13. The Aufbau

Stabbed in the Back

Aleister Crowley and fellow British agent George Sylverster Viereck shared an acquaintance in Thule Society member General Erich Ludendorff. Around 1925, Crowley and Ludendorff met and they discussed “Nordic Theology,” including the occult significance of the swastika.[1] According to Crowley’s notes, Ludendorff “almost certainly got the [Swastika] from us. I personally had suggested it to Ludendorff in ‘25 or ‘26.”[2] Crowley famously also wrote in a 1933 article for the Sunday Dispatch, “before Hitler was, I am.” Crowley also believed Hitler’s Mein Kampf was inspired by his own The Book of the Law. Crowley marked the pages of his copy Hermann Rauschning’s Hitler Speaks—available at the Warburg Institute—which showed that he believed that Hitler’s “table talk” was Thelemically-inspired.[3] One member of Hitler’s inner circle claimed that several meetings took place between Crowley and Hitler, a claim repeated by Réne Guénon in a letter to Julius Evola in 1949.[4]

Crowley regarded himself the “proper man” that Hitler envisioned, as he wrote to Viereck in 1936:

Hitler himself says emphatically in Mein Kampf that the world needs a new religion, that he himself is not a religious teacher, but that when the proper man appears he will be welcome.[5]

During World War I, Viereck had been in touch with leaders on both sides of the conflict, including Ludendorff—then Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II and top military official—while simultaneously remaining in touch with their counterparts among the allies, like Sir William Wiseman, the head of British Intelligence in the US, President Woodrow Wilson and his advisor “Colonel” Edward Mandell House, as well as the rest of the “Big Four” which included French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, who wrote the terms of the new peace that resulted from Germany’s defeat at the end of World War II in 1918.

On September 29, 1918, the German Supreme Army Command at Imperial Army Headquarters in Spa of occupied Belgium informed Kaiser Wilhelm II and the Imperial Chancellor, Count Georg von Hertling, that the military situation facing Germany was hopeless. Ludendorff claimed that he could not guarantee that the front would hold for another two hours and demanded a request be given to the Entente for an immediate ceasefire. In addition, he recommended the acceptance of the main demands of Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, including putting the Imperial Government on a democratic footing, hoping for more favorable peace terms.[6] The Fourteen Points were well received in the United States and Allied nations and even by Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, as a landmark of enlightenment in international relations.[7] Wilson subsequently used the Fourteen Points as the basis for the harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles negotiated a the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, which ruined the German economy, leading to depression and eventually providing the Round Table the pretext to bolster the rise of their agent Hitler and the Nazis.

As explained by Ian Kellogg in The Russian Roots of Nazism, in the period leading up to the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, the far right in the German and Russian Empires had failed politically. Many of the supporters of the Romanov monarchy, known as White Russians, many of them members of Sovereign Order of Saint John of Jerusalem (SOSJ), fled and found their way to Germany. Consolidating themselves within a conspiratorial organization known as the Aufbau: Wirtschafts-politische Vereinigung für den Osten (“Reconstruction: Economic-Political Organization for the East”)—in collaboration with Soviet and British double-agents associated with Round Tabler Sir William Wiseman—they teamed with the Nazis for the overthrow of the governments of Russia and Germany, deemed to be under the threat of the rise of communism, which they believed was part of a Jewish conspiracy outlined in the Protocols of Zion, and which had been responsible for the toppling of the Russian aristocracy and the rise of the Bolsheviks.

After Germany had lost World War I in 1918, the German Revolution of 1918–1919 ended the monarchy and the German Empire was abolished and a democratic system, the Weimar Republic, was established in 1919 by the Weimar National Assembly. Although he had been responsible for unleashing Lenin, who led the Bolsheviks to victory in Russia in 1917, and supported acceptance of Wilson’s Fourteen Point, after the war, Aufbau and Thule Society member, General Erich Ludendorff—Kaiser Wilhelm II’s top military official, as well as a friend of George Sylvester Viereck and later Aleister Crowley—became a prominent nationalist leader, and a promoter of the Stab-in-the-back myth, which posited that the German Army did not lose World War I on the battlefield but was instead betrayed by the civilians on the home front, especially by Marxists, Bolsheviks, Freemasons and Jews who were furthermore responsible for the disadvantageous settlement negotiated for Germany in the Treaty of Versailles.

It has been suggested that the origin of the phrase “stabbed in the back” was suggested to Ludendforff by Sir Neill Malcolm, the head of the British Military Mission, whom he met in Berlin in 1919, after Ludendorff had described to him his many excuses for the German defeat.[8] To völkisch German right, the expression “stab in the back” recalled Wagner’s 1876 opera Götterdämmerung, in which Hagen murders his enemy Siegfried—the hero of the opera—with a spear in his back.[9] When the Nazi Party came to power in 1933, they made the legend an integral part of their official history of the 1920s, portraying the Weimar Republic as the work of the “November criminals” who stabbed the nation in the back to seize power while betraying it.

The völkisch German right were unable to gather a mass following, nor could they replace the Kaiser with a military dictatorship under Ludendorff in 1917. In Imperial Russia, the far right “Black Hundred” movement gained some initial popular successes in the aftermath of the Revolution of 1905. The Black Hundred movement soon split into factions, however, that could not suppress the Tsar’s abdication and the Bolshevik seizure of power in 1917. It was only after the Bolsheviks had come to power and Germany had lost World War I that the combined German and White Russian émigré far right began to thrive, primarily by blaming these “catastrophes” on the Jews, and promoted the Protocols of Zion in support of their accusations.

White Russians

Supporters of the Black Hundreds marching in Odessa shortly after the October Manifesto 1905

The Aufbau was formed in 1918 by former members of the Black Hundred, who brought together White Russian émigrés and early German National Socialists who aimed to overthrow the governments of Germany and the Soviet Union, replacing them with authoritarian far-right regimes. The White émigré community were comprised of anti-communists who left Russia in the wake of the Russian Revolution and Russian Civil War. Important White émigré members of the Aufbau included First Secretary Erwin von Scheubner-Richter, Boris Brasol, Pavlov Bermondt-Avalov, Fyodor Vinberg, Pyotr Shabelsky-Bork, General Vladimir Biskupsky, and Thule Society members General Erich von Ludendorff and Alfred Rosenberg, who introduced the Nazis to The Protocols of Zion, forming the basis of their anti-Semitism. The Aufbau drew on the apocalyptic ideas of Russian slavophile authors, like Fyodor Dostoevsky and Vladimir Solovyov. Dostoevsky, explains Michael Kellogg, “crystallized conservative revolutionary ideology in Imperial Russia much like Wagner shaped völkisch views in Germany.”[10] Building upon the anti-Semitic ideas of Dostoevsky, the fundamental views of Aufbau as expressed by Scheubner-Richter, Vinberg, and Rosenberg, maintained that an insidious Jewish world conspiracy of Freemasons and Jews manifested itself as the Bolshevik Revolution and the Soviet Union.[11]

The chief promoter of this idea was Boris Brasol. Brasol and Reilly were both part of the Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem (SOSJ). The historic Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem was legitimately continued outside of Russia by Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich (1876 – 1938).[12] Russian émigrés who went into exile following the Revolution in 1917 have attempted to keep the Order alive. As part of the Counter Revolution planned by Russian Guard officers, General Count Keller, an influential member of the SOSJ, singlehandedly started the resistance of the Knights of Malta whose historical charge was the defense of Imperial Russia and the Romanov family.

Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich (1876 –1938)

Grand Duke Kirill was married to his paternal first cousin, the granddaughter of Queen Victoria, Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who was an ardent supporter of the Aufbau and carried on an affair with its vice-president, Vladimir Biskupskii.[13] Kirill and former Black Hundred member Pavlov Bermondt-Avalov, who served under Keller, planned to join with German forces to drive the Bolsheviks out of the Baltic. Grand Duke Kirill continued to finance the SOSJ venture with the help of the American Grand Priory of the order, whose intimate associates included the brothers John Foster and Allen Welsh Dulles. Both were working directly for SOSJ member William Nelson Cromwell, one of the founding partners of Sullivan & Cromwell in 1879. In 1919, Bermondt—supported by the German Order of St. John, the Johanniter Orden, and Grand Duke Kirill and American financier J.P. Morgan, Jr., who belonged to the American branch of the Order of Saint John—became commander-in-chief of the Russian Imperial Army. Other prominent in the OSJ at this time included J.P Morgan, Sr., John Jacob until his death on the Titanic, and the extended Cornelius Vanderbilt and Chicago Crane families.[14]

OSJS member J.P. Morgan Jr. (1867 – 1943)

In 1919, Bermondt joined with German Major General Rüdiger von der Goltz to form what was to be called the Western Volunteer Army. The aim of this combined German and White Russian force was to advance into the heartland of Bolshevik Russia in defiance of both the Entente and the German government. Goltz wished Bermondt’s forces to collaborate with the White armies of the British-backed General Anton Denikin in the Ukraine and Admiral Aleksandr Kolchak in Siberia. It numbered some 200,000 men, almost a quarter of whom were nationals of the Allied powers, including 7,500 Americans and 1,600 British.[15] Together, these forces were to overthrow the Bolshevik regime and to create a pro-German Russian state that the Germans could ally with against the Entente.[16]

Later joining the Aufbau, Bermondt became head of the Russian Fascist Party in Germany, called the Russian National Liberation Movement (ROND). Mikhail Kommissarov, who ultimately helped to establish the Aufbau, was a prominent member of the Saint Petersburg Okhrana, and provided support to the right-wing Black Hundred Union of the Russian People. After the outbreak of socialist revolution in the Russian Empire in 1905, Kommissarov established a clandestine printing press in the basement of the Okhrana headquarters, which he used to print anti-Semitic leaflets calling for pogroms against the Jews.

Judeo-Masonic Conspiracy

Boris Brasol

Cover of first book edition of the Protocols, “The Great within the Minuscule and Antichrist.”

Brasol was chiefly responsible for the dissemination of the Protocols in the English-speaking world. Brasol, Arthur Cherep-Spiridovich and Reilly were connected through the so-called Anti-Bolshevik League with other rightist White Russians and their fascist supporters in a global network stretching across Europe and the Americas with branches as far away as Japan.[17] While many of Reilly’s business and espionage associates were also Jewish, he openly denounced Jewish dominance in American banking and commerce, the pro-Bolshevik sympathies of many Jewish immigrants, and the American immigration laws that allowed entry to such people. As summarized by Richard Spence, “Jew or no Jew, the history of the SOSJ claims Reilly as another member of the order, and makes the Anti-Bolshevik League one more gambit of the order’s secretive intelligence-propaganda activities, activity that also included dissemination of the Protocols.”[18]

At the time of his death, Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich was the Military Governor General of Moscow and had worked to uncover the cells of anarchists who were assassinating government officials which included his own father Czar Alexander II. His wife Grand Duchess Elizabeth, sister of Czarina Alexandra, was involved in the research to unmask the anarchists and this interest brought them both into contact with Sergei Nilus, one of the earliest men to produce a copy of the Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion and Grand Duchess Ella introduced him and the Protocols to her sister and to Tsar Nicholas II. Cherep-Spiridovich was thereby one of the earliest members of any Intelligence Service to see the Protocols. He was given the mandate by the Russian Imperial family to investigate the matter fully and to spread the alarm about “the hidden hand” of international Zionism and its plan to gain global control through the elimination of the Christian Church.

In March 1918, Brasol secured employment in the New York office of the War Trade Board’s Intelligence Bureau as a “special investigator” in charge of “investigations of importance and of the most confidential nature,” that made use of his “knowledge of European political and territorial problems” and the “chaotic conditions in Siberia and Russia.”[19] Brasol resigned from the bureau in April 1919, and immediately took up a new post with the Army’s Military Intelligence Division (MID) as a special assistant to its chief, Gen. Marlborough Churchill a distant relative of Winston Churchill. Churchill was very concerned with the “Bolshevik Menace” and receptive of Brasol’s suggestion that a Jewish conspiracy was behind it. In December 1919, Brasol submitted a report that described an “international German Jewish gang,” allegedly working out of Stockholm, that aimed at “world socialist revolution.”[20] It consisted of twelve leaders, a “Jewish dozen,” which included Trotsky, Jacob Schiff, and Max Warburg.[21]

Several authors link Brasol with the first American edition of the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. Brasol attributed the downfall of the Russian monarchy to a Jewish conspiracy outlined in the Protocols of Zion, and also claimed that Jewish bankers like the Warburgs had been behind the Bolshevik Revolution. The White Russian investigators discovered that the Tsaritsa had possessed a copy of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion by Sergei Nilus, who was a member of the Black Hundred. They also noted that she had drawn a swastika in her room. A report was compiled which eventually appeared in the Thule Society’s Völkischer Beobachter. An article in a September 1920 edition of the newspaper, soon before it would became the official publication of the Nazi Party, claimed that Jews had murdered the Tsar and his family.[22]

Natalie De Bogory (right)

Casimir Pilenas, who worked simultaneously with Sir William Wiseman and Pyotr Rachkovsky, head of the Russian Okhrana in Paris, and another purported lead conspirator in the forging of The Protocols, was one of three people who would play important roles in Brasol’s dissemination of an American edition.[23] Brasol’s other important associate was Natalie De Bogory, the daughter of Vladimir Karpovich Debogory-Mokriyevich, who had been imprisoned under the tsarist government for revolutionary activities. Natalie married Albert Sonnichsen, a Jewish writer, and moved to the United States. Sonnichsen was a member of the Jewish Cooperative League, a precursor to the Cooperative League of America, which was created to unify all the cooperatives into a coordinated movement.[24] By the time World War I rolled around, Natalie was the personal assistant to Dr. Sergei Syromiatnikov, the Russian imperial government’s chief public relations man in the U.S. as well as a collaborator with the Okhrana.[25] Syromiatnikov had also served as a foreign correspondent as a member mission of Gurdjieff’s friend Esper Ukhtomskii to the Far East. De Bogory eventually moved to Paris and worked as Sol Hurok’s publicity person in Europe and eventually a writer for the International Herald Tribune.

According to Robert Singerman, at the end of 1917, a New York physician and member of the American intelligence community, Dr. Harris Ayres Houghton, came into contact with “Black Hundred Russians” and through their influence hired De Bogory to work in his office. Soon after, either from Brasol or some other officer, De Bogory obtained a Russian copy of The Protocols, which Houghton assigned her to translate into English.[26] In some versions of the story, Brasol assisted or guided De Bogory in this effort. Either way, two English versions of The Protocols were the result. The first, Brasol’s was The Protocols and World Revolution, which appeared in Boston in 1920. The second was Houghton’s own edition, Praemonitus, Praemunitus: The Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion, which came out in New York later the same year. Brasol soon circulated The Protocols in American government circles, specifically diplomatic and military, in typescript form, a copy of which is archived by the Hoover Institute.[27]

Leslie Fry

Another important associate of Brasol was Leslie Fry, primarily known for her authorship of Waters Flowing Eastward, which attempts to prove that The Protocols are part of a plot to destroy Christian civilization. Fry, alias Paquita Louise De Shishmareff, was born out of wedlock as Louise Chandor. Her father, John Arthur Chandor, was the son of a Lazso Chandor, an Hungarian immigrant to the United States who had a reputation of being “an adventurer of the most dangerous character,” and there were also claims that he was Jewish.[28] She married a captain of the Russian Imperial Army, and supposedly the Grand Duchess Xenia Aleksandrovna—the sister of Emperor Nicholas II—and her husband Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich acted as witnesses. Xenia was the mother-in-law of Felix Yusupov and a cousin of Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich of Russia, who together killed Rasputin. The couple lived in Tsarskoye Selo, in close relation with the royal family.[29]

Fry had two sons, Kirill and Misha. Kirill’s godmother was Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna of Russia, the cousin of Grand Duke Kirill’s wife, and therefore also a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, as well as an older sister of Alexandra, the last Russian Empress. Elizabeth’s husband was Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia, the fifth son of Alexander II of Russia, and an uncle to Emperor Nicholas II. Elizabeth was also a maternal great-aunt of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, the consort of Queen Elizabeth II. In the 1960s and 1970s, Kirill styled himself Prince Kirill de Vassilchikov-Shishmareff, Comte de Rohan-Chandor, where he was Lieutenant Grand Master in the SOSJ and endeavored to track down the heirs to the Romanov inheritance. Kirill also claimed to have be in contact with Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia, his former playmate in Tsarskoye Selo, who had survived the massacre of the royal family in Yekaterinburg.[30]

Edith Starr Miller, Lady Queenborough (1887 – 1933)

In 1921, Fry published an article in La Vielle France in which she claimed that the author of The Protocols was Ahad Haam (1856 – 1927), who wrote them in Hebrew and disseminated them among the Jews of Odessa as early as the 1890s. Haam was the pen name of Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg, one of the foremost pre-state Zionist thinkers, who was said to have been a member of the Alliance Israëlite Universelle.[31] Ginsberg’s originally Hebrew version would have been translated into Russian, and finally French for the members of the Alliance Israëlite Universelle, and passed at a secret meeting of B’nai B’rith, which purportedly took place in 1897 during the first Zionist Congress.[32]

In England, Fry associated with Nesta Webster and Edith Starr Miller (Lady Queenborough), author of Occult Theocracy, which put forward the view that Jews and Freemasons were to blame for World War I and the rise of Bolshevism. In Paris she kept contact with Urban Gohier, editor of the anti-Semitic journal La Vielle France, best known for his publication of The Protocols, and Ernest Jouin, the principle exponent of Catholic anti-Semitism in the interwar period, who published the works of Jacob Brafman.[33] Lady Queenborough and Jouin were among a number of proponents of a Jewish conspiracy who were affiliated with the SOSJ, along with Paquita de Shishmareff, Fr. Denis Fahey, John B. Trevor, Jr. and Princess Julia Grant Cantacuzene. Jouin also translated The Book of the Kahal of Jacob Brafman, which claimed that the kahal was controled by the Alliance Israélite Universelle, which was based in Paris and then under the leadership of Adolphe Crémieux, Grand Master of Memphis-Mizraim. Craig Heimbichner, writing in the August 2003 Catholic Family News, states that Monsignor Ernest Jouin is said to have intervened personally with Emperor Franz Joseph to ask for the Jus exclusivae to be invoked, having procured some evidence that Cardinal Rampolla had at least a close affinity with the Freemasons.[34]

Monsignor Ernest Jouin (1844 – 1932)

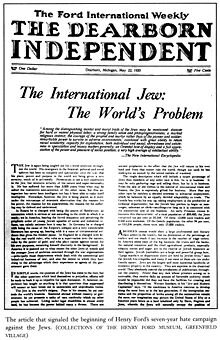

Jouin also appears to have been associated with Cherep Spiridovich. [35] Cherep-Spiridovich was the author of a 1926 tract called The Secret World Government of the Hidden Hand, positing a concise conspiracy consisting of 300 Jewish families, and was intimately involved in promoting The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion in the United States. According to Lord Alfred Douglas, well-known men like Henry Ford and newspapers like the Financial Times in London took Cherep-Spiridovich seriously and helped him to reach a fairly wide public.[36] As recorded in the New York World published on February 17, 1921, Ford famously said: “The only statement I care to make about the PROTOCOLS is that they fit in with what is going on. They are sixteen years old, and they have fitted the world situation up to this time. THEY FIT IT NOW.” Ford was also a Freemason.[37]

Norman Hapgood identified Cherep-Spiridovich and Brasol as the two most influential figures behind Ford. According to Hapgood, Cherep-Spiridovich, at one point lived in Detroit and worked for Ford.[38] Hapgood also revealed that Brasol’s and Ford’s anti-Semitic crusade had been supported by a prominent Jewish lawyer, named Maurice Leon.[39] Born in Beirut and educated in Paris, Leon was the stepson of Columbia professor Richard Gottheil, the “reluctant father of American Zionism,” who founded the Federation of American Zionist Societies of New York (FAZ) in 1897, and which included known Sabbateans like Louis Brandeis and Rabbi Stephen Wise.

Henry Ford (1863 – 1947)

In 1920, Fry had also been employed by Henry Ford’s Dearborn Publishing Company. She offered to sell Ford’s personal secretary Ernest G. Diebold the “originals” of The Protocols, allegedly stored in a safety deposit box in a Shanghai bank for $25,000.[40] At this time, she was supposedly commissioned by Ford to undertake an investigation of the origin of The Protocols, and according to Jewish historian Elias Tcherikower she travelled to Russia to meet with Sergei Nilus.[41] The results of her research were compiled in Waters Flowing Eastward. The book contained the story of Yuliana Glinka purchasing a copy from Joseph Schorst (Shapiro), a member of Joly’s Misraim Lodge, which allegedly mainly attracted Jews.

Ford himself later published The International Jew, and had been implicated in the financing of Hitler. In Who Financed Hitler, James Pool proposed Brasol was a bagman between Ford and Hitler. The go-between was a friend of Dietrich Eckart and a fellow-member of the Aufbau, Kurt Ludecke. An ardent German nationalist, Ludecke was known to be a playboy as well as an international traveler and fundraiser for the Nazi party.[42] Ludecke had offered his services to Hitler as an envoy to Benito Mussolini soon after the Italian dictator marched on Rome and rose to power in Italy. Ludecke also met with Henry Ford in Detroit in the mid-1920s, with the intention of soliciting funds for Hitler. Ludecke’s introduction was provided by Siegfried and Winifred Wagner, the son and daughter-in-law of the great composer Richard Wagner in New York, who were Hitler supporters.[43]

Norman Hapgood, editor of Collier’s Weekly and Harper’s Weekly married Isabel Reynolds who was in regular correspondence with Dr. Sergei Syromiatnikov, whose personal assistant was Boris Brasol’s partner in conspiracy mongering, Natalie De Bogory.[44] Starting in June 1922, Hapgood ran a series of exposes in Hearst’s International entitled “The Inside Story of Henry Ford’s Jew Mania,” which reported that in 1921, Ludecke, “one of Hitler’s lieutenants,” came to the United States, where he met Brasol, who was “then the Grand Duke [Kirill’s] representative in the United States [who gave] me a letter of Introduction to [Kirill] and other Russians.”[45] Ludecke then travelled back to Europe to request Kirill for funds to help the budding Nazis. The expectation was that once Hitler succeeded to power, he would repay the debt by defeating the Bolsheviks and restoring the Romanovs to the throne. During 1922-23, Kirill supplied half a million gold marks to “support nationalist German-Russian undertakings” via General Erich Ludendorff. Pool supposed that the money was really Ford’s, conveyed to Europe by Brasol and “laundered” through Kirill. The key to this arrangement, Pool explains, was Brasol’s many trips to Europe, which afforded him “plenty of opportunity to convey substantial sums of Ford’s money to Hitler.”[46]

Beer Hall Putsch

Ludendorff (center) with Hitler and other early Nazi leaders and prominent radical German nationalists (Munich, 1924)

In Germany, Fry was in contact with Aufbau member Fyodor Viktorovich Vinberg (1868 – 1927), who was apparently responsible for Hitler’s conversion to the idea of a worldwide Jewish-Bolshevist conspiracy.[47] The Protocols thus became a part of the Nazi propaganda effort to justify persecution of the Jews. In The Holocaust: The Destruction of European Jewry 1933–1945, Nora Levin states that “Hitler used the Protocols as a manual in his war to exterminate the Jews”:

Despite conclusive proof that the Protocols were a gross forgery, they had sensational popularity and large sales in the 1920s and 1930s. They were translated into every language of Europe and sold widely in Arab lands, the US, and England. But it was in Germany after World War I that they had their greatest success. There they were used to explain all of the disasters that had befallen the country: the defeat in the war, the hunger, the destructive inflation.[48]

As explained by Michael Kellogg, “The Protocols’ warnings of an insidious Jewish plot to achieve world domination greatly affected völkisch Germans and White émigrés, including Hitler’s mentors Eckart and Aufbau member Alfred Rosenberg.”[49] Rosenberg, who was also a Baltic German, led the Nazi Party during Hitler’s imprisonment following the Aufbau-backed Beer Hall Putsch. Ultimately, he directed Germany’s rule over formerly Soviet areas during World War II, and participated in the Final Solution through his post as Reichsminister für die besetzten Ostgebiete (State Minister for the Occupied Eastern Territories). According to Kellogg, Rosenberg “later helped to shape National Socialist ideology by synthesizing völkisch German ideas with White émigrés views.”[50]

Alfred Rosenberg (1893 – 1946)

Many of Rosenberg’s own ideas were said to have been lifted from the writings of his friend Vinberg. Kellogg describes Eckart and three Aufbau members, Scheubner-Richter, Vinberg, and Rosenberg, as the “four writers of the apocalypse,” who “influenced National Socialist ideology by adding White émigré conspiratorial-apocalyptic anti-Semitism to existing völkisch redemptive notions of Germanic spiritual and racial superiority.”[51] Vinberg called for “Aryan peoples” to unite against the “Jewish plan for world domination,” and advocated for Russia’s return to the strong authority of the Tsar, which he hoped to restore with German help. Vinberg had lengthy and detailed discussions with Adolf Hitler on ideological matters. Like many in the Russian right, Vinberg was much influenced by the anti-Semitic ideas of Fyodor Dostoyevsky. During World War I, Vinberg commanded the Second Baltic cavalry regiment. He became personally acquainted with the wife of Nicholas II, Tsarina Aleksandra Romanov, with whom he was rumored to have had an affair.[52]

After the Bolshevik Revolution, Vinberg was put in prison for his role in an alleged plot to overthrow the Provisional Government. In prison, Vinberg met fellow Aufbau member, Lieutenant Pyotr Shabelsky-Bork, formerly of the Black Hundred, who had participated in the official investigation of the Bolshevik murder of the Tsarist family. On May 1, 1918 Vinberg and Shabelsky-Bork were amnestied on the occasion of “international proletariat solidarity.” Shabelsky-Bork arrived in Berlin in early 1919 with a copy of the The Protocols, which he gave for translation and publication in German to the völkisch publicist Ludwig Müller von Hausen, a member of Fritsch’s Germanenorden. Hausen sent The Protocols to the Völkisch Observer, who ran a large front-page article, “The Secrets of the Wise Men of Zion,” in April 1920.[53] The “fighting paper of the National Socialist movement of Greater Germany,” as it called itself, the Völkisch Observer, which was owned by von Sebottendorf, had its origin as the Munich Observer of the Thule Society.

Dietrich Eckart (1868 – 1923)

By December 1920, the Völkisch Observer was heavily in debt, and the Thule Society were open to an offer to sell the paper to the Nazis. Major Ernst Röhm and Dietrich Eckart persuaded Röhm’s commanding officer, Major General Franz Ritter von Epp, to purchase the paper for the Nazi Party. In 1921, Adolf Hitler, who had taken full control of the NSDAP earlier that year, acquired all shares in the company, making him the sole owner of the publication.[54] Alfred Rosenberg became the editor in 1923.

In The Myth of the Twentieth Century, the most important Nazi book after Mein Kampf, Rosenberg referred to Atlantis as a lost land or at least to an Aryan cultural center.[55] Rosenberg, who was inspired by the theories of Arthur de Gobineau by Houston Stewart Chamberlain, believed that God created mankind as separate, differentiated races in a cascading hierarchy of nobility of virtue. Rosenberg’s racial interpretation of history concentrates on the negative influence of the Jewish race in contrast to the Aryan race. In addition to Eckhart, other influences included the Nietzsche’s anti-modernist “revolutionary” ideas, Wagner’s Holy Grail romanticism inspired by the neo-Buddhist thesis of Arthur Schopenhauer, Ernst Haeckel, and Nordicist Aryanism. Rosenberg spends much time discussing the Cathars. The titular “myth” is “the myth of blood, which under the sign of the swastika unchains the racial world-revolution. It is the awakening of the race-soul, which after long sleep victoriously ends the race chaos.”[56]

Eckart and Rosenberg both attended meetings of the Thule Society in Munich, and became aware of Hausen’s translation of The Protocols in late 1919, even before parts of it were published in the Völkisch Observer, which Rosenberg had effectively taken over. By December 1920, the paper was heavily in debt and Eckart initiated its purchase by the Nazi Party. According to Kellogg, “The Protocols significantly shaped Eckart’s outlook, and Eckart’s role in influencing Hitler’s anti-Bolshevik, anti-Semitic ideas in league with Rosenberg warrants greater attention.”[57] In a March 1920 edition of his newspaper Auf gut deutsch: Wochenschrift für Ordnung und Recht (“In Plain German: Weekly for Law and Order”), Eckart urged nationalist Germans to pay greater attention to Prizyv (“The Call”), the monarchist exile newspaper founded by Vinberg in 1919, which sought to foster “close friendly relations between Germany and Russia.”[58] A November 1919 edition of The Call, featured an essay titled “Satanists of the Twentieth Century,” which claimed that the “Jew Trotsky,” the Soviet Commissar for War, and other high-ranking Soviet leaders had held a black mass within the walls of the Kremlin in Moscow, in which they prayed to the devil for help in defeating their enemies the White Russians.

Munich Marienplatz during the failed Beer Hall Putsch

The long-term influence of the anti-Semitism and anti-Bolshevism of the Aufbau has been traced to the implementation of the Final Solution and in Hitler’s disastrous decision to divert troops away from Moscow towards the Ukraine in 1941.[59] Aufbau leader Erwin von Scheubner-Richter (1884 – 1923), a Baltic German from the Russian Empire, was an early member of the Nazi Party and served as Hitler’s chief advisor on foreign policy matters and as one of his closest counselors. Scheubner-Richter had introduced Hitler to General Erich von Ludendorff. According to Michael Kellogg, after the defeat of Bermondt-Avalov’s forces, Wolfgang Kapp and Ludendorff used demobilized Germans and White émigrés to undermine the Weimar Republic. In March 1920 , at the behest of Karl Mayr—the General Staff officer of the Reichswehr, who first hired Hitler to infiltrate the DAP—Hitler and Eckart flew to Berlin to meet Kapp and take part in the Kapp Putsch of March 1920, along with Ludendorff, Scheubner-Richter, Biskupsky, Vinberg, Shabelsky-Bork.[60] While the Kapp Putsch failed in Berlin, it succeeded in Munich, and it set the stage for increased cooperation between völkisch Germans, including National Socialists, and White émigrés there.

At the end of September 1923, Scheubner-Richter provided Hitler with a lengthy plan for revolution, writing: “The national revolution must not precede the seizure of political power; the seizure of the state’s police power constitutes the promise for the national revolution” and “to lay hands on the state police power in a way that is at least outwardly legal.”[61] Along with Alfred Rosenberg, he devised the plan to drive the German government to revolution through the Beer Hall Putsch, the failed coup attempt by Hitler—along with Ludendorff and other Kampfbund leaders—to seize power in Munich, on November 8–9, 1923. About two thousand Nazis marched to the center of the city, where they confronted the police, resulting in the death of sixteen Nazis and four police officers. Scheubner-Richter was shot in the lungs and died instantly, at the same time dislocating Hitler’s right shoulder. Hitler escaped immediate arrest and was spirited off to safety in the countryside. After two days, he was arrested and charged with treason.

Mein Kampf

Thule Society members Karl Haushofer and Rudulf Hess, later Hitler’s deputy Führer

Hitler’s arrest was followed by a 24-day trial, which was widely publicized and gave him a platform to promote his nationalist sentiment to Germany and the world. Hitler was found guilty of treason and sentenced to five years in Landsberg Prison, where he visited by Eckart’s friend and fellow Aufbau member Karl Haushofer (1869 – 1946), a fellow member of the Thule Society and another major influence on Hitler’s thinking. After serving as a commanding officer in World War I, Haushofer retired with the rank of major general in 1919. However, he became disillusioned after Germany’s loss and severe sanctioning.

Around the same time, Haushofer forged a friendship with the young Rudolf Hess, a member of the Thule Society, who would become his scientific assistant and later the deputy leader of the Nazi Party. Felix Kersten claimed that Hess “… was vegetarian, surrounded himself with clairvoyants and astrologers, and despised official medical views.”[62] Hess also studied the prophecies of Nostradamus and kept a dream diary. Fascinated by meditation and animal magnetism, Hess performed yoga-like exercises to re-energize his aura, and practiced self-hypnosis to fortify will power. His wife Ilse Prohl complained of feeling neglected because he usually abstained from sex in an effort to conserve “prana.” Kurt Ludecke was shocked to hear that Ernst Röhm, Otto Strasser and others referred to Hess as “Fraulein Anna,” because they believed he was carrying on a homosexual affair with Hitler. Ernst Hanfstaengl stated that it “is beyond doubt that (Hitler) had a liaison with Hess.”[63] Hess’ wife Ilse Prohl complained that Hess made her feel like a “convent school girl.” Ilse later told Hans-Adolf Jacobsen that Haushofer and Hitler both made her “a trifle jealous.” [64]

Munich doctor Dr. Ludwig Schmitt served as both a breathing therapist and astrologer. Other astrologers consulted by Hess included Edouard Hofweber, Ernst Issbener-Haldane, F.G. Goerner, and Karl Ernst Krafft. Hess and Dr. Schulte Strathaus wanted to establish a large Central Institute for Occultism with faculties like a modern university but Hitler rejected the idea.[65] Strathaus as an enthusiastic supporter of the Munich doctor and parapsychologist Albert von Schrenck-Notzing.[66] Schrenck-Notzing, an associate of Freud and an important influence on him, was a German medical doctor and a pioneer of psychotherapy and parapsychology, who had participated in Max Theon’s Cosmic Movement.[67] Schrenck-Notzing was also the founder of the Gesellschaft für psychologische Forschung (“Society for Psychological Research”) with Max Dossier and Wilhelm Hübbe-Schleiden, an associate of Henry Steel Olcott and Annie Besant, who founded the German Theosophical Society, to which belonged Franz Hartmann and Rudolf Steiner.[68] Schulte Strathaus transferred to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.[69]

In Landsberg Prison, Hitler wrote Mein Kampf, dictated to his fellow prisoner Rudolf Hess, in which he combined the theories of Haushofer and those of Alfred Rosenberg, and which he dedicated to Eckart. Like the Völkisch Observer, Mein Kampf was published by Franz Eher Nachfolger, the central publishing house of the Nazi Party. The publishing house was registered by Franz Xaver Josef Eher (1851 – 1918) in 1901. However, the firm was actually founded with the name Münchener Beobachter in 1887. After Eher’s death, Rudolf von Sebottendorf took over the firm in 1918.

Mein Kampf describes the process by which Hitler became anti-Semitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germany.[70] Help in editing the work was also provided by Hanfstaengl.[71] Of The Protocols, Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf:

…[The Protocols] are based on a forgery, the Frankfurter Zeitung moans [ ] every week… [which is] the best proof that they are authentic… the important thing is that with positively terrifying certainty they reveal the nature and activity of the Jewish people and expose their inner contexts as well as their ultimate final aims.[72]

It was in Mein Kampf that Hitler described the “big lie,” a propaganda technique that makes use of a lie so “colossal” that no one would believe that someone “could have the impudence to distort the truth so infamously.” Hitler believed the technique was used by Jews to blame Germany’s loss in World War I on Ludendorff:

But it remained for the Jews, with their unqualified capacity for falsehood, and their fighting comrades, the Marxists, to impute responsibility for the downfall precisely to the man who alone had shown a superhuman will and energy in his effort to prevent the catastrophe which he had foreseen and to save the nation from that hour of complete overthrow and shame. By placing responsibility for the loss of the world war on the shoulders of Ludendorff they took away the weapon of moral right from the only adversary dangerous enough to be likely to succeed in bringing the betrayers of the Fatherland to Justice.[73]

Ludendorff on the cover of Time (November 19, 1923)

Henry Ford is the only American mentioned in Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and Hitler hung a portrait of Ford behind his desk and told the industrialist, on a visit Ford paid to Nazi Germany, that Nazism’s accomplishments were simply an implementation of Ford’s vision.[74] For a time, Ludendorff expressed great admiration for Ford, because of his anti-Semitic propaganda, but when Ford made his public apology to the Jews in 1927, he denounced him and alleged that he had joined the Palestine Lodge of the Freemasons.[75]

Ludendorff was also friendly with Haushofer.[76] Although he had participated with Hitler in their joint putsch in Munich in 1923, Ludendorff denounced his former colleague as a dangerous betrayer of the German people and an agent of the Freemasons. When Ludendorff, Hitler, and their associates in the Beer Hall Putsch stood trial in February 1924, Ludendorff made a long speech to the court, where he declared that the Jewish question is primarily a race question. Ludendorff attributed his defeat in World War I to the intervention of the Jews, supporting his allegations by quoting from the Protocols. The Catholics were protecting the Jews, he said, and the Catholic hierarchy was in league with the Jews and the Freemasons.[77] In 1924, he was elected to the Reichstag as a representative of the NSFB, a coalition of the German Völkisch Freedom Party (DVFP) and members of the Nazi Party, serving until 1928. At around this time, he founded the Tannenberg League, a German nationalist organization which was both anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic, and published literature espousing conspiracy theories involving Jews, Catholics—particularly the Jesuits—and Freemasons.[78]

Ludendorff and his second wife Mathilde von Kemnitz

In 1926, Ludendorff married his second wife Mathilde von Kemnitz, who was interested in Ariosophy and the occult. She began her career criticizing that the experiments of Baron Albert von Schrenck-Notzing were unscientific and that he had been duped by tricks of the medium Eva Carrière.[79] In Insanity Induced Through Occult Teachings (1933), she attacked Schrenck-Notzing’s work and argued that occult practices had been responsible for the development of mental illness in a number of her patients.[80] In spite of her personal opposition to occultism, her involvement in the völkisch movement led her co-operate with a number of occultists, such as the Edda Society of Rudolf John Gorsleben, of which she was a member and whose other members included Friedrich Schaefer, a follower of Karl Maria Wiligut, and Otto Sigfried Reuter, a strong believer in astrology.[81]

Mathilde also included occultists to the Stab-in-the-back legend. In the Fraud of Astrology, she was critical of astrology, arguing that it had always been a Jewish perversion of astronomy and that it was being used to enslave the Germans and dull their reasoning. She was also critical of anthroposophy, in her 1933 essay “The Miracle of Marne.” She and Ludendorff argued that General Helmuth von Moltke the Younger had lost the First Battle of the Marne because he had come under the control of Lisbeth Seidler, a devotee of Rudolf Steiner.[82] The Ludendorffs published books and essays to prove that the world’s problems were the result of Christianity, especially the Jesuits and Catholics, but also conspiracies by Jews and the Freemasons. They founded the Society for the Knowledge of God, a small esoteric society that survives to this day.

[1] Richard B. Spence. Secret Agent 666: Aleister Crowley, British Intelligence and the Occult, p. 194., p. 194.

[2] Peter-Robert Koenig. “The Templar’s Reich Milieu: The Slaves Shall Serve.” www.parareligion.ch (2006).

[3] Lachman. Aleister Crowley.

[4] David Luhrssen. Hammer of the Gods: The Thule Society and the Birth of Nazism (Potomac Books, Inc., 2012), p. 215 n. 17.

[5] Lawren Sutin. Do What Thou Wilt, from the O.T.O. archives; cited in Alan Richardson. Aleister Crowley and Dion Fortune: The Logos of the Aeon and the Shakti of the Age (Llewellyn Worldwide, 2009), p. 81.

[6] Alan Axelrod. How America Won World War I (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018), p. 260.

[7] “Wilson’s Fourteen Points, 1918 - 1914–1920 - Milestones.” Office of the Historian. Retrieved from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/fourteen-points

[8] John W. Wheeler-Bennett (Spring 1938). “Ludendorff: The Soldier and the Politician.” The Virginia Quarterly Review, 14 (2): 187–202.

[9] J. M.Roberts. Twentieth Century: The History of the World, 1901 to the Present (London: Allen Lane/The Penguin Press, 1999), p. 289.

[10] Michael Kellogg. The Russian Roots of Nazism, p. 31.

[11] Ibid., p. 218.

[12] “Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem.” www.osjknights.com (accessed January 26, 2017).

[13] Michael Kellogg. The Russian Roots of Nazism, p. 157.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Giles Milton. Russian Roulette: A Deadly Game: How British Spies Thwarted Lenin’s Global Plot (Hodder & Stoughton, 2014).

[16] Kellogg. The Russian Roots of Nazism, p. 94.

[17] Hugo Turner. “Beyond the Iran-Contra Affair Part 3: The World Anti-Communist League.” Anti-Imperialist U (July 19, 2016).

[18] Spence. “The Tsar’s Other Lieutenant,” p. 691.

[19] George Bodman, recommendation letter, FBI, File 100-15704, April 28, 1919; as cited in Richard Spence. “The Tsar’s Other Lieutenant,” Part 1, p. 209.

[20] MID, File 10110-920, Report #8, December 9, 1919; as cited in Richard Spence. “The Tsar’s Other Lieutenant,” Part 1, p. 209.

[21] Spence. “The Tsar’s Other Lieutenant,” Part I, p. 209.

[22] Kellogg. The Russian Roots of Nazism, p. 278-280.

[23] Rita T. Kronenbitter. “Paris Okhrana 1885-1905.” Center for the Study of Intelligence. Studies Archive Indexes. Vol. 10, No. 3. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol10no3/html/v10i3a06p_0001.htm

[24] John Curl. For All the People: Uncovering the hidden history of cooperation, cooperative movements, and communalism in America (PM Press, 2009), p. 144.

[25] M. I. Gaiduk. “Utiug,” materialy i fakty o zagotovitel'noi deiatel'nosti russkikh voennykh komissii v Amerike (New York, 1918), p. 10.

[26] Robert Singerman, “The American Career of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” American Jewish History, Vol. 71 (1981): 48-78.

[27] Ibid.

[28] “Letter from London.” The Japan Weekly Mail (November 20, 1889), p. 505; cited in Michael Hagemeister. “The American Connection: Leslie Fry and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” Kesarevo Kesarju: Scritti in onore di Cesare G. De Michelis (Firenze: Firenze University Press, 2014).

[29] G. Richards. The Hunt for the Czar (London, 1971) pp. 61-66, 195-210; cited in Michael Hagemeister. “The American Connection: Leslie Fry and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” Kesarevo Kesarju: Scritti in onore di Cesare G. De Michelis (Firenze: Firenze University Press, 2014).

[30] Michael Hagemeister. “The American Connection: Leslie Fry and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” Kesarevo Kesarju: Scritti in onore di Cesare G. De Michelis (Firenze: Firenze University Press, 2014).

[31] Victor E. Marsden. The Protocols of Zion, (The Book Tree: 1999), p. 242.

[32] Cesare G. De Michelis. The Non-Existent Manuscript, p. 115

[33] Ibid.

[34] “Pope Saint Pius X.” From the Housetops, No. 13, (Fall, 1976, St. Benedict Center, Richmond, New Hampshire).

[35] “History since 1798.” Sovereign Order of Saint John of Jerusalem. Retrieved from

http://www.theknightsofsaintjohn.com/History-After-Malta.htm

[36] Walter Ze’ev Laqueur. “Russia and Germany.” Transaction Publishers (January 1, 1965).

[37] “A Definitive List of Freemasons.” Freemasonry Matters (accessed July 30, 2017).

[38] Sharlet. The Family, p. 122.

[39] Norman Hapgood. “The Inside Story of Henry Ford's Jew-Mania.” Hearst’s International, Part V, (October 1922), pp. 39, 110.

[40] R. Singerman. “The American Career of the ‘Protocols of the Elders of Zion’.” American Jewish History LXXI, 1981-1982: 72; L.P. Ribuffo. “Henry Ford and ‘The International Jew’.” American Jewish History, LXIX, 1979-1980, p. 447.

[41] Hagemeister. “The American Connection.”

[42] Brasol hearing, 32, FBI, File 100-15704, cited in Richard Spence. “The Tsar’s Other Lieutenant: The Antisemitic Activities of Boris L’vovich Brasol, 1910-1960, Part II: White Russians, Nazis, and the Blue Lamoo.” Journal of Antisemitism (Vol 4 Issue #2 2012), p. 681.

[43] Scott Nehmer. Ford, General Motors, and the Nazis: Marxist Myths About Production, Patriotism, and Philosophies (Author House, 2013), p. 110.

[44] Victoria I. Zhuravleva. “Rethinking Russia in the United States during the First World War: Mr. Sigma’s American Voyage.” New Perspectives on Russian-American Relations, William Benton Wisehunt, Norman E. Saul, editors (Routledge, 2015).

[44] M. I. Gaiduk. “Utiug,” materialy i fakty o zagotovitel'noi deiatel'nosti russkikh voennykh komissii v Amerike (New York, 1918), p. 10.

[45] Kurt G. W. Luedecke. I Knew Hitler (New York: Scribner’s, 1938), p. 216; Spence. “The Tsar’s Other Lieutenant,” Part II, p. 700.

[46] James Pool. Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler’s Rise to Power, 1919-1933 (New York: Dial Press, 1978), p. 883.

[46] Kurt G. W. Luedecke. I Knew Hitler (New York: Scribner’s, 1938), p. 216; Spence. “The Tsar’s Other Lieutenant,” Part II, p. 700.

[47] Hagemeister. “The American Connection.”

[48] Nora Levin. The Holocaust: The Destruction of European Jewry 1933–1945.

[49] Kellogg. The Russian Roots of Nazism, p. 13.

[50] Ibid., p. 60.

[51] Ibid., p. 16.

[52] Ibid., p. 43.

[53] Ibid., p. 70.

[54] Wulf Schwarzwaller. The Unknown Hitler: His Private Life and Fortune (National Press Books, 1988), p. 80.

[55] Harald Strohm. Die Gnosis und der Nationalsozialismus (Suhrkamp, 1997), p. 57.

[56] Cited in Peter Robert Edwin Viereck. Metapolitics: From Wagner and the German Romantics to Hitler (Transaction Publishers, 2003), p. 229.

[57] Kellogg. The Russian Roots of Nazism, p. 70.

[58] Ibid., p. 60.

[59] Ibid., p. 279.

[60] Werner Maser. Der Sturm auf die Republik: Frühgeschichte der NSDAP (Dusseldorf: Econ Verlag, 1994), p.217.

[61] Konrad Heiden. Der Fuehrer: Hitler’s Rise to Power (New York: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1944), p. 184.

[62] Roger Manvell & Heinrich Fraenkel. Hess: A Biography (London: Drake Publishers, 1973), p. 22.

[63] Fritz von Siedler. Interview with Ernst Hanfstaengl (October 28, 1951).

[64] Joseph Howard Tyson. The Surreal Reich (iUniverse, 2010), p. 361.

[65] Joseph Howard Tyson. The Surreal Reich (iUniverse, 2010), p. 361.

[66] Gerda Walther. Zum anderen Ufer. Vom Marxismus und Atheismus zum Christentum (Reichl Verlag, St. Goar 1960), S. 473f., 591.

[67] Pascal Themanlys. “Le Mouvement Cosmique.” Retrieved from http://www.abpw.net/cosmique/theon/mouvem.htm

[68] Andreas Sommer. “Normalizing the Supernormal: The Formation of the “Gesellschaft Für Psychologische Forschung” (“Society for Psychological Research”), c. 1886–1890.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 2013 Jan; 49(1): 18–44.

[69] Susanne Meinl. Bodo Hechelhammer: Geheimobjekt Pullach (Berlin: Christoph Links Verlag, 2014), S. 55 ff.

[70] Adolf Hitler. Mein Kampf; Adolf Hitler. Table Talk.

[71] John Sedwick. “The Harvard Nazi.” Boston Magazine (May 15, 2006).

[72] Adolf Hitler. “XI: Nation and Race.” Mein Kampf, I, pp. 307–8.

[73] Adolf Hitler. Mein Kampf, vol. I, ch. X.

[74] Jeff Sharlet. The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power (HarperCollins, 2008), p. 123.

[75] “General Ludendorff Breaks with Hitler: Dinounces Him As Betrayer of German People and Associate of Freemasons.” Daily News Bulletin (Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Vol. XII, No. 90, May 2, 1931).

[76] Spence. Secret Agent 666, p. 194.

[77] “General Ludendorff Breaks with Hitler: Dinounces Him As Betrayer of German People and Associate of Freemasons.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency (May 2, 1931).

[78] Ricjard J. Evans. The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin, 2003), pp. 201-02.

[79] Andreas Sommer. “Policing epistemic deviance: Albert Von Schrenck-Notzing and Albert Moll(1).” Medical History, 56: 255–276.

[80] Corinna Treitel. A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern (Johns Hopkins, 2004), p. 219.

[81] Goodrick-Clarke. The Occult Roots of Nazism, p. 159.

[82] Corinna Treitel. A Science for the Soul: Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern (Johns Hopkins, 2004), p. 219.

Volume Three

Synarchy

Ariosophy

Zionism

Eugenics & Sexology

The Round Table

The League of Nations

avant-Garde

Black Gold

Secrets of Fatima

Polaires Brotherhood

Operation Trust

Aryan Christ

Aufbau

Brotherhood of Death

The Cliveden Set

Conservative Revolution

Eranos Conferences

Frankfurt School

Vichy Regime

Shangri-La

The Final Solution

Cold War

European Union