7. Avant-Garde

Salon de la Rose + Croix

As indicated by Roger Griffin, the noted scholar of fascism, while fascism has tended to be seen incorrectly as opposed to modernism, there was a significant interplay between the two. Many of the intellectual sources of modernism, Griffin points out, are not normally associated with the movement. The Futurists, Expressionists, Dadaists, Sorelians, and radical aesthetes from Van Gogh, Rilke, Stravinsky, D’Annunzio to Virginia Woolf, George Bernard Shaw, Wyndham Lewis, and Ernst Jünger, all shared with fascism a pessimism about the state of the modern world.[1] Instead, Griffin suggests that modernism must be expanded to embrace not just experimentalism in literature, art, and architecture, but to radical or revolutionary politics. The common denominator, Griffin explains, is:

…that in different ways the projects and movements in question aimed to put to an end to what Spengler portrayed as ‘the decline of the West,’ reverse what Max Weber called the ‘disenchantment’ of modern society, resolve what Sigmund Freud described as ‘the discontents’ of civilization, satisfy modern man’s (and woman’s) search for a ‘soul’ explored by Carl Jung, and remedy what Heidegger interpreted as a loss of ‘being at home in the world”.[2]

As Larry Shiner has demonstrated in The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, the notion of “art,” with its associated connotations, is a specifically Western invention. Western culture is the only civilization with a word for “art,” with all its connotations, where in other societies it is just craft. “The modern system of art,” explains Shiner, “is not an essence or a fate but something we have made. Art as we have generally understood it is a European invention barely two hundred years old.”[3] The conception of the word “Art” with a capital A, or Fine Art, has its origin in the Enlightenment, which attempted to redefine aristocratic pretensions for the new bourgeois classes. The notion of fine art was developed to distinguish “so-called polite and vulgar arts.” Shiner provides the example of music, which was played at home or for “religious and civic occasions” until it started to be played in concerts with no other goal than artistic enjoyment in and of itself: “On this high cultural ground, noble and bourgeois could meet as a fine art public, rejecting both the frivolous diversions of the rich and highborn as well as the vulgar amusements of the populace.”[4]

Effectively, Modern Art has become a new secular religion, or “a kind of metaphysical essence,” as Larry Shiner refers to it, where it would fill the spiritual void left from the abandonment of Christianity. Artists are the new monks and mystics, who explore the limits of human consciousness and the meaning of existence, and give it tangible form. So art has become abstracted from its original purpose. Essentially, avant-garde and modernist art was propaganda for nihilism, coordinated by the leading exponents of the occult underground. Modernism represents the sense of dissociation—or schizophrenia—that results from the nihilist proposition of the absence of meaning. Because it denies man’s inherent ability to recognize not only morality, but beauty itself, it deliberately opposes traditional esthetics. By producing the ugly and the disturbing, it derives prestige only through pretention, an elitism that suggests it can only be understood by the educated. It garners legitimacy by purporting to explore the human condition, and ennobles itself with a highly ambiguous term, calling itself “art.”

Mark Antliff, in Avant-Garde Fascism: The Mobilization of Myth, Art, and Culture in France, 1909–1939, investigated the central role that theories of the visual arts and creativity played in the development of fascism in France, and its formative influence on the history of avant-garde art. Between 1909 and 1939, a surprising number of modernists were implicated in this development, including such well-known figures as the symbolist painter Maurice Denis, the architects Le Corbusier and Auguste Perret, the sculptors Charles Despiau and Aristide Maillol, the “New Vision” photographer Germaine Krull, and the fauve Maurice Vlaminck. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s work also influenced the European Symbolists, a late nineteenth-century art movement of French, Russian and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts. In literature, the style had its beginnings with the publication Les Fleurs du mal (“The Flowers of Evil,” 1857) by Charles Baudelaire, which signaled the birth of modernism in literature.[5] Jean Moréas published the Symbolist Manifesto (“Le Symbolisme”) in Le Figaro on September 18, 1886, which names Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Paul Verlaine as the three leading poets of the movement.

Joséphin Péladan (1858 – 1918)

One of Symbolism’s most colorful promoters in Paris was art and literary critic Joséphin Péladan, who founded the Kabbalistic Order of the Rose-Cross (OKR+C) with Papus, Saint-Yves d’Alveydre and Stanislas de Guaita.[6] The “regency” of Fabré-Palaprat’s Order of the Temple, which was based on the spurious Larmenius Charter, was given by some surviving members to Péladan.[7] However, a schism resulted in the OKR+C due to Péladan’s eccentric behavior, having issued a public condemnation against a female member of the Rothschild banking dynasty.[8] In 1890–1891, Péladan abandoned the OKR+C, and established his own Ordre de la Rose-Croix catholique du Temple et du Graal (“Kabbalistic Catholic Rose-Croix Order of the Temple and the Grail”) which included many of the prominent Symbolist artists of the period. The reason for the split was that Péladan “refused to associate himself with spiritism, Freemasonry or Buddhism.”[9] Stanislas de Guaita, on the other hand, said that he didn’t want to turn the order into a salon for artists.[10]

Promotional poster for Josephin Péladan's Salon de la Rose + Croix.

Péladan saw the purpose of his Rosicrucian Order as fulfilling a religious purpose of encouraging the resurgence of the arts that were in decay:

Artist, you are a priest: Art is the great mystery and, if your effort results in a masterpiece, a ray of divinity will descend as on an altar. Artist, you are a king: Art is the true empire, if your hand draws a perfect line, the cherubim themselves will descend to revel in their reflection… They may one day close the Church, but [what about] the Museum? If Notre-Dame is profaned, the Louvre will officiate… Humanity, oh citizens, will always go to mass, when the priest will be Bach, Beethoven, Palestrina: one cannot make the sublime organ into an atheist! Brothers in all the arts, I am sounding a battle cry: let us form a holy militia for the salvation of idealism… we will build the Temple of Beauty… for the artist is a priest, a king, a mage, for art is a mystery, the only true empire, the great miracle.[12]

Péladan’s Salon de la Rose + Croix, which grew out the OKR+C, was a series of six avant-garde art, writing salons which he hosted in 1890s Paris.[13] Péladan wanted the Salon to create a forum for artists who rejected the officially approved academic art being exhibited by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and the influential Impressionists. Péladan learned from Wagner the idea that art could assume the functions of religion. The poster for the fifth salon in 1896, depicted Perseus holding the severed head of Émile Zola, in reference to the mythological story in which Perseus beheaded the Gorgon Medusa. “The artist is a priest, a king, a magus,” he proclaimed.[14] Central to Péladan’s doctrine was the promotion of the arts “especially of an esoteric flavour,” hoping to “overcome European materialism.”[15] The avant-garde Salon artists included many of the prominent Symbolist painters, writers, and music composers of the period. Writers as diverse as Paul Valéry, André Gide, André Breton, and Louis-Ferdinand Céline read Péladan with interest, as did Le Corbusier.[16]

Réne Guénon (1886 – 1951)

The idea of supra-rational knowledge, omnipresent in the work of Papus’ leading pupil, Réne Guénon (1886 – 1951), inspired avant-garde artistic circles who sought to go beyond rational thought, in particular the surrealist movement.[17] Guénon took on an “anti-Masonic” stance because he was opposed to the rationalist orientation of the fraternity, which became a constant feature of his career and strategy, which Marie-France James, one of the best Catholic critics of Guénon, described as a “clearly Gnostic-Masonic objective, with all the with all the hallmarks of a rehabilitation and propaganda operation.”[18] Guénon met Papus and was initiated into the Martinist Order in 1907, becoming “Superior Unknown.” He contributed to the occultist magazine Le Voile d’Isis founded by Papus in 1890. He was also initiated into the Rite of Memphis-Mizraim in 1907, and was raised to the third degree of Master Mason of Freemasonry. Guénon was also a close friend of Charles Barlet (a.k.a. Albert Faucheux), a member of the Max Theon’s Cosmic Movement, from whom he received numerous documents from his master, Saint-Yves d’Alveydre, and from the H.B.of L, for which he was the representative for France.[19]

In 1908, Guénon was secretary at the International Masonic Congress held in Paris organized by Papus, where he met Léonce Fabre des Essarts (1848 – 1917) who, under the pseudonym of Synésius, succeeded Jules Doinel as leader of the Gnostic Church, which was inspired by the ancient Gnostics and the Cathars, and which became the official church of the Martinist Order, as l'Église Gnostique Universelle (“Universal Gnostic Church”). Guénon joined the church, became a Gnostic bishop, and wrote many articles under the pseudonym Palingenius between 1909 and 1912 in the magazine La Gnose. With Victor Blanchard, a member of Papus’ Supreme Council, he also founded a short-lived Order of the Temple, which would later drive a wedge between him and Papus.[20]

Guénon was received in 1912 into the Thébah (“arch” in Hebrew) lodge, that was created in 1901 by Symbolists for the purpose of spiritual research, esotericism or the Kabbalah. Thébah belonged to the Grande Loge de France, which in 1894 became independent of the Supreme Council of France, once governed by Adolphe Crémieux, head of the Alliance Israelite Universelle. Crémieux and also Grand Master of the Rite of Mizraim. Its first Venerable Master, was Pierre Deulin (1973 – 1912), the brother-in-law of Papus. Deulin was also secretary of the Revue cosmique, organ of the Cosmic Movement created by Max Théon. The secretary of the OKR+C, Oswald Wirth (1860 – 1943), contributed to the rewriting of several high grades of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite with Albert Lantoine, at the request of the Grand Commander of the Supreme Council René Raymond, himself the founder of Thébah and a member of the Cosmic Movement.[21]

Guénon’s Traditionalism was developed from the notion, shared with the fascists, of the belief in the decadence of the modern world. Through the influence of Papus, Guénon insisted on the idea, already formulated before him by Joseph de Maistre and Fabre d’Olivet, of a primordial Tradition. By tradition, Guénon meant the Perennial Philosophy. This notion was the same as the Prisca Theologia, or “Ancient Wisdom,” of Renaissance philosopher Marisilio Ficino. In reality it was the Jewish Kabbalah, which Ficino considered to be a pure tradition imparted to the wise men of antiquity, and the key to establishing a universal religion that could reconcile Christian belief with ancient philosophy. It was also known to Blavatsky as “Ancient Wisdom” or “Wisdom-Religion.”

Reflecting the synarchist ideas of Saint-Yves, Guénon thought that the problem with modern society was that it was not ordered according to natural hierarchy, so that castes were assigned to their improper functions. To Guénon, democracy was an “inversion” because the lowest class, the Sudras, dominated over the priestly class, the Brahmins. Guénon believed that the West could be saved only through the revival of a spiritual elite, a kind of modern-day Rosicrucian Brotherhood, who understood the need for a return to a primordial Tradition, and would act as a governing secret society. “The true elite,” says Guénon in The Crisis in the Modern World, “would not have to intervene directly in these spheres [social and political], or take part in outward action; it would direct everything by an influence of which people were unaware, and which, the less visible it was, the more powerful it would be.”

Action Française

Charles Maurras (1868 – 1952) leader of the proto-fascist Action Française

Guénon, who would become an important intellectual inspiration to much of the political right, had been involved with Action Française and its founder Charles Maurras (1868 – 1952).[22] In the books Neither Right Nor Left and The Birth of Fascist Ideology, Zeev Sternhell claimed that Action Française influenced national syndicalism and, consequently, fascism. According to Sternhell, national syndicalism was formed by the combination between the integral nationalism of Action Française and the revolutionary syndicalism of Georges Sorel (1847 – 1922). The movement Action Française and the journal were founded by Maurice Pujo and Henri Vaugeois in 1899, as a nationalist reaction against the intervention of left-wing intellectuals on the Dreyfus Affair. Alfred Dreyfus (1859 – 1935) was a Jewish artillery officer whose trial and conviction in 1894 on charges of treason, known as the Dreyfus affair, became one of the most controversial and polarizing political dramas in modern French history and throughout Europe. It ultimately ended with Dreyfus’ complete exoneration.

Under Maurras Action française became a political movement that was monarchist, anti-parliamentarist, and counter-revolutionary and anti-Semitic. For Action française, the conspiratorial source of ills plaguing France were the Jews, Huguenots (French Protestants), or Freemasons. Maurras was also opposed to socialism, and after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, to communism. An agnostic influenced by Joseph de Maistre, Maurras’ advocacy of Catholicism was due to his belief that it was a factor of social cohesion and stability and to its importance in French history. Notwithstanding his religious unorthodoxy, Maurras gained a large following among French monarchists and Catholics, including the Orleanists, who supported the claim of the pretender to the French throne, the comte de Paris, Philippe (1869 – 1926), the great grandson of Louis Philippe I. Maurras agnosticism ultimately disturbed the Catholic hierarchy, and in 1926 Pope Pius XI placed some of his writings on the Index of Forbidden Books and condemned the Action Française philosophy as a whole.

Georges Sorel (1847 – 1922)

Also associated with Maurras and his Action Française was French revolutionary syndicalist Georges Sorel, one of the key activists who greatly influenced fascism. Heavily influenced by anarchism, Sorel contributed to the fusion of anarchism and syndicalism, into anarcho-syndicalism. Sorel promoted the legitimacy of political violence in Reflections on Violence (1908) and other works in which he advocated radical syndicalist action to achieve the revolutionary overthrow capitalism and the bourgeoisie through a general strike. In addition to Sorel, William James and Henri Bergson also heavily influenced the thought of Mussolini and the Italian fascists.[23] The Italian fascists put into practice Sorel’s belief in the need for a deliberately conceived “myth” to sway crowds into concerted action. Mussolini repeatedly acknowledged Sorel as his master: “What I am, I owe to Sorel.” And Sorel, in turn, called Mussolini “a man no less extraordinary than Lenin…” According to Mussolini:

Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945)

We have created our myth. The myth is a faith, it is passion. It is not necessary that it shall be a reality. It is a reality by the fact that it is a good, a hope, a faith, that it is courage. Our myth is the Nation, our myth is the greatness of the Nation! And to this myth, to this grandeur, that we wish to translate into a complete reality, we subordinate all the rest.[24]

Maurice Barrès (1862-1923)

Action Française also attracted figures like Maurice Barrès (1862 – 1923), one of the founding members of revived Martinist Order along with Papus. Barrès was also a friend since his youth of Stanislas de Guaita, and was interested in Asia, sufism and shi’ism. Known as the “Nietzsche of France,” Barrès advocated a quasi-spiritual “cult of myself,” which glorified a humanistic love of the self and he also dabbled in occult mysticisms in his youth. Barrès disseminated his ideas through political campaigns, French periodicals, and American journals like Scribners and the Atlantic.[25] Barrès rejected liberal democracy as a fraud, claiming that true democracy was authoritarian democracy. Barrès claimed that authoritarian democracy involved a spiritual connection between a leader of a nation and the nation’s people, and that true freedom did not arise from individual rights nor parliamentary restraints, but through “heroic leadership” and “national power.”[26]

Barrès was the first to coin the term “national socialism” in 1898, an idea which then quickly spread throughout Europe. With Barrès and Maurras, explains Sternhell, was found the first case of one of the essential components of fascism, tribal nationalism, based on social Darwinism. Barrès provided the French counterpart of the German Blut und Boden (“Blood and Soil”), abandoning the old theory, formed during the French Revolution, that society was a collection of individuals, in favour of the theory of the organic unity of the nation. According to Sternhell, Barrès “understood that a ‘national’ movement cannot be Marxist, liberal, proletarian, or bourgeois. Marxism and liberalism, he claimed, could never be anything other than movements of a civil war; a class war and a war of all against all in an individualistic society were merely two aspects of the same evil. As a result of this way of thinking at the end of the nineteenth century there appeared in France a new synthesis, the first form of fascism.”[27]

Futurism

Gabriele d’Annunzio (1863 – 1938)

Flag of the Regence of Carnaro, , also known as the Endeavor of Fiume

Barrès was a close associate of Gabriele d’Annunzio (1863 – 1938), who occupied a prominent place in Italian literature and later political life, often referred to under the epithets Il Vate (“the Poet”) or Il Profeta (“the Prophet”). One of D’Annunzio’s most important novels, scandalous in its day, is Il fuoco (“The Flame of Life”) of 1900, in which he portrays himself as the Nietzschean Superman Stelio Effrena, in a fictionalized version of his love affair with Eleonora Duse. He collaborated with composer Claude Debussy on a musical play Le martyre de Saint Sébastien (The Martyrdom of St Sebastian), 1911, written for Ida Rubinstein. The Vatican reacted by placing all of his works in the Index of Forbidden Books.

D’Annunzio was a Grand Master of the Scottish Rite Great Lodge of Italy which in 1908 had separated from the Grand Orient of Italy.[28] Subsequently, he was also initiated into the Ordine Martinista (“Martinist Order”) with the initiatory name “Ariel,” and he collaborated in Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia) with other 33rd degree Scottish Rite Freemasons and occultists like Alceste De Ambris, Sante Ceccherini and Marco Egidio Allegri. Allegri, a well-known figure in twentieth-century Freemasonry, joined both Freemasonry and Martinism at a very young age and at the age of twenty-six he was conferred with the 33º of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of the Grand Orient of Italy. Soon after, he became Grand Master of the Order of the Temple, and was appointed Patriarch Grand Conservator ad vitam of the Memphis Rite of Palermo, having already possessed a similar qualifications for the Misraïm Rite of Venice, rites that he unified into the Ancient and Primitive Oriental Rite of Mitzraïm and Memphis.[29]

Angered by the proposed handing over of the city of Fiume whose population was mostly Italian, at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, d’Annunzio led the seizure of the city and then declared Fiume an independent state, the Italian Regency of Carnaro. As the de facto dictator of Fiume, d’Annunzio maintained control over what has been described as a “new and dangerously potent politics of spectacle,” which was imitated by Mussolini.[30] D’Annunzio has been described as the John the Baptist of Italian fascism, as virtually the entire ritual of fascism was invented by him during his occupation of Fiume. This included the balcony address, the Roman salute, the cries of “Eia, eia, eia! Alala!” taken from the Achilles’ cry in the Iliad, as well as blackshirted followers (the Arditi).[31] The flag of the Regence of Carnaro, also known as the Endeavor of Fiume, featured the Ouroboros, the Gnostic symbol of a snake biting its own tail, and the seven stars of the Ursa Major.

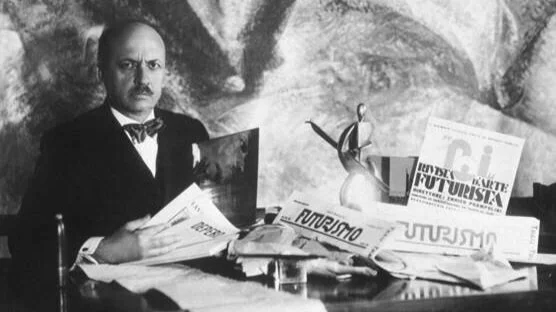

Filippo Marinetti (1876 – 1944)

On February 20, 1909, Marinetti’s most famous work, the Manifesto of Futurism was published in Le Figaro.

Mussolini’s concept of the New Man was inspired by Futurism, founded by Filippo Marinetti (1876 – 1944), who in 1916, linked with a former literary rival D’Annunzio, and together they had helped push Italy into war with the central powers. Marinetti was one of the most important connections between Sorel and the growing movement of Italian nationalists.[32] As well as Sorel, with whom Marinetti would remain in close contact, Futurism was also influenced by Charles Maurras and Maurice Barrès.[33] As indicated by Griffin, avant-garde modernism was not exclusively left-wing. Futurists, he explained, “saw Fascism as the embodiment of their vision of a new dynamic phase of civilization based on advanced technology.”[34]

Futurism advocated values such as instinct, strength, courage, sport, war, youth, dynamism and speed as exemplified by modern machines. One of the central features of the Futurist movement was the glorification of modernity, which he called “modernolatry,” based on the belief that technology had fundamentally improved the capacity of human beings. Futurism aimed to accomplish a comprehensive “revolution,” not only in different forms of art, such as literature, theatre and music, but also in politics, fashion, cuisine, mathematics, and in every possible aspect of life.[35]

On February 20, 1909, Marinetti spread his vision of a new art, politics and life across the front page of the French right-wing magazine Le Figaro, a publication which had been subsidized by Pyotr Rachkovsky, the head of the Okhrana in Paris, who had also employed H.P. Blavatsky, and who has been suspected of involvement in creating the Protocols of Zion.[36] “Let us give ourselves to the Unknown, not in desperation, but to replenish the deep wells of the Absurd!” he proclaimed in launching his Futurist Manifesto. Marinetti declared that “Art, in fact, can be nothing but violence, cruelty, and injustice.” For Marinetti, the war was “the most beautiful futurist poem that has seen the light of day.”[37]

Marinetti later became an active supporter of Benito Mussolini. Marinetti founded the Partito Politico Futurista (“Futurist Political Party”) in early 1918, which was absorbed into Mussolini’s Fasci Italiani di Combattimento in 1919, making Marinetti one of the first members of the National Fascist Party. Adapting Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch, Mussolini mandated that the New Man be brutal, barbarous, and abandon his romanticism. His conception of the New Futurist Man, building on previous futurist concepts, entailed: disdain of death and books, love of virility, violence, and war.[38]

New Age

Fabian Society member George Bernard Shaw (1856 – 1950)

The New Age editor and friend of Aleister Crowley, Alfred Richard Orage (1873 –1934)

Along with a number of prominent Fabians, Marinetti was a contributor to the magazine The New Age, which became one of the first places in England in which Freud’s ideas were discussed before World War I. The magazine’s editor, Alfred Richard Orage (1873 –1934), was a friend of Aleister Crowley, and also personally knew George Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead. In 1896, Orage married Jean Walker who was a passionate member of the Theosophical Society. Together they frequented the Northern Federation headquarters in Harrogate where Orage first met Annie Besant and other leading theosophists and began to lecture on mysticism and occultism in the Theosophical Review.[39] In 1900, he met Holbrook Jackson in a Leeds bookshop and lent him a copy of the Bhagavad-Gita. In return, Jackson lent him Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Orage conducted an in-depth study Nietzsche’s work, fusing the idea of Übermensch with mysticism, writing in Consciousness that “the main problem of the mystics of all ages has been the problem of how to develop the superconsciousness, of how to become supermen.”[40] Orage also worked with George Gurdjieff after he had been recommended to him by Gurdjieff’s leading student, P.D. Ouspensky.[41]

Gurdjieff’s leading student, P.D. Ouspensky (1878 – 1947)

Orage bought The New Age in 1907, in partnership with Jackson and with the support of George Bernard Shaw. Under the editorship of Alfred Richard Orage (1873 –1934), The New Age according to a Brown University press release, “helped to shape modernism in literature and the arts from 1907 to 1922.”[42] Between 1908 and 1914, The New Age was the premier little magazine in Britain, and was instrumental in pioneering the British avant-garde. The circle of The New Age contributors was highly close-knit and widely influential, and included Aleister Crowley, Ananda Coomaraswamy, Havelock Ellis, H.G. Wells, Florence Farr, George Bernard Shaw, Marmaduke Pikthall, C.H. Douglas, Hilaire Belloc and Ezra Pound. Although many contributors were Fabians, Orage distanced himself from their politics and sought to represent a wide range of political views. Orage declared himself a socialist and followed Georges Sorel in arguing that trade unions should pursue improved working conditions.[43]

Marinetti’s influence resulted in the short-lived literary magazine called Blast, founded by New Age contributor Wyndham Lewis, which is considered emblematic of the modern art movement in England, and is recognized as a seminal text of pre-World War I modernism.[44] Lewis was an English painter and author, and friend of American poet Ezra Pound, a major figure of the early modernist movement, whose poetry was featured in Blast. Pound, a close friend of Yeats, helped discover and shape the work of contemporaries such as T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Robert Frost and Ernest Hemingway. He became friendly with Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, Fernand Léger and others of the Dada and Surrealist movements, as well as Basil Bunting, Hemingway and his wife Hadley. Outraged by the brutality of the World War I, Pound lost faith in England, and moved to Italy in 1924 where, throughout the 1930s and 1940s, he embraced Mussolini’s fascism, and expressed support for Hitler.

Ezra Pound (1885 – 1972)

Dimitrije Mitrinović (1887 – 1953)

One of the most important contributors to Orage’s New Age was Bosnian-Serb mystic Dimitrije Mitrinovic (1887 – 1953), who while at Munich University, was linked with Wassily Kandinsky. As a young man Mitrinovic was active in the Young Bosnia movement, inspired by the various Young movements founded by Mazzini. The group, which opposed the Austro-Hungarian empire, sought the assistance of the Serbian government and received assistance by the Black Hand, a covert organization founded by the Serbian Army, and which had ties to Freemasonry. Ostensibly in retaliation against Austria’s 1908 annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which the Serbs had claimed for themselves, the Black Hand was responsible for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 which precipitated World War I.

Mitrinovic believed that only Europe and the Aryan race could “establish a functional world system in which each of the races and nations is called upon to play its natural and organic part.”[45] Despite the anti-Semitic overtones of his theories, Mitrinovic placed particular attention on the role played by the nation of the Jews, which “was ‘chosen’ for the ‘mission’ of becoming White… in preparation for their role as the inheritors or ruling race of the kingdom of the world.”[46] Towards his aims, Mitrinovic maintained correspondence with Henri Bergson, H.G. Wells, Maxim Gorky, Maurice Maeterlinck, Pablo Picasso, Filippo Marinetti, Anatole France, George Bernard Shaw, and Knut Hamsun.

Martin Buber (1878 – 1965)

Mitrinovic also approached a number of potential Jewish contributors, including composer Arnold Schoenberg, Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem and Zionist and existentialist Martin Buber (1878 – 1965), a relative of Karl Marx.[47] Buber was a direct descendant of the sixteenth-century rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen, known as the Maharam of Padua. Karl Marx is another notable relative. However, Buber broke with Judaism. He maintained close friendships to Zionists and philosophers such as Chaim Weizmann, Max Brod, Hugo Bergman, and Felix Weltsch. In 1898, he joined the Zionist movement, and in 1902 became the editor of its central organ, the weekly Die Welt. In that year, he published his thesis, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Individuationsproblems, on Jakob Boehme and Nicholas of Cusa. Buber also wrote Tales of the Hasidim, based on the written and oral lore of the founder of Hasidism, Baal Shem Tov. Buber also wrote The Origin and Meaning of Hasidism, contrasting Hasidism with biblical prophecy, Spinoza, Freud, Sankara, Meister Eckhart, Gnosticism, Christianity, Zionism, and Zen Buddhism.

Psychologist Alfred Adler, who had been assisted by Aleister Crowley

As George Mosse and Paul Mendes-Flohr have argued, völkisch themes can easily be identified in Buber’s ideology.[48] According to Avraham Shapira, “At the time Buber’s thought was assuming its distinctive shape, the spiritual concerns and intellectual currents on which he drew were inextricably bound up with European romanticism and with its German version in particular.”[49] For Buber, race, not religion, was the true unifying of the Jews. The “primeval peculiarity” (Uralte Eigenart) of the Jew was conceived by Buber as being embodied in “the distinct and unique power of his blood.”[50] For Buber, Zionist sentiment is aroused when the individual becomes conscious of “what confluence of blood has produced him, what rounds of begettings and births has called him forth.”[51] The individual can then come to the conclusion that “blood is a deep-rooted nurturing force,… that the deepest layers of our being are determined by blood,” which in turn allows him to leave his inauthentic society and look for “the deeper-reaching community of those whose substance he shares.”[52]

Mitrinovic founded the Adler’s Society (the English Branch of the International Society for Individual Psychology), with Hungarian-born Jew, Alfred Adler, the founder of the school of individual psychology. Adler had also been assisted in his work with his patients by Aleister Crowley.[53] In collaboration with Freud and a small group of Freud’s colleagues, Adler was among the co-founders of the psychoanalytic movement and a core member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. To Freud, Adler was “the only personality there.”[54] Adler is considered, along with Freud and Jung, to be one of the three founding figures of depth psychology, which emphasizes the unconscious and psychodynamics, and thus to be one of the three great psychologist/philosophers of the twentieth century.

Modernism

Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in the Atelier at 27 Rue de Fleurus. Photograph by Man Ray in 1923.

Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso

Through the association Marinetti with the Symbolists, Futurism prepared the ground for the modernist revolution of the early twentieth century. The Cubism of Picasso and Braque, along with the abstract art of Wassily Kandinsky, German Expressionism and the Futurist movement of Marinetti, are considered to be a hallmark of modernism. More than any other person, it was Gertrude Stein, who coordinated the avant-garde art movement. A close friend of Bertrand Russell, Stein started her career under the tutelage of William James at Harvard University.[55] With James’ supervision, Stein and another student, Leon Mendez Solomons, performed experiments on normal motor automatism, a phenomenon hypothesized to occur in subjects when their attention is divided between two simultaneous activities such as writing and speaking. These experiments produced examples of writing that appeared to represent “stream of consciousness,” a psychological theory often attributed to James and the style of modernist authors Virginia Woolf and James Joyce.[56] The case is similar to what is known as automatic writing or psychography, a claimed psychic ability to produce written words without consciously writing from a subconscious, spiritual or supernatural source.

In her Paris salon, Stein entertained nightly a circle frequented by the painters Picasso, Matisse, Georges Braque, Diego Rivera, the American writers Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, the composers Maurice Ravel, Stravinsky, Erik Satie and many, many others. At their Paris residence, Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo had essentially inaugurated, the first museum of modern art. Their private collection, assembled from 1904 to 1913, soon had a worldwide reputation. Their acquisitions started with buying Gauguin’s Sunflowers and Three Tahitians, Cézanne’s Bathers and two Renoirs. In the first half of 1905 the Steins acquired Cézanne’s Portrait of Mme Cézanne and Delacroix’s Perseus and Andromeda. Shortly after the opening of the Salon d’Automne of 1905, the Steins acquired Matisse’s Woman with a Hat and Picasso’s Young Girl with Basket of Flowers. By early 1906, Leo and Gertrude Stein's studio had many paintings by Henri Manguin, Pierre Bonnard, Pablo Picasso, Paul Cézanne, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Honoré Daumier, Henri Matisse, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Wassily Kandinsky’s Yellow, Red, Blue (1925)

Igor Stravinsky (1882 – 1971)

It was from these circles that the “primitivist” movement was born, that became the hallmark of the new avant-garde movement in painting, music, and literature during the first two decades of this century. Representative of this movement were the cubist portraits of Picasso, the pagan-themed ballet Rite of Spring, and the automatic writing of Stein’s novella Melanctha. The pagan-themed ballet Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky, a close friend to Aldous Huxley and W.H. Auden, has been heralded as the birth of modernism.[57] As suggested by its subtitle “Pictures of Pagan Russia,” the theme for Stravinsky’s opera is the pagan worship of the dying-god, whose resurrection was traditionally celebrated on Easter. In the opera, Stravinsky dared to associate the rite with human sacrifice. When the ballet was first performed at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees in 1913, the controversial nature of the music and choreography caused a riot in the audience. The concept for the controversial ballet the Rite of Spring was developed by his friend Nicholas Roerich, another important member of the Theosophical Society and also a friend of H. G. Wells.

Many in these circles were connected with the Theosophical Society and intersected with the Golden Dawn, which included, among others, Yeats, Maude Gonne, Constance Lloyd (the wife of Oscar Wilde), Arthur Edward Waite and Bram Stoker, author of Dracula. Shaw’s mistress, Florence Farr, had been a member of the Golden Dawn, as well as a friend of Masonic scholar Arthur Edward Waite. These personalities were often also members of, or further intersected with, the Theosophical Society, which included D.H. Lawrence, as well as William Butler Yeats, Lewis Carroll, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Jack London, E.M. Forster, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Henry Miller, Kurt Vonnegut, Dame Jane Goodall, Thomas Edison, Piet Mondrian, Paul Gauguin, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Gustav Mahler. “I got everything from the ‘Secret Doctrine’ (Blavatsky),” Mondrian wrote, in 1918.[58]

Monte Verità (literally Hill of Truth) in Ascona, Switzerland.

Mary Wigman (1886 – 1973)

Martin Buber, along with Frieda and D.H. Lawrence, Franz Kafka, and Alma Mahler, the wife of composer and Theosophical Society member Gustav Mahler, were members of the sexual cult of Dr. Otto Gross [59] Gross was the dominant influence at the Bohemian enclave of Monte Verità in Ascona, Switzerland—originally a resort area for members of Helena Blavatsky’s Theosophy cult—which attracted Hermann Hesse, Carl Jung, Isadora Duncan, Paul Klee, Rudolf Steiner, Max Weber. Ascona became a sort of early New Age haven of bohemianism and the occult, featuring experimentation in surrealism, modern dance, Dada, paganism, feminism, pacifism, nudism, psychoanalysis and natural healing. Between 1900 and 1920, the community and the settlement of projects around it was home for shorter or longer periods to a large number of famous people, ranging from artists and writers, such as Paul Klee and Herman Hesse and to well-known anarchists, such as Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin. There were Dadaists and dancers such as Isadora Duncan, and psychologists and theosophists, including Rudolf Steiner. Even Lenin and Trotsky were visitors at one time.[60]

The OTO had its only female lodge at Ascona. In 1916, Reuss moved to Basel, Switzerland where he established an “Anational Grand Lodge and Mystic Temple” of the OTO and the Hermetic Brotherhood of Light at Monte Verità. In 1917, Reuss organized the Sun Festival (“Sonnenfest”), a conference there covering many themes, including societies without nationalism, women’s rights, mystic freemasonry, and dance as art, ritual and religion. Performing at the festival was Mary Wigman (1886 – 1973) was a German dancer and choreographer considered one of the most important figures in the history of modern dance.[61] Wigman was a student of Carl Jung, OTO member Rudolf von Laban (1879 – 1958), known as the “Founding Father of the Expressionist Dance” in Germany.[62] In 1934, Laban was promoted to director of the Deutsche Tanzbühne, in Nazi Germany. He directed major festivals of dance under the funding of Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry from 1934-1936. Laban wrote during this time that “we want to dedicate our means of expression and the articulation of our power to the service of the great tasks of our Volk. With unswerving clarity our Führer points the way.”[63]

Dada

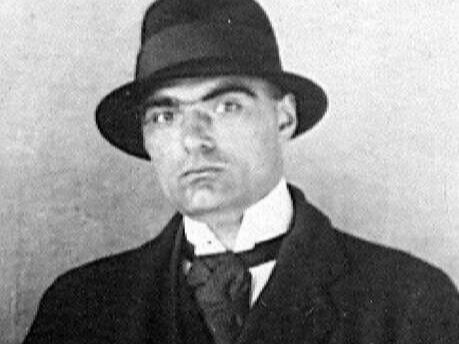

The Cabaret Voltaire on Spiegelgasse 1 in Zurich (circa 1930)

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917)

Monte Verità was significant for the development of both the Cabaret Voltaire and the European avant-garde known as Dada.[64] Paradoxically, modern art has its origins in the anti-art agenda of Dada, a movement which ultimately influenced later styles and groups including surrealism, Situationism, pop art and Fluxus. Dada rejected reason and logic, celebrating nonsense, irrationality and intuition. Dada, which was itself was influenced by Futurism, and which also had political affinities with the radical left, was a protest against the bourgeois nationalist and colonialist interests, and against the cultural and intellectual conformity in art as well as society, which Dadaists believed were the root cause of the war. Dada therefore concentrated its anti-war politics through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works.

Probably the most famous work of the period was Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, a porcelain urinal, signed “R.Mutt,” which caused a scandal when it was submitted for the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York in 1917, but was rejected by the committee, after much discussion about whether the piece was art or was not. Duchamp’s Fountain is now regarded by some art historians and theorists of the avant-garde as a major landmark in twentieth century art. Duchamp therefore later complained, “The fact that they are regarded with the same reverence as objects of art probably means that I have failed to solve the problem of trying to do away entirely with art.”[65]

Hugo Ball performing at Cabaret Voltaire (1916)

Dada was begun by a group of artists and poets associated with the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich. Living across the street from the Cabaret Voltaire were Lenin, Karl Radek and Gregory Zinoviev who were busy planning the Bolshevik Revolution.[66] Though the cabaret was to be the birthplace of the Dada movement, it featured artists from every sector of the avant-garde, including Futurism's Marinetti, and radically experimental artists, many of whom went on to have a profound influence, including Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Giorgio de Chirico, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Max Ernst. On July 28, 1916, Hugo Ball read out the Dada Manifesto, and also published a journal with the same name, which featured work from Guillaume Apollinaire and had a cover designed by Taeuber-Arp.

Tristan Tzara (1896 – 1963), born Samuel or Samy Rosenstock, was best known for being one of the founders and central figures of the movement. Dada grew out of an already vibrant artistic tradition in Eastern Europe, particularly Romania, that was transported to Switzerland when a group of Jewish modernist artists—Tristan Tzara, Marcel and Iuliu Janco, Arthur Segal, and others—settled in Zurich. According to Menachem Wecker, the works of the Jewish Dadaists represented “not only the aesthetic responses of individuals opposed to the absurdity of war and fascism” but, invoking the well-worn light unto the nations theme, insists that they brought a “particularly Jewish perspective to the insistence on justice and what is now called tikkun olam.”[67]

In recent years, researchers such as Tom Sandqvist, Milly Heyd, Haim Finkelstein, and Marius Hentea, have given new emphasis on the Jewishness of the Romanian contributors to Dada.[68] In his book Dada East: The Romanians of Cabaret Voltaire, Tom Sandqvist points out that Tzara’s Hasidic and Kabbalistic influences of his youth were evident in his art.[69] Tzara’s hometown Moinesti is, in Andrei Codrescu’s opinion, “the center of the modern world, not only because of Tristan Tzara’s invention of Dada, but because its Jews were among the first Zionists, and Moinesti itself was the starting point of a famous exodus of its people on foot from here to the land of dreams, E’retz-Israel.”[70]

Dada artists, Paris (1920). From left to right, Back row: Louis Aragon, Theodore Fraenkel, Paul Eluard, Clément Pansaers, Emmanuel Fay (cut off). Second row: Paul Dermée, Philippe Soupault, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes. Front row: Tristan Tzara (with monocle), Celine Arnauld, Francis Picabia, André Breton.

Norman Finkelstein links Tzara’s Dada to the influence of the Sabbateans’ and Frankists’ notion of “redemption through sin.”[71] According to the Jewish American poet Jerome Rothenberg, there are “definite historical linkages between the transgressions of messianism and the transgressions of the avant-garde.”[72] Rothenberg refers to these heresies as “libertarian movements,” and connects them to Jewish receptivity to the forces of secularization and modernity, leading in turn to the “critical role of Jews and ex-Jews in revolutionary politics (Marx, Trotsky etc.) and avant-garde poetics (Tzara, Kafka, Stein etc.).”[73] Milly Heyd endorses Rothenberg’s thesis, observing that “Tzara uses terminology that is part and parcel of Judaic thinking and yet subjects these very concepts to his nihilistic attack.”[74] Tzara declared that, “Dada is using all its strength to establish the idiotic everywhere. Doing it deliberately. And is constantly tending towards idiocy itself… The new artist protests; he no longer paints (this is only a symbolic and illusory reproduction).”[75]

Surrealism

The Persistence of Memory by Dali (1931)

Andre Breton (1896 –1966)

Salvador Dali (1904 – 1989) and Man Ray (1890 – 1976)

An article by Jean-Pierre Lassalle entitled “André Breton et la Franc-Maçonnerie” revealed to the public the existence of a core of active Freemasons from the Thébah lodge who were tied the Parisian surrealists.[76] René Guénon’s work had an impact on many artists, in particular in the surrealist movement that developed out of the Dada activities during World War I. One example was André Breton (1896 –1966), who was interested in the works of Joseph Péladan.[77] As a result of his campaigning, Tzara created a list of so-called “Dada presidents,” who represented various regions of Europe. According to Hans Richter, it included, alongside Tzara himself, figures ranging from Max Ernst, André Breton, Julius Evola and Igor Stravinsky.[78] Breton was the leader of the Surrealist movement, and was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was, above all, a revolutionary movement.[79] The surrealists also looked to the Marxist dialectic and the work of such Frankfurt School exponents as Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse. According to Walter Benjamin, “Since Bakunin, Europe has lacked a radical concept of freedom. The Surrealists have one.”[80] From the 1920s onward, the surrealist movement spread around the globe, eventually affecting the visual arts, literature, film and music of many countries and languages, as well as political thought and practice, philosophy, and social theory.

All the French poets admired by the surrealists, such as Hugo, Nerval, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Lautramont, Mallarme, Jarry and Apollinaire, and the utopian socialists as well, can be linked to the occultism of Swedenborg and Eliphas Lévi. [81] Breton as well was profoundly influenced by Levi who wrote, “imagination applied to reason is genius.” For Breton all art, even the most realistic, has its origin in magic. But art which is specifically magical is that which represents the triumph of the mind over outer reality.[82] As a way of tapping into the “irrational,” the Surrealists began experimenting with automatic writing, or automatism, a sort of stream of consciousness effort, and published the writings, as well as accounts of dreams. As indicated by Nadia Choucha in Surrealism and the Occult: Shamanism, Magic, Alchemy, and the Birth of an Artistic Movement, “The technique of automatism, borrowed both from the psychological technique of free association and from spiritualist medium, was considered to be the best way of releasing creativity and inspiration.”[83] The group led by André Breton claimed that automatism was a better tactic for societal change than those of Dada, as led by Tzara, who was now among their rivals. Breton’s group grew to include writers and artists from various media such as Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, and Dada artist Man Ray, who was born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia to Russian Jewish immigrants.

Jean Cocteau (1889 – 1963), purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion

A very important exponent of the avant-garde was French surrealist artist Jean Cocteau (1889 – 1963). In his early twenties, Cocteau had become associated with Action francaise and with the writers Ernst Jünger, Marcel Proust, André Gide, and Maurice Barrès. It was during his time with Action Française that Cocteau made his acquaintance of his close friend, Jacques Maritain (1882 – 1973).[84] Jacques Maritain’s grandfather was Jules Favre, a Freemason and a friend of Victor Hugo, the author of Les Miserables and The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.[85] In 1904, Maritain married Raïssa Oumançoff, a Russian Jewish émigré. They underwent a spiritual crisis which was resolved when they attended the lectures of Henri Bergson at the Collège de France. Bergson’s critique of scientism dissolved their intellectual despair and instilled in them “the sense of the absolute.”[86] They then converted to the Roman Catholic faith in 1906. Maritain also discussed mystical theology in his famous work The Degrees of Knowledge, drawing on Aquinas, and the Marian mystics and Marranos, St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross.[87]

Jacques Maritain (1882 – 1973) and his wife Raïssa Oumançoff

Maritain was a friend and supporter of René Guénon, with whom he corresponded frequently on philosophy and metaphysics.[88] Guénon hoped to convince Maritain and the Catholic Church to revitalize Christianity through a dialogue with oriental religions and he envisaged a restoration of traditional “intellectualité” in the West on the basis of Roman Catholicism and Freemasonry.[89] Maritain abandoned Action Française in 1926 when it was condemned by the Catholic Church for its nationalistic and anti-democratic tendencies.[90] Maritain began to develop the principles of a liberal Christian humanism and defense of natural rights. At the height of his fame, in the 1920s and 30s, Maritain lectured at Oxford, Yale, Notre Dame, and Chicago. He also taught at Paris, Princeton, and Toronto. By the early 1930s, Maritain was an established figure in Catholic thought, and gained an international reputation as an outspoken anti-fascist and opponent of anti-Semitism.[91]

In addition to Cocteau, Maritain also counted among his friends the artist, Marc Chagall. When he and Maritain met, Cocteau had recently lost his companion Raymond Radiguet and had plunged into opium addiction. Maritain supported Cocteau throughout his recovery. Under Maritain’s influence, Cocteau made a temporary return to the sacraments of the Catholic Church. Cocteau again returned to the Church later in life and undertook a number of religious art projects. Cocteau also met the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, artists Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani, and numerous other writers and artists with whom he later collaborated. He wrote the libretto for Stravinsky’s opera-oratorio Oedipus rex. Cocteau became closely associated with the Dada movement. He collaborated on the Anthologie Dada and participated in a Dada matinée in 1920, along with Breton, Tzara, Francis Picabia and Max Jacob. His friend Max Jacob (1876 –1944) was a lifelong friend of Picasso. Jacob introduced him to Guillaume Apollinaire, who in turn introduced Picasso to Georges Braque. Jacob, who was Jewish, claimed to have had a vision of Christ in 1909, and converted to Catholicism, hopeful that this conversion would alleviate his homosexual tendencies.[92] Jacob would become close friends with Jean Cocteau, Jean Hugo, Christopher Wood and Amedeo Modigliani, who painted his portrait in 1916. Jean Hugo was the great-grandson of author Victor Hugo. Cocteau behaved like a Dada “pervert,” producing phallic images and cartoons for Picabia. Although for this reason Cocteau would become known briefly as an “anti-Tzara,” Cocteau and Tzara posed together for a photographic artwork by Man Ray in 1922.[93]

[1] Roger Griffin. “Fascism’s Modernist Revolution: A New Paradigm for the Study of Right-wing Dictatorships.” Fascism 5 (2016) p. 112.

[2] Ibid., p. 110.

[3] Larry Shiner. The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001) p. 3.

[4] Ibid., p. 97.

[5] Clement Greenberg. “Modernism and Postmodernism.” William Dobell Memorial Lecture, Sydney, Australia, Oct 31, 1979. Arts 54, No.6 (February 1980).

[6] Marcel Roggemans. History of Martinism and the F.U.D.O.S.I (Lulu.com, 2009), p. 36.

[7] Massimo Introvigne. “Ordeal by Fire: The Tragedy of the Solar Temple.” In The Order of the Solar Temple: The Temple of Death (ed.) James R. Lewis (Ashgate, 2006), p. 22.

[8] Kerry Bolton. “Joséphin Péladan & the Occult War Against Liberal Decadence.”

[9] Tobias Churton. Gnostic Philosophy: From Ancient Persia to Modern Times (Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions, 2005). p. 322.

[10] André Billy (1971). Stanislas de Guaita (in French). p. 37.

[11] Marcel Roggemans. History of Martinism and the F.U.D.O.S.I. Translated by Bogaard, Milko (Morrisville, North Carolina: Lulu Press, 2009). p. 36.

[12] Péladan. Catalogue du Salon de la Rose + Croix (Paris: Galerie Durand-Ruel, 1892), pp. 7-11, cited by Sasha Chaitow, “Making the Invisible Visible: Péladan’s Vision of Ensouled Art” (August 6, 2015).

[13] André Billy (1971). Stanislas de Guaita (in French). p. 37.

[14] Ibid.

[15] John Michael Greer. The New Encyclopedia of the Occult (Llewellyn Worldwide, 2003). p. 365.

[16] Alex Ross. “The Occult Roots of Modernism.” The New Yorker (June 26, 2017).

[17] Xavier Accart. René Guénon ou le renversement des clartés : Influence d'un métaphysicien sur la vie littéraire et intellectuelle française (1920-1970) (Paris, Archè EDIDIT, 2005), p. 118.

[18] Marie-France James. Ésotérisme et christianisme autour de René Guénon (Paris, N.E.L., 1981), p. 129; cited in Christian Lagrave. Les dangers de la gnose contemporaine (Le Sel, 2012), p. 100.

[19] René Guénon, “F.-Ch. Barlet et les sociétés initiatiques,” Le Voile d'Isis, April 1925; Jean-Pierre Laurant. “Barlet, François-Charles.” Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism (Brill, 2006), p. 163.

[20] Christian Lagrave. Les dangers de la gnose contemporaine (Le Sel, 2012), p. 100.

[21] Jean Louis Turbet. “Mouvement Cosmique et Rite Ecossais Ancien et Accepté.” (November 1, 2021). Retrieved from https://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/index2.php?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.jlturbet.net%2F2021%2F10%2Fmouvement-cosmique-et-rite-ecossais-ancien-et-accepte.html#federation=archive.wikiwix.com&tab=url

[22] “The Spiritual Fascism of Réne Guénon and His Followers,” Retrieved from http://www.naturesrights.com/knowledge power book/Guénon.asp

[23] Jonah Goldberg. Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, From Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning (Doubleday, 2008) p. 423 n. 21.

[24] Herman Finer. Mussolini’s Italy (1935), p. 218; cited in Franklin Le Van Baumer, (ed.), Main Currents of Western Thought (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), p. 748.

[25] Alexander Reid Ross. Against the Fascist Creep (AK Press, 2017).

[26] Robert Soucy “Barres and Fascism,” French Historical Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Spring, 1967), pp. 67-97; Duke University Press. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/285867. pp. 87-90.

[27] Zeev Sternhell. The Birth of the Fascist Ideology (Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 11.

[28] Fulvio Conti. Storia della massoneria italiana. Dal Risorgimento al fascism (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2003).

[29] “Marco Egidio Allegri.” The Three Luminaries (December22, 2020). Retrieved from https://www.threeluminaries.com/2020/12/marco-egidio-allegri/

[30] Brian Lowe. Moral Claims in the Age of Spectacles: Shaping the Social Imaginary (Springer, 2017). p. 72.

[31] H. Stuart Hughes. The United States and Italy (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1953), pp. 76 and 81–82.

[32] Gigliola Gori. “Model of masculinity: Mussolini, the ‘new Italian’ of the Fascist era. International Journal of the History of Sport, 4 (1999), pp. 27-61.

[33] Alexander Reid Ross. Against the Fascist Creep (AK Press, 2017).

[34] Roger Griffin. “Fascism’s Modernist Revolution: A New Paradigm for the Study of Right-wing Dictatorships.” Fascism, 5, 2 (2016). Retrieved from https://brill.com/view/journals/fasc/5/2/article-p105_2.xml?language=en

[35] Marja Härmänmaa. “Marinetti, Machine, and Superman: Or About the Destructiveness of Technology.” The 13th International Conference of the International Society for the Study of European Ideas, in cooperation with the University of Cyprus.

[36] Catherine Evtuhov & Stephen Kotkin. The Cultural Gradient: The Transmission of Ideas in Europe, 1789-1991 (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002), p. 140.

[37] Robert Fox. “Back to futurism?” The Guardian (February 20, 2009).

[38] Gori. “Model of masculinity.”

[39] Tom Steele. Alfred Orage and the Leeds Art Club 1893-1923 (The Orage Press, 1990), pp. 33–34.

[40] Roger Luckhurst. The Invention of Telepathy (1870–1901) (Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 257.

[41] Peter Washington. Madame Blavatsky’s baboon: a history of the mystics, mediums, and misfits who brought spiritualism to America (Schocken Books, 1995) p. 170.

[42] “Modernist Journals Project Has Grant to Digitize Rare Magazines.” Brown University press release (April 19, 2007)

[43] Charles Ferrall. Modernist Writing and Reactionary Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2001), p. 16.

[44] Alison Flood. “Lewis comes back into favour, and print” The Guardian (August 19, 2008).

[45] Andrew Rigby. Initiation and Initiative: An Exploration of the Life and Ideas of Dimitrij Mitrinovic (Boulder: East European Monographs, 1984) p. 80.

[46] Ibid., p. 78.

[47] Neil Rosenstein. The Unbroken Chain: Biographical Sketches and Genealogy of Illustrious Jewish Families from the 15th–20th Century (revised ed.), (New York: CIS, 1990)

[48] Maor. “Moderation from Right to Left: The Hidden Roots of Brit Shalom,” p. 85.

[49] Avraham Shapira. “Buber’s Attachment to Herder and to German Volkism.” Studies in Zionism, 14, no. 1 (1993), p. 9.

[50] Martin Buber. “Wege zum Zionismus,” (1901), Die Jüdische Bewegung, vol. 1, Berlin, 1916, p. 42.

[51] Cited in Zeev Sternhell. The Founding Myths of Zionism (Princeton University Press, 1998), p. 85.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Crowley to Schneider October 5, 1944 GJY Collection, cited in Richard Kaczynski. Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley (North Atlantic Book, 2010) p. 448.

[54] Freud, cited in Ernest Jones. The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud (1964), p. 353.

[55] Peter Wyer, “The Racist Roots of Jazz.”

[56] Steven Meyer. Irresistible Dictation: Gertrude Stein and the Correlations of Writing and Science (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001).

[57] Katherine O’Callaghan. Essays on Music and Language in Modernist Literature: Musical Modernism (Routledge, 2018).

[58] Alex Ross. “The Occult Roots of Modernism.” The New Yorker (June 26, 2017).

[59] Michael Minnicino. “The Frankfurt School and ‘Political Correctness’,” (Fidelio, Winter 1992).

[60] William McGuire. Bollingen: An Adventure in Collecting the Past (Princeton University Press, 1989), p. 22.

[61] Susan Manning. Ecstasy and the Demon: The Dances of Mary Wigman (University of Minnesota Press, 2006), p. 73.

[62] Evelyn Dörr. Rudolf Laban: The Dancer of the Crystal (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2008), pp. 99-101

[63] Rudolf Laban, “Meister und Werk in der Tanzkunst,” Deutsche Tanzzeitschrift (May 1936), cited in Horst Koegler, “Vom Ausdruckstanz zum ‘Bewegungschor’ des deutschen Volkes: Rudolf von Laban,” in Intellektuellen im Bann des National Sozialismus, ed. Karl Corino (Hamburg: Hoffmann & Campe, 1980), p. 176.

[64] Christine Eggenberg, “Sublime truth, exalted art.” Self-Organization of Cogniion and Applications to Psychology (Ascona: October 25–28, 2000). Retrieved from https://www.embodiment.ch/research/symposien/HA9.html

[65] Marcel Duchamp, “I Propose to Strain the Laws of Physics.” ARTnews 34 (December, 1968), p. 62.

[66] Menachem Wecker. “Eight Jewish Dada Artists.” The Jewish Press (August 30, 2006).

[67] Ibid..

[68] Alfred Brodenheimer. “Dada Judaism: The Avant-Garde in First World War Zurich.” Jewish Aspects in Avant-Garde: Between Rebellion and Revelation, edited by Mark H. Gelber, Sami Sjöberg (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2017), p. 26.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Andrei Codrescu. The Posthuman Dada Guide: Tzara and Lenin Play Chess (Princeton University Press, 2009).

[71] Norman Finkelstein. Not One of Them in Place and Jewish American Identity (SUNY Series in Modern Jewish Literature and Culture, State University of New York Press, New York, 2001), p. 100.

[72] Ibid.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Milly Heyd. “Tristan Tzara/Shmuel Rosenstock: The Hidden/Overt Jewish Agenda,” in Washton-Long, Baigel & Heyd (Eds.) Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Anti-Semitism, Assimilation, Affirmation (Brandeis University Press, 2010). p. 213.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Jean-Pierre Lassalle. “André Breton et la Franc-Maçonnerie” Histoires littéraires, 1 (January 2000).

[77] Alex Ross. “The Occult Roots of Modernism.” The New Yorker (June 26, 2017).

[78] Hans Richter. Dada. Art and Anti-art (Thames & Hudson, London & New York, 2004), p. 201

[79] Eddy Batache. “René Guénon et le surréalisme,” Cahier de l'Herne on René Guénon, p. 379.

[80] Steven M. Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within: Comparative Perspectives on “Redemption Through Sin.” The Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy, Vol. 6, 1997, p. 40.

[81] Clifford Browder. André Breton: Arbiter of Surrealism. (Librairie Droz, 1967), p. 136.

[82] Idid. p. 141.

[83] Nadia Choucha. Surrealism and the Occult: Shamanism, Magic, Alchemy, and the Birth of an Artistic Movement (Inner Traditions / Bear & Co, 1992) p. 52.

[84] Richard Francis Crane. “Surviving Maurras: Jacques Maritain’s Jewish Question.” Patterns of Prejudice (Vol. 42 , Iss. 4-5, 2008).

[85] Richard D. E. Burton. Holy Tears, Holy Blood: Women, Catholicism, and the Culture of Suffering in France, 1840-1970 (Cornell University Press, 2004), p. 77.

[85] Ibid., p. 22.

[86] Martha Hanna. The Mobilization of Intellect: French Scholars and Writers During the Great War (Harvard University Press, 1996), p. 39.

[87] Robert A. Delfina. “Mystical Theology in Aquinas and Maritain.” Douglas A. Ollivant ed., Jacques Maritain and the Many Ways of Knowing (American Maritain Association, 2002), p. 254.

[88] Robin Waterfield. René Guénon and the Future of the West: The Life and Writings of a 20th-Century Metaphysician (Hillsdale, NY: Sophia Perennis, 2002) p. 36.

[89] Cf. among others his Aperçus sur l'ésotérisme chrétien (Éditions Traditionnelles, Paris, 1954) and Études sur la Franc-maçonnerie et le Compagnonnage (2 vols, Éditions Traditionnelles, Paris, 1964–65) which include many of his articles for the Catholic journal Regnabit.

[90] William Sweet. “Jacques Maritain,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2013 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

[91] Richard Francis Crane. “Surviving Maurras: Jacques Maritain’s Jewish Question.” Patterns of Prejudice (Vol. 42 , Iss. 4-5, 2008).

[92] “Max Jacob.” Poetry Foundation (March 21, 2020). Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/max-jacob

[93] James S. Williams. Jean Cocteau (London: Reaktion, 2008), p. 78.

Volume Three

Synarchy

Ariosophy

Zionism

Eugenics & Sexology

The Round Table

The League of Nations

avant-Garde

Black Gold

Secrets of Fatima

Polaires Brotherhood

Operation Trust

Aryan Christ

Aufbau

Brotherhood of Death

The Cliveden Set

Conservative Revolution

Eranos Conferences

Frankfurt School

Vichy Regime

Shangri-La

The Final Solution

Cold War

European Union