19. The Vichy Regime

Synarchist Pact

The Third French Republic—the system of government adopted in France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War—declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, after the German invasion of Poland. The Germans launched their invasion of France on May 10, 1940. Within days, it became clear that French military forces were overwhelmed and that collapse was imminent. Marshal Philippe Pétain (1856 – 1951) signed the Armistice of 22 June 1940, which divided France into occupied and unoccupied zones. Northern and western France, that encompassed all English Channel and Atlantic Ocean, was occupied by Germany, and the remaining southern portion of the country came under the control of the French government with the capital at Vichy under Pétain, a General who was viewed as a national hero in France because of his outstanding military leadership in World War I. Officially independent, it adopted a policy of collaboration with Nazi Germany.

It was following the suspicious death by suicide, of Pétain’s friend Jean Coutrot (1895 – 1941), on May 19, 1941, by jumping out of a window, that Pétain received a file from Henri Martin, one of the former leaders of La Cagoule terrorist organization, which claimed to expose the existence and activity of a secret society called Mouvement Synarchique d'Empire (MSE).[1] The file denounced the MSE as the origin of the Synarchist Pact, and the secret power network behind the Vichy Regime. This group would have been composed almost exclusively of polytechnics and financial inspectors meeting in a room belonging to the Banque Worms bank. In July, a report was submitted by Henri Chavin, at the time the Director of Sûreté nationale, to the French Minister of the Interior, which presented the synarchist conspiracy as an attempt by international capitalism to “subject the economies of different countries to a single, undemocratic control exercised by high banking groups.”[2] As revealed in the report, it was this same group which gave rise to the Cagoule.

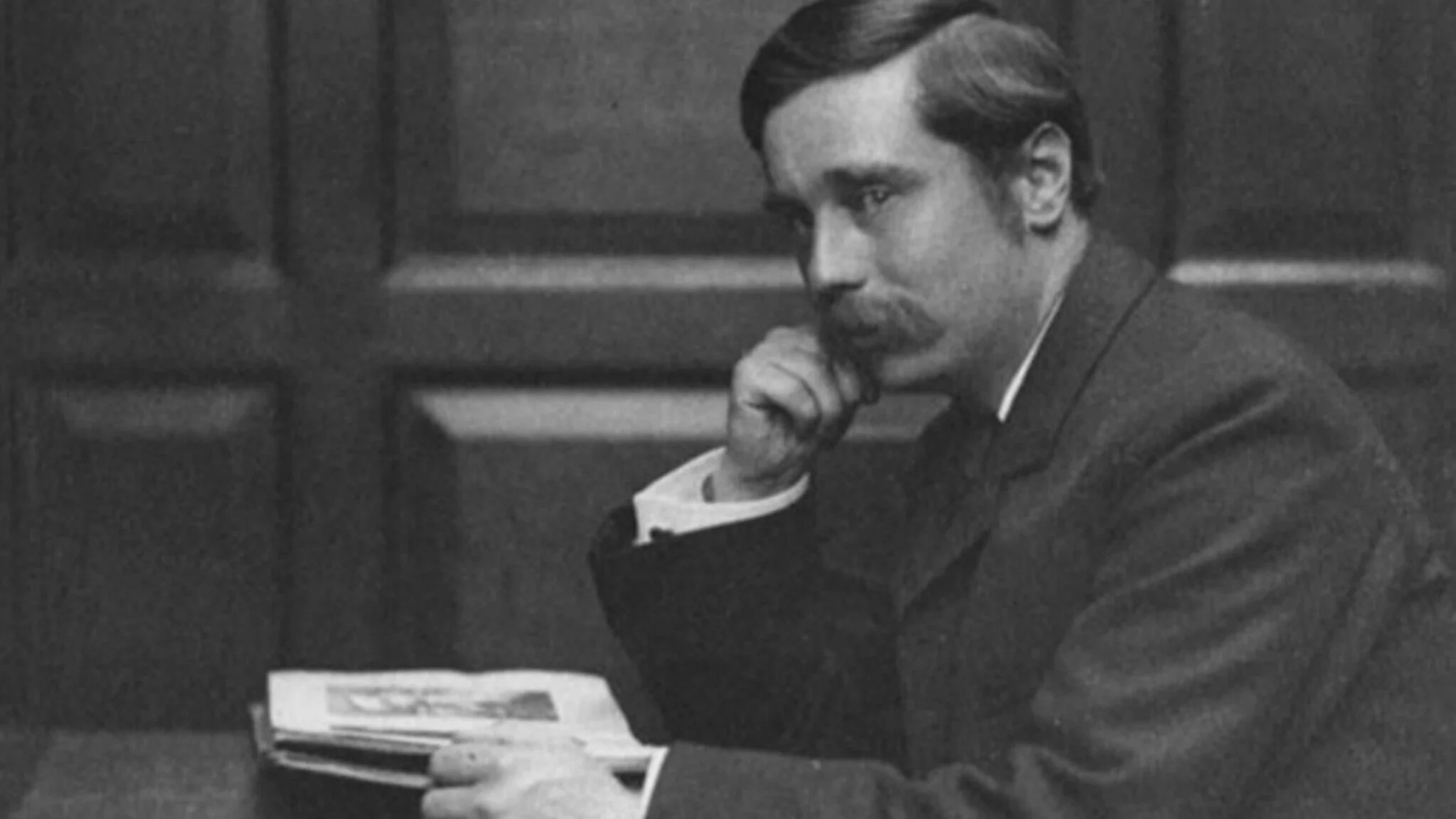

According to the Chavin Report, Coutrot, an engineer educated at the École Polytechnique, who had been associated with Action française,[3] travelled several times to England in 1938 and 1939 to meet with Aldous Huxley, who is described as “pro-national-socialist.”[4] In 1936, Huxley and Coutrot had founded the Center for the Study of Human Problems (CSHP), which was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation.[5] According to the Chavin Report, the CSHP was one of several synarchist fronts, which were all set up for the purpose of recruiting members to the Mouvement Synarchique d’Empire (MSE), of which Coutrot was the leader.[6] Also affiliated with the CSHP was Huxley’s friend and fellow Fabian, H.G. Wells. In Open Conspiracy: Blue Prints for a World Revolution (1928), Wells wrote:

…will appear first, I believe, as a conscious organization of intelligent and quite possibly in some cases, wealthy men, as a movement having distinct social and political aims, confessedly ignoring most of the existing apparatus of political control, or using it only as an incidental implement in the stages, a mere movement of a number of people in a certain direction who will presently discover with a sort of surprise the common object toward which they are all moving… In all sorts of ways they will be influencing and controlling the apparatus of the ostensible government.[7]

Aldous Huxley (1894 – 1963), described in the Chavin Report as “pro-national-socialist.”

Jean Coutrot (1895 – 1941), reputed author of the Synarchist Pact

The goal of the synarchists is the creation of a united Europe, as part of the fulfilment of the vision advanced by Saint-Yves d’Alveydre, a call for which appears on the first page of his first book on synarchy, Keys to the East. The need for Europe to unite under a single, synarchist state, according to Saint Yves, is prompted by the rise of Islam as a world power, which threatens a weak, fragmented, and materialist West. This is despite the fact that Saint-Yves source for synarchy was “Hajji Sharif,” who in actuality was Jamal ud Din al Afghani, the founder of Salafism, which became the underlying doctrine of Islamic terrorism. Influenced by ideas borrowed from Martinism and Plato’s Republic, Saint-Yves envisioned a Federal Europe with a corporatist government, composed of three councils representing economic power, judicial power, and scientific community, of which the metaphysical chamber bound the whole structure together. As part of this concept of government, Saint-Yves attributed an important role to occult secret societies, which are composed of oracles and who rule the government from behind the scenes, a role once fulfilled by the Rosicrucians.

Coutrot’s MSE was a direct successor of Papus’ Martinist Order. Papus’ death in 1916 had resulted in a schism in the Martinist Order over its involvement in politics. In 1921, those who were loyal disciples of Saint-Yves d’Alveydre established their own temple in Paris and called the Ordre Martiniste et Synarchie (OMS), founded by Victor Blanchard, who was head of the secretariat of the Chamber of Deputies of the French Parliament. Blanchard, who claimed to be the legitimate successor of Papus as head of the Martinist Order, was the Grand Master of the Brotherhood Polaires and would become of the three Imperators of FUDOSI, along with AMORC founder Harvey Spencer Lewis and Émile Dantinne a member of Péladan’s Order of the Temple and the Grail and of the Catholic Order of the Rose-Croix. The activists OMS had established the Synarchic Central Committee in 1922, designed to pull in promising young civil servants and “younger members of great business families.”[8] The Committee soon became the Mouvement Synarchique d'Empire (MSE) in 1930, with the aim of abolishing parliamentarianism and replacing it with synarchy, and was headed by Coutrot.[9]

The activities of the synarchists were also exposed in the French collaborationist daily L’Appel. It was Coutrot’s “strange death” by suicide announced in L’Appel in 1941 of Jean Coutrot, which precipitated a swirl of rumors in the collaborationist press in Paris about a “synarchist conspiracy” that became a massive sensation. According to L’Appel, the synarchist movement was an international in scope, emerging after the Treaty of Versailles of 1919, and which is financed and led by certain groups belonging to the international high finance and banking. It aims essentially to overturn, in all the countries where they exist, parliamentary regimes deemed insufficiently devoted to their interests, and moreover, who are too difficult to manipulate, due to the large number of people whose assistance would need to be secured. It also proposes to replace these governments with authoritarian regimes that are more amenable, in which all powers are concentrated in banking groups specially designated for each country.[10]

In a level of secrecy along Martinist lines, members of the MSE were recruited from elite circles who are expected to enroll new adherents from among their peers. The candidate has no contact with the organization until the day he is invited to join. Then he receives a copy of the “Pacte synarchiste revolutionnaire,” known as the Synarchist Pact. Coutrot owned a copy of the pact and was suspected of being one of its authors. The Synarchist Pact is a hundred-page booklet, bound with a sealed gold band, which bears two numbers, one for identifying himself and one for his sponsor. About the organizational set-up and the policy-making bodies, he is told nothing. Every precaution is taken to ensure secrecy.[11] The document opens with the following warning:

All illicit possession of the present document opens one to sanctions without foreseeable limits, whatever the channel by which it was received. In such a case, it is best to burn it and at no point to speak of it.[12]

The Synarchist Pact argued, based on the “four orders that correspond to the Hindu caste system,” that a “division of people into order is natural and conforms with tradition,” and set out a program for “invisible revolution” or “revolution from above,” meaning taking over a state from within by infiltrating high offices. The synarchists were op to the parliamentarian of the Third Republic as a British import. Each nation would need the political system appropriate to it: “Bolshevism currently suits the Eurasian peoples, as Fascism the Italian people, Nazism the Germanic people, parliamentarian the British people.” The first step was to take control of France, before creating the “European Union.”[13] The “empire,” after which the MSE is named, is defined as “the organic grouping of major nations,” of which there are to be five: a federation of pan-American nations with the exception of Canada; a pan-Eurasian federation consisting of the Soviet Union, including all its Central Asian republics, but excluding Finland and the Baltic states; the pan-European-African federation, consisting of Western Europe, and the African continent excluding the British colonies. China and Japan head the pan-Asiatic federation.[14]

Banque Worms

Admiral William D. Leahy (1875 – 1959)

According to L'Appel, the synarchists had connections in Britain and in the United States, especially with the American DuPont and Ford interests. Irenee du Pont (1876 – 1963), president of the DuPont company and the most imposing and powerful member of the dynasty, was an admirer of Hitler and Mussolini. Despite the fact that he had Jewish blood, he advocated a race of supermen to be achieved through eugenics policies. By 1915, Du Pont had begun to absorb General Motors. The du Pont company, and particularly GM, was a major contributor to Nazi military effort. Du Pont’s GM and Rockefeller’s Standard Oil of New Jersey collaborated with IG Farben, the Nazi chemical cartel, to form Ethyl GmbH.[15]

According to the newspaper, the synarchists had access to the American embassy in Vichy, then headed by Admiral William D. Leahy, a close friend President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[16] Banks such as Rothschild, Lazard, Banque d’Indochine or Banque Worms therefore financed many fascinating small groups in the inter-war period.[17] Michael Sordet, in “The Secret League of Monopoly Capitalism,” published in the scholarly Swiss review, Schweiner Annalen, describes the synarchist movement in Europe as “The representatives of international high finance,” who helped bring fascism to power in Germany and who contributed to the defeat of France and the rise of Petain.[18]

Hypolite Worms (1889 – 1962)

French historian Annie Lacroix-Riz has identified Hypolite Worms, and Jacques Barnaud, the director of Banque Worms, and original founders of the MSE.[19] The MSE’s leaders were mainly executives of Banque Worms and members of Opus Dei involved in the Vichy regime’s collaboration with the Nazis. After the Banque de France, Banque Worms was the second most powerful bank in the country. Banque Worms was founded in 1928 by Hypolite Worms as a division of Worms & Cie, which founded by his grandfather in 1910. The Woms banking dynasty were one of sixteen Jewish families that belonged to the haute bourgeoisie d’affaires, including Oppenheim and Dupont.[20] There was also a Worms branch of the Rothschilds, after Charlotte Jeanette Rothschild, the daughter of the dynasty’s founder, Mayer Amschel Rothschild, married Benedikt Moses Worms (1801 – 1882).

Les Veilleurs

Cover illustration of La Synarchie. Le mythe du complot permanent by Olivier Dard

Vivien Postel du Mas

René Adolphe Schwaller de Lubicz (1887 – 1961)

While the leadership of the MSE remained a secret, the names of two of the authors the Synarchist Pact were revealed: Vivien Postel du Mas and Jean Coutrot.[21] Postel du Mas along with Jeanne Canudo were both behind the founding of the MSE.[22] Postel du Mas was also a member of the French Theosophical Society, and around 1936, founded the Theosophical branch Kurukshétra based on ideas of the pro-German right.[23] It is this branch that supposedly gave birth in 1937 to the Synarchist Empire Movement. Both du Mas and his associate Canudo—remembered as an energetic campaigner for European unity—belonged to Guénon’s Brotherhood of the Polaires.[24]

Postel du Mas was also involved a group called Les Veilleurs (“the Watchers”) founded by a French occultist René Adolphe Schwaller de Lubicz (1887 – 1961) who was also a student of Theosophy and Saint-Yves d’Alveydre’s synarchy.[25] Despite being born of a Jewish mother, de Lubicz along with other members of the Theosophical Society broke away to form an occult right-wing and anti-Semitic organization, which he called Les Veilleurs, to which the young Rudolf Hess also belonged.[26] Some have argued it was possible that Hess borrowed ideas from the Watchers which he could have introduced to the Thule Society. As Joscelyn Godwin points out, there’s even a phonetic link between “Thule” and the name of the Watchers’ inner circle, “Tala.”[27]

Still another member of de Lubicz’ Watchers was Julien Champagne, who some believe was the true identity of Fulcanelli, the mysterious French alchemist and author of Le Mystère des Cathédrales about the sacred architecture of the Templars. However, according to Pierre Plantard’s collaborator in the Priory of Sion myth, Paul Le Cour, Fulcanelli was none other than the alchemist Eugène Canseliet.[28] Canseliet had also been a member of the Brotherhood of Heliopolis with Schwaler de Lubicz.[29] Fulcanelli was a confidant of de Lubicz and collaborated with him in several alchemical experiments. However, De Lubicz claimed that Fulcanelli had not only plagiarized his ideas on the symbolism of cathedrals, but had also attempted to make gold without fully understanding the procedure. It has also been suspected that de Lubicz himself was Fulcanelli.[30]

Jean Cocteau (1889 – 1963), purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion

Subsequently, de Lubicz went to Egypt, where he spent years studying the temple at Luxor. Le Temple de l’Homme, published in 1958, was his exposition of the secret meaning of Pharaonic architecture. Jean Cocteau,, another purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion, was also in contact with Schwaller de Lubicz, with whom he shared numerous synarchist ties. Cocteau, who stayed with the Lubiczes in Egypt, said, “I am a heretic by birth—may I be forgiven. I kneel down before the Lubicz family.”[31]

André VandenBroeck, a student of de Lubicz, learned of the connection of Postel du Mas and Canudo to the Watchers and remarked that he had heard about “the secret society that is said to have been a gray eminence behind the French governments of the 1930s and early 1940s, and that is believed in some quarters to wield power in France even to this day,” and he adds that du Mas’ Synarchic Pact “made its way in the corridors of the Third Republic and during the Occupation.”[32]

Maurice Girodias (1919 – 1990)

An important witness to their synarchism was the Parisian publisher Maurice Girodias. Girodias was born Maurice Kahane in Paris, the son of a Jewish father and Catholic mother. Kahane was the founder of the Obelisk Press, which Girodias would later take over, and which published erotica as well as works by Henry Miller, James Joyce and Anaïs Nin. Girodias described Canudo as the “occult brain behind the radical and socialist parties, a militant adventuress of feminine Freemasonry and the cause of women in general.”[33] Girodias was involved with an esoteric society that met at Postel du Mas’ apartment to hear the “secret masters” speaking through a trance medium. Girodias first became intrigued at lectures by Krishnamurti at the Theosophical Society in 1935, where Postel du Mas and Canudo led a group dressed as Templar knights wearing red capes and riding boots. [34]

X-Crise

Pontigny Abbey, a Cistercian monastery located in Pontigny, France, founded in 1114 by Hugh of Mâcon, its first abbot joined his friend and kinsman of Bernard of Clairvaux at the Council of Troyes that granted official recognition to the Templars.

Denis de Rougemont (1906 – 1985)

The CSHP was one of many groups founded by Coutrot who met at the Pontigny Abbey—one of the four daughter houses of Cîteaux Abbey, along with Morimond, La Ferté and Clairvaux—founded in 1114 by Hugh of Mâcon, who later joined his friend St. Bernard at the Council of Troyes in 1128 to officially approve and endorse the Templars on behalf of the Church. In 1909, the abbey was purchased by the philosopher Paul Desjardins, who from 1910 to 1914 held meetings there every year, known as “Decades of Pontigny,” where the intellectual elite of Europe met including Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, T.S. Eliot, Thomas Mann, Heinrich Mann and Nikolai Berdyaev.[35] Between 1922 and 1939, Desjardins reorganized the conferences to evaluate the future of Europe, bringing together annually such notables as and Denis de Rougemont.[36]

According to the Chavin Report, the CSHP was one several groups, such as X-Crise, the Comité national de l'organisation française (CNOF), Centre national de l’organization scientifique du travail (COST), the Groupements non-conformistes, and the Institute for Applied Psychology, that Coutrot had founded as synarchist fronts allegedly for the purpose of recruiting members of the MSE. The Chavin Report also questions the source of Coutrot’s extensive funds. It notes that Coutrot was never paid for his involvement in COST and financed the entire costs of all his groups and their publications himself, though he has severed all business activity since 1936. His annual expenses would have attained at least 300,000 French francs, which is the equivalent today in US dollars of approximately $1.2 million.[37] In 1938 and 1939, Coutrot travelled several times to England, where he met with Aldous Huxley, which the Chavin Report as “pro-national-socialist.”[38]

X-Crise was a French technocratic movement created in 1931 by former students of École Polytechnique (also known by the nickname “X”), where Coutrot had studied engineering, and which included Gérard Bardet and André Loizillon, and whose members included Raymond Abellio, Louis Vallon, Jules Moch and Alfred Sauvy, who as head of the INED demographic institute after World War II and coined the term “Third World.” Abellio, who would go on to play an important role in the post-War French New Right and the formulation of the Priory of Sion mythos, explained that, “we wanted to make X-Crise the crucible of a mysterious occult society called ‘Synarchy’ and of which Jean Coutrot was then designated as the promoter.”[39]

Aimee Moutet described Controt as the engineer who was most representative of the various areas of thought that characterized the profession in the 1930s.[40] According to Jackie Clarke, Coutrot was “a leading light in France’s movement for industrial rationalization: an office-bearer at the Comité national de l'organisation française (CNOF), he addressed numerous meetings and published widely on questions of industrial organization and efficiency.”[41] Controt also took an interest not just in economic matters, but also social, scientific, aesthetic topics. He wrote for publications like Plans, La nouvelle revue francaise, and La grande revue, and to newspapers such as La Republique or Georges Valois’ Chantier cooperatifs.

Center for the Study of Human Problems (CSHP)

Alexis Carrel (1873-1944), member of the Rockefeller-funded CSHP by Aldous Huxley and synarchist Jean Coutrot.

Maria Montessori (1870 – 1952) founder of the Montessori Schools

In 1930s France, many key words transcended the usual right-left divide. In addition to “Revolution,” “Plan,” and “corporatism,” was the term “new man.”[42] The purpose of the CSHP was to create an environment that would foster the evolution of the new man. To this end, Coutrot endorsed the work of Maria Montessori, the founder of the Montessori Method of education. Montessori herself aspired to the creation of a “better type of man, a man endowed with superior characteristics as if belonging to a new race: the superhuman of which Nietzsche caught glimpses.”[43] CSHP members included Hyacinthe Dubreuil, Jean Ullmo, Alfred Sauvy, Henri Focillon, Serge Chakotin participated in CSHP meetings.[44] The CSHP also included Alfred Sauvy, the French demographer who coined the term Third World (“Tiers Monde”). French historian Henri Foucillon, who had been a member of CSHP, became the honorary president of the École Libre des Hautes Études.[45] Professor Roger du Teil of Nice, who was a fellow member of the CSHP, lent his support to the experiments of Freudian psychologist Wilhelm Reich.[46]

The eugenicist Alexis Carrel (1873 – 1944) was also a member of Coutrot’s CSHP.[47] In 1906, Carrel joined the newly formed Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research in New York where he spent the rest of his career.[48] He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912. In 1924 and 1927, as an honorary member of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. From the early 1930s, Carrel advocated the use of gas chambers to rid humanity of its “inferior stock,” and endorsed scientific racism. In 1935, Carrel published a best-seller, L’Homme, cet inconnu (“Man, The Unknown”), which Carrell advocated, in part, that mankind could better itself by following the guidance of an elite group of intellectuals, and by incorporating eugenics into the social framework. In the 1936 preface to the German edition of the book, Carrel had added praise for the eugenics of the Nazis, writing that:

In Germany, the government has taken strong measures against the increase of minorities, lunatics, criminals. The ideal situation would be that every individual of this kind is eliminated when he has shown himself dangerous.[49]

Alexis Carrel became affiliated with the Parti Populaire Français (PPF) of Jacques Doriot (1898 – 1945). In 1941, through connections to the cabinet of Philippe Pétain, Carrel went on to advocate for the creation of the Fondation Française pour l’Etude des Problèmes Humains (French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems), which implemented the eugenics policies under the Vichy regime.[50] Carrel’s association with the CSHP and with PPF led to investigations of collaborating with the Nazis, but he died before any trial could be held.[51]

Rape of the Masses

Sergei Chakhotin (1883 – 1973)

Ivan Pavlov (1849 – 1936)

According to Yann Moncomble, it is worth noting that Carrel’s ideas coincided with the ambitions H.G. Wells and Sergei Chakhotin (1883 – 1973), who worked for Carrel’s institute.[52] Chakhotin was a Russian émigré biologist who worked with physiologist Ivan Pavlov.[53] Chakhotin had numerous contacts with the Fabian Society, including Bertrand Russell, his “great friend” H.G. Wells, and he was also friends with Albert Einstein.[54] Chakhotin, who once referred to himself as “the first minister of propaganda in Europe,”[55] had extensive experience as head of propaganda under Kerensky and later with the anti-Soviet Don government, and during the 1930s as a specialist adviser on anti-Nazi propaganda in social democratic movements in Germany, Denmark, Belgium, Britain and France. Chakhotin designed the Three Arrows, the symbol of the Iron Front, an anti-Nazi, anti-monarchist and anti-communist paramilitary organization formed in the Weimar Republic.[56]

Ludolf von Krehl (1861 – 1937)

Between 1930 and 1933, Chakhotin held a three-year research scholarship at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg. The institute was the vision of Ludolf von Krehl (1861 – 1937), a renowned physician and director of the University of Heidelberg’s Medical Clinic. Von Krehl was a member of the Nationalsozialistischer Lehrerbund (“National Socialist Teachers League”), which was founded by former schoolteacher Hans Schemm (1929 – 1935), the Gauleiter or party leader of the regional branch of Bayreuth, a position obtained only by direct appointment from Adolf Hitler. Its goal was to make the Nazi worldview and foundation of all education and especially of schooling. In 1936, Hitler awarded von Krehl the eagle shield of the German Reich.[57]

With the advent of the Third Reich in 1933, the University of Heidelberg supported became known as a Nazi university, and dismissed a large number of staff and students for political and racial reasons. In 1933, members of the faculty and students took part in book burnings at Universitätsplatz (“University Square.” Most Jewish and Communist professors that did not leave Germany were deported. The inscription above the main entrance of the New University was changed from “The Living Spirit” to “The German Spirit.”[58]

Ludolf-Krehl-Klinik at the University of Heidelberg

The University of Heidelberg was involved in Nazi eugenics, including forced sterilizations carried out at the women’s clinic and the psychiatric clinic, then directed by Carl Schneider (1891 – 1946). Schneider, joined the Nazi Party in 1932, and after the Nazis assumed power in 1933, associates observed his transformation from “a modest scholar with an umbrella and briefcase, occupied with the most subtle kind of investigation of schizophrenia,” to a man who, as “a leader of German psychiatry, took on the mission of preaching National Socialism and offering his own enlightened program of work therapy as a National-Socialist approach par excellence.”[59] Schneider coined the term “national therapy” for ridding the populace of genetic contaminants threatening the psychological and physical health of the Aryan population.[60] He collected the brains of murdered Jews.[61]

Coming under increasing suspicion for this anti-fascist activism, Chakhotin fled to Denmark in 1933, where he was received by his friend Charlotte Weigert a follower of the Anthroposophy of Rudolph Steiner. Weigert introduced Chakhotin to Xenia Jacobsen, widow of the owner of the Carlsberg brewery, and lived at their property which was named “Swastika.” Chakhotin also found work at the Institute of General Pathology of the University of Copenhagen, led by Professor Oluf Thomsen, another great friend of Weigert. There he met atomic physicist, Professor Niels Bohr.[62]

Between 1936 and 1939, Chakhotin became closely associated with Jean Coutrot. Chakhotin found a sympathetic audience in the CSHP for his ideas on conditioned reflexes and propaganda, and was encouraged by them to write the The Rape of the Masses: the psychology of totalitarian political propaganda during 1938.[63] The book, which attempts to synthesize Marxism and behaviorism, was dedicated to Pavlov and H.G. Wells, and soon gained status as a classic work on the theory of propaganda. Although Chakhotin criticized the techniques of persuasion of the Nazis, he nevertheless excused that: “To rapidly build socialism, the true democracy, one must employ the same [fascist] method of provoked obsession, which functions here no longer by fear, but by enthusiasm, joy, and love. A violent propaganda of nonviolence!”[64]

Chakhotin took the work of Pavlov on conditioned reflexes in a new direction, claiming to have discovered that all life forms struggled to survive through four universal instincts, in declining order of potency: the combative or defensive impulse; food; the sex drive, and lastly the protective parental or maternal instinct.[65] Chakhotin claimed to have confirmed in his study of German elections that modern propaganda techniques had more powerful impact on the less educated masses, representing about 90% of the population, than by rational or intellectual arguments that reached only 10%. The 10%, according to Chakhotin, “is composed of the politically indifferent and hesitant, also the lazy, tired and exhausted, depressed by the problems of everyday life… beings who have a fragile nervous system, who allow themselves to be easily manipulated by imperative orders, who are readily seized by fear, and who often are quite happy to be dominated and directed”.[66] Thus, by targeting the majority through propaganda based on aggression and fear, it was the Nazi Party that was proving most successful, with an increasing possibility of seizing power through a constitutional or “democratic” coup. The key to gaining influence over the masses, Chakhotin argued, was through repetitive use of symbols that could act instantaneously on emotions and trigger conditioned reflexes.[67]

Open Conspiracy

H.G. Wells, mentor to Aldous Huxley and author of The Open Conspiracy

Chakhotin dedicated The Rape of the Masses to Pavlov and H.G. Wells who praised the work.[68] One of the main ideas of the book was one also dear to Wells: a federal world state, for which Chakhotin provided a diagram of its proposed structure. The book, according to Wells:

… is the most luminous and comprehensive exposition of contemporary social psychology. This book deals with the subject from all sides and thoroughly. He analyzes the historical process in the light of the most modern criticism, and the diagnosis of the events we are experiencing leads him to the convincing establishment of the measures to be taken. I am proud to say how much I agree with the ideas presented in this book as masterful as modern.

Chakhotin diagram of his proposed federal world state: Pm, World Legislative Assembly; Gm, World Government; Cm, World Federal Council; En, National States; rE, representatives of States (present UN); Gf functional groups; f, women; t, workers; i, intellectuals (cultural forces); e, educators; j, youth. c.o.n.i., confederations national intellectual organizations; rf, representatives of functional groups; ec, cultural elites; re, representatives of cultural elites (the great men); c, confederation; f, federations; A-P, federated associations.

One of the main ideas of Chakhotin’s book was one dear to Wells as well: a federal world state, for which Chakhotin provided a diagram for its proposed structure. In 1944, Chakhotin founded Science Action Liberation (SAL), to fulfill the “Plan,” which coincided exactly with the ideas of Wells’ Open Conspiracy.[69] The five founders of were Pierre Girard, G.E. Monod-Herzen, Francois Perroux, Morris B. Sanders and Chakhotin. Monod-Herzen was a member of the Theosophical Society, as well as the Brotherhood Polaires, and author of works on alchemy and Sri Aurobindo[70] Perroux, a French economist, was a student of Joseph Schumpeter and a friend of Carl Schmitt, was Secretary-General of Carrel’s French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems.[71] In 1934, Perroux was awarded a Rockefeller Fellowship which allowed him to travel to Vienna, where he met Ludwig von Mises, whose seminars he followed and whose preface to the French edition he wrote in 1935.

The seat of this new organization was fixed at the Institute physics and chemistry Pierre Girard. Girard was very close to Baron Edmond de Rothschild who donated 40 million francs to build his Institute of Biology. The Institute’s founders included Professor Charles Richet, physiologist, member of the Cosmos Lodge, of the Grand Lodge of France, former president of the French Peace Council, and board member of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.[72] Girard also obtained a grant of 60,000 francs from Guy de Rothschild, as well as a donation of from SAL member Louis Sachs, the Rothschild Foundation and the Masonic Lodge Unity.[73]

Nicholas Murray Butler (1862 – 1947) president of Columbia University, and president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Another member of SAL was Gnostic Bishop, André Sébastien, who was also a member of the Supreme Martinist Council.[74] The Grand Master was Constant Chevillion (1880 – 1944), an official with the Banque Nationale du Commerce et de l’Industrie, as well head of FUDOSI, and Grand Master of the Martinist Order and Memphis-Misraïsm, and also Patriarch of the Gnostic Church. When a copy of Synarchist Pact was discovered in his home, he eventually admitted that it had been sent to him by Jeanne Canudo so he could “compare its tenor to the synarchic principles of Saint-Yves d’Alveydre.”[75] Michel Gaudart de Soulanges and Hubert Lamant in their Dictionary of French Freemasons identify Chevillon as a member of the MSE.[76]

Morris B. Sanders had been involved in the OSS, was also a board member of the Carnegie Endowment.[77] Sanders, who was a founding member of SAL, introduced Chakhotin to Malcolm Davis, the European director of Carnegie Endowment, and Waldemar Kaempffert, science writer at the New York Times, a member of the American Society for Psychical Research and a friend of the parapsychologists James H. Hyslop and Walter Franklin Prince.[78]

United World Federalists

Contacts also included Clyde Miller, founder of the Institute for Propaganda Analysis and Associate Professor at the University of Columbia, and his friend Nicholas Murray Butler (1862 – 1947), Director of Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CFIT), President of the Pilgrims Society, and a recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. According to Professor Robert McCaughey, historian and author of Stand, Columbia, Butler “had a personal stake in seeing Columbia—and himself—as an international figure.”[79] This led to the university seeking ties with rising fascist leaders. In 1933, Butler hosted a warm welcome for Hans Luther, Nazi German ambassador who was appointed as Hjalmar Schacht’s successor as president of the Reichsbank in 1930.[80] Luther’s speech stressed Hitler's “peaceful intentions” toward his European neighbors. As Stephen H. Norwood writes in The Third Reich in the Ivory Tower: Complicity and Conflict on American Campuses, “American universities maintained amicable relations with the Third Reich, sending their students to study at Nazified universities while welcoming Nazi exchange students to their own campuses.” In so doing, he concludes, “they helped Nazi Germany present itself to the American public as a civilized nation, unfairly maligned in the press.”[81] Columbia students staged a mock book burning in 1936 to protest Butler’s decision to send a delegate to the University of Heidelberg’s 550th anniversary celebration.

Columbia students stage a mock book burning in 1936 to protest Nicholas Murray Butler’s decision to send a delegate to the University of Heidelberg’s 550th anniversary celebration. (Columbia University Archives)

Sanders also in contact with the United World Federalists, whose administrators included Albert Einstein, Cord Meyer, Jr., Edward M.M. Warburg, Norman Cousins, Cass Canfield, Chair from Harper & Bros of New York, and Grenville Clark (all three of the CFR), W.T. Holding, President of the Standard Oil, and Lehman partner Arthur H. Bunker Brothers and Charles D. Hilles, Jr., vice president of ITT. The United World Federalists asked Chakhotin to communicate to them “if possible, the names of students and professors of universities and secondary schools, as well as the names and addresses of political groups of students who might be interested in working towards the establishment of a World Government.”[82]

Front populaire

Demonstration of the Popular Front Place de la Nation, July 14, 1936. (Leon Blum in the center).

Jacques Doriot (1898 – 1945)

The ascent of Front populaire (“Popular Front”) dealt a serious blow to the banks Banque Worms, the Rothschilds, Lazard and other industrialists.[83] The Popular Front was an alliance of left-wing movements and the socialist French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) during the interwar period. The Popular Front won the 1936 elections, leading to the formation of a government first headed by SFIO leader Leon Blum and exclusively composed of republican and SFIO ministers. Blum’s government implemented various social reforms. The workers’ movement, which welcomed electoral victory, launched a general strike, resulting in the negotiation of the Matignon agreements, one of the cornerstones of social rights in France. All employees were assured a two-week paid vacation, and the rights of unions were strengthened. The Popular Front dissolved itself in autumn 1938, confronted by internal dissensions, opposition from right-wing movements, and the lingering effects of the Great Depression.

The bankers, therefore, decided to create an extreme right-wing party, financed by capitalists, the French People’s Party. The president of Banque Worms, Gabriel Leroy-Ladurie, made contact with former French Communist Party (PCF) member Jacques Doriot in 1936, to found the Parti Populaire Français (PPF), an anti-Semitic and anti-Bolshevik party that advocated “national revolution.”[84] The PPF vehemently opposed both Marxism and liberalism, and also wished to rid France of Freemasonry. The PPF received financial support from the synarchist Banque Worms.[85] The Rothschild and Lazard banks had also previously been among the original donors of PPF.[86]

PPF propaganda poster

Doriot’s PPF attracted former members of Action Française, Jeunesses Patriotes, Croix-de-Feu and Solidarité Française.[87] The Croix-de-Feu was financed by top industrialists and bankers like André Michelin (tires), Louis Renault (cars) and François Coty (perfume and newspapers). The Wandel (munitions) and Rothschild (banking) families were also its sponsors.[88] Many conservative Catholics became members of the Croix-de-Feu following the Catholic Church’s 1926 prohibition of supporting the Action Française, including the young François Mitterrand.[89]

Following the victory of the Popular Front in 1936, Coutrot was invited to head the Centre national de l’organization scientifique du travail (COST), which was created by an official decree signed by Leon Blum and Charles Spinasse, who became Minister of National Economy. According to the Chavin Report, Coutrot became an intimate adviser to Spinasse, and then took the opportunity to introduce the greatest number possible of members of the MSE into the government. He also worked to sabotage Spinasse’s efforts for economic and social reform, while providing recommendations that was unrealizable.[90]

Coutrot was also in contact with the SSS, originally the National Socialist Workers’ Party (Sweden), formed in 1933 by Sven Olov Lindholm, to serve as a acted as a simple mirror of the German Nazi Party.[91] In 1938, parts of the Swedish Nazi movement broke with Hitler, and the NSAP changed its name to the Swedish Socialist Coalition (SSS) and replaced its swastika with a bundle of wheat (Vasakärven), an old Swedish emblem used by King Gustavus II Adolphus, the so-called “The Lion of the North.”

Sohlberg Circle

Otto Abetz (1903 – 1958), SS member, German ambassador to France and close friend of Joachim von Ribbentrop

Denis de Rougemont, Alexandre Marc the Protestant theologian Karl Barth en 1934.

Spinasse had been a member of Ordre Nouveau (“New Order”), to which also contributed Coutrot and Denis de Rougemont. A central part of the non-conformist movement, Ordre Nouveau was founded in 1933 by Alexandre Marc (1904 – 2000) who with de Rougemont belonged to the Sohlberg Circle (Sohlbergkreis), which played an important role in building the circle of collaborators in France. Sohlberg was founded in 1931, youth at the Black Forest town of Sohlberg, by Otto Abetz (1903 – 1958), a member of the SS, who was in charge of the Nazy Party’s relations with French intellectual circles before becoming ambassador of the Reich.[92] As a member of the Hitler Youth, Abetz became a close friend of Joachim von Ribbentrop.[93] He was also associated with groups such as the Black Front, a political group formed by Otto Strasser after he resigned from the Nazi Party to avoid being expelled in 1930.[94] Abetz pledged his support for the Nazi party in 1931. In Paris, Abetz joined Masonic lodge Goethe in 1939.[95] In 1940, following the German occupation of France, he was assigned by von Ribbentrop to the embassy in Paris, as the official representative of the German Government with the honorary rank of SS-Standartenführer.[96]

Alexandre Marc, disciple of Husserl and Heidegger, was born in 1904 as Alexandr Markovitch Lipiansky in Odessa, Russian Empire, to a Jewish family, but later converted to Catholic Christianity. As shown by Martin Mauthner, author of Otto Abetz and His Paris Acolytes, many of Abetz’s chief protegees in Paris had Jewish family ties. Jules Romains, (1885 – 1972), a French poet and writer and the founder of the Unanimism literary movement, who was accommodated by the German government at the Hotel Adlon when he gave a talk in Berlin in 1934, had a Jewish wife. Fernand de Brinon (1885 –1947), the first French journalist to interview Hitler, was married to Lisette, a Jewish woman converted to Catholicism. He became friends with von Ribbentrop. Another journalist, Jean Luchaire (1901 – 1946), had an actively anti-Nazi Jewish stepmother, Antonina Vallentin, born Silberstein. The political thinker, Bertrand de Jouvenel (1903 – 1987), who wrote flattering interview with Hitler in 1936, had a Jewish mother. That same year he joined Doriot’s PPF.[97]

Also married to a Jewish woman and working with Abetz was the French writer Pierre Drieu la Rochelle (1893 – 1945), an admirer of England and also a friend of Aldous Huxley. Drieu hoped for a uniquely French form of fascism that would contribute to an international fascist order. Drieu was editor of the collaborationist journal Novelle Revue Française, founded in 1909 by André Gide. In 1911, Gaston Gallimard became editor of the revue, which led to the founding of the famous publishing house, Éditions Gallimard. In the 1920s, Drieu was sympathetic to Dada and to the Surrealists and the Communists, and a close friend of Louis Aragon (1897 – 1982), who co-founded the surrealist review Littérature with André Breton and Philippe Soupault. Drieu was also interested in the royalist Action Française. Drieu became a proponent of French fascism in the 1930s, and joined Doriot’s PPF in 1936, and became the editor of its review, L’Emancipation Nationale.[98]

Jacques Maritain (1882 – 1973) and his wife Raïssa Oumançoff

Emmanuel Mounier (1905 – 1950)

By 1934, Abetz was picked by Ribbentrop to be the Nazi party’s advisor on France. Abetz showed particular interest in groups of religious inspiration centered on publications such as Ordre nouveau, Esprit and Plans, even though they were opposed to Hitlerism, fascism, Bolshevism and American capitalist fascism.[99] These organizations and publications belonged to the what the French historian Jean-Louis Loubet del Bayle labelled “the non-conformists of the 1930s” in his 1969 classic, who revolved around personalism, a doctrine associated above all with Mounier and his Social Catholic collaborators on the review Esprit.[100] Coutrot was also familiar with the writings of Jacques Maritain, who would become an important figure in the early history of Personalism. Maritain, a close friend of Charles Maurras, and who had been involved in Action francaise, where he befriended Jean Cocteau. Maritain was also a founding member of the French branch of the Frankfurt School, the École Libre des Hautes Études, established with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation.[101] In a meeting between the two, Controt asked Maritain to contribute an article to the CSHP bulletin.[102]

The non-conformist movement, which sought new solutions to perceived political, economic and social crisis of the 1930s, were at the heart of the intellectual ferment that marked the inter-war period in France.[103] The Non-Conformists were influenced both by French socialism, in particular by Proudhon and by Social Catholicism. Foreign influences included the existentialism of Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger and Max Scheler, as well as contacts with several members of the German Conservative Revolutionary movement.[104] The non-conformists called for a “New Order,” and attempted to find a “third (communitarian) alternative” between socialism and capitalism, and opposed both liberalism, parliamentarism, democracy and fascism.[105]

In 1932, Marc participated in the founding of the journal Esprit, a nominally a Catholic review founded by Emmanuel Mounier, a protégée of Jacques Maritain, which published the work of Pierre Klossowski and de Rougemont.[106] Maritain and Mounier were part of the Catholic renaissance which took place in France in the early twentieth century. They were a generation of young French intellectuals who drew inspiration from Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical De Rerum Novarum (1891), which in 1891 marked the beginning of the development of social teaching in the Catholic Church. They sought to develop a rational Catholic response to the challenges of industrialism, materialism, and collectivism.[107] Mounier was distrustful of those elements of the modern era such as “individualism” and “liberalism,” and was convinced that the Catholic faith could offer an alternative to the age of materialism.[108] However, Jewish anti-fascist Zeev Sternhell claimed that the “revolt against individualism and materialism” of Mounier’s personalism movement shared the ideology of fascism.[109] Maritain provided financial backing, office space and a range of contributors to Esprit, and introduced Mounier to intellectuals like Berdyaev.[110] According to the French personalist historian and theologian Olivier Clément, Berdyaev had shaped Mounier’s philosophy of personalism, an intellectual position that emphasizes the importance of the person.

Robert Aron (1898 – 1975)

Ordre Nouveau was based on reviving a “New Middle Ages,” following the Russian mystic and fascist, Nikolai Berdyaev, who had advanced the concept of the Third Rome in Russia, equating it with the Third International. Having settled in the area of Paris in 1924, with the support of Stanislas Fumet and his wife, Berdyaev rapidly entered the circle meeting at Jacques Maritain’s home in Meudon, where he became relatively influential.[111]

The Ordre Nouveau journal was founded by French-Jewish historian Robert Aron and Arnaud Dandieu. Their work together included Décadence de la Nation Française (1931), Le Cancer Américain (1931) and La Révolution Nécessaire (1933), which constituted the principal theoretical base Ordre Nouveau, which with Esprit represented one of the most original expressions of the Nonconformist Movement. Dandieu was a friend of de Rougemont and Georges Bataille, who were colleagues at the Bibliothèque Nationale.[112] Bataille assisted in the writing of Dandieu and Aron’s La Révolution Nécessaire. Dandieu and Aron were editors of the French journal Documents, where Bataille was General Secretary.[113] In their infamous 1933 “Letter to Hitler,” the Ordre Nouveau welcomed the way the Nazis had overturned the liberal political order and capitalism, but denounced their idolization of the state and racism.[114] Charles de Gaulle was also associated with Ordre Nouveau between the end of 1934 and the beginning of 1935.[115]

Révolution nationale

Mounier’s thought had a direct and formative influence on a key institution of Philippe Pétain’s National Revolution: the Ecole des Cadres at Uriage, near Grenoble.[116] The École des cadres d’Uriage was created by Cavalry Captain Pierre Dunoyer de Segonzac, immediately after the 1940 defeat with the support of the Vichy regime’s Secretariat for Youth. Resisting the multiple pressures exerted by the regime, de Segonzac’s school exercised a great deal of autonomy, enabling it to turn it into a breeding ground for the Resistance. Nevertheless, Pétain had great confidence in de Segonzac, who received the Francisque.[117]

The National Revolution, Révolution nationale in French, the official ideological program promoted by the Vichy regime, was an adaptation of the ideas of the French far-right, including monarchism and Charles Maurras’ integralism, by a crisis government, born from the defeat of France against Nazi Germany in 1940. Inspired by Maurras’ concept of the “Anti-France,” or “internal foreigners,” as soon as it was established, the Vichy government took measures against the four groups of “undesirables,” namely Jews, immigrants, Freemasons and Communists. Those who supported the National Revolution without supporting Pétain himself could be divided into three groups: counter-revolutionary reactionaries, supporters of a French fascism and reformers. The Reactionaries were part of the counter-revolutionary branch of the French far right, the oldest one being composed of Legitimists, monarchist members of the Action française, and so on.

The French fascists attacked Vichy and Maurras for not seeking to bring National Socialism to France.[118] They included, among others, the supporters Jacques Doriot’s PPF, and members of the Cagoule, a synarchist terrorist group funded by L’Oreal founder Eugène Schueller (1881 – 1957). In 1938, the PPF of Doriot thus called for unity with the Reich, against the USSR. When France went to war with Germany in 1939, Doriot became a staunch pro-German and supported Germany’s occupation of northern France in 1940. In 1941, he and fellow fascist collaborator Marcel Déat founded the Légion des Volontaires Français (LVF), a French unit of the Wehrmacht.

The reformers included the non-conformists, Christian-democrat personalists and Groupe X-Crise. All of these circles would also provide recruits to the Resistance.[119] The École des cadres d'Uriage would form the basis after the War of the elite school École nationale d'administration (ENA), a French grande école, created in 1945 by French President, Charles de Gaulle, and principal author of the French Constitution, Michel Debré, to democratize access to the senior civil service. After the war, the writer and World War I hero Henri de Kérillis accused de Gaulle of having been a member of La Cagoule, asserting that de Gaulle was ready to install a fascist government if the Allies allowed him become France’s chief of state.[120]

La cagoule

Parisian Members Of The Cagoule (A Secret Committee For Revolutionary Action) Drinking In Honor Of Their Succesful Conspiracy, Unconcerned About Police Pursuits, On December 3, 1937

L’Oreal founder Eugène Schueller (1881 – 1957)

CSAR (Secret Committee for Revolutionary Action), also known as La Cagoule, was founded by Eugene Deloncle (1890 – 1944), who was briefly associated with Jacques Doriot and the PPF, as a breakaway group of the Action Français, and which maintained close links with Coutrot’s MSE.[121] On January 9, 1934, Serge Alexandre Stavisky (1885 – 1934), a Jewish con man close to the French anti-religious Freemasonry, was found dead. Rumors quickly spread that Stavisky did not commit suicide, but had been murdered by the police in order to prevent him from revealing his dealings with the Chautemps government. Protestors took to the streets of Paris, and Chautemps was forced to resign on January 30. However, the Action Française called for a mass rally on February 6. Republican authorities feared that a Monarchist coup was being prepared. When the crowd refused to disperse, policemen fired, leaving four Action Française activists dead and many injured.[122] The tragedy then caused a split in the Action Française. While Maurras refused to call for a general Monarchist insurrection against the Republic, one of the movement’s leaders, Deloncle, created a splinter group known as CSAR, which decided to go underground and to organize terrorist activities.

CSAR, also known as La Cagoule, was a violent fascist, anti-Semitic, and anti-communist group, with initiation rites resembling those of the Freemasons, that used violence to promote its activities to overthrow the French Third Republic, led by the Popular Front government, and was bankrolled by Eugène Schueller. The term cagoule had been applied first by Charles Maurras and Maurice Pujo of Action francaise to Deloncle and his followers, who had turned against what they had perceived as inaction by the older organization in combatting the French Left. Their tactics reminded Maurras of the American Ku Klux Klan, hence the appellation cagoule, or “hood.”[123] The Chicago Tribune’s correspondent in Paris, William Shirer, summed up the Cagoule as “deliberately terrorist, resorting to murder and dynamiting, and its aim was to overthrow the Republic and set up an authoritarian régime on the model of the Fascist state of Mussolini.”[124]

Eugène Deloncle even likened its recruiting procedures to the “chain method” of the Illuminati.[125] According to Richard Kuisel, a specialist in twentieth-century French political history: “Strangely enough, although the Cagoule was an archenemy of Freemasonry, it imitated Masonic ritual, symbolism, and method of recruitment. The head of the Cagoule, Eugène Deloncle, even likened its recruiting procedures to the ‘chain method’ of the Illuminati.”[126] In Nice, in the presence of the Grand Master adorned in red and accompanied by his assesseurs dressed in black, new members of the Cagoulards were submitted to an initiation ritual in which their faces were covered, and standing before a table draped with a French flag on which a sword and torches would be deposited, they raised their right arm and swore the oath Ad majorem Galliæ gloriam (“for the greater glory of France”), echoing the Jesuit motto Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam (for the greater glory of God).[127]

In 1939, following the Spanish Civil War and a revival of anti-communism in the Catholic Church, Pope Pius XII decided to end the condemnation of Action française. During the war, Action française supported the Vichy Regime and Pétain. During the war, Deloncle served as an advisor to Max Thomas, who headed the Gestapo and SS Security Service (SD) forces in France in 1941, and worked with Hans Sommer, as an SS-Obersturmführer, who was seeking separatist Breton, Basque and Corsican groups.[128] Deloncle was assassinated in 1944 by the Gestapo, through the SD’s French agents, because of his relations with Admiral Canaris and other members of the Abwehr opposed to Hitler.[129]

Mouvement Social Révolutionnaire (MSR)

Eugène Deloncle (center, 1890 – 1944)

During World War II, members of the Cagoule were divided. Some of them joined various Fascist movements. Schueller and Deloncle founded the Mouvement Social Révolutionnaire (MSR), which supported the idea of the Nazis’ New Order in Europe in the belief that France could become a great power again alongside the Third Reich.[130] MSR was described in a German report as the first successful synthesis in France of socialism and nationalism, incorporating the best French revolutionaries.[131] Unlike the Cagoule, the MSR supported close collaboration with Germany.[132] Colonel Serge Groussard, who collaborated with the Cagoule, indicated that Deloncle had contacted General von Stilpnagel, the German Army Chief in Paris, and that from the outset the party was financed at least in part by the Propagandastaffel (“propaganda squadron”), a German service in charge of propaganda and control of the French press and of publishing during the occupation of France.[133]

The prosecution at Harispe’s trial in 1948 asserted that according to Rudolf Schleier, Deputy to Otto Abetz, Deloncle was receiving 300,000 francs per month from the German Embassy.[134] According to Charles Higham, author of Trading With The Enemy, Abetz and the German Embassy poured millions of francs into various French companies that were collaborating with the Nazis. On August 13, 1942, 5.5 million francs were passed through in one day to help finance the military government and the Gestapo High Command. This money helped to pay for radio propaganda and a campaign of terror against the French people, including beatings, torture, and brutal murder. Abetz paid 250,000 francs a month to fascist editors and publishers in order to run their vicious anti-Semitic newspapers. He financed the MSR, which flushed out anti-Nazi cells in Paris and saw to it they were liquidated. In addition, Abetz used embassy funds to trade in Jewish art treasures, including tapestries, paintings, and ornaments, for the benefit of Hermann Göring, who wanted to get his hands on every French artifact possible.[135]

In 1941, Deloncle contacted the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the intelligence agency of the SS, in an attempt to enlist their help in gaining a high governmental post at Vichy. As he was known to have expressed anti-German sentiments before the war, Deloncle was asked to prove the sincerity of his desire for collaboration. Deloncle therefore approached SS Obersturmfuhrer Hans Sommer with a proposal to attack Jewish synagogues in Paris, which were carried out during the night of October 2-3, 1941. Introduced to Deloncle by Sommer, Helmut Knochen, the senior commander of the SD in Paris, approved the attack. It also received the support of Heydrich, who had told Knochen in advance that it would not be necessary to inform the Military Command.[136]

Vichy Government

François Darlan (1881 – 1942)

During the trial of Marshall Pétain in 1945, questions were asked about his connection with the Synarchist Pact.[137] l'Appel, which recorded the announcement of Coutrot’s mysterious death in 1941, revealed that most of the ministers and generals in the Vichy regime belonged to the MSE.[138] Also closely associated was Admiral François Darlan (1881 – 1942), a major figure of the Vichy regime in France during World War II, who became its deputy leader for a time. Accusations arose that synarchists had engineered the military defeat of France for the profit of Banque Worms, a division of Worms & Cie.[139] According to former OSS officer William Langer, as reported in Our Vichy Gamble:

Darlan’s henchmen were not confined to the fleet. His policy of collaboration with Germany could count on more than enough eager supporters among French industrial and banking interests—in short, among those who even before the war, had turned to Nazi Germany and had looked to Hitler as the savior of Europe from Communism… These people were as good fascists as any in Europe. Many of them had extensive and intimate business relations with German interests and were still dreaming of a new system of ‘Synarchy,’ which meant government of Europe on fascist principles by an international brotherhood of financiers and industrialists.[140]

The Chavin Report accuses the MSE of laying the groundwork for the eventual seizure of power by the Cagoule, who by blackmail helped accelerate the military defeat of 1940 that put Petain in power. Under Petain, the MSE controlled the entire Ministry of the National Economy and Finance. Their goal was to defeat any attempt at an exclusively European-inspired economic and customs integration that would make continental Europe independent of American imports. The aim was to design financial agreements between the French and German people in order to unite the oil, textile, mining and other big industries, in such a way that their interests lead them to put fair pressure on their government so that the Judeo-American interests were fully protected. The command was given to seek a series of agreements with German firms like IG Farben and Dupont, to create solidarity with German industry leaders, all strongly structured and designed with the aim of joining the American groups at the end of the war. The negotiations were held in the occupied zone in Lyon, Basel, with the leaders of IG Farben and an attaché from the American Embassy in Vichy, which at the time was headed by Admiral William Daniel Leahy, close friend President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[141]

According to Charles Higham, author of Trading with the Enemy, Banque Worms was an important component of The Fraternity involved in financing the Nazis, through connections that linked the Paris branch of Chase to Schröder and Standard Oil of New Jersey in France. On May 23, 1940, two weeks after the Nazis occupied France, as reported by Paul Manning, in his detailing of Bormann’s Aktion Adlerflug (“Operation Eagle Flight”), all French banks were brought under the supervision of the German banking administration. In the years prior to the war the German industrialists and bankers had established close ties with their counterparts in France. Following the occupation, they agreed to the establishment of German subsidiary firms in France and permitted the acquisition of equity stakes in French companies. In Paris the usual direct penetration took place by shareowner control of such as the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, Banque Nationale pour le Commerce et l’Industrie (now Banque Nationale de Paris), and Banque de l’Indo Chine (now Banque de l’Indo Chine et de Suez Group), and most importantly, Worms et Cie. (now Banque Worms Group). [142] Standard Oil’s Paris representatives were directors of the Banque de Paris et des Pays-Bas, which had intricate connections to the Nazis and to Chase.[143]

After the fall of Paris, Banque Worms “Aryanized” its entire board of Jewish executives. The head of the German subsidiary of Worms et Cie was Alexander Kreuter (1886 –1977), an influential German business lawyer and banker during the Nazi occupation of France. Kreuter was a member of the General SS, working in the Nazi foreign intelligence service headed by Walter Schellenberg.[144] Kreuter was connected to Dillon, Read, the Jewish banking firm that had helped finance Hitler until 1934 and with whom Allen Dulles was involved. According to Charles Higham, “Kreuter’s activities with the Americans are obscure, he belonged to a joint American-French- British business group in Vichy and ran so close to the wind with Hitler that he was arrested on suspicion of espionage for America, and only Schellenberg’s personal guarantee of his bona fides secured his release.”[145]

During his time in Vichy, Darlan brought a whole clique of Banque Worms into the government. After the outbreak of World War II, Hypolite Worms was placed in charge of the French delegation to the Franco-English Maritime Transport Executive in London. After the Fall of France in June 1940 he took responsibility for transferring the French merchant fleet to Britain, and on July 4, 1940, signed what was called the “accords Worms.” He then returned to France through Portugal and Spain, and reported to Darlan in Vichy. The French ordinance of October 18, 1940, placed companies whose leaders were not considered true Aryans under state control. Although Hypolite was born of a Christian mother and had been baptized at birth, Worms & Cie was placed under state supervision, and Hypolite became the target of violent attacks in the pro-German press.[146]

The key leaders of the MSE involved in the regime included Paul Baudoin, Jacques Gudrard, Jacques Barnaud, and Jacques Benoit-Mechin. Another MSE member included Paul Reynaud, who after the outbreak of World War II had become the penultimate Prime Minister of the Third Republic in March 1940. In the last months before France’s capitulation, Paul Baudoin, a major member of Opus Dei, a director of the Banque d’Indo-Chine and a friend of Mussolini, became right-hand adviser to Reynaud, with the help of Reynaud’s lover Hélène de Portes. Jacques Gudrard was a banker who held the post of Ambassador to Lisbon under the Vichy regime. An important Cagoule member was Joseph Darnand (1897 – 1945), who later founded the Service d’ordre légionnaire (SOL), the forerunner of the Milice, the Collaborationist paramilitary of the Vichy regime, who fought the French Resistance and enforced anti-semitic policies. Darnand took an oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler after accepting a Waffen SS rank.[147]

One of the three managing directors of Banque Worms, MSE member Jacques Barnaud (1893 – 1962), a favorite with Göring, was responsible for handing over to the Germans the major French chemical industries headed by the Francolor trust. Following the appointment of Darlan as Prime Minister of France in 1941, Barnaud was appointed official delegate general for Franco-German economic relations until December 1942.[148] A favorite with Göring, Barnaud was enthusiastic about the Vichy regime and used his position to work with the Nazis in order to secure deals to supply them with aluminum and rubber from French Indo-China.[149] William D. Leahy, the United States ambassador to France reported to his friend Franklin D. Roosevelt that French industrialist Lehideux was part of a group of strongly pro-Nazi figures that Pétain had surrounded himself with.[150]

Along with the likes of fellow MSE members Jean Bichelonne, François Lehideux and Pierre Pucheu, Barnaud was a member of a group of technocrats who were important in the early days of the Vichy regime.[151] These individuals, sometimes known as jeunes cyclistes (“young cyclists”), advocated extensive economic reform in order that France could become a leading player in the German-led Europe that they saw emerging.[152] Benoist-Méchin (1901 – 1983) was a French journalist and historian who served as an undersecretary in Darlan’s cabinet and, along with Pierre Pucheu and Paul Marion, became part of jeunes cycliste.[153] Benoist-Méchin was also a friend of James Joyce and attempted to translate Ulysses. He also developed a close friendship with Oswald Mosley who lived in France after the war.[154] Benoit-Mechin, who was the author of a book on the Reichswehr, was rewarded for his services to the German army by being named a director of the Banque Worms after the 1940 armistice.[155]

Pierre Pucheu (1899 – 1944)

Darlan also brought in Pierre Pucheu (1899 – 1944), director of several companies of the Worms, became Secretary of State for Industrial Production and then for the Interior in Vichy. A former member of the PPF, Pucheu was the conduit for the transmission of Worms group funding and synarchy in general to the PPF. Pucheu was also Vichy Minister of the Interior and organizer of the Franco-German steel cartel. In the summer of 1942, Pucheu had a meeting at the BIS where he told Yves Bréart de Boisanger about plans for Eisenhower to invade North Africa which he learned about through a friend of Robert Murphy, U.S. State Department representative in Vichy. Boisanger contacted Kurt von Schröder who immediately, along with other German bankers and their French correspondents, transferred 9 billion gold francs through the BIS to Algiers. Expecting a German defeat, the collaborationists were hoping to profit from dollar exchange, and boosted their holdings from $350 to $525 million almost. The deal was made with the collusion of Thomas H. McKittrick, Hermann Schmitz, Emil Puhl, and the Japanese directors of the BIS. Another collaborator in the scheme, according to a statement made under oath by Otto Abetz to American officials in 1946, was one of the Vatican’s espionage group who leaked the secret to others in the Hitler High Command.[156]

Collaborators

Jean Cocteau and Arno Breker, Hitler’s favorite artist

Benoist-Méchin, like Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, had been a member of Otto Abetz’s Sohlberg Circle. In 1939, France expelled Abetz as a Nazi agent. However, on the day German troops entered Paris on May 10, 1940, Ribbentrop, now foreign minister, ordered Abetz to go to Paris and ensure his ministry’s visibility there. Reaching Paris twenty hours after German troops had entered the capital, Abetz installed himself in the former German embassy. In November 1940, Abetz was appointed to the German Embassy in Paris. Abetz then manoeuvred three of his French publicist friends, Jean Luchaire, Fernand de Brinon, Drieu la Rochelle, into key positions, from where they could praise Nazi achievements and denounce the Resistance.[158] Drieu sat on the governing committee of the Groupe Collaboration, established in September 1940, whose headquarters were in Paris, although the Groupe was permitted to organise in both Vichy France and the occupied zone. The initiative had the support of Abetz and was at least partially supported financially by the Nazi governement.[159]

During the occupation of Paris, Drieu succeeded Jean Paulhan as director of the Nouvelle Revue Française (NRF) and thus became a leading figure of French cultural collaboration with the Nazi occupiers, who he hoped would become the leader of a “Fascist International.”[160] At the beginning of 1939, Walter Benjamin sent Max Horkheimer of the Frankfurt School a report on the special issue of the Nouvelle Revue Française, during Paulhan’s time as editor, which was devoted to the College of Sociology, and which contained three manifestos: George Bataille’s “Sorceror’s Apprentice,” Roger Caillois’ “Winter Wind,” and Michel Leiris’ “The Sacred in Everyday Life.”[161] The NRF’s publisher, Gaston Gallimard, ceded the management of the NRF to Drieu, in order to please the Nazis. On the one hand, he hosted in its offices the secret meetings of Les Lettres françaises, a publicaiton of the Resistance, founded by Paulhan, while simultaneously publishing translations of German classics, like Goethe and Ernst Jünger to appease the Nazis.[162]

Along with several personalities of the avant-garde, such a Man Ray, André Breton and Georges Bataille, Paulhan was also participant in the sessions of the sexual mystic Maria de Naglowska.[163] Paulhan admired the Marquis de Sade’s work and told his lover, French author Anne Desclos, that a woman could not write like Sade. To challenge him, Desclos wrote for him the Story of O, under the pen name Pauline Réage. Story of O is a tale of sado-masochism, involving a beautiful Parisian fashion photographer named O, who is taught to be constantly available for oral, vaginal, and anal intercourse, offering herself to any male who belongs to the same secret society as her lover. She is regularly stripped, blindfolded, chained, and whipped, while her anus is widened by increasingly large plugs, and her labium is pierced and her buttocks are branded. In 1955, Story of O won the French literature prize Prix des Deux Magots, a major French literary prize, but the French authorities brought obscenity charges against the publisher.

Despite Hitler’s hesitations and against the opposition of Himmler and Goebbels, Abetz was convinced the French could be won over to the idea of collaboration and the acceptance of their own subservience to a German world order. During several meetings with Hitler, Abetz argued that it was in the interest of Germany to implement a strategy of Divide and Rule to reduce France to the status of a “satellite state” with a “permanent weakening” of its position in Europe. Abetz claimed that “the French masses” already admired Hitler and that, with the right propaganda, it would be easy to lead them blame their misfortunes on the various scapegoats: politicians, Freemasons, Jews, the Church and others who were “responsible for the war.” The French elite and intelligentsia could be won by exposing them to German culture and especially by emphasizing “the European idea.” In Abetz’s words: “In exactly the same way as the idea of peace was usurped by National Socialist Germany and served to weaken French morale, without undermining the German fighting spirit, the European idea could be usurped by the Reich without harming the aspiration to continental primacy embedded by National Socialism in the German people.”[164]

Through the ambassador to Bucharest, Paul Morand, Benoist-Méchin met with Ernst Jünger, who was assigned to an administrative position as intelligence officer and mail censor in Paris.[165] According to Eliot Neaman, in his foreword to Jünger’s A German Officer in Occupied Paris, as a well-known author, Jünger was welcomed in the best salons in Paris, where he met with intellectuals and artists across the political spectrum. A number of conservative Parisian intellectuals greeted the Nazi occupation, including the dramatist Sasha Guitry and the writers Robert Brasillach, Marcel Jouhandeau, Henry de Montherlant, Paul Morand, Drieu la Rochelle, Paul Léutaud and Jean Cocteau.[166]

Florence La Caze Gould (1895 – 1983)

Ernst Jünger (1895 – 1998) was, leading figure of the German Conservative Revolution

Jünger frequented the Thursday salon of Paris editor for Harper’s Bazaar, Marie-Louise Bousquet, who was married to the playwright Jacques Bousquet. Pablo Picasso and Aldous Huxley frequented the meetings, as well as Drieu la Rochelle and Henry de Montherlant. Another of Jünger’s key contacts in Paris was the salon of Florence Gould, where he fraternized with Georges Braque, Picasso, Sacha Guitry, Julien Gracq, Paul Léautaud, and Jean Paulhan, one of the founders of the resistance newspaper Lettres Françaises, and his friend Marcel Jouhandeau, well-known for his anti-Semitic lampoon Le Péril Juif (“The Jewish Peril”), published in 1938. Florence was the third wife of Frank Jay Gould, the son of Jay Gould, one of the original Robber Barons. She entertained Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald, Joseph Kennedy, and many Hollywood stars, like Charlie Chaplin, who became her lover. Florence became embroiled in a notorious money-laundering operation for fleeing high-ranking Nazis in France, but later managed to avoid prosecution and became a significant contributor to the Metropolitan Museum and New York University. She also became friends with friends like Estée Lauder.[167] Jünger also frequented the George V luxury hotel, where a roundtable of French and German intellectuals gathered, including the writers Morand, Cocteau, Montherlant, as well as the publisher Gaston Gallimard, and Carl Schmitt.[168]

Biographer James S. Williams describes Cocteau’s politics as “naturally Right-leaning.”[169] During the Nazi occupation of France, collaborationist and right-wing writers and critics denounced him as anti-French and a “Jewified” lover of “negroids.”[170] Cocteau eventually sought protection from those among the occupiers whom he considered Francophile, cultured and influential. They included Otto Abetz, Lieutenant Gerhard Heller, Bernard Radermacher, the artistic and personal representative of Joseph Goebbels, and Ernst Jünger, who acknowledged Cocteau as the most important French literary figure in Germany. Jünger became close to Cocteau, although he considered him “tormented like a man residing in his own particular hell, yet comfortable.”[171]

During the Nazi occupation, Cocteau’s friend Arno Breker (1900 – 1991)—Hitler’s favorite artist—convinced him that Hitler was a pacifist and patron of the arts with France’s best interests in mind. Writing privately in his diary, Cocteau accused France of disrespect and ingratitude towards the Führer who loved the arts and all artists. Cocteau even considered the possibility that Hitler, who was still unmarried, might be a homosexual, and might be sublimating his repressed sexuality by supporting such artists as Breker. Cocteau praised Breker’s sculptures in an article entitled “Salut à Breker” published in 1942. As a consequence of the public repercussions of what became known as “the Breker Affair,” Cocteau was branded in 1944 even by the BBC as a collaborator. Cocteau’s friend Max Jacob died from pneumonia in 1944 after a month’s internment on his way to Auschwitz at the transit camp for Jews in Drancy. Cocteau had attempted to no avail to exercise his influence on Otto Abetz by formulating a petition on Jacob’s behalf, who had contact with key Germans in the deportation process.[172]

At the end of the winter of 1944, in the midst of the ruins of the war, Jean Paulhan, who had been the main architect of René Guénon’s entry into Gallimard, received the manuscript of the Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, which he found to be “splendid.”[173] Disgusted by the collaboration, Pierre Drieu la Rochelle also became passionate about Guénon’s work in the last part of his life, bitterly regretting not having met Guénon earlier. The certainty of a single Tradition behind all religions brought some comfort before his suicide in 1945.[174]

After the liberation of France, the principals of Worms & Cie were investigated for possible collaboration with the Germans. Hypolite Worms was arrested on September 8, 1944. He was released on January 21, 1945, and the charges dismissed on October 25, 1946. The inquiries found that Worms & Cie Banking Services had only played a small and involuntary role in financing for the Germans.[175]

[1] Michael Sordet. “The Secret League of Monopoly Capitalism,” Schweiner Annalen No. 2, 1946- 47; cited in “The People’s Front.” The Nation (November 9, 1946).

[2] Henry Chavin. Rapport confidentiel sur la société secrète polytechnicienne dite Mouvement synarchique d’Empire (MSE) ou Convention synarchique révolutionnaire (1941), p. 8.

[3] Olivier Dard. Jean Coutrot: de l'ingénieur au prophète (Presses Univ. Franche-Comté, 1999), p. 335, 347.

[4] Henry Chavin. Rapport confidentiel sur la société secrète polytechnicienne dite Mouvement synarchique d’Empire (MSE) ou Convention synarchique révolutionnaire (1941), p. 8.

[5] Sharon Zukin & Paul Dimaggio. Structures of Capital: The Social Organization of the Economy (Cambridge University Press, 199), p. 360; Johan Heilbron. French Sociology (Cornell University Press, 2015), p. 119.

[6] Chavin Report, p. 6.

[7] H.G. Wells. “Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought” (New York: Harper and Row, 1902), p. 285.

[8] André Ulmann & Henri Azeau. Synarchie et pouvoir (Julliard, 1968), p. 63.

[9] Lynn Picknett & Clive Prince. “Synarchy: The Hidden Hand Behind the European Union,” New Dawn, (March 15, 2012).

[10] Chavin Report, p. 12.

[11] “The People’s Front.” The Nation (November 16, 1946).

[12] Geoffrey de Charney. Synarchie (Paris: Medicis, 1946), Appendix; cited in Picknett & Prince, The Sion Revelation, p. 361.

[13] Lachman. Politics and the Occult, p. 193.

[14] “The People’s Front.”

[15] “Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism.” Press for Conversion. Issue 53 (April 2004).

[16] “Sabotage, Recruiting For Free France Present Problems To Nazis In Paris.” Daily News (Huntingdon, Pa. August 23, 1941).

[17] Ceci. “Une banque collaborationniste : la banque Worms.” Agora (October 30, 2007). Retrieved from

https://www.agoravox.fr/actualites/politique/article/une-banque-collaborationniste-la-30816

[18] Michael Sordet. “The Secret League of Monopoly Capitalism,” Schweiner Annalen No. 2, 1946- 47; cited in “The People’s Front.” The Nation (November 9, 1946).

[19] Interview with Annie Lacroix-Riz. “le choix de la défaite.” Nouvelle Solidarite (July 28, 2006).

[20] Esther Benbassa. The Jews of France: A History from Antiquity to the Present (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1999), p. 104.

[21] Picknett & Prince. The Sion Revelation, p. 362.

[22] Ibid., p. 369.

[23] Zam Bhotiva. Asia Mysteriosa: La Confraternita dei Polari e l’Oracolo della Forza Astrale (Edizioni Arkeios, 2013).

[24] Picknett & Prince. The Sion Revelation, p. 369.