20. Kings of Jerusalem

Double-headed eagle

Relevant Genealogies

Eleonora of Toledo, the wife of Cosimo I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1519 – 1574), great-grandson of Cosimo the Elder and a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, was brought up in Naples at the household of Jacob Abarbanel’s son Don Samuel Abarbanel and daughter-in-law Benvenida.[1] Their children would intermarry with the important houses of Este, Sforza and Savoy, who were hereditary claimants of the Kingdom of Jerusalem—producing several Grand Masters of the so-called Priory of Sion, popularized in Dan Brown’s sensationalistic The Da Vinci Code. According to the genealogical research of Ian Mladjov, through two trajectories—from Agatha of Bulgaria through the Plantagenets, and from the Palaiologos dynasty of Montferrat who ruled the Byzantine Empire and employed the heraldic symbol of the double-headed eagle—the House of Savoy can trance their descent to the Bagratuni dynasty of Armenia who claimed Jewish descent.[2]

The double-headed eagle or double-eagle is an ancient motif that appears in Mycenaean Greece and in the Ancient Near East, especially in Hittite iconography. One of the earliest examples is Anzû, a lesser divinity or monster in several Mesopotamian religions, depicted as a lion-headed eagle with wings outspread, grasping a lion in each talon. Anzu was an important influence for the figure of Tiamat, the Mesopotamian sea-serpent or dragon defeated by Marduk, or Bel, a crucial and decisive event in the Babylonian epic of creation, Enuma elish. Like the Baal Epic, the Tiamat myth is one of the earliest recorded versions of the Chaoskampf, the battle between a culture hero and a chthonic or aquatic serpent or dragon, which later evolved into the legend of Saint George and the dragon.[3]

The eagle has been the coat of arms of the ancient Arsacid, Mamikonyan, and Bagratuni dynasties of Armenia. The use of double-headed eagle or double-eagle dates back to Mycenaean Greece and in the Ancient Near East, especially in Hittite iconography. In the eleventh and thirteenth century, representations have also been found in Islamic Spain, France and the Serbian principality of Raška. From the thirteenth century onward, it became even more widespread, and was used in the Islamic world by the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum and the Mamluk Sultanate. By about the tenth century, the double-headed eagle appears in Byzantine art, but as an imperial emblem only much later, during the final century of the Palaiologos dynasty.

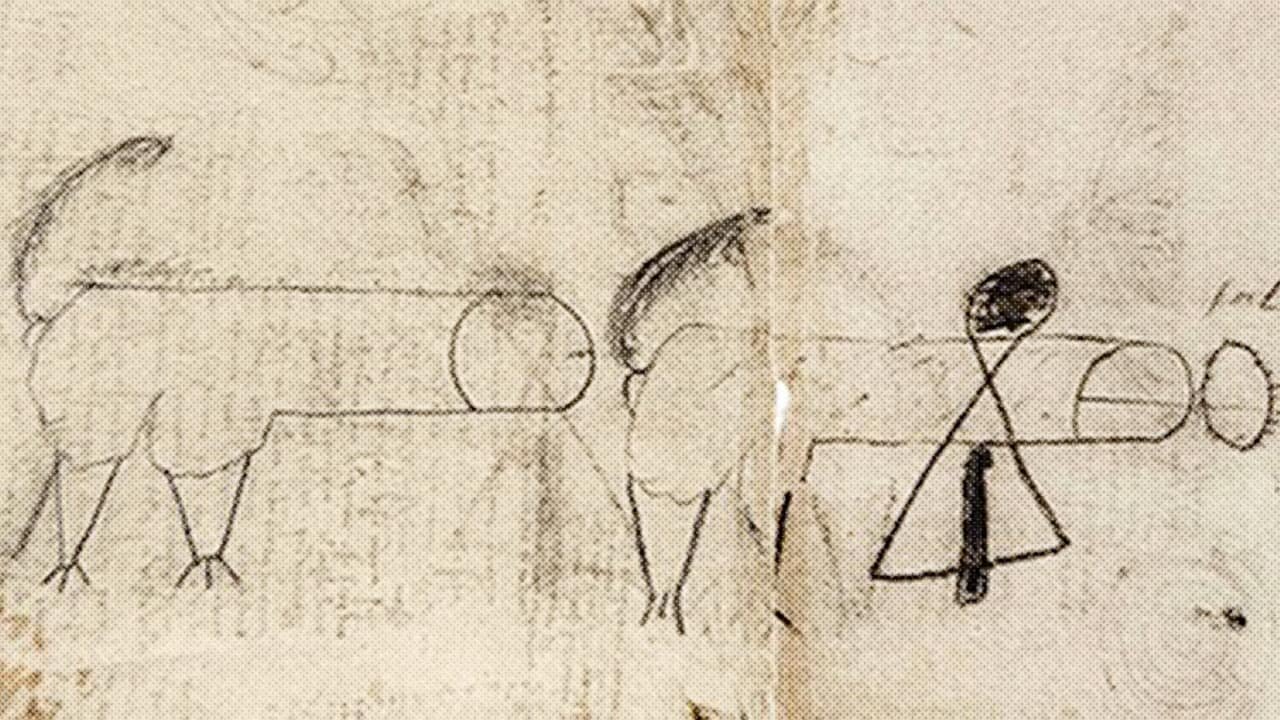

Miniature of Hungarian chieftain Ügyek, the father of Almos, displaying the Turul hawk on his shield, from the Illuminated Manuscript

The Seljuk, like the Hungarians, were descended from Turks, from whom they inherited the mythological symbol of the Turul hawk. According to Hungarian legends, Emese, the mother of Almos, the father of Arpad, the founder of the Hungarian nation, was impregnated by the Turul hawk in a dream. Simon of the Gesta, who wrote the Hunnorum et Hungarorum in the late thirteenth century, identified the hawk by the Turkic word turul and then called Árpád “of the Turul kindred.” According to the Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle of the fourteenth century, “On his shield, Attila used to carry a coat of arms, in the likeness of a hawk86 with crowned head. So long as they governed themselves as a community, until the times of the Duke Géza, son of Taksony [grandson of Arpad], all the Hungarians in the army carried this sign.”[4]

The German Imperial Eagle, or Reichsadler, is believed to have been used by Charlemagne, derived ultimately from the Aquila or eagle standard, of the Roman army. Frederick Barbarossa popularized the use of the eagle as the Imperial emblem by using it in all his banners, coats of arms, coins and insignia. Judith of Bavaria, the mother of Frederick Barbarossa, was the granddaughter of Magnus Billung, Duke of Saxony, and Sophia of Hungary, the daughter of Bela I of Hungary and Richeza of Poland, the granddaughter of Boleslav the Brave, the son of Dobrawa of Bohemia and Mieszko I of Poland, whose father was Boleslav I the Cruel, who acted as the conduit for the Schechter Letter of Hasdai ibn Saprut to King Joseph of the Khazars. An early depiction of a double-headed eagle in a heraldic shield, attributed to Frederick Barbarossa’s grandson, Emperor Frederick II, is found in the Chronica Majora by Matthew Paris (c. 1200 – 1259). After he was crowned Emperor in 1433, Emperor Sigismund, who was also King of Hungary, used a black double-headed eagle, which like the Gnostic Ouroboros serpent biting its tale employed for the emblem of his Order of the Dragon, is a common alchemical symbol. From that time, the single-headed Reichsadler represented the title of King of the Romans, and the double-headed version, inherited from the Palaiologos dynasty, the title of Holy Roman Emperor.[5]

Anzu, an important influence for the figure of Tiamat, the Mesopotamian sea-serpent or dragon defeated by Marduk, or Bel, a crucial and decisive event in the Babylonian epic of creation, Enuma elish.

The House of Savoy, like the houses of Gonzaga, Cleves, Lorraine, Wettin and Montferrat all began their ascent after they were recognized by Emperor Sigismund, founder of the Order of Dragon. The House of Savoy, whose descendants would inherit the title of King of Jerusalem, was a royal dynasty established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region, which comprises roughly the territory of the Western Alps between Lake Geneva in the north and Dauphiné in the south. The house descended from Humbert I (1003 –1047 or 1048) whose son, Otto of Savoy (c. 1023 – c. 1057/1060), succeeded to the title of count in 1051 after the death of his elder brother Amadeus I of Savoy. Through his marriage to Adelaide, heiress of the march of Susa and county of Turin, Otto obtained extensive possessions in northern Italy, and thereafter, the House of Savoy concentrated its expansion efforts towards Italy. The House of Savoy’s lands occupied much of modern Savoy and Piedmont.

Otto’s daughter Bertha married Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, and their daughter Agnes married Frederick I, Duke of Swabia, the first ruler of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, and was the grandmother of Frederick Barbarossa. Otto was succeeded by his son, Amadeus II of Savoy (c. 1050 – 1080), whose son Humbert II (1065 – 1103) married William I of Burgundy. Humbert II’s daughter Adélaide of Maurienne who married Louis VI of France, and their son Louis VII of France married Eleanor of Aquitaine, to father Marie of France, wife of Henry I of Champagne and sponsor of Grail author Chretien de Troyes. Humbert II was succeeded by Amadeus III, Count of Savoy (1095 – 1148), whose daughter Matilda married Afonso I of Portugal. Amadeus III’s son and successor was Humbert III, Count of Savoy (1136 – 1189, father of Thomas I of Savoy (1178 – 1233).

Conquest of the Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, by the crusaders in 1204

Thomas was succeeded by his son Amadeus IV of Savoy (1197 – 1253), who married Margaret of Burgundy, whose daughter Beatrice of Savoy married Manfred, King of Sicily, son of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, the grandson of Frederick Barbarossa. Frederick II’s other royal title was King of Jerusalem by virtue of his marriage to Isabella II of Jerusalem, the daughter of Conrad of Montferrat (d. 1192) and Isabella I of Jerusalem, who was descended from Baldwin II of Jerusalem and Morphia of Armenia of the Skull of Sidon legend. The Marquises and Dukes of Montferrat were the rulers of a territory in Piedmont south of the Po and east of Turin called Montferrat. The area was constituted as the marca Aleramica (“March of Montferrat”) by Berengar II of Italy in 950, for his son-in-law Alermo (d. 991), during a redistribution of power in the northwest of his kingdom. When Italy came under the direct control of the Holy Roman Empire in 962, Aleramo’s titles were confirmed by the Otto the Great.

Aleram's descendants were relatively obscure until Rainier, Marquis of Montferrat (c. 1084 – May 1135) in the early twelfth century. About 1133, Rainier’s son Marquess William V (c. 1115 – 1191) married Judith of Babenberg, Leopold III of Austria and Agnes of Waiblingen. Agnes’ first husband was Frederick I, Duke of Swabia, grandfather of Frederick Barbarossa. As the half-sister of Conrad III of Germany, William V’s marriage to Judith greatly increasing the family’s prestige. William V entered into the Italian policies of Conrad and the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos, setting a Ghibelline precedent for his successors, and with his sons became involved in the Crusades.

William V was the father of Conrad of Montferrat. Conrad’s brother was Boniface I, Marquis of Montferrat (c. 1150 – 1207), leader of the Fourth Crusade (1201–04). Though the intent of the Fourth Crusade had been to recapture the city of Jerusalem from the Muslims, a sequence of events culminated in the Crusader army’s Sack of Constantinople, the capital Byzantine Empire, in 1204. Boniface was assumed to be the new emperor, but the Venetians vetoed him and chose Baldwin of Flanders (1172 – c. 1205) instead, who became Baldwin I, the first emperor of the Latin Empire of Constantinople. Boniface I established the Kingdom of Thessalonica in the Latin Empire of Greece.

Guy of Lusignan lost his claim to the throne of Jerusalem when his wife Sibylla died in 1190. Conrad then acquired the title by virtue of his marriage to her half-sister Isabella. The marriage was conducted by Philip of Dreux, Bishop of Beauvais, son of Conrad's cousin Robert I of Dreux, brother of Louis VII of France. However, in 1192, Conrad was killed by the Assassins. Under torture, the surviving Assassin claimed that Richard the Lionheart had ordered the killing. Isabella later married Richard’s nephew, Henry II of Champagne, the son of Henry I of Champagne and Marie of France, and then Guy of Lusignan’s brother Aimery of Lusignan. After Isabella died in 1205, her and Conrad’s daughter Maria became Queen of Jerusalem, while her stepbrother from Aimery’s first marriage to Eschiva of Ibelin became Hugh I of Cyprus (1194/1195 – 1218) and married Maria’s half-sister, Alice of Champagne. Maria married John of Brienne (c. 1170 – 1237), a leader of the Fifth Crusade, an attack against Jerusalem with Andrew II of Hungary and Duke Leopold VI of Austria. In 1225, Jon gave their daughter in marriage Isabella II Frederick II, who ended John's rule over the Kingdom of Jerusalem. In 1231, John was crowned as co-ruler with Baldwin II 1217 – 1273) of the Latin Empire in Constantinople.

Manfred and Beatrice’s daughter Constance of Sicily married Peter III of Aragon, the son of James I of Aragon, who was raised by the Templars, after his father Peter II of Aragon was killed at the Battle Muret supporting the Cathars. Peter III’s sister Violant was married to Alfonso X of Castile, known as el Astrologo. Peter III and Constance’s children included James II of Aragon, founder of the Order of Montesa; Elizabeth, the wife of Denis I of Portugal, founder of the Ordr of Christ, and Frederick III of Sicily, who hired the services of the famous Templar Roger de Flor. Frederick III married Eleanor of Anjou, sister of Charles I of Hungary, founder of the Order of Saint George. Their daughter Constance of Sicily, married Henry II of Lusignan, who transferred property of Templars to Hospitallers. After the end of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1291 with the conquest of Saladin, Henry II continued to use the title of King of Jerusalem, and after his death, the title was claimed by his successors, the kings of Cyprus.

Amadeus IV of Savoy’s sister Beatrice married Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Provence, who was raised by the Templars with his cousin James I of Aragon. Beatrice and Ramon had four daughters, including Margaret of Provence, wife of Louis IX of France, great-grandson of Louis VII of France and Adela of Champagne, daughter of Theobald IV of Champagne; Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III of England, who was involved in blood libel case of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln, and was the father of Edward I of England, grandfather of Edward III, founder of the Order of the Garter; Sanchia of Provence, the wife of Richard of Cornwall, son of John, King of England; and Beatrice of Provence, wife of Charles I of Anjou, founder of the Angevin kings of Naples, who used the title of King of Jerusalem.

Kingdom of Naples

Charles I of Anjou defeats his opponent, Manfred, King of Sicily, at the Battle of Benevento (1266).

After the end of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1291 with the conquest of Saladin, Henry II continued to use the title of King of Jerusalem, and after his death, the title was claimed by his successors, the kings of Cyprus. Amadeus IV of Savoy’s sister Beatrice married Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Provence, who was raised by the Templars with his cousin James I of Aragon. Beatrice and Ramon had four daughters, including Margaret of Provence, wife of Louis IX of France, great-grandson of Louis VII of France and Adela of Champagne, daughter of Theobald IV of Champagne; Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III of England, who was involved in blood libel case of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln, and was the father of Edward I of England, grandfather of Edward III, founder of the Order of the Garter; Sanchia of Provence, the wife of Richard of Cornwall, son of John, King of England; and Beatrice of Provence, wife of Charles I of Anjou, founder of the Angevin kings of Naples, who used the title of King of Jerusalem.

Genealogy of the House of Lusignan

Hugh VIII of Lusignan + Burgundia of Rancon

Aimery of Cyprus + Isabella I of Jerusalem

Melisende de Lusignan + Bohemond IV of Antioce

Marie of Antioch (sold title of King of Jerusalem to Charles I of Anjou)

Aimery of Cyprus + Eschiva of Ibelin

Hugh I of Cyprus + Alice of Champagne

Isabelle de Lusignan + Henry of Antioch

Hugh III of Cyprus + Isabella of Ibelin

Henry II of Lusignan + Constance of Sicily (d. of Frederick III of Sicily)

Amalric of Lusignan + Isabella of Armenia (d. of Leo II)

Guy of Lusignan

John of Lusignan + Soldane Bagrationi of Georgia

Leo V (last Latin king of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia) + Marguerite de Soissons

Mary + James II of Aragon

Guy, Constable of Cyprus + Eschiva of Ibelin

Hugh IV of Cyprus + Alix of Ibelin

John of Lusignan

James I of Cyprus, + Helvis of Brunswick-Grubenhagen

Janus of Cyprus + Charlotte of Bourbon

John II of Cyprus + Helena Palaiologina

Charlotte, Queen of Cyprus + Louis of Cyprus

ANNE OF LUSIGNAN + LOUIS, DUKE OF SAVOY (s. of Amadeus VIII, Duke of Savoy, Elevated Duke of Savoy by Sigismund of Luxembourg, founder of the Order of the Dragon + Mary of Burgundy, d. of Jean de Berry, b. of Marie of Valois, and Philip the Bold, grandfather of Philip the Good, founder of the Order of the Golden Fleece)

In 1277, Charles I of Anjou bought a claim to the throne of Jerusalem from Mary of Antioch, by proximity of blood to Conradin (1252 – 1268), who had crowned himself King of Jerusalem as the grandson of Frederick II and his third wife, Isabella of England. Mary was the granddaughter of Amalric II of Jerusalem and Isabella I of Jerusalem. Conradin was executed in 1268 by Charles I of Anjou, who had seized Conradin’s kingdom of Sicily by papal authority. At the time of his death, Marie of Antioch was the only living grandchild of Isabella I, and claimed the throne of Jerusalem on the basis of proximity in blood to the kings of Jerusalem. The Haute Cour of Jerusalem passed over her claim, however, and instead chose Hugh III of Lusignan, a great-grandson of Isabella I, as the next ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Following the rebellion in 1282, Charles I of Anjou was forced to leave the island of Sicily by Peter III of Aragon's troops. Charles, however, maintained his possessions on the mainland, customarily known as the “Kingdom of Naples,” after its capital city. Charles and his Angevin successors maintained a claim to Sicily, warring against the Aragonese until 1373, when Joanna I of Naples, the great-granddaughter of Charles II, formally renounced the claim by the Treaty of Villeneuve. Joanna’s reign was contested by Louis I of Hungary (1326 – 1382), the son of Charles I of Hungary, who captured the kingdom several times (1348–1352). Joanna I also played a part in the ultimate demise of the first Kingdom of Naples. As she was childless, she adopted Louis I, Duke of Anjou (1339 – 1384), as her heir. Louis was the brother of John, Duke of Berry, Philip the Bold and Marie of Valois. His father John II of France appointed him Duke of Anjou in 1360.

Charles II and his Angevin successors maintained a claim to Sicily, warring against the Aragonese until 1373, when Joanna I of Naples, the great-granddaughter of Charles II, formally renounced the claim by the Treaty of Villeneuve. Joanna was the last of the 106 biographies of women featured Boccaccio’s in his De Mulieribus Claris ("Concerning Famous Women”), where she is described as “Joanna, queen of Sicily and Jerusalem, is more renowned than other woman of her time for lineage, power, and character.” Boccaccio affirmed that Joanna I was a descendant of a noble bloodline, claiming that it could be traced all the way back to “Dardanus, the founder of Troy, whose father the ancients said was Jupiter.” Joanna’s reign was contested by Louis I of Hungary (1326 – 1382), the son of Charles I of Hungary, who captured the kingdom several times (1348–1352). Joanna I also played a part in the ultimate demise of the first Kingdom of Naples. As she was childless, she adopted Louis I, Duke of Anjou (1339 – 1384), as her heir. Louis was the brother of John, Duke of Berry, Philip the Bold and Marie of Valois. His father John II of France appointed him Duke of Anjou in 1360.

Rene of Anjou, or Good King René, founder of the Order of the Crescent, the Order of the Fleur de Lys, and purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion

Joan I’s claim was in spite of the claims of her cousin, the Prince of Durazzo, effectively setting up a junior Angevin line in competition with the senior line. This led to Joan I's murder in 1382 at the hands of the Prince of Durazzo (1345 – 1386), grandson of Charles II, and his seizing the throne as Charles III of Naples. The two competing Angevin lines contested each other for the possession of the Kingdom of Naples over the following decades. In 1389, Louis II of Anjou (1377 – 1417), son of Louis I, managed to seize the throne from Ladislas of Naples’ son of Charles III, but was expelled by Ladislas in 1399. Charles III's daughter Joanna II adopted Alfonso V of Aragon (1396 – 1458) and Louis III of Anjou as heirs alternately, finally settling succession on Louis’ brother René of Anjou who succeeded her in 1435.

Sigismund of Luxembourg, Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Order of the Dragon

In 1430, when Louis I of Bar, the last Duke of Bar of the male line died, Bar passed to his great-nephew, René of Anjou, Count of Piedmont, Duke of Bar, Duke of Lorraine, King of Naples, titular King of Jerusalem and Aragon, and purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion. René was the great-grandson of Marie of Valois and Robert I, Duke of Bar, the grandson of Edward I, Count of Bar, a purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion. It was at the request of her brother Jean Duke Berry that Jean d’Arras wrote a long prose romance called the Roman de Mélusine or the Chronique de Melusine part of Le Noble Hystoire de Lusignan. D’Arras dedicated the work to Marie of Valois, and expressed the hope that it would aid in the political education of her children. René married to Isabella, Duchess of Lorraine, and in 1434, he was recognized as Duke of Lorraine by Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg, founder of the Order of the Dragon.

Alfonso V of Aragon (1396 – 1458), member or the Order of the Dragon and Order of the Golden Fleece

In 1441, Naples was also claimed by Alfonso V of Aragon, also a member of the Order of the Dragon, who had been first adopted and then repudiated by Joanna II, when he laid a six-month siege to Naples. René of Anjou returned to France in the same year, and though he retained the title of King of Naples his effective rule was never recovered [7] Alfonso V was the son of Ferdinand I of Aragon (1380 – 1416), who was the founder of the Order of the Jar. According to legend, the Order of the Jar was one of the oldest military orders in Europe, having been founded in the Kingdom of Navarre in the eleventh century. In the most elaborate version of the legend, the order was founded by García III in 1043. When he was hunting with his falcon, which was chasing a pigeon, both birds stood at the entrance to a cave in Nájera, inside of which was an image of the Virgin Mary next to a jar of lilies, symbol of the Annunciation. García decided to build a monastery near the cave, which became Santa María la Real of Nájera, and at the same time create the Orden de la Terraza, an archaic word for jar.[8] After Ferdinand took over the Crown of Aragon, the Order of the Jar effectively became the royal order of his kingdoms, including Aragon, Sicily and Naples after 1443. In 1415, Ferdinand I conferred membership into the order on Emperor Sigismund. He also conferred membership on the ambassadors of King Ladislas of Naples. Alfonso V of Aragon introduced the order to the Kingdom of Naples after he conquered it in 1443. Alfonso V conferred the order on Philip the Good after the latter arranged for his election to the Order of the Golden Fleece.[9]

Philip the Good, founded Order of the Golden Fleece to celebrate his marriage to Isabella of Portugal, sister of Henry the Navigator, Grand Master of the Order of Christ.

René of Anjou’s sister Marie married Charles VII of France, the son of Charles VI. Charles VII supported René’s claim to Lorraine by right of his wife Isabella, elder daughter of Charles II of Lorraine, but it was contested by Antony of Vaudémont (c. 1400 – 1458). Antony defeated René at Bulgnéville in 1431, took him prisoner, and handed him over to Philip the Good. Released on parole the following year after giving his sons John and Louis as hostages, in 1433 René agreed that his elder daughter Yolande de Bar should marry Antony’s son Ferry II of Vaudémont (c. 1428 – 1470). Yolande is also said to have succeeded her father as Grand Master of the Priory of Sion. In the nineteenth century, a romanticized version of Yolande’s early life was popularized by King René’s Daughter, a play by Henrik Hertz, which was later adapted to Tchaikovsky’s opera Iolanta.

But, in 1434, when the Sigismund recognized René as Duke of Lorraine, and when René had also inherited Anjou and Provence from Louis III, Philip the Good summoned René back into captivity. René finally obtained his discharge in 1437, promising a heavy ransom and making territorial concessions. Peace between René and Philip finally came about when René’s eldest son Jean of Calabria married Marie of Bourbon, daughter of Charles, duke of Bourbon and Philip’s niece in 1444.

The centre of the roundel depicts a shield bearing the arms of René of Anjou. Quarterly of five, three in chief and two base, they are (from top left to bottom right) Kingdom of Hungary (Ancient), Anjou-Naples, Kingdom of Jerusalem, Duchy of Anjou and Duchy of Bar. Over-all is superimposed the escutcheon in pretence for the Kingdom of Aragon. Above the shield is a crowned helmet surmounted with the crest of a double fleur-de-lys between a pair of dragon's wings. Behind the helmet and shield is a mantle decorated with the arms of Anjou. Above the crest the letters IR in tree-trunk capitals refer to René's christian name and that of his second wife, Jeanne de Laval. Below the shield is the insignia of René's own chivalric Order of the Crescent ('Croissant'), a collar enscribed OS:EN:CROISSANT:.

Cosimo de' Medici (1389 – 1464), Italian banker and politician who established the Medici family as effective rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance.

As a result of the marriage of his daughter Margaret of Anjou to Henry VI, René pressured Margaret into persuading her husband to give up Maine and the English claims to Anjou which Henry agreed to, Maine was eventually won back militarily in 1448. It was during that year René founded the neo-Arthurian Military Order of the Crescent, aimed at a level of prestige comparable to that of the Order of the Golden Fleece. The avowed purpose of the Order was the re-establishment of the Judaic-Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem. René himself described the Order of the Crescent as a revived version of the old Order of the Ship and the Double Crescent, created by Louis IX for nobles who accompanied him on the ill-fated Sixth Crusade, commonly known as the Crusade of Frederick II (1228–1229), a military expedition to recapture the city of Jerusalem. The Sovereign of the Order was in theory the Reigning King of Jerusalem of the Anjou dynasty.[10] Early members of the order included René’s son-in-law Ferry and the elder Cosimo de Medici. Cosimo’s interest in ancient manuscripts, which gave birth to his academy of Platonic studies in Florence headed by Marsilio Ficino, was through the encouragement of René of Anjou, who also fostered the transplantation of Italian Renaissance thought in his own dominions.[11]

After a brief interlude of 1453–1473, when the duchy of Lorraine passed in right of Marie to Jean, Lorraine reverted to the House of Vaudemont, in the person of Yolande’s son, René II, Duke of Lorraine (1451 – 1508), who was Count of Vaudémont, Duke of Lorraine, Duke of Bar, and claimed the crown of the Kingdom of Naples and the County of Provence as the Duke of Calabria, and as King of Naples and Jerusalem.

House of Savoy

Amadeus VIII (1383 – 1451) was elevated by his first cousin Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, founder of the Order of the Dragon, to the Duke of Savoy in 1416.

The double-headed eagle device of the Palaiologos dynasty of Byzantine emperors.

In 1396, when the title and privileges of the final king of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, Leo V (1342 – 1393), were transferred to his cousin James I (1334 – 1398) of the Lusignan dynasty, the title of King of Armenia was thus united with the titles of King of Cyprus and King of Jerusalem. James’ daughter Mary of Lusignan married Ladislaus of Naples, while his son and successor, Janus of Lusignan (1375 – 1432), married Charlotte de Bourbon. Janus was succeeded by John II of Cyprus (1418 – 1458), who married Helena Palaiologina, a member of the Palaiologos dynasty, and titular Queen of Armenia and Jerusalem. The Palaiologos dynasty, who used the double-headed eagle as their emblem, came from a direct line of descent back to Comuta Nikola (d. 1014), founder of the dynasty who ruled the First Bulgarian Empire, and who had married Ripsime or Hripsime, possibly a daughter of King Ashot II of Armenia of the Bagratuni dynasty of Armenia who claimed Jewish descent. Nikola was also the great-grandfather of Agatha of Bulgaria, from whom descend the kings of Scotland and the House of Plantagenet.[12]

The dynasty began in 1261, with Michael VIII Palaiologos (1223 – 1282), recaptured Constantinople from the Crusaders in 1261. The double-headed eagle symbolized the dynasty's interests in both East and West. The double-headed eagle was taken back to Western Europe by two daughters of the Baldwin I and Marie of Champagne, sister of Henry II, Count of Champagne. Margaret II, Countess of Flanders, struck coins in Flanders with the eagle. Her sister Joan, Countess of Flanders, married Thomas II of Savoy (c. 1199 – 1259), bringing the eagle in the Savoy achievement.[13] It is thought that Thomas II’s father, Thomas I of Savoy, adopted for his coat of arms the black single-headed eagle with scarlet claws and beak in 1207 at Basel, where he espoused the cause of the Hohenstaufens.[14] Thomas II’s brother, Peter II, Count of Savoy (1203 – 1268), was granted land by Henry III of England between the Strand and the Thames, where he built the Savoy Palace in 1263, on the site of the present Savoy Hotel, which adopted the double-headed eagle as its coat-of-arms. The Manessier's Continuation (also called the Third Continuation), one of the novels of the Story of the Grail was written for Joan, as well as the Life of St. Martha of Wauchier de Denain.

Mother of Amadeus VIII, Bonne of Berry (1362/1365 – 1435), daughter of Jean, Duke of Berry

Michael VIII was succeeded by Andronikos II Palaiologos (1258 – 1332), who married Anna of Hungary, the daughter of Stephen V of Hungary, and sister of Mary of Hungary, wife of Charles II of Naples. Andronikos II’s grandson by Anna was Andronikos III Palaiologos (1297 – 1341), who married Anna of Savoy, the daughter of Thomas II and Joan’s son, Amadeus V of Savoy (1249 – 1323). Andronikos III and Anna were the great-grandparents of Helena Palaiologina. The last ruling monarchs of Cyprus and Jerusalem were John II and Helene’s daughter Charlotte I, who was followed by her usurping half-brother James II, who died in 1473 but had a posthumous son, James III, who died a year later. Venetian merchants had a significant presence in Cyprus and both deaths were suspicious; soon after the death of the baby James the Venetian Republic took control and made Cyprus a Venetian colony.

Genealogy of the Palaiologos Dynasty and Marquises of Montferrat

Michael VIII Palaiologos + Theodora Palaiologina

Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos (1259 – 1332) + Anna of Hungary (the daughter of Stephen V of Hungary, and sister of Mary of Hungary, wife of Charles II of Naples)

Michael IX Palaiologos + Rita of Armenia

Andronikos III Palaiologos + Anna (daughter of Count Amadeus V of Savoy)

John V Palaiologos (1332 – 1391) + Helena Kantakouzene

Manuel II Palaiologos (1350 – 1425) + Helena Dragaš

Theodore II Palaiologos, Despot of Morea, + Cleofa Malatesta

Helena Palaiologina + John II of Cyprus (of the Lusignan dynasty)

Charlotte, Queen of Cyprus

James II of Cyprus + Catherine Cornaro

James III of Cyprus (died in mysterious circumstances as an infant, leaving his mother as the last Queen of Cyprus. His death paved the way for Venice to gain control of Cyprus)

John VIII Palaiologos + Sophia of Montferrat (see below)

Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos (1259 – 1332) + Yolanda (renamed Irene),

Theodore I, Marquess of Montferrat (adopted double-headed eagle) + Argentina Spinola

John II, Marquis of Montferrat + Isabel of Majorca

Theodore II, Marquis of Montferrat + Joanna of Bar (Robert of Bar and Marie of France, Duchess of Bar)

John Jacob of Montferrat (received the investiture as Marquis by Emperor Sigismund) + Joanna of Savoy (see below)

John VIII Palaiologos + Sophia of Montferrat (see above)

Yolande Palaeologina of Montferrat + Aimone, Count of Savoy (son of Amadeus V)

Amadeus VI, the “Green Count” of Savoy + Bonne of Bourbon

Amadeus VII, Count of Savoy + Bonne of Berry (see above)

Amadeus VIII (Antipope Felix V, elevated Duke of Savoy by Sigismund of Luxembourg, founder of the Order of the Dragon) + Mary of Burgundy (d. of Philip the Bold, brother of John, Duke of Berry, Marie of Valois, Charles V of France, and grandfather of Philip the Good, founder of the Order of the Golden Fleece)

Marie of Savoy + Filippo Maria Visconti (see below)

Joanna of Savoy + John Jacob of Montferrat (see above)

Boniface III, Marquis of Montferrat + Maria of Serbia

William IX of Montferrat + Anna of Alençon

Margaret Paleologa + Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua (adopted double-headed eagle)

LUDOVICO GONZAGA, DUKE OF NEVERS (Grand Master of the PRIORY OF SION)

Bianca of Savoy + Galeazzo II Visconti

Gian Galeazzo Visconti + Isabella of France (sister of John, Duke of Berry, Philip the Bold, Marie of Valois and Charles V of France)

Gian Galeazzo Visconti + Caterina Visconti

Gian Maria Visconti

Filippo Maria Visconti (commissioned first Tarot deck with Francesco I Sforza) + Marie of Savoy (see above)

Filippo Maria Visconti + Agnese del Maino

Bianca Maria Visconti + Francesco I Sforza (Order of the Crescent founded by René of Anjou)

Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438 – 1497), married Margaret of Bourbon, niece of Philip the Good who founded the Order of the Golden Fleece

Andronikos II’s second wife was Irene of Montferrat, the daughter William VII, Marquis of Montferrat and Beatrice of Castile, daughter of Alfonso X of Castile. In 1306, when the March of Montferrat shifted to the Palaiologoi from the Aleramici, whose line became extinct, Irene’s children inherited the double-headed eagle. From Theodore I of Montferrat (c. 1290 – 1338) onwards the arms of the marquises contained the heraldic symbol.[15] Theodore I’s daughter, Yolande Palaeologina of Montferrat, married Anna of Savoy’s brother, Aimone, Count of Savoy (1291 – 1343). Aimone’s son and successor, Amadeus VI (1334 –1383), married Bonne of Bourbon, the daughter of Peter I, Duke of Bourbon, and Isabella of Valois, niece of Philip IV “le Bel” of France. They were the parents of Amadeus VII, Count of Savoy (1360 – 1391), who married Bonne of Berry, the daughter of John, Duke of Berry.

Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy (1562 – 1630), knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, claimant of King of Jerusalem

Amadeus VII and Bonne’s son, Amadeus VIII (1383 – 1451) of Savoy, was elevated by Emperor Sigismund to the Duke of Savoy in 1416. Amadeus VIII was a claimant to the papacy from 1439 to 1449 as Felix V in opposition to Eugene IV and Nicholas V, and is considered the last historical antipope. Amadeus VIII’s son and successor Louis, Duke of Savoy (1413 – 1465) married Charlotte I’s aunt, Anne de Lusignan, the sister of John II of Cyprus. Their son Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438 – 1497) married Margaret of Bourbon, the daughter of Charles I, Duke of Bourbon and Agnes of Burgundy, sister of Philip the Good. Philip II’s sister Charlotte married King Louis XI of France (1423 – 1483). Louis XI was the grandson of the mother of René of Anjou, Yolande of Aragon, who was a force in the royal family for driving the English out of France. Louis XI married Charlotte against the wishes of his father Charles VII, who sent an army to compel his son to his will, but Louis fled to Burgundy, where he was hosted by Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, Charles VI’s greatest enemy.

Philip II’s nephew, Charles I (1468 – 1490), Duke of Savoy, the son of Philip II’s brother, Amadeus IX (1435 – 1472), Duke of Savoy and Yolande of Valois, daughter of king Charles VII of France. Charles I was doubly-related to Anne of Lusignan’s niece, the childless Queen Charlotte I of Cyprus. Not only was Charlotte his father Amadeus IX’s first cousin, in such a way that her rights would naturally descend to this line, but she was also the widow of Charles’ paternal uncle Louis of Savoy, Count of Geneva (d. 1482). Charlotte however was without a kingdom, having been exiled in the 1460s from her own legitimate kingdom of Cyprus by her illegitimate half-brother James II of Cyprus. In 1485, in exchange for an annual pension of 4,300 florins, Charlotte ceded her rights in Cyprus, Armenia, and Jerusalem to Charles I, the next legitimate heir in line from Janus. The kingdom itself was held by the republic of Venice, but the Savoy dynasty continued to claim it.

Charles III of Savoy (1486 – 1553), Philip II’s son by his second wife Claudine de Brosse, succeeded his half-brother Philibert II (1480 – 1504), becoming head the Savoy dynasty, which had now also received the titles of the kingdoms of Cyprus, Jerusalem and Armenia, after he married Yolande Louise, the daughter of his cousin Charles I, Duke of Savoy. Charles III married the rich, beautiful and ambitious Infanta Beatrice of Portugal (1504 – 1538), daughter of the richest monarch in Europe at the time, Manuel I of Portugal, a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece and Grand Master of the Order of Christ. Manuel I was the grandson of Edward I of Portugal, the brother of Prince Henry the Navigator, founder of the Order of Christ. Beatrice’s mother Maria of Aragon was the daughter of the Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand II, a knight of the Order of the Golden, and Isabella of Spain.

House of Visconti

The Visconti-Sforza tarot, the oldest surviving tarot cards, commissioned by Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, and by his successor and son-in-law Francesco Sforza, member of the Order of the Crescent

The Visconti ruled Milan until the early Renaissance, first as Lords, then, from 1395, with the mighty Gian Galeazzo (1351 – 1402), the first duke of Milan, who endeavored to unify Northern Italy and Tuscany, as Dukes. Gian Galeazzo was the son of Galeazzo II Visconti (c. 1320 – 1378) and Bianca of Savoy, the sister of Amadeus VI of Savoy. Galeazzo II’s step-brother was Bernabò Visconti (1323 – 1385), the father of Viridis Visconti. Ernest the Iron (1377 – 1424), of the House of Habsburg and a member of the Order of the Dragon, was the son of Leopold III, Duke of Inner Austria (1351 – 1386), and Viridis Visconti. Viridis’ sister Taddea Visconti married Stephen III, Duke of Bavaria, whose daughter was Isabeau of Bavaria, who married Charles VI of France. Their son, Charles VII of France, married Marie of Anjou, the sister of René of Anjou, and fathered Louis XI of France (1423 – 1483).

Genealogy of Francesco I Sforza

Francesco I Sforza (Order of the Crescent) + Bianca Maria Visconti (d. of Filippo Maria Visconti)

Galeazzo Maria Sforza + Lucrezia Landriani

Giovanni delle Bande Nere + Maria Salviati

Cosimo I de' Medici (Order of the Golden Fleece) + Eleanor of Toledo

Lucrezia, Duchess of Modena + Alfonso II d'Este

Galeazzo Maria Sforza + Bona of Savoy (d. of Louis, Duke of Savoy and Anne de Lusignan of Cyprus)

Gian Galeazzo Sforza + Isabella of Naples

Bona Sforza + Sigismund I the Old (Order of the Golden Fleece)

Sigismund II Augustus + Barbara Radziwiłł (accused of promiscuity and witchcraft)

Sigismund II Augustus

Anna Jagiellon + Stephen Báthory (sponsor of John Dee and uncle of Elizabeth Báthory, the “Blood Countess”)

Catherine Jagiellon + John III of Sweden

Sigismund III Vasa (from whom the Vasa kings of Poland were descended. Raised by Jesuits, sponsored alchemist Sendivogius)

Anna Sforza + Alfonso I d’Este

Ludovico Sforza (commissioned The Last Supper) + Beatrice d’Este (double-wedding with Anna Sforza + Alfonso I d’Este orchestrated by Leonardo da Vinci)

Francesco I Sforza (1401 – 1466), a knight of the Order of the Garter

Gian Galeazzo’s first wife was Isabelle of Valois, sister of Marie de Valois, John, Duke of Berry and Philip the Bold. Their daughter Valentina Visconti married her cousin, Louis I, Duke of Orléans, brother of Charles VI of France. Visconti rule in Milan ended with the death in 1447 of Filippo Maria Visconti (1392 – 1447), the son of Gian Galeazzo Visconti by his second wife, Caterina Visconti. Filippo’s second wife was Marie of Savoy, daughter of Amadeus VIII of Savoy, who reigned briefly as antipope Felix V with Filippo’s support. Filippo Maria was succeeded by a short-lived republic and then by his son-in-law Francesco I Sforza (1401 – 1466), a member of the Order of the Crescent, who married his illegitimate daughter Bianca Maria, and established the reign of the House of Sforza. In 1440, as Francesco I’s fiefs in the Kingdom of Naples were occupied by Alfonso I of Aragon, he reconciled himself with Filippo Visconti. In 1442, he allied with René of Anjou and marched against southern Italy. During Francesco I’s reign, Florence was under the command of Cosimo de Medici and the two rulers became close friends. In 1447, Francesco came to power in Milan and rapidly transformed the city into a major center of art and learning that drew the Renaissance humanist Leone Battista Alberti (1404 – 1472).

Francesco and his father-in-law Filippo commissioned the Visconti-Sforza tarot decks, the oldest surviving tarot cards. They commissioned Marziano da Tortona who created the Game of Sixteen Deified Heroes. An example was sent by Jacopo Antonio Marcello, a member of the Order of the Cresent, to Isabella, Duchess of Lorraine, the wife of René of Anjou. A lost tarot pack was described by Martiano as a sixty-card deck with sixteen cards having images of the Roman gods and suits depicting four kinds of birds. The sixteen cards were regarded as “trumps” since in 1449 Marcello recalled that the now deceased Visconti had invented a “a new and exquisite kind of triumphs.”[15] According to tarot historian Gertrude Moakley, the cards’ fanciful images—from the Fool to Death—were inspired by the costumed figures who participated in carnival parades.[16] Like the common playing cards, tarot has four suits of fourteen cards each. In addition, the tarot has a separate 21-card trump suit and a single card known as the Fool, the ancestor of the modern Jack. In Florence, an expanded deck of 97 cards called Minchiate was used, which includes astrological symbols and the four elements, as well as traditional tarot motifs.[17] The earliest reference to minchiate is found in a 1466 letter by Luigi Pulci to Lorenzo de Medici. The word minchiate comes from a dialect word meaning “nonsense” or “trifle,” derived from mencla, the vulgar form of mentula, a Latin word for “phallus.”[18] The word minchione is attested in Italian as meaning “fool.” The Joker and the Fool in the Tarot or Tarock decks share many similarities both in appearance and play function.

Caterina Sforza (1463 – 1509), alchemist

Franceso I’s son, Galeazzo Maria Sforza (1444 – 1476) was the father of Caterina Sforza, whose experimental activities originate the Medici interest in the subject that lasted into the seventeenth century.[20] Caterina was one of the most famous women of the Italian Renaissance, and one of the few women discussed by Machiavelli at length. Machiavelli recounted a well-known incident, when Caterina’s children were threatened with being taken hostage or killed, that she had everything she needed to create others and to prove that she lifted up her skirts and showed her genitalia.[21] Caterina also conducted a series of experiments in alchemy, the results of which were recorded in a manuscript titled Gli Experimenti, as well as recipes for household cleansers, medical remedies, and even poisons.[22] Although the original manuscript is now lost, the text was posthumously transcribed in 1525 by Lucantonio Cuppano.

Cuppano was a follower of Caterina’s son, the famous condottiere Ludovico de’ Medici, known as Giovanni delle Bande Nere, whose father was Giovanni de Medici (1467 – 1498), the grandson of Lorenzo the Elder (c. 1395 – 1440), a brother of Cosimo de Medici the elder. Giovanni and his brother Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de Medici (1463 – 1503), would come under the tutelage of their older cousin, Lorenzo the Magnificent, and studied under Marsilio Ficino. The brothers’ support for Savonarola gained them the nickname of Popolano (“commoner”). In 1501, Lorenzo was suspected of a plot with Cesare Borgia to favor the latter in the conquest of the city. In the early 1500s, Amerigo Vespucci would send most of his famous letters on the “New World” to Lorenzo.

House of Este

Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara (1476 – 1534) by Titian

Marozia (c. 890 – 937), prostitute and mistress of Pope Sergius III, and ancestress of the House of Este and the family of Colonna

The Borgia family arranged several marriages for Cesare Borgia’s sister, the notorious Lucrezia Borgia, that advanced their own political position including Giovanni Sforza, Lord of Pesaro and Gradara, Count of Catignola; Alfonso of Aragon, Duke of Bisceglie and Prince of Salerno; and Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara (1476 – 1534), of the House of Este, who was reputed to be of Davidic descent.[23] The House of Este, an Italian princely family linked with several royal dynasties, including the Habsburgs and the British royal family. The first known member of the House of Este was Margrave Adalbert of Mainz (d. 951?), also known as “il Margravio” or “Adalberto III,” an Italian nobleman tied with the Obertenghi family and a well-known ancestor to the Este, Pallavicini and Malaspina family. Adalbert was either the first-born son of Lambert, margrave of Tuscany (d. 938), the second son of Adalbert II of Tuscany (c. 875 – 915), and Bertha, daughter of Lothair II of Lotharingia, or Lambert's brother Guy, Margrave of Tuscany (d. 929), who was married to Marozia (c. 890 – 937), the daughter of the Roman consul Theophylact, Count of Tusculum, and of Theodora, the real power in Rome. Their descendants controlled the papacy for the next hundred years.

The period of Marozia, the Theophylacti, their relatives and allies, is known as the Saeculum obscurum (“the dark age”), or the “pornocracy” (“rule of prostitutes”), by German historians of the nineteenth century. Marozia was the alleged mistress of Pope Sergius III and was given the unprecedented titles senatrix (“senatoress”) and patricia of Rome by Pope John X. Edward Gibbon wrote of her that the “influence of two sister prostitutes, Marozia and Theodora was founded on their wealth and beauty, their political and amorous intrigues: the most strenuous of their lovers were rewarded with the Roman tiara, and their reign may have suggested to darker ages the fable of a female pope. The bastard son, two grandsons, two great grandsons, and one great great grandson of Marozia—a rare genealogy—were seated in the Chair of St. Peter.” Pope John XIII was her nephew, the offspring of her younger sister Theodora. At the age of fifteen, Marozia became the mistress of Pope Sergius III, whom she knew when he was bishop of Portus.

Genealogy of the House of Este

Ercole I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara + Eleonora d'Aragon (daughter of Ferdinand I of Naples (Order of the Golden Fleece. Her brother Alfonso II of Naples married Ippolita Maria Sforza, daughter of Francesco I Sforza, member of Rene of Anjou’s Order of the Crescent)

Isabella d’Este + Francesco II Gonzaga, Marquess of Mantua

Ferrante Gonzaga (Order of the Golden Fleece and 14th Grand Master of Priory of Sion).

Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua + Margaret Palaeologina (see above)

Louis Gonzaga, Duke of Nevers (Grand Master of the Priory of Sion) + (see above)

Guglielmo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua + Eleonora of Austria (d. of Ferdinand I and Anna Jagellonica)

Margherita Gonzaga + (see below)

Beatrice + Ludovico Sforza (s. Francesco I Sforza, founding member of Rene of Anjou’s Order of the Crescent. Double wedding orchestrated by Leonardo da Vinci)

Gian Galeazzo Sforza + Isabella of Naples (a masque entitled Il Paradiso, with words by Bernardo Bellincioni and sets and costumes by Leonardo da Vinci at their wedding)

Bona Sforza (1494 – 1557) + Sigismund I the Old

Anna Jagiellon + Stephen Bathory (sponsor of John Dee and uncle of Elizabeth Báthory, the “Blood Countess”)

Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara + Lucrezia Borgia (daughter of Pope Alexander VI and Vannozza dei Cattaneia, double wedding orchestrated by Leonardo da Vinci)

In order to counter the influence of another of her alleged lovers, Pope John X, Marozia subsequently married his opponent Guy of Tuscany. Together they attacked Rome, arrested and jailed Pope John X in the Lateran. Either Guy had him killed in 928 or he simply died. Marozia seized power in Rome in a coup d'état. The following popes, Leo VI and Stephen VII, were both her puppets. In 931, she even managed to impose her son by Pope Sergius III as Pope John XI. When Guy died in 929, Marozia negotiated a marriage with his half-brother Hugh of Arles (c. 880 – 947), who had been elected King of Italy.

Adalbert was the father of Oberto I (d. 975), whose the title of count palatine confirmed by Otto the Great. Soon after assuming the Italian throne, Berengar II of Italy reorganised his territories south of the Po River, dividing them into three new marches named after their respective margraves: the marca Aleramica of Aleram, the marca Arduinica of Arduin Glaber (d. 977) of the Arduinici dynasty, and the marca Obertenga of Oberto I. Oberto’s grandson, Albert Azzo II, Margrave of Milan (996 – 1097), is considered the founder of Casa d’Este (House of Este), having built a castle at Este, near Padua, and named himself after the location. Albert Azzo II married Kunigunde of Altdorf, daughter of Welf II, Count of Altdorf (c. 960/70 – 1030), and Imiza of Luxembourg. Imiza was the daughter of Frederick of Luxembourg, the son of Sigfried, Count of the Ardennes, through whom the House of Luxembourg claim descent from the female dragon-spirit Melusina. Albert Azzo II had three sons from two marriages, two of whom became the ancestors of the two branches of the family. Welf I, Duke of Bavaria, the ancestor of the elder branch, the House of Welf, who became known as Guelfs, historical enemies of the Guidelines; Hugh (c. (1055 – 1131) inherited the French County of Maine, but died without heirs; Fulco I, Margrave of Milan (d 1128/35), the ancestor of the younger Italian line of Este. The two surviving branches, with Henry the Lion on the German side, concluded an agreement in 1154 which allocated the family’s Italian possessions to the younger line, the Fulc-Este, who acquired Ferrara, Modena and Reggio. All later generations of the Italian branch are descendants of Fulco d'Este.

Lucrezia Borgia, daughter of Pope Alexander VI, sister to Cesare Borgia, third wife of Alfonso I d’Este (1476 – 1534)

The younger branch of the House of Este included rulers of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio. Ferrara became a significant center of culture under Niccolò d’Este III (1384 – 1441). His successors were his illegitimate sons Leonello d’Este (1407 – 1450) and his brother Borso (1413 – 1471), who was elevated to Duke of Modena and Reggio by Emperor Frederick III in 1452, receiving these duchies as imperial fiefs. By one of his mistresses, Giraldona Carlino, Alfonso V of Aragon had three children, including Maria who married Leonello. Borso was succeeded by a half-brother Ercole I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara (1431 – 1505), who was one of the most significant patrons of the arts in late fifteenth and early sixteenth-century Italy. Ercole I’s brother was Sigismondo d'Este (1433 – 1507), named after his godfather, Emperor Sigismund. Ercole was an admirer of heretic Savonarola, who was also from Ferrara, and sought his advice on both spiritual and political matters. Approximately a dozen letters between them survive. Ercole attempted to have Savonarola freed by church authorities of Florence, but was unsuccessful, and Savonarola was burned at the stake in 1498.[24] In 1503 or 1504, Ercole asked his newly hired composer Josquin des Prez to write a musical testament for him, structured on Savonarola’s prison meditation Infelix ego, resulting in the Miserere.[25] The first definite record of des Prez’s employment is dated 1477, and shows that he was a singer in Aix-en-Provence at the chapel of René of Anjou.[26]

As the capital city of the dukes of d’Este, Ferrara was a center of Italian and European Judaism, with more than 2000 Jews out of a population of 30,000 during its golden age between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Ashkenazi Jews from Germany and Sephardim, welcomed after their expulsion from Spain, lived side by side under the protection of the local authorities. In 1448, upon a request from Leonello d’Este, Pope Nicholas V suppressed the anti-Jewish sermons of the friars. In 1451, Borso declared that he would protect the Jews who entered his lands. In 1473, Ercole I, in opposition to papal demands, protected his Jewish subjects, particularly the moneylenders. In 1481, he authorized Samuel Melli of Rome to buy a mansion in Ferrara and turn it into a synagogue, which is still used. The Spanish Jews were also well received in Ferrara by Ercole I and in Tuscany through the mediation of Jehiel of Pisa (d. 1492) and his sons. Jehiel was on intimate terms with Don Isaac Abravanel, with whom he carried on a correspondence. The Italian rabbi and Kabbalist Johanan Alemanno (c. 1435 – d. after 1504), the teacher of Pico di Mirandola, seems to have lived for years in Jehiel’s house.[27] In 1492, when the first refugees from Spain appeared in Italy, Ercole I allowed some of them to settle in Ferrara, promising to let them have their own leaders and judges, permitting them to practice commerce and medicine, and granting them tax reductions.

Lucrezia de' Medici, Duchess of Ferrara (1519 – 1574), daughter of Cosimo I de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, and wife of Alfonso II d’Este (1533 – 1597)

Ercole I married Eleanor of Naples, whose father was Garter knight Ferdinand I of Naples (1423 – 1494), the son of Alfonso V of Aragon, both of them members of the Order of the Dragon and the Order of the Golden Fleece. In 1491, Ercole I’s son and successor was Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara (1476 – 1534), who married Anna Sforza, the daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza and Bona of Savoy, another daughter of Philip II, Duke of Savoy and Margaret of Bourbon. In 1464, Bona of Savoy was to have been betrothed to Edward IV of England, until his secret marriage to Elizabeth Woodville was revealed. Ercole II d’Este (1508 – 1559), the son of Alfonso I by his second wife Lucrezia Borgia, married Renée of France, daughter of Louis XII of France. Their son Alfonso II d’Este (1533 – 1597) married Lucrezia, a daughter of Cosimo I de Medici.

Ercole II d'Este (1508 – 1559), Duke of Ferrara

After the death of Pope Paul III, born Alessandro Farnese, who had showed favor to the Jews, a period of strife, persecution, and despondency set in. In 1537, Jacob Abarbanel, who was one of the two brothers of Isaac Abarbanel, was instrumental by influencing Cosimo I de Medici in allowing Jews and Marranos from Spain and Portugal to settle in Florence. Cosimo’s wife, Eleonora di Toledo, was the daughter of Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, Viceroy of Naples. Before eventually settling in Tuscany, Eleonora was brought up in Naples at the household of Jacob Abarbanel’s son Don Samuel Abarbanel and daughter-in-law Benvenida, whom she continued to honor as her mother.[28] Eleonora’s father was the lieutenant-governor of Emperor Charles V and brother of the Duke of Alba. Through her father’s side, Eleanor was the third cousin of the Emperor since their great-grandmothers were daughters of Fadrique Enríquez de Mendoza (1390 – 1473), grandson of King Alfonso XI of Castile. Mendoza’s father was Alonso Enríquez, was the son of Fadrique Alfonso, 25th Master of the Order of Santiago, from a Jewish woman named Paloma.[29] Alonso Enríquez’s half-sister was Juana, Queen of Aragon, mother of Ferdinand II of Aragon, the husband of Queen Isbella of Spain. There has been an attempt to introduce the Inquisition into the Neapolitan realm, then under Spanish rule, and Emperor Charles V neared the point of exiling the Jews from Naples when Benvenida caused him to defer the action. A few years later, in 1533, a similar decree was proclaimed, when Jacob’s brother Samuel Abarbanel and others were able through their influence to avert for several years the execution of the edict.

In 1532, Ercole II had issued another permit allowing Jews from Bohemia and other countries in Central Europe to come and settle in Ferrara. In 1524 and 1538, Ercole II encouraged the Marranos and in 1553 they were allowed to return to the Jewish faith. In 1540, an invitation to settle in Ferrara was extended to the persecuted Jews of Milan and a year later to those banished from the kingdom of Naples.[30] The situation declined after 1597, when Alfonso II died without a male heir, when d’Este court abandoned the city and the papacy took control. The d’Este left for Modena, followed by a number of Jews.[31]

Palazzo Vecchio

Painting of the Palazzo and the square in 1498, during the execution of Savonarola for heresy

Cosimo I de Medici (1519 – 1574), Grand Duke of Tuscany, knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece

Cosimo I de Medici was an enthusiast of alchemy, a passion he inherited from his grandmother Caterina Sforza.[32] Cosimo I became duke of Florence in 1537 and was made grand duke of Tuscany only in 1569. In 1541, as part of his political agenda, and also because his wife Eleanor of Toledo had just given him an heir, Francesco I de Medici (1541 – 1587), Cosimo I decided to move his principal residence from the old Medici Palace on Via Larga to the headquarters of the former republican government, the Palazzo della Signoria, named after the Signoria of Florence, the ruling body of the Republic of Florence. When Cosimo later removed to Palazzo Pitti, he officially renamed the palace to the Palazzo Vecchio, the “Old Palace.” The first alterations to Palazzo Vecchio date from 1342-43, during the brief tyranny of the crusader Walter VI of Brienne (c. 1304 – 1356), and most importantly during the decades between 1440-60, when Cosimo the Elder de Medici took over the government of the city. The most imposing chamber, the Salone dei Cinquecento (“Hall of the Five Hundred”) was commissioned by Savonarola who wanted it as a seat of the Grand Council. Later the hall was enlarged by Giorgio Vasari (1511 – 1574), an artist, architect and friend of Michelangelo, so that Cosimo I could hold his court in this chamber. The Palazzo Vecchio holds a copy of Michelangelo’s David.

Genealogy of the Medici

Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici + Piccarda Bueri

Cosimo de' Medici the Elder (sponsor of Marsilio Ficino, and member of Order of the Crescent founded by René of Anjou) + Contessina de' Bardi

Piero di Cosimo de' Medici + Contessina de' Bardi

Lorenzo de' Medici (Lorenzo the Magnificent) + Clarice Orsini

Piero the Unfortunate + Alfonsina Orsini

Lorenzo de Medici, Duke of Urbino + Madeleine de La Tour d'Auvergne

Catherine de Medici (sponsor of Nostradamus, practitioner of Black Mass) + Henry II of France

Claude of France + Charles III, Duke of Lorraine

Henry II, Duke of Lorraine + Margherita Gonzaga

Christina of Lorraine + (patron of Galileo)

Henry III of France (educated in Black Arts by his mother) + Louise of Lorraine

Clarice de Medici + Filippo Strozzi the Younger

Pope Leo X

Lucrezia de Medici + Jacopo Salviati

Maria Salviati + Giovanni delle Bande Nere

Giuliano de' Medici + Fioretta Gorini

Pope Clement VII

Lorenzo the Elder + Ginevra Cavalcanti

Pierfrancesco the Elder + Laudomia di Agnolo Acciaioli

Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici (with his brother, educated by Marsilio Ficino, sponsors of Amerigo Vespuci, supporters of heretic Savonarola)

Giovanni de' Medici il Popolano + Caterina Sforza (g-d of Francesco I Sforza, member of Order of the Crescent, founded by René of Anjou, Grand Master of the Priory of Sion. Conducted alchemical experients)

Giovanni delle Bande Nere + Maria Salviati (see above)

Cosimo I de' Medici (Order of the Golden Fleece) + Eleanor of Toledo (brought up in the household of Jacob Abarbanel’s son Don Samuel Abarbanel and daughter-in-law Benvenida)

Lucrezia, Duchess of Modena + Alfonso II d'Este (ally of Rudolf II, supporter of John Dee)

Francesco I de' Medici + Joanna of Austria (daughter of Ferdinand I and Anna Jagellonica)

Marie de Medici (Cosimo Ruggeri, who had been the trusted sorcerer of Catherine de Medici, was a personal friend of Marie de Medici’s favorites, Concino Concini and his wife Leonora Dori, who was later burned at the stake for witchcraft) + Henry IV of France

Eleanor of Toledo (1522 – 1562), wife of Cosimo I de Medici, and her son Francesco I de Medici

In the mythology the Medici had been articulating since Cosimo I established the dynasty, a correspondence was drawn between cosmos and Cosimo, and Jupiter was regularly associated with Cosimo I, and the first of the “Medicean gods,” as Vasari referred to them.[33] The horoscope of the city of Florence, as was commonly cast since the Middle Ages, was employed to suggest the astrological fate of Medici rule. Cosimo I had classical theogonies allegorically reinterpreted to resemble the history of the house of Medici. This mythological program was best articulated in Vasari’s frescoes decorating the Apartment of the Elements in the Palazzo Vecchio. The Apartment of the Elements consists of five rooms that were the private quarters of Cosimo I. The walls contain allegorical frescoes depicting Fire (The Forge of Vulcan), Earth (The Reign of Saturn), and Water (The Birth of Venus). The frescoes of each room downstairs present a mythologized history of the member of the Medici family it honors. Right below the Apartment of the Elements is the Apartment of Leo X, displaying the Medici pantheon. Each room of the Apartment of Leo X is dedicated to a member of the Medici family who was instrumental in establishing the dynasty. As Vasari put it, “There is nothing painted upstairs that does not correspond to something painted downstairs,” corresponding with the Hermetic dictum of “As above so below.”[34]

The ceiling Apartment of the Elements, which serves as the representation of Air, has smaller panels of the Times of Day, and of Truth, Justice, Peace, and Fame. In the center is the very rare subject of The Castration of Ouranos by Saturn, derived from the Theogony of Hesiod by way of Boccaccio. In his book of instructive conversations with Francesco I, Vasari explains first interprets the castration in terms of Aristotelian cosmology: “Cutting off the heat as form, and its falling into the sea as matter, gave rise to the generation of earthly things that are fallen and corruptible and mortal, generating Venus from the sea foam.” When Francesco I asks about the choir of figures surrounding the central figures, Vasari share an exegesis on the ten Sephiroth of the Kabbalah.[35]

The correspondence between the paintings in the Room of Jupiter which present the childhood of Cosimo I, is the core of the mythological narratives developed throughout the paintings of the two apartments. Born of Ops and Saturn, the child Jupiter was saved by his mother from the cruelty of his father Saturn, who tended to eat his offspring. The mother hid baby Jupiter in a cave in Crete where was he was reared by two nymphs. One of them, Amalthea, was represented as a goat and associated with divine Providence, while the other nymph Melissa was divine Knowledge, suggesting that Cosimo I absorbed these virtues in the cradle. In memory of Amalthea, Jupiter added the sign of Capricorn, Cosimo's zodiac sign. The seven stars of Capricorn became emblems of the seven virtues, three theological and four moral. In essence, Cosimo was endowed with divine providence and knowledge by Jupiter and received the seven virtues from Capricorn.[36]

House of Gonzaga

Coat of arms of the House of Gonzaga

Ludovico III Gonzaga (1412 – 1478), Marquis of Mantua and Barbara of Brandenburg, a niece of Emperor Sigismund, with their children

The arms of the marquises of Montferrat contained the double-headed eagle until the last legitimate male heir of the Palaiologos family, William IX’s brother Giovanni Giorgio (1488 – 1533), and the city was inherited by Federico II Gonzaga (1500 – 1540) who added the heraldic symbol to his own.[37] The House of Gonzaga were an Italian princely family that ruled Mantua, in northern Italy, from 1328 to 1708. They also ruled Monferrato in Piedmont and Nevers in France, as well as many other lesser fiefs throughout Europe. Federico II Gonzaga’s great-grandfather, Gianfrancesco I Gonzaga (1395 – 1444), became a famous general and was rewarded in 1432 for his services to Emperor Sigismund with the title of marquess of Mantua for himself and his descendants, an investiture that legitimatized the usurpations of the house of Gonzaga. Under Gianfrancesco, the first school inspired by humanistic principles was founded in 1423 in one of the family’s villas near Mantua by Vittorino de Feltre. Artists also found their way to Mantua, notably Andrea Mantegna and Leon Battista Alberti, and during the fifteenth century the capital city and its dependencies were embellished and transformed.

Genealogy of the House of Gonzaga

Ludovico II Gonzaga + lda (d. of Obizzo III d'Este, Marquis of Ferrara)

Francesco I Gonzaga + Margherita Malatesta

Gianfrancesco I Gonzaga, Marquess of Mantua (first Gonzaga to bear the title of marquess, which he obtained from Emperor Sigismund) + Paola Malatesta

Ludovico III Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua + Barbara of Brandenburg (niece of Emperor Sigismund)

Federico I Gonzaga, Marquess of Mantua + Margaret of Bavaria (d. of Albert III, Duke of Bavaria)

Clara Gonzaga + Gilbert, Count of Montpensier

CHARLES III, DUKE OF BOURBON (Grand Master of the PRIORY OF SION, ORDER OF THE FLEUR DE LYS)

Renée de Bourbon + Antoine, Duke of Lorraine (see below)

Louise de Bourbon + Louis, Prince of La Roche-sur-Yon

Louis, Duke of Montpensier + Jacqueline de Longwy

Charlotte of Bourbon + William the Silent of Orange

Countess Louise Juliana of Nassau + Frederick IV, Elector Palatine

Frederick V of the Palatinate + Elizabeth Stuart (see below)

Francesco II Gonzaga + Isabella d’Este

Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua + Margaret Paleologa (see below)

LUDOVICO GONZAGA, DUKE OF NEVERS (Grand Master of the PRIORY OF SION)

Guglielmo Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua + Eleanor, Duchess of Mantua (see below)

FERRANTE GONZAGA (Grand Master of the PRIORY OF SION, ORDER OF THE FLEUR DE LYS)

Ferrante Gonzaga (1507 – 1557), knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece and purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion

Gianfrancesco’s son, Ludovico III Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantu (1412 – 1478), married Barbara of Brandenburg, a niece of Emperor Sigismund. Their son, Federico I Gonzaga, Marquess of Mantua (1441 – 1484), married Margaret of Bavaria, the daughter of Albert III, Duke of Bavaria, the son of Ernest, Duke of Bavaria (1373 –1438) and Elisabetta Visconti. As ally of the House of Luxembourg, Ernest backed his deposed brother-in-law Wenceslaus, Sigismund’s brother, against Rupert of the Palatinate, as well as Sigismund in his wars against the supporters of Jan Hus. Federico I’s daughter Clara Gonzaga married Gilbert, Count of Montpensier, and was the mother of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon (1490 – 1527), a purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion.

Clara’s brother, Francesco II Gonzaga (1466 – 1519) married Isabella d’Este, the sister of Alfonso I d’Este, and fathered Federico II Gonzaga. Isabella and Francesco II’s son, Ferrante Gonzaga (1507 – 1557), was a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece and listed as a purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion, after his first cousin Charles III, Duke of Bourbon and Leonardo da Vinci. Charles III was the second son of Count Gilbert of Montpensier by his wife Clara Gonzaga, the sister of Ferrante’s father Francesco II Gonzaga. Ferrante was one of da Vinci’s most zealous patrons. At the age of sixteen, Ferrante was sent to the court of Spain as a page to the future emperor Charles V, Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Fleece, to whom Ferrante remained faithful for his whole life.

Louis Gonzaga, Duke of Nevers (1539 – 1595), Grand Master of the Priory of Sion

A cadet branch of the Gonzagas of Mantua became dukes of Nevers and Rethel in France when Louis Gonzaga, Duke of Nevers (1539 – 1595), Ferrante’s nephew and successor as Grand Master of the Priory of Sion, married the heiress. Louis was the third child of Federico II Gonzaga (1500 – 1540) and Margaret Palaeologina, the daughter of William IX of Montferrat and his wife Anne of Alençon. William IX was descended from the grandson of Theodore I, Marquess of Montferrat, Theodore II, Marquis of Montferrat (d. 1418), who married Joanna of Bar, the daughter of Robert of Bar and Marie of Valois. His son, John Jacob of Montferrat (1395 – 1445), who received the investiture as Marquis by Emperor Sigismund, married Joanna of Savoy, the daughter of Amadeus VII, Count of Savoy. William IX of Montferrat was John Jacob’s grandson. Anne of Alençon’s mother was the third child of René, Duke of Alençon and his second wife Margaret of Lorraine, daughter of Ferry II of Vaudémont and Yolande of Bar.

Da Vinci Code

Beatrice d’Este; Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci, purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion; Ludovico Sforza (1452 – 1508), purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion; Da Vinci’s la Belle Ferroniere.

Presumed self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci (c. 1510), purportedly succeeded Charles III, Duke of Bourbon as Grand Master of the Priory of Sion

Isabella d’Este was a renowned patron and collector who supported artists such Andrea Mantegna, Titian and Leonardo da Vinci, who supposedly preceded Charles III, Duke of Bourbon, as Grand Master of the Priory of Sion. Isabella has been proposed as a plausible candidate for da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Evidence in favor of Isabella as the subject of the famous work includes Leonardo’s drawing “Isabella d’Este” from 1499 and her letters of 1501–1506 requesting the promised painted portrait.[38] Isabella was also an innovator of new dances, having been instructed in the art by Ambrogio, a Jewish dancing master.[39] The marriage of Isabella’s sister Beatrice d’Este to Francesco I Sforza’s son, Ludovico Sforza (1452 – 1508), was a double-wedding, with Alfonso I d’Este and Anna Sforza, orchestrated by Leonardo da Vinci.

Isabella d'Este (1474 – 1539)

Ludovico, da Vinci’s chief patron, was known to history as Il Moro, literally meaning “The Moor,” an epithet said by Francesco Guicciardini, a friend and critic of Machiavelli, to have been given to Ludovico because of his dark complexion. Ludovico was famed as a patron of da Vinci and other artists, and is probably best known as the man who commissioned da Vinci’s The Last Supper. Ludovico’s nephew and Anna Sforza’s btother, Gian Galeazzo Sforza (1469 – 1494), married Isabella of Naples (1470 – 1524), the granddaughter of Ferdinand I of Naples. At Gian and Isabella’s wedding, a masque or operetta was held, entitled Il Paradiso, with words by Isabella’s cousin, Bernardo Bellincioni (1452 – 1492), and sets and costumes by da Vinci. Bellincioni, who had begun his career in the court of Lorenzo the Magnificent in Florence, was also a court poet of Ludovico Sforza.

Da Vinci visited the home of the Medici and through them came to know Marsilio Ficino. Also associated with the Platonic Academy of the Medici was Leonardo’s contemporary, the Christian Kabbalist Pico della Mirandola. Da Vinci was often called “the magician of the Renaissance.”[40] In 1480, da Vinci was living with the Medici and working in the Garden of the Piazza San Marco in Florence, a Neoplatonic academy of artists, poets and philosophers that the Medici had established. In The Last Supper, da Vinci portrays the twelve apostles in four groups of three, corresponding to the signs of the zodiac, organized into four seasons. In the center is Jesus as the sun. The disciples seated at The Last Supper, which is the central theme of Dan Brown’s novel, are grouped in four groups of three, talking only among themselves, corresponding to the four elements in the Zodiac, with Christ in the middle, as the Sun.

According to Keith Stern, after da Vinci’s death, it was commonly accepted that he had been a homosexual. Freud, in his Leonardo da Vinci, A Memory of His Childhood, stated that it was doubtful whether Leonardo ever embraced a woman in passion. Court records of 1476, when da Vinci was aged twenty-four, show that he and three other young men were charged with sodomy with a well-known male prostitute. The charges were dismissed for lack of evidence. There is speculation that since one of the accused, Lionardo de Tornabuoni, was related to Lorenzo de Medici, the family exerted its influence to secure the dismissal.[41]

A folio by da Vinci’s includes a page of drawings by a hand other than his, one of which is a doodle depicting an anus, identified as “Salai’s bum,” being pursued by penises on legs.

Da Vinci’s Saint John the Baptist, possibly modeled on his lover Salai

Much has been written about da Vinci’s supposed homosexuality, and its influence on his art, particularly in the androgyny and eroticism evident in depictions of Saint John the Baptist and Bacchus and more explicitly in a number of erotic drawings.[42] Da Vinci’s model for these works is suspected to have been Gian Giacomo Caprotti da Oreno, who is thought to have been his lover. He is better known by his name given to him by da Vinci, Salai, Tuscan slang for “devil.” Vasari described Salai as “a graceful and beautiful youth with curly hair, in which Leonardo greatly delighted,” and although da Vinci referred to him as “a liar, a thief, stubborn and a glutton,” and claimed that he stole from him on at least five occasions, he kept him in his household for more than twenty-five years.[43] A number of drawings among the works of da Vinci’s and his pupils make reference to Salai’s sexuality. There is a drawing modelled on da Vinci’s painting John the Baptist and called The Angel Incarnate, appearing to represent Salai with an erect phallus. A folio by da Vinci’s includes a page of drawings by a hand other than his, one of which is a crudely drawn doodle depicting an anus, identified as “Salai’s bum,” being pursued by penises on legs.[44]

Sandro Botticelli (c. 1445 – 1510), purported predecessor of of da Vinci as Grand Master of the Priory of Sion

Purportedly, da Vinci had succeeded as Grand Master of the Priory of Sion after Sandro Botticelli, Yolande de Bar and her father René of Anjou. Botticelli’s chief patron was Lorenzo de Medici, along with the Este, the Gonzaga families. Botticelli himself studied under Filippo Lippi (c. 1406 – 1469) and Mantegna, both of whom had been patronized by René of Anjou. According to Giorgio Vasari (1511 – 1574) the first art historian of the Renaissance, Botticelli became a follower of Savonarola, who preached in Florence from 1490 until his execution in 1498.[45] In late 1502, four years after Savonarola’s death, Isabella d’Este wanted a painting created in Florence. Her agent Francesco Malatesta informed her that her first choice, Perugino, was away, Filippino Lippi fully booked, but Botticelli was willing and available. Isabella however preferred to wait for Perugino’s return.[46]

Titian’s The Bacchanal of the Andrians (1523–1526)

Titian (c. 1488/90 – 1576)

In 1516, Titian (c. 1488/90 – 1576) made contact with Isabella’s brother Alfonso I d'Este, for whom he was to work for a decade on paintings destined for the Camerino d’Alabastro (“Alabaster Chamber”), in the ducal palace. In this period he produce a series of paintings of Dionysian themes: the Worship of Venus, the Bacchanal of the Andrians, and Bacchus and Ariadne. The Worship of Venus is based on a description by the late antique writer Philostratus, in his Imagines, of a painting of cupids gathering apples in the presence of Venus amid a tree-girt landscape. In the Bacchanal of the Andrians, which is set on the island of Andros, a sleeping nymph and a urinating boy are seen in the lower right foreground while men and women celebrate with jugs of wine. Bacchus and Ariadne, considered “perhaps the most brilliant productions of the neo-pagan culture or ‘Alexandrianism’ of the Renaissance, many times imitated but never surpassed even by Rubens himself.”[47] The painting depicts Theseus, whose ship is shown in the distance and who has just left Ariadne at Naxos, when Bacchus arrives, jumping from his chariot, drawn by two cheetahs. Having fallen in love with Ariadne, Bacchus asked her to marry him, offering her the sky as a wedding gift, in which one day she would become a constellation. Her constellation is shown in the sky.

The Fortune Teller by Caravaggio (1571 – 1610), Gypsy girl reading palm of boy modeled by Caravaggio’s student and lover, Mario Minniti

Caravaggio (1571 – 1610)

In 1584, Caravaggio (1571 – 1610) began his four-year apprenticeship to the Milanese painter Simone Peterzano, described in the contract of apprenticeship as a pupil of Titian. Throughout his life, Caravaggio was to receive help from various members of the Sforza-Colonna family, particularly from Costanza Colonna. The Colonna family is a branch of the Counts of Tusculum, who are traced back to Peter de Columpna (1099 – 1151), a descendant of Alberic II of Spoleto, the son of Marozia. Costanza Colonna was the widow of Francesco I Sforza di Caravaggio (d. 1576), the great-grandson of Ludovico Sforza and his mistress Lucrezia Crivelli. Caravaggio’s connections with the Colonnas led to a stream of important church commissions, including the Madonna of the Rosary, and The Seven Works of Mercy. The commissioner of the Madonna of the Rosary is uncertain, but one possibility is that it was Cesare d’Este.[48] After being offered to Vincenzo I Gonzaga (1562 – 1612), the painting was offered to the Dominican church in Antwerp.[49] Vincenzo I Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, was a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, and nephew of Louis Gonzaga, another purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion.

The Musicians, by Caravaggio

Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte (1549 – 1627)

The Fortune Teller shows a boy having his palm read by a Gypsy girl, who is stealthily removing his ring as she strokes his hand. The work attracted the patronage of Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte (1549 – 1627), one of the leading connoisseurs in Rome. Del Monte was appointed as auditor for Cardinal Alessandro Sforza, before being finally admitted into the court of Cardinal Ferdinando de Medici (1549 – 1609), the son of Cosimo I de Medici. Del Monte’s interests also included alchemy.[50] Caravaggio executed his only known fresco on the vaulted ceiling of Del Monte’s own alchemy laboratory in the Villa Ludovisi, depicting an allegory of the alchemical triad of Paracelsus: Jupiter for sulphur and air, Neptune for mercury and water, and Pluto for salt and earth. Each figure is identified by his beast: Jupiter by the eagle, Neptune by the hippocamp, and Pluto by the three-headed dog Cerberus. Jupiter is reaching out to move the celestial sphere in which the Sun revolves around the Earth. Galileo was a friend of Del Monte but had yet to advance his new cosmology.