] Bryan S. Turner. “Sovereignty and Emergency Political Theology, Islam and American Conservatism.” Theory, Culture & Society 2002 (SAGE, London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi), Vol. 19(4): 103–119.

[37] Edward Shils. “Robert Maynard Hutchins.” The American Scholar, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Spring 1990), p. 223.

[38] Jay. The Dialectical Imagination, p. 39.

[39] Georges Bataille. “Nietzsche and Fascists.” Acéphale (January 1937); Pierre Prévost. Georges Bataille et René Guénon (Jean Michel Place, Paris).

[40] Michael Weingrad. “The College of Sociology and the Institute of Social Research.” New German Critique, No. 84 (Autumn, 2001), pp. 129.

[41] Jeffrey Mehlman, “Parisian Messianism: Catholicism, Decadence and the Transgressions of George Bataille.” History and Memory l3.2 (Fall/ Winter 2001): 113-33.

[42] Jillian Becker. “The French Pandemonium, Part Two.” The Darkness of This World (November 23, 2014).

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Donald Traxler. The Light of Sex: Initiation, Magic and Sacrament (Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2011), pp. 1–2.

[46] Hugh B. Urban. Secrecy: Silence, Power, and Religion (University of Chicago Press, 2021), p. 82.

[47] Georges Bataille. “Introduction.” In Stoekl, Allan. Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927-1939 (University of Minnesota Press, 1985). pp. xx–xxi.

[48] Bataille. “The Sacred Conspiracy.” Visions of Excess, p. 179; cited in Michael Weingrad. “The College of Sociology and the Institute of Social Research.” New German Critique, No. 84 (Autumn, 2001), p. 134.

[49] Steven M. Wasserstrom. Religion after Religion: Gershom Scholem, Mircea Eliade, and Henry Corbin at Eranos (Princeton University Press, 1999) p. 219.

[50] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 44.

[51] Klossowski. “The Marquis de Sade and the Revolution.” The College of Sociology, p. 222; cited in Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 44.

[52] Michael Weingrad. “The College of Sociology and the Institute of Social Research.” New German Critique, No. 84 (Autumn, 2001), p. 152.

[53] Jacob Golomb & Robert S. Wistrich. Nietzsche, Godfather of Fascism?: On the Uses and Abuses of a Philosophy (Princeton University Press, Jan. 10, 2009), p. 6.

[54] October, 1986, pp. 45

[55] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 55.

[56] Horkheimer & Adorno. Dialectic of Enlightenment; cited in Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 49.

[57] Cited in Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 49.

[58] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 50.

[59] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 51.

[60] Hugh B. Urban. Tantra: Sex, Secrecy, Politics, and Power in the Study of Religions (University of California Press, 2003), pp. 166–167.

[61] Hakl. Eranos, p. 124.

[62] Hakl. Eranos, p. 162.

[63] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 49.

[64] Hakl. Eranos, p. 82.

[65] Hakl. Eranos, p. 156.

[66] Hakl. Eranos, p. 12.

[67] Hakl. Eranos, p. 120.

[68] Gershom Scholem. “Redeption Through Sin,” The Messianic Idea in Judaism: And Other Essays on Jewish Spirituality, (New York: Schocken, 1971).

[69] F. Chaubet & E. Loyer. “The Ecole-Libre-des-Hautes-Etudes in New York: exile and intellectual resistance (1942-1946).” Revue historique (2000).

[70] Chris Thornhill. Karl Jaspers: Politics and Metaphysics (Routledge, 2002), p. 1.

[71] Chris Knight. Decoding Chomsky: Science and revolutionary politics. (New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2018).

[72] James E. Strick. Wilhelm Reich, Biologist (Harvard University Press, 2015), p. 2.

[73] Ibid. p. 593-4.

[74] Benjamin Harris & Adrian Brock. “Freudian Psychopolitics: The Rivalry of Wilhelm Reich and Otto Fenichel, 1930-1935.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Vol. 66, No. 4 (Winter, 1992), p. 580.

[75] Erich Fromm. Beyond the Chains of Illusion: My Encounter with Marx & Freud (London: Sphere Books, 1980), p. 11.

[76] Hugo Vickers. Alice, Princess Andrew of Greece (St. Martin's Publishing Group, 2013).

[77] D. Cohen. “Freud and the British Royal Family.” The Psychologist, Vol. 26, No. 6, (June 2013).

[78] D. Cohen. “Freud and the British Royal Family.” The Psychologist, Vol. 26, No. 6, (June 2013).

[79] Ernest Jones. The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 2 (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1955), p. 421.

[80] David Cohen. The Escape of Sigmund Freud (JR Books, 2009), pp. 178, 205–07.

[81] Myron Sharaf. Fury on Earth: A Biography of Wilhelm Reich (Da Capo Press 1994), pp. 142–143, 249.

[82] Otto Fenichel. The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis (1946) p. 353, 673.

[83] Michel Schneider. Marilyn’s Last Sessions (Canongate Books, 2011).

[84] Donald Spoto. Marilyn Monroe: The Biography (Cooper Square Press, 2001), p. 425–427.

[85] Donald Spoto. Marilyn Monroe: The Biography (Cooper Square Press, 2001), pp. 33–40

[86] Lois Banner. Marilyn: The Passion and the Paradox (Bloomsbury, 2012), pp. 62–64.

[87] Lois Banner. Marilyn: The Passion and the Paradox (Bloomsbury, 2012), p. 427.

[88] Ibid., p. 479–480.

[89] Ibid., p. 482.

[90] Ibid., p. 492.

[91] Ibid., p. 534.

[92] Ibid., pp. 310–313, 456–459.

[93] Adam Victor. The Marilyn Encyclopedia (Overlook Press, 2012).

[94] Otto Fenichel. The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis (London, 1946) p. 408.

[95] עובד, הוצאת ספרים עם. "עם עובד - האב המייסד / מוטי גולני ויהודה ריינהרץ". www.am-oved.co.il (in Hebrew). Retrieved from https://www.am-oved.co.il/%D7%94%D7%90%D7%91_%D7%94%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%93

[96] Michel Weber. “Christiana Morgan (1897–1967).” in Michel Weber & William Desmond, Jr. (eds.), Handbook of Whiteheadian Process Thought (Frankfurt / Lancaster, Ontos Verlag, 2008), v. II, pp. 465–468.

[97] Richard Noll. The Aryan Christ: The Secret Life of Carl Jung (Random House, 1997), p. 92.

[98] Walter Langer. “Analysis of The Personality of Adolph Hitler.” OSS Confidential (1943).

[99] Ibid.

[100] Henry A. Murray. “Analysis of The Personality of Adolph Hitler.” OSS Confidential (1943).

[101] Walter C. Langer. “A Psychological Analysis of Adolph Hitler His Life and Legend.” Office of Strategic Services (Washington DC, 1943).

Volume Three

Synarchy

Ariosophy

Zionism

Eugenics & Sexology

The Round Table

The League of Nations

avant-Garde

Black Gold

Secrets of Fatima

Polaires Brotherhood

Operation Trust

Aryan Christ

Aufbau

Brotherhood of Death

The Cliveden Set

Conservative Revolution

Eranos Conferences

Frankfurt School

Vichy Regime

Shangri-La

The Final Solution

Cold War

European Union