5. Gog & Magog

Altai Mountains

According to Jewish eschatology, Gog and Magog are enemies that will be defeated by the Messiah at the beginning of the End Times, which would usher in the age of the Messiah. Although biblical references to Gog and Magog are relatively few, they assumed an important place in apocalyptic literature and medieval legend. Jewish eschatology viewed Gog and Magog as enemies whose defeat ushers the age of the Messiah. They are also discussed in the Quran. In the Book of Revelation, Gog and Magog are applied to the evil forces that will join with Satan in the great struggle at the End of Time. After Satan has been bound and chained for a thousand years, he will be released and will rise up for a final time against God. He will gather “the nations in the four corners of the Earth, Gog and Magog” to attack the saints and Jerusalem. God will send fire from heaven to destroy them and will then preside over the Last Judgment.

In both Jewish and Christian apocalyptic writings and other works, Gog and Magog were also identified with the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, who are described as great warriors who will accompany the return of the messiah or the arrival of the antichrist.[1] As related by Colin Gow in The Red Jews: Anti-Semitism in an Apocalyptic Age: 1200-1600, the Lost Tribes of Israel, who came to be known in Jewish lore of the Middle Ages as “Red Jews”—a conflation of three separate traditions: the prophetic references to Gog and Magog, the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, and an episode from the Alexander Romance—were believed to reside in Central Asia, and were expected to come forth to aid the Messiah in his conquest of the world. Their central role in the events of the End Times inspired numerous attempts over the centuries to identify them with specific nations, including the Scythians, Huns, Goths, Turks, Khazars and Mongols. Like the Scythians, the Mongols as well claimed their ancestors to be Gog and Magog. As traveler and Friar Riccoldo da Monte di Croce recorded in c. 1291, the Mongols “say themselves that they are descended from Gog and Magog: and on this account they are called Mogoli, as if from a corruption of Magogoli.”[2] Marco Polo placed Gog and Magog among the Tartars in Tenduc, , but then claims that the names Gog and Magog are translations of the place-names Ung and Mungul, inhabited by the Ung and Mongols respectively.[3]

Most importantly, these claims would eventually provide the basis for later formulations of the Aryan Race. The Europeans, descendants of the supposed Aryan race, today known more popularly as the Indo-Europeans, are also referred to as “Caucasians” because they supposedly emerged from the area of the Caucasus mountains. These theories were formulated by European scholars in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, to associate Europeans with the history of occult knowledge, purportedly preserved through history by the progeny of the Fallen Angels, whose race was continued in a combination of Gog and Magog the Lost Tribes of Israel, a people known as Scythians, who settled in the steppes north of the Caucasus, from the Don River basin in Southern Russia and Ukraine, to the Altai Mountains of Mongolia.

Occult legends place the home of the Aryan race in the mythical land of Shambhala, from Tibetan Buddhist legend, which was typically located in either in Xinjiang, in Western China, or the Altai Mountains, a mountain range in south-central Siberia, where Russia, China, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan come together. The Altai Mountains are the reputed source of the early form of spirit or “divine” communication known as shamanism, regarded among occultists as the “Oriental Kabbalah,” a supposed remnant of the migrations of Aryan survivors of Atlantis. Through the use of a psychotropic drug, the shaman was supposedly able to enter trance or dissociative states that allowed him to communicate with the other world. Early shamanistic practices are traced to the heretical Magi, whose nocturnal and orgiastic rites were combined with the Haoma, an intoxicating drink prepared from the sacred plant of Zoroastrianism.[4] Haoma had its equivalent in Soma, a Vedic ritual drink of importance among the early Indo-Iranians, and the subsequent Vedic and greater Persian cultures. It is frequently mentioned in the Rigveda and the Avesta, the primary collection of sacred texts of Zoroastrianism. The Haoma has long been associated with the Tree of Knowledge.[5] The Persians would say, “Haoma is the first of the trees, planted by Ahura Mazda in the fountain of life. He who drinks of its juice never dies!”[6] Although there has been much speculation concerning what is most likely to have been the identity of the original plant, there is no solid consensus on the question. It is described as being prepared by extracting juice from the stalks of a certain plant. Plutarch described a sacrifice offered by the Magi of a wolf made to the spirit of evil. “In a mortar,” he says, “they pound a certain herb called Haoma at the same time invoking Hades [Ahriman: the Zoroastrian devil], and the powers of darkness, then stirring this herb in the blood of a slaughtered wolf, they take it away and drop it on a spot never reached by the rays of the Sun.”[7]

The Altai mountains are also claimed as the original homeland of the Turks, a myth that the Pan-Turkism shared with the Nazis. Medieval Chinese sources report an etymology of the name “Turk” as derived from “helmet,” explaining that this name derives from the shape of a mountain where they worked in the Altai Mountains.[8] Turkic languages show some similarities with the Mongolic, Tungusic, Koreanic, and Japonic languages. These similarities led some linguists to propose an Altaic language family, though this proposal is widely rejected by historical linguists. Apparent similarities with the Uralic languages even caused these families to be regarded as one for a long time under the Ural-Altaic hypothesis. The Ural-Altaic family of languages are also known as the Turanian family, after the Persian word Turan for Turkestan. The word Turan is derived from Tur, the son of Emperor Fereydun in ancient Persian mythology. In the Shahnameh, an epic poem written by Ferdowsi of the ninth century AD, Tur is identified with the Turks, and the land of Turan refers to the inhabitants of the eastern-Iranian border and beyond the river Oxus. Today known as the Amu Darya, the Oxus is a major river in Central Asia, that flows along the border between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

The Scythians were the originators of the haplogroup R-M17, also known as R1a1, which would play a prominent role in the debate about the origins of the Aryans.[9] Haplogroup R1a, a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup, which is distributed in a large region in Eurasia, extending from Scandinavia and Central Europe to southern Siberia and South Asia. To date, scientists have discovered twenty main haplogroups for men. These are identified by the following letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S and T. These main haplogroups are further subdivided into one or more levels called sub-haplogroups or subclades, which are labeled by alternating numbers and letters. Haplogroup R is the most common male haplogroup of Europe and it is divided into sub-haplogroups R1 and R2. Haplogroup R1 is further divided into sub-haplogroups R1b, the most common haplogroup in Western Europe, and R1a (especially R1a1), which is unique for its diversity and distribution, is found in disparate pockets of concentration in Poland, Northern India and the Altai Mountains of northwestern Mongolia.[10] R1a is distributed at high concentrations in the Balkans, including Macedonia, and particularly the Altai Mountains of Northern Mongolia, linking the mysterious heritage of Alexander with the supposed Lost Tribes of Israel and Gog and Magog. However, that curious racial and cultural immixture has been confused through occult legend to produce the myth of the Aryan race.

R1a1 concentrations

R1a is found in high concentrations in the Altai region.[11] The R1a haplogroup has been identified in the 24,000 year-old remains of the so-called “Mal’ta boy” from the Altai.[12] R1a shows a strong correlation with Indo-European languages of Southern and Western Asia and Central and Eastern Europe, being most prevalent in Eastern Europe, West Asia, South Asia and Central Asia. Kivisild et al. have proposed an origin in either south or west Asia, while Mirabal et al. see support for both south and central Asia. Other studies suggest Ukrainian, Central Asian and West Asian origins for R1a1a.[13] Spencer Wells proposes central Asian origins, suggesting that the distribution and age of R1a1 points to an ancient migration corresponding to the spread of the Kurgan people in their expansion from the Eurasian steppe.[14]

Three genetic studies in 2015 gave support to the Kurgan theory of Gimbutas regarding the Indo-European Urheimat (original homeland), a concept that was also of particular concern to the Nazis.[15] The Kurgan hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory or Kurgan model) or steppe theory, is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe, Eurasia and parts of Asia. It postulates that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE). The term is derived from the Russian kurgan, meaning tumulus or burial mound. The mobility of the Kurgan culture facilitated its expansion over the entire region, and is attributed to the domestication of the horse, and later the use of early chariots.

Haplogroup R1a has been found in ancient fossils associated with the Corded Ware culture and Urnfield culture; as well as the burial of the remains of the Sintashta culture, Andronovo culture, the Pazyryk culture, Tagar culture and Tashtyk culture, the inhabitants of ancient Tanais [Don River], and in the Tarim mummies, and the aristocracy of the Xiongnu; the Tarim mummies are a series of mummies discovered in the Tarim Basin in present-day Xinjiang, China, which date from 1800 BCE to the first centuries BCE. But “the most prominent Chinese grave sites were in Astana,” the capital of modern-day Kazakhstan, and a military outpost for China between the Jin dynasty (265–420) and the Tang dynasty.[16] Han Kangxin found the closest relatives of the earlier Tarim Basin population in the populations of the Afanasevo culture situated immediately north of the Tarim Basin, and the Andronovo culture that spanned Kazakhstan and reached southwards into West Central Asia and the Altai.[17] Victor H. Mair’s team concluded that the mummies are Western Eurasian, perhaps speakers of Indo-European. Upon examining these East Asian Mongoloid remains, Mair’s team reported:

The new finds are also forcing a reexamination of old Chinese books that describe historical or legendary figures of great height, with deep-set blue or green eyes, long noses, full beards, and red or blond hair. Scholars have traditionally scoffed at these accounts, but it now seems that they may be accurate.[18]

R1a1, which is found all over Armenia, Georgia and Eastern Europe in general, including the Sorbs, the Poles, and many people of central Europe, is also found in Finland, and many R1a1 people went west to Scotland and Scandinavia. R1a1 was found at elevated levels among a sample of the Israeli population who self-designated themselves as Ashkenazi Jews, and is possessed by about half of Ashkenazi Levites.[19] Particularly high concentrations are found among the Pashtuns of Afghanistan, who claim descent from both Alexander the Great as well as the Lost Tribes of Israel.[20]

Scythians

In 721 BC, when the northern Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Assyrians, after that time the Ten Tribes who had been living there were dispersed to land of the Medes, in Iran and Armenia, and were henceforth considered “lost.” The river is referred to as Gozan in the Bible, according to which, in addition to parts of ancient Iran, it was to this region that the Lost Tribes had been dispersed by the Assyrians. According to 2 Kings 17:5-6:

Then the king of Assyria came up throughout all the land, and went up to Samaria, and besieged it three years. In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away into Assyria, and placed them in Halah and in Habor by the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes.

The Medes, whom Herodotus called Arians, were made out by scholars of the Enlightenment to be the ancestors of the Europeans, the pure-bred Aryans. According to Greek mythology, the Medes were descended from Medea the Colchian witch from the story of Jason and the Argonauts and his quest for the Golden Fleece. According to the legend, Medea later married Aegeas of Athens after whom the Aegean Sea is named. Paradoxically, according to a description by Herodotus, the Colchians who dwelt in a land located along the western slope of the Caucasus Mountains near the Black Sea, in what is now the state of Georgia, were black, and probably Jewish. Like the Jews of Palestine whom he referred to as “Phoenicians,” Herodotus also regarded the people of Colchis as deriving from an “Egyptian colony.” He not only pointed to the Colchians’ “black skin and woolly hair” as evidence, but also to their oral traditions, language, methods of weaving, and practice of circumcision. Saint Jerome, writing during the fourth century AD, called Colchis the “Second Ethiopia.”[22]

The Capture of the Golden Fleece by Jean Francois de Troy.

From Medea, the Lost Tribes would have spread out further into Southern Russia and Central Asia, thus purportedly merging with the Scythians, who were identified by Josephus and others with Gog and Magog.[23] According to Herodotus, the Scythians were descended from an echidna (“she-viper”), which in several respects resembles the Echidna, half woman, half serpent of Greek myth, where she is the mate of the serpent Typhon and was the mother of many of the most famous monsters. Echidna was the daughter of either the sea deities Phorcys and Ceto or Tartarus and Gaia. According to the Orphic tradition, however, Echidna was the daughter of Phanes.[24] According to Hesiod’s Theogony, Echidna and Typhon bore “fierce offspring,” including Orthrus, the two-headed dog who guarded the Cattle of Geryon, and second Cerberus, the multi-headed dog who guarded the gates of Hades who was captured by Hercules, and third the Lernaean Hydra, the many-headed serpent who, when one of its heads was cut off, grew two more. In this Fabulae, the Latin author Hyginus (c. 64 BC – 17 AD) to the list offspring of Echidna by Typhon adds Gorgon, the mother of Medusa, the Colchian dragon that guarded the Golden Fleece, and Scylla. According to Hesiod, Orthrus’ offspring included the Sphinx, a monster with the head of a woman and the body of a winged lion, and the Nemean lion, killed by Heracles.

Herodotus reported a legend told by the Pontic Greeks featuring Scythes, the first king of the Scythians, as a child of Hercules and Echidna. Hercules lost his horses in Scythia and “found in a cave a creature of double form that was half maiden and half serpent; above the buttocks she was a woman, below them a snake.”[25] She promised to return his horses only if he had intercourse with her. He did so and she bore him three sons: Gelonus, whose ancestors settled in norther Scythia; Agathyrsus, who settled in the area of Transylvania, and Scythes who became the ancestor of the Scythians.

The Scythians, also known as Scyth, Saka, Sakae, Sai, Iskuzai, or Askuzai, were Eurasian nomads, probably mostly using Eastern Iranian languages, who were mentioned by the literate peoples to their south as inhabiting large areas of the western and central Eurasian Steppe from about the ninth century BC to the fourth century AD. The Scythians first appear in Assyrian annals as Ishkuzai, related to the modern term “Ashkenazi,” from Ashkenaz, who according to the Bible was the son of Magog’s brother Gomer.[26] The most significant Scythian tribes mentioned in the Greek sources resided north of the Caucasus mountains, at the basin of the Don river, north of the Crimea and east of the Ukraine in Southern Russia. From there they invaded Armenia and Cappadocia to become allies of the early Mede rulers.

Possible migrations of the Lost Tribes of Israel

In 512 BC, when King Darius the Great of Persia attacked the Scythians, he allegedly penetrated into their land after crossing the Danube. During the fifth to third centuries BC, the Scythians evidently prospered. When Herodotus wrote his Histories in the fifth century BC, Greeks distinguished Scythia Minor, in present-day Romania and Bulgaria, from a Greater Scythia that extended eastwards from the Danube River, across the steppes of today’s East Ukraine to the lower Don basin. Philip II of Macedon took military action against the Scythians in 339 BC. In 329 BC Philip’s son, Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BC), came into conflict with the Scythians at the Battle of Jaxartes, now known as the Syr Darya River. The site of the battle straddles the modern borders of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, just south-west of the ancient city of Tashkent (the modern capital of Uzbekistan) and north-east of Khujand (a city in Tajikistan).

The Alexander Romance

A coin depicting Alexander the Great, conqueror of Egypt, with Horns of Amon on his head

Having captured Babylon, which he had planned to make his imperial capital, Alexander acquired full control of the enormous Persian Empire. Alexander then pressed on, turned northward to Afghanistan, Bactria, Sogdiana, and the Hindu Kush mountains, and finally conquered the Northern region of India in 326 BC. Alexander founded several cities in his new territories in the areas of the Amu Darya and Bactria, and Greek settlements further extended to the Khyber Pass, Gandhara and the Punjab. In 323 BC, on the eve of an expedition to conquer Arabia, Alexander fell ill and died at the age of thirty-three. After his death, his generals broke up the empire, establishing realms of their own. Antigonus governed Macedonia and Greece. Phoenicia, fell to Ptolemy Sotor who established himself as satrap in Egypt and eventually adopted the title of king in 304 BC, inaugurating the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt for three hundred years. Seleucus became satrap of Babylonia, founding the Seleucid empire, that at its greatest extent included central Anatolia, Persia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and what is now Kuwait, Afghanistan, and parts of Pakistan and Turkmenistan.

The Seleucid empire’s geographic span, from the Aegean Sea to Afghanistan, brought together a multitude of races: Greeks, Persians, Medes, Jews and Indians. Its rulers were in the position of having a governing interest to implement a policy of racial unity initiated by Alexander. By 313 BC, Hellenic ideas—disseminated by the conquering Macedonian army’s hired philosophers and historians, retired officers, and married inter-racial couples—had begun their almost 250-year expansion into the Near East, Middle East, and Central Asian cultures. It was the empire's governmental framework to rule by establishing hundreds of cities for trade and occupational purposes. Many cities began, or were induced, to adopt Hellenized philosophic thought, religious sentiments, and politics. Synthesizing Hellenic with native cultures and intellectual trends met with varying degrees of success—resulting in times of simultaneous peace and rebellion in various parts of the empire.

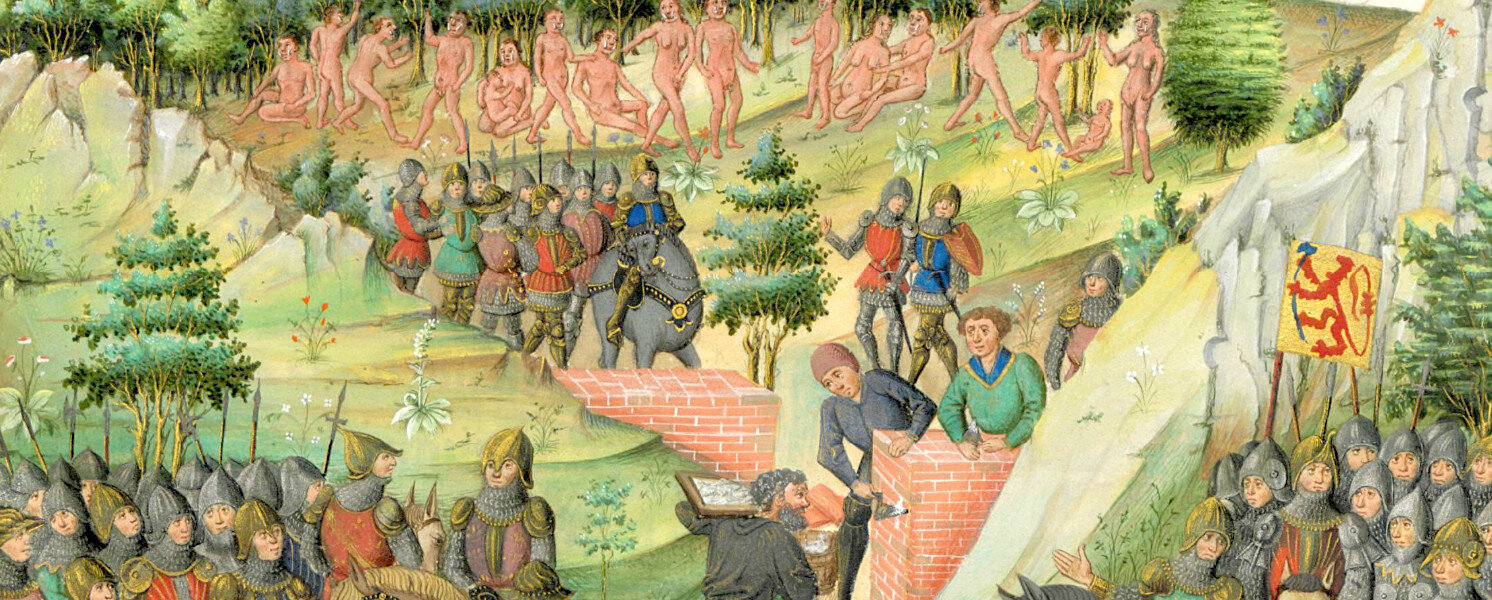

In the Alexander Romance, composed in the Greek language before 338 AD, an account parallels a similar one in the Quran, where Alexander the Great chases his enemies to a pass between two peaks in the Caucasus. With the aid of God, Alexander and his men close the narrow pass in the Caucasus by constructing a huge wall of steel, keeping the barbarous Gog and Magog from pillaging the peaceful southern lands. The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a travel memoir which first circulated between 1357 and 1371, explicitly associates the nations confined by Alexander with the Ten Lost Tribes. The Ten Lost Tribes had come to be identified with Gog and Magog sometime around the twelfth century, and possibly the first to do so was Petrus Comestor in his Historica Scholastica (c. 1169–1173).

The accounts of the Alexander Romance are reflected in the enigmatic figure mentioned in the Quran, named Dhul-Qarnayn, literally “He of the Two Horns,” who some Muslim and other commentators have identified with Alexander the Great.[27] Likewise, Alexander was already known as “the two-horned one” in early legends.[28] The description may ultimately derive from the image of Alexander wearing the horns of the ram-god Zeus-Ammon, as popularized on coins throughout the Hellenistic Near East.[29] Alexander has also been identified, since ancient times, with the horned figure in the Bible who overthrows the kings of Media and Persia. In the prophecy of Daniel 8, Daniel has a vision of a ram with two long horns, and verse 20 explains that, “The ram which thou sawest having two horns are the kings of Media and Persia.” According to Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews, when Alexander met the Jewish high priest Jaddua in Jerusalem and the assembled Jews, he was shown the book of Daniel, and he believed himself to be the fulfilment of that prophecy and was pleased.[30] This identification continued to be accepted by the Church Fathers.[31]

As pointed out by Peter G. Bietenholz, by combining two passages in Josephus’ Jewish Antiquities with one in his Jewish War, we learn that Magog, a son of Japheth, was the founding father of the Magogai, commonly known as the Scythians. Living in the regions of the Tanais [Don River] and the Maotic marshes (Sea of Azov), the Scythians one day defeated one of the generals of Alexander the Great.[32] To prevent further advances, Alexander locked them up in their territory by blocking their passage through the Caucasus with iron gates. In Roman times, when a Scythian tribe, the Alans, were planning a further expedition to plunder Armenia, Media and the regions beyond, they allied themselves with Artabanus, King of Hyrcania (465 – 464 BC).[33]

Alexander the Great’s army build a wall around the people of Gog and Magog. 15th c., France.

Around the beginning of the Christian era, a version of the story composed in Jewish circles in Alexandria, appears to have added elaborate details to the narrative, which inspired both Pseudo-Callisthenes and Pseudo-Methodius, the source of the medieval tradition in the West.[34] The Alexander Romance is any of several collections of legends recounting the legendary exploits of Alexander the Great. The earliest version is in Greek, produced in the third century AD. Several late versions attribute the work to Alexander’s court historian Callisthenes, but the actual historical figure died before Alexander. Therefore, the unknown author is referred to as Pseudo-Callisthenes. The text was recast into various versions throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages, including the languages of Syriac, Arabic, Persian, Ethiopic, Hebrew, Turkish, and Middle Mongolian.

Dhul-Qarnayn, with the help of some jinn, building the Iron Wall to keep the barbarian Gog and Magog from civilized peoples. (16th-century Persian miniature)

In addition to the Alexander Romance of Pseudo-Callisthenes, the Syriac version also includes a short appendix now known as the Syriac Alexander Legend. This original Syriac text was written in north Mesopotamia around 629-630 AD, a little more than a decade after the revelation of the story of Dhul-Qarnayn, but before the Muslim conquest of Syria and the resulting surrender of Jerusalem in 636 AD.[35] It contains additional motifs not found in the earliest Greek version of the Romance, including the episode where Alexander builds a wall against Gog and Magog. In Asia, the development of the Romance was profoundly affected by the so-called Christian Legend Concerning Alexander, an apocalyptic work not known in the West, until a Syriac version was published only in recent times.[36]

In the account found in chapter 18, “The Cave,” of the Quran, Dhul-Qarnayn is not identified with Alexander, but the stories are almost identical. This chapter was revealed to Muhammad when his tribe, the Quraysh, sent two men to discover if the Jews could advise them on whether Muhammad was a true prophet of God. The rabbis told them to ask Muhammad about three things, one of them about a man who travelled and reached the east and the west of the earth, and what was his story.[37] According to Islamic tradition, the verses were revealed in a period that would have preceded the compilation of the Syriac Alexander Legend. Nevertheless, as pointed out by Kevin Van Bladel, almost every element in the Quranic version of the story tale is also recounted in the Syriac Alexander Legend, but in a more detail where it is quite a bit longer. Each of the five parts of the Quranic account has a match in the Syriac text, and is presented in precisely the same order.[38]

Dhul-Qarnayn is described as a great and righteous ruler who built the wall of iron and copper that keeps Gog and Magog from attacking the people whom he met on his journey to the east, “the rising-place of the sun.”[39] There he meets a people for whom God did not provide protection from the Sun, a possible reference to the white-skinned early Caucasians. According to Islamic traditions, unable to pass the wall, Gog and Magog have been digging below ground ever since, and will emerge at the time of the return of the Messiah Jesus, to afflict the earth, but Jesus will pray to God to eradicate them.[40] The wall has been frequently identified with the Caspian Gates of Derbent, Russia, and with the Pass of Darial, on the border between Russia and Georgia. An alternative theory links it to the Great Wall of Gorgan, also known as “Alexander’s Wall,” on the south-eastern shore of the Caspian Sea, 180 km of which is still preserved to this day. In the Muslim world, several expeditions were undertaken in an attempt to find and study Alexanders’ wall. An early expedition to Derbent was sent by the prophet Muhammad’s successor Caliph Umar (586–644 AD), during the Arab conquest of Armenia, where they heard about the wall from the conquered Armenian Christians. The expedition was recorded by Al-Tabarani (873 – 970 AD), Ibn Kathir (1301 – 1373 AD), and by the Muslim geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi (1179 – 1229 AD). Finally, elsewhere the Quran it is mentioned that the end of the world would be signaled by the release of Gog and Magog from behind the wall, and other apocalyptic writings report that their destruction by God in a single night would usher in the Day of Judgement.[41]

Brahmins

Alexander the Great meets the gymnosophists of India

The first three levels of the Hindu caste system correspond exactly to Plato three classes of workers, soldiers and philosopher-kings

The Bene Israel (“Sons of Israel”), are a historic community of Jews who have been suggested as descendants of one of the Lost Tribes of Israel who had settled there centuries ago.[42] Genetic analysis shows that the Bene Israel of India cluster with the indigenous populations of western India, but do have a clear paternal link to the populations of the Levant.[43] A recent more detailed study on Indian Jews has reported that the paternal ancestry of Indian Jews is composed of Middle East specific haplogroups as well as common South Asian haplogroups, including R1a.[44]

The Greeks were aware of a class of Indian philosophers whom they referred to as Gymnosophists. In Of Education, Clearchus of Soli, a Greek philosopher of the fourth and third century BC, claimed that “the gymnosophists are descendants of the Magi.” In a text quoted by Josephus, Clearchus reported a dialogue with Aristotle who stated that the Hebrews were descendants of the Indian philosophers:

Jews are derived from the Indian philosophers; they are named by the Indians Calami, and by the Syrians Judaei, and took their name from the country they inhabit, which is called Judea; but for the name of their city, it is a very awkward one, for they call it Jerusalem.[45]

R1a is also found among another people who claimed descent from Alexander the Great, the Kalasha or Kalash of Pakistan.[46] The Kalash people’s reputed connection to Alexander the Great is the basis of the famous Rudyard Kipling story The Man Who Would Be King. There is a also a tradition among the Pashtuns, a people native to Afghanistan and Pakistan, of being descended from the exiled lost tribes of Israel as well.[47] According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, the theory of Pashtun descent from Israelites is traced to Maghzan-e-Afghani, a history compiled for Khan-e-Jehan Lodhi in the sixteenth century. In his universal history Mirat-ul-Alam (“The Mirror of the World”), Bukhtawar Khan (d. 1685) describes the journeys of the Pashtuns from the Holy Land to Ghor, Ghazni, and Kabul. The Yusufzai, literally “The descendants of Yusuf,” is a tribe of Pashtun people found in Pakistan, and in some eastern parts of Afghanistan. Pakistani activist for female education and the youngest Nobel Prize laureate, Malala Yousafzai also belongs to the family.

Color-based caste-system of India

South Asian populations have the highest concentrations of R1a1a, with the highest concentrations being represented among the West Bengal Brahmin caste of India.[48] The Brahmins were the highest ranking of the four social classes of India’s caste system, a class system based on birth, which corresponds almost exactly to Plato’s class system in his Republic. Plato divides his just society into three classes: the guardians, the warriors and the producers. The Indian castes or “Varnas,” include Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (ruling and military), Vaishyas (merchants and farmers), Shudras (peasants) and Dalits (untouchables). India’s class system is unique, as no other major culture historically used a fully hereditary class system that was as defined and tied to their faith as the Indians.

The system is considered part of the trifunctional hypothesis of prehistoric Proto-Indo-European, reflected in the existence of three classes or castes—priests, warriors, and commoners. The thesis is primarily associated with the French mythographer Georges Dumézil, who proposed it in 1929. A 2001 study found that the genetic affinity of Indians to Europeans is proportionate to caste rank, the upper castes being most similar to Europeans, whereas lower castes are more like Asians. The researchers believe that the Indo-European speakers entered India from the Northwest, mixing with or displacing the proto-Dravidian speakers, and may have established a caste system with themselves primarily in higher castes.[49]

However, despite attempts to attribute its introduction by the ancient “Aryans,” the Indian caste system was a later development. The Mahabharata, whose final version is estimated to have been completed by the end of the fourth century, discusses the varna system in section 12.181, presenting two models. The first model describes varna as a color-based system, through a character named Bhrigu, “Brahmins varna was white, Kshatriyas was red, Vaishyas was yellow, and the Shudras’ black.” Many of the restrictions imposed upon the Brahmins are outlined in the Manusmriti, also known as the Laws of Manu, one of the first Sanskrit texts to have been translated into English in 1776, by Sir William Jones, and which was used to formulate the Hindu law by the British colonial government. In accordance with their attempts to construct an Aryan pedigree of the Indo-Europeans, Jones and Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel assigned Manusmriti to the period of around 1250 BCE and 1000 BCE respectively. However, more recent scholarship has shifted the chronology of the text to between 200 BC and 200 AD.[50] The origin myth of the Chitpavan Brahmins—a Hindu Maharashtrian Brahmin community inhabiting Konkan, the coastal region of the state of Maharashtra in India—as a shipwrecked people, is similar to the mythological story of the Bene Israel Jews of the Raigad district, who claim to be descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel.[51] The Bene Israel claim that Chitpavans are also of Jewish origin.[52]

Until the twenty-first century, India had the largest number of Jews of any country east of Iran. According to Nathan Katz in “Contacts Between Jewish and Indo-Tibetan Civilizations Through the Ages: Some Explorations,” in the West, our numerical notation system is incorrectly referred to as “Arabic numerals” when, in fact, they were brought from India via the Middle East and into Europe by Jews.[53] Many Arab travelers record a Jewish presence in India. The ninth century geographer Abu Said al-Hassan mentioned Jewish communities in India and Ceylon. The greatest Muslim traveler al-Biruni, of the tenth and eleventh centuries, left the most extensive account. He held that the people of Kashmir were descendants of Jews, and that there was a large Jewish community there. Other great Muslim writers also discussed Indo-Jewish links, including al-Idrisi of the twelfth century and especially ibn Battuta of the fourteenth century.

Gymnosophists

Eastern icon of Thomas the Apostle

Some early Christians were aware of Buddhism which was practiced in both the Greek and Roman Empires in the pre-Christian period. The cultural amalgam of ancient Greek culture and Buddhism is referred to as Greco-Buddhism, which developed between the fourth century BC and the fifth century AD in Bactria and the Indian subcontinent, corresponding to the territories of modern-day Tajikistan, Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan. It was a cultural consequence of a long chain of interactions begun by Greek forays into India from the time of Alexander the Great. Alexander had established several cities in Bactria (Ai-Khanoum, Bagram) and an administration that was to last more than two centuries under the Seleucid Empire and the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, the whole time in direct contact with Indian territory, and extended during the flourishing of the Greek-inspired Kushan Empire.

The Macedonian satraps were then conquered by the Mauryan Empire, under the reign of Chandragupta Maurya. The Mauryan Emperor Ashoka would convert to Buddhism and spread the religious philosophy throughout his domain, as recorded in the Edicts of Ashoka. Following the collapse of the Mauryan Empire, Greco-Buddhism continued to flourish under the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, Indo-Greek Kingdoms, and Kushan Empire. The Greco-Bactrians maintained a strong Hellenistic culture at the door of India during the rule of the Maurya Empire in India, as exemplified by the archaeological site of Ai-Khanoum, in northern Afghanistan. When the Maurya Empire was toppled by the Shunga Empire around 180 BC, the Greco-Bactrians expanded into India, where they established the Indo-Greek Kingdom, under which Buddhism was able to flourish. Menander I Soter (reigned c.165/155 – 130 BC) was a Greco-Bactrian and later Indo-Greek King who administered a large territory in the Northwestern regions of the Indian Subcontinent from his capital at Sagala. Menander is noted for having become a patron and convert to Greco-Buddhism and is widely regarded as the greatest of the Indo-Greek kings.[57]

Buddhist missionaries were sent by Emperor Ashoka (304 – 232 BCE) of India to Syria, Egypt and Greece beginning in 250 BC. Elmar R. Gruber and Holger Kersten have proposed that the Therapeutae—the Egyptian sect reported of by Philo of Alexandria and who were related to the Essenes—may even have been descendants of Ashoka’s emissaries.[58] Some modern historians have suggested that the name for the Therapeutae was possibly a deformation of the Pāli word Theravāda, a form of Buddhism.”[59] Buddhist gravestones from the Ptolemaic period have been found in Alexandria decorated with depictions of the dharma wheel.[60]

The occult schools of Alexandria had long known of the ascetic philosophers of India as “gymnosophists.” The Gospel of Thomas, one of the Gnostic Gospels found near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, is named for the Apostle Thomas, who is traditionally believed by Christians in Kerala, on the Malabar Coast, to have spread Christianity among the Jews there. Edward Conze, a British scholar of Buddhism, pointed out that “Buddhists were in contact with the Thomas Christians [Christians who knew and used the Gospel of Thomas] in south India.”[61] Gnostic scholar Elaine Pagels mentioned that, “Trade routes between the Greco-Roman world and the Far East were opening up at the time when Gnosticism flourished (A.D. 80-200); for generations, Buddhist missionaries had been proselytizing in Alexandria.”[62] Pagels also reports that Hippolytus, a Christian scholar in Rome, wrote about the Indian Brahmins’ “heresy.”[63]

According to his biographer Philostratus, Apollonius of Tyana (c. 15 – c. 100 AD) was also said to have travelled to India, and was welcomed by its kings, and was, with Damis, his companion, for four months the guest of its Brahmans. Apollonius had met the Gymnosophists of India before his arrival in Egypt, and repeatedly compared the Ethiopian Gymnosophists with them. He regarded them to be derived from the Indians. They lived without any cottages nor houses, but had a shelter for the visitors. They did not wear any clothes and thus compared themselves to the Olympian athletes. They shared their vegetarian meal with him.[64]

Christians in Kerala, India.

There were also contacts between Gnostics and Indians. Syrian Gnostic theologian Bar Daisan described in the third century AD his exchanges with missions of holy men from India, passing through Syria on their way to Elagabalus or another Severan dynasty Roman Emperor.[65] Several scholars have pointed to the striking similarities between Gnosticism and various Indian and Buddhist traditions. As noted by Stepen A. Kent, the Tibetan Buddhist scholar Giuseppe Tucci acknowledged the “surprising simultaneity” between “the inwardly experienced psychological drama” of both Tantra and Gnosticism. Edward Conze, the noted Buddhist scholar, identified the “eight basic similarities between Gnosticism and Mahayana Buddhism” and further noted an additional twenty-three possible similarities. Coptic scholar Jean Doresse referred to possible “discoveries” that could be found between Gnosticism and “certain texts of Indian literature of the same period.[66]

In his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius, the third century Christian bishop of Caesarea, wrote of Jewish settlements in India existing as early as the first century AD. He discussed an Alexandrian Stoic philosopher by the name of Pantaenus, who “was sent as far India” to evangelize “the heathen in the East.” Pantaenus, known as the tutor to Clement of Alexandria and Origen, made his journey shortly after the reign of Marcus Aurelius, which would place him in India around 181 AD. Saint Jerome (c. 342 – c. 347 – 420) mentions the birth of the Buddha, who he says “was born from the side of a virgin.” The early church father Clement of Alexandria (d. 215 AD) was also aware of Buddha, writing in his Stromata: “The Indian gymnosophists are also in the number, and the other barbarian philosophers. And of these there are two classes, some of them called Sarmanæ and others Brahmins.”[67]

Arrival of the Jewish pilgrims at Cochin (71 AD)

In the ninth century, ibn Wahab wrote about the Cochin Jews (also known as Malabar Jews), the Jewish community of Cranganore, near Kochi (Cochin), on the Malabar Coast in southwest India. Comprising one of three major distinct Jewish communities in India, the Cochin Jews are called Cochinim in Hebrew, though the majority now live in Israel. Their roots are claimed to date back to the time of King Solomon.[68] They settled in the Kingdom of Cochin, now part of the state of Kerala. According to The History of the works of the learned (1699) published in England, a letter in Hebrew was brought from India, in which the Cochin Jews recounted the story of their ancestors’ arrival in Malabar after the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans.[69] According to Josephus, during the siege of Masada by Roman troops at the end of the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73), which resulted in the destruction of the Second Temple, the Sicarii martyrs who committed mass suicide were inspired by the speeches of their leader Eleazar, to follow the example of the Indian philosophers, an example of fearlessness based on their firm belief in the eternity of the soul. According to the letter, the king who reigned in India at the time granted them a Province called Shingly (Cranganore), near the city of Cochin (Kochi). [70]

During the twelfth century, a number of Jewish travelers visited India and wrote about Jewish life there. The most influential was Benjamin of Tudela, who left extensive descriptions of the Jews of southwest India. Speaking of Kollam (Quilon) on the Malabar Coast, he wrote in his Itinerary: “…throughout the island, including all the towns thereof, live several thousand Israelites. The inhabitants are all black, and the Jews also. The latter are good and benevolent. They know the law of Moses and the prophets, and to a small extent the Talmud and Halacha.”[71] It was during the same century that Maimonides wrote that his Mishneh Torah was studied in India. A quatrain by the fourteenth-century Rabbi Nissim of Spain expresses his pleasure at finding a Jewish king at Shingly, just north of Cochi.[72]

Trade routes of the Radhanite Jewish merchants.

The ancient spice trade followed land and sea routes between the Middle East and South India. The famous silk routes, which may date from as early as the second century AD, linked Europe with China. Muslim travelers’ diaries from the ninth and tenth century AD testify to the prominent role of Jews in both these trades. Ibn Khordadbeh, an official of the Baghdad caliphate, in his Book of Roads and Kingdoms (ca. 870), described the commercial activities of the Radhanites, Jewish merchants in the trans-Eurasian trade network. Radhanites, who were based in northern Spain or southern France, maintained a number of distinct trading routes, including one that traversed Central Europe from Spain through France, Germany, Eastern Europe, the kingdoms of the Khazars, Asia, and thence into China. Another ran along the southern coast of Europe from Spain through Burgundy, Italy, the Balkans, Greece, Turkey, Baghdad, India, and around Indonesia to China. Another traversed Spain, North Africa, Egypt, Arabia, Yemen, and India, linking up to China.[73]

Tibetan Buddhism

Yungdrung is a left facing swastika, a sacred symbol of Bon religion.

As Nathan Katz noted, there were Jews in the northwestern region of what is now China at least from the eighth century AD.[74] Pan Guangdan (aka Quentin Pan), a Chinese sociologist who specializes on the Jews, argued that a Jewish presence existed in Guangzhou (Canton), Ganpu and Hangzhou during the late Tang dynasty, or the ninth century AD, as well as medieval communities in Ningbo, Beijing, Quanzhou, Ningxia, Yangzhou and Nanjing, and also in the famous community at Kaifeng, during medieval times. Tibet, then, suggests Katz, “was virtually encircled with Jewish settlements, however small, in India, Kashmir, Turkestan, and China. It appears that Tibet at one time controlled a city, Khotan, a Jewish community, during the eighth century.”[75]

Katz further suggests that there seems to be a further religious link as well, between Jewish messianism and the Tibetan Kalachakra system. In the Western mind, Tantra is most commonly associated with sex, and often mistaken for the Kama Sutra. Tantra is a style of religious ritual and meditation recognized by scholars to have arisen in medieval India no later than the fifth century AD, after which, it influenced Hindu traditions and spread with Buddhism to East Asia and Southeast Asia. Tantric sex, or sexual yoga, refers to a range of practices in Hindu and Buddhism in a ritualized context, often associated with antinomian tendencies. While taboo-breaking elements are symbolic for “right-hand path” Tantra (Dakshinachara), they are practiced literally by “left-hand path” Tantra (Vamachara). Vamachara is a mode of worship or sadhana (spiritual practice) that is considered heretical according to Vedic standards. Secret rituals may involve feasts of otherwise prohibited substances, sex, cemeteries, and defecation, urination and vomiting. Most important is the ritual sexual union known as Maithuna, mirroring the “sacred marriage” of Gnosticism, during which the man and the woman become divine: she is the goddess Shakti, and he the god Shiva. In particular, semen and menstrual blood produced through ritual sex the guru and his consort have been viewed as “power substances” and even ingested ritualistically.[76]

Tibetan painting depicting Indian Buddhist Mahasiddhas and yoginis practicing Karmamudra, a Vajrayana Buddhist technique which makes use of sexual union with a physical or visualized consort.

The equivalent to Maithuna in Buddhist tantras is the practice of Karmamudra, a Vajrayana Buddhist technique which makes use of sexual union with a physical or visualized consort, and are generally not found in common Mahayana Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism teaches methods for achieving Buddhahood more quickly, by including in Mahayana the path of Vajrayana, where the physical practice of sexual yoga is considered necessary at the highest level for such attainment. Influenced by various heterogeneous elements and Hindu Tantra, Vajrayana came into existence in the sixth or seventh century AD. The Vajrayana was then followed by the new Tantric cults of Sahajayana and Kalachakra. In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, it is claimed that the historical Buddha taught Tantra, but that since these were “secret” teachings, transmitted only from guru to disciple, they were generally written down long after his other teachings. However, historians argue that assigning these teachings to the Buddha is “patently absurd.”[77]

Tibetan Buddhism’s complex cosmology is the basis for a superstitious and highly ritualized set of beliefs that evolved from an amalgam of Buddhism, Hindu Tantra and the pre-Buddhist shamanistic religion of Bön. Bön then became an unorthodox form of Buddhism that arose in Tibet during the tenth and eleventh centuries.[78] Tibetan culture is proliferated with a variety of spirits and demons that, according to the principles of apotropaic magic, must be propitiated by various rituals and offerings. As explained Lydia Aran, “Such shamanic techniques are found in many societies, but Tibet is the only known literate society in which they form a central rather than marginal element.” Therefore, according to Aran, in “Inventing Tibet”:

In shamanic Buddhism, the central figure is not a monk but the tantric lama, who need not be celibate or have formal monastic training but whose proficiency in ritual and yogic practice generates in him shamanic—i.e., “magical”—power… The nexus between the pursuit of enlightenment by a small minority and the demand for shamanic services by the great majority is the hallmark of Tibetan Buddhism.[79]

Tibetan Buddhists generally referred to “madmen” as Mahasiddha, a term for someone who embodies and cultivates the “siddhi of perfection.”[80] A siddha is an individual who, through the practice of sādhanā, attains the realization of siddhis, psychic and spiritual abilities and powers. Mahasiddhas were practitioners of yoga and tantra, or tantrikas, whose historical influence reached mythic proportions throughout the Indian subcontinent and the Himalayas, as codified in their songs of realization, or namtars, many of which have been preserved in the Tibetan Buddhist canon. Samadhi, in Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness or trance, attained by the practice of dhyana. In Buddhism, Samadhi is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path.

Yeshe Tsogyal (c. 757 or 777 – 817 CE), sexual consort in the practice of Karmamudra with Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche a tantric Buddhist Vajra master, who taught Vajrayana in Tibet.

While some stories depict the arrival of Buddhism in Tibet earlier, the religion was formally introduced during the Tibetan Empire, between the seventh and ninth century AD. Traditional Vajrayana sources say that the tantras and the lineage of Vajrayana were taught by Sakyamuni Buddha and other figures such as the bodhisattva Vajrapani and Padmasambhava, a tantric Buddhist Vajra master from India. Vajrayana Buddhism was initially established in Tibet in the eighth century AD when various figures like Sakyamuni and Padmasambhāva were invited by King Trisong Detsen (755 – 797 AD), who had established Buddhism as the official religion of the state. Padmasambhava, who is considered by the Tibetans as Guru Rinpoche, is also credited with building the first monastery building named Samye. Yeshe Tsogyal, considered the Mother of Tibetan Buddhism, was a member of Trisong Detsen’s court and became a student of Padmasambhava and his main Karmamudra consort.

There is evidence to show that Christianity found its way into South East and East Asian countries even before the coming of western missionaries, through the efforts of merchants and missionaries of Nestorianism, a heresy incorrectly attributed to Nestorius (d. c. 450), from Persia or India or China. In the thirteenth century, international travelers, such as Giovanni de Piano Carpini and William of Ruysbroeck, sent back reports of Buddhism to the West and noted certain similarities with Nestorianism.[81] Syncretism between Buddhism and Nestorianism was widespread along the Silk Road in Antiquity and the Middle Ages, and was especially evident in the medieval Church of the East in China. This was especially evident in the Jingjiao Documents, Nestorian documents also known as the Jesus Sutras, a collection of Chinese language texts connected with the seventh-century mission of Alopen, a Church of the East bishop from Sassanian Mesopotamia.[82] The manuscripts date from between 635 AD, the year of Alopen’s arrival in China, and around 1000 AD, when the cave near Dunhuang in which the documents were discovered was sealed. A surprising example was found among these documents from a Book of Divination adapted to Buddhism, which hint at Gnostic influence:

Man, your ally is the god called “Jesus Messiah”. He acts as Vajrapani and Sri Sakyamuni. When the gates of the seven levels of heaven have opened, you will accomplish the yoga that you will receive from the judge at the right hand of God. Because of this, do whatever you wish without shame, fear or apprehension. You will become a conqueror, and there will be no demons or obstructing spirits. Whoever casts this lot (mo), it will be very good.[83]

The strongest evidence for the involvement of Christian missionaries in early Tibet comes in the letters of Timothy I, who was Patriarch of the Nestorian Church between 780 and 823 AD, overlapping with the reigns of three of Tibet’s great Buddhist emperors, Trisong Detsen, Senaleg and Ralpachen. Timothy I is known to have consecrated metropolitans for Damascus, Armenia, Dailam and Gilan in Azerbaijan, Rai in Tabaristan, Sarbaz in Segestan, for the Turks of Central Asia, and for China and possibly Tibet. According to Aziz S. Atiya, an example of Nestorianism influence is the survival of its ritual in a modified form in the Lamaism of Tibet, including the use of holy water, incense and vestments of a similar to Nestorian practices.[84] Nestorian crosses have been found in several places such as Anuradhapura, which are very similar in style to those in Persia, China at Sian-fu-stele and to those in Tibet and Armenia.[85]

Al-Biruni claimed that the Persian prophet Mani (216 – 274 AD) also went to Tibet, and that “most of” of the country adhered to his religion.[86] Mani is the founder of a religion known as Manichaeism, formed from Mesopotamian religious movements and Gnosticism, and which revered Mani as the final prophet after Zoroaster, Gautama Buddha, and Jesus. Early third and fourth century Christian writers such as Hippolytus of Rome and Epiphanius wrote about a Scythianus, who according to H.G. Rawlinson, was the first Alexandrian to visit India, around 50 AD.[87] Scythianus acquainted himself with Indian philosophy and learned, according to Epiphanius, that “all things comes from two roots or two principles.” Scythianus’ pupil Terebinthus presented himself as a “Buddha” and went first to Palestine and Judaea, “becoming known and condemned,” and ultimately settled in Babylon, where he transmitted his teachings to Mani. Manichaeism thrived between the third and seventh centuries AD, and at its height was one of the most widespread religions in the world. Manichaean churches and scriptures existed as far east as China and as far west as the Roman Empire. It was briefly the main rival to Christianity before the spread of Islam. Manichaeism spread to Tibet during the Tibetan Empire. However, in the Criteria of the Authentic Scriptures, a text attributed to Trisong Detsen, the author attacks Manichaeism by accusing Mani of being a heretic who took ideas from all faiths and blended them together into a perverted form.[88]

Kalachakra Tantra

The Kalachakra, meaning “wheel of time” or “time cycles,” is an encyclopedic collection of Vajrayana Buddhist knowledge. The Kalachakra Tantra, which developed in the tenth century AD, is farthest removed from the earlier Buddhist traditions, and incorporates concepts of messianism and astrology not present elsewhere in Buddhist literature.[89] It depicts a mythic reality whereby cosmic and historical events correspond to processes in the bodies of individuals. These teachings are meant to lead to a transformation of one’s body and mind into perfect Buddhahood through various yogic methods. The Kalachakra Tantra contains passages that refer to a mystical kingdom called “Shambhala,” said to be located near mount Kailasa and its capital is Kalapa, and which is ruled by a line of Buddhist kings that preserve the Kalachakra teachings. It also mentions how this kingdom comes into conflict with barbarian invaders called mleccha, which most scholars agree refers to Muslims and the Muslim invasions of India.[90]

The Kalachakra Tantra is considered the “highest of all Vajrayana ways,” and “the pinnacle of all Buddhist systems.”[91] The chains of the initiation, which can supposedly be traced back to the Buddha, are known as “transmission lines,” which proceed orally from guru or lama to his pupil (sadhaka). However, since it belongs to the highest secret teachings, it is only permitted be practiced by an elite few. Kalachakra Tantra is divided in fifteen stages, seven of which are public and ceremonial, while the remaining eight contain practices of sexual yoga and are kept secret, being reserved for a handful of initiates. Among the eight higher stages, for the first four the apprentice must bring the lama a young woman of ten, twelve, sixteen, or twenty years of age as Karmamudra. Without a living karma mudra enlightenment cannot, at least according to the original text, be attained in this lifetime.[92]

In the highest magical initiations of the Kalachakra Tantra, what are known as “unclean substances” are employed, and involve the consumption of five types of meat, including human flesh, and the five “nectars,” such as blood, semen and menses.[93] As in Indian alchemy, menstrual blood is also utilized as a ritual substance, as it is part of the red-white mixture mix of male and female sexual fluids (sukra) the yogi must consume. It is also possible to recover the sukra out of her body in a vase or human skull (kapala) in order to consume it. In contrast to his guru, the sadhaka may under no circumstances release his semen during the ritual. In Tibetan Buddhism, as usual in Tantra, the male must refrain from ejaculating in order to attain enlightenment. Emission of semen is reserved only to those who are already enlightened. For the pupil, hell is promised to him if he fails to refrain from ejaculation. However, he can undo his mistake by catching the sukra from out of the vagina in a vessel and then drinking it.[94]

The final four-stage ritual, known as Ganachakra, is the deepest secret of the Kalachakra Tantras, but is also known in the other Highest Tantras. After the pupil has handed the women over to his master, he is given back one of them as a symbolic “spouse.” The guru now moves to the center of the circle (chakra) and performs a magic dance, and then copulates with Shabdavajra in the divine yoga. After he has withdrawn himself, the guru places his phallus filled with semen in the mouth of the pupil. After that, the master gives the pupil his own mudra. The master places his penis in the mouth of the pupil’s wife, and then orally stimulates his own wife’s clitoris. The guru then offers the pupil the remaining women, with whom he must have intercourse with as many of them as possible, for at least 24 minutes each.[95]

It was proposed that the Ganachakras should take place at various secret locations. The famous Tibetan historian, Buton Rinchen Drub (1290 – 1364), suggested using “one’s own house, a hidden, deserted or also agreeable location, a mountain, a cave, a thicket, the shores of a large lake, a cemetery, a temple of the mother goddess.”[96] According to the Hevajra Tantra, which is believed to have originated between the late eight or early tenth century: “These feasts must be held in cemeteries, in mountain groves or deserted places which are frequented by non-human beings. It must have nine seats which are made of parts of corpses, tiger skins or rags which come from a cemetery. In the middle can be found the master, who represents the god Hevajra, and round about the yoginis… are posted.”[97]

The ten karma mudras present during the ritual go by the name of “sacrificial goddesses.” One event in the Ganachakra is known as “sacrifice of the assembly,” in reference to the sacrifice of the women.[98] Texts by Sakya Pandita (1182 – 1251) and Buton Rinchen Drub prove that such sacrifices were really carried out.[99] Albert Grünwedel believed that the female consorts of the gurus were originally sacrificed at the Ganachakra and burned at the stake like European witches so as to then be resurrected as “dakinis,” as tantric demonesses. The sacrificial flesh of a “sevenfold born” is also offered as a sacred food at a Ganachakra. In the Vajradakinigiti, the story which provides the basis for a tantric context, several dakinis kill a sevenfold-born son of a king in order to make a sacrificial meal of his flesh and blood. Similarly, two scenes from the life of the Kalachakra master Tilopa (988 – 1069) tell of the consumption of a “sevenfold born” at a dakini feast.[100] Kalachakra remains an active tradition of Buddhist tantra in Tibetan Buddhism, and its teachings and initiations have been offered to large public audiences, most famously by the current 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso.

Attila the Hun

Mór Than's nineteenth century painting of The Feast of Attila, based on a fragment of Priscus

Also widely identified with the Scythians and Gog and Magog were the Huns, a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the fourth and sixth century AD. The contents of the Syriac Legend of Alexander, describing Alexander’s exploits in the land of the rising sun, are summarized in a brief introductory heading:

An exploit by Alexander, the son of Philip the Macedonian, how he went forth to the ends of the world, and made a gate of iron, and shut it in the face of the north wind, that the Huns might not come forth to spoil the countries: from the manuscripts in the house of the Kings of Alexandria.[101]

According to the conclusion of the Syriac Legend of Alexander, which has no corresponding part in the Quran, after he the wall built to keep out Gog and Magog, Alexander put an inscription on it containing a prophecy for events to follow his lifetime, that were given precise dates. The first announced that after 826 years, the Huns will break through the gate and plunder the lands. Then, after 940 years, God would gather together the kings and their hosts and will give a signal to break down the wall, and the armies of the Huns, Persians, and Arabs will “fall upon each other,” after which the kingdom of the Romans will enter this fray conquer them all. Already in 1890, Theodor Nöldeke calculated the dates according to the Seleucid Era, and determined that 826 years later corresponded to 514–15 AD, precisely when the Sabir Huns forced their way through the middle pass of the Caucasus into Armenia, Cappadocia and Northern Mesopotamia.[102]

And as Van Bladel has indicated, Greek and Armenian sources show that these real invasions were interpreted in apocalyptic terms and associated with Gog and Magog.[103] In his commentary on Ezekiel, St. Jerome, who was forced to leave Palestine after the onslaught of the Huns, references Jewish tradition about Gog and Magog to combine it with the messianic age of Book of Revelation. According to Jerome, the Jews “think that Gog is a Scythian nation, immense and innumerable, which extend beyond the Caucasus Mountains and the Sea of Azov, and through the Caspian Sea to India.[104] After having reigned for a thousand years, explains Jerome, Gog and Magog, who had been enclosed by Alexander the Great, will be stirred up by the devil, gather many peoples and attack Palestine to fight against the saints.[105]

By 370 AD, the Huns had arrived on the Volga, and by 430 AD they established a vast, but short-lived, dominion in Europe, conquering the Goths and many other Germanic peoples living outside of Roman borders, and causing many others to flee into Roman territory. Likewise, according to Isidore of Seville (c. 560 – 636 AD), in his History of the Kings of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi, the Goths were also descendants of Gog and Magog:

It is certain that the Goths are a very old nation. Some conjecture from the similarity of the last syllable that the origin of their name comes from Magog, son of Japheth, and they deduce this mostly from the work of the prophet Ezekiel. Formerly, however, the learned were accustomed to call them Getae rather than Gog and Magog. The interpretation of their name in our language is “tecti” (protected), which connotes strength; and with truth, for there has not been any nation in the world that has harassed Roman power so much. For these are the people who even Alexander declared should be avoided.[106]

In the late fourth century AD, the lands of the Goths were invaded from the east by the Huns. While several groups of Goths came under the domination of the Huns, others migrated further west or sought refuge within the Roman Empire. Goths who entered the Empire by crossing the Danube inflicted a devastating defeat against the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD. These Goths would become known as the Visigoths, and under their king Alaric I (c. 370 – 410 AD) they began a long migration, eventually establishing a Visigothic kingdom in Spain at Toledo. In in the fifth century, Goths under the rule of the Huns gained their independence. Known as the Ostrogoths, under their king Theodoric the Great (454 – 526 AD), they established an Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy at Ravenna. The Huns, especially under Attila (c. 406 – 453 AD), made devastating raids into the eastern part of the Roman Empire. In 451 AD, the Huns invaded Gaul, where they fought a combined army of Romans and Visigoths at the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields, and in 452 AD they invaded Italy.

Khazars

Alexander the Great’s prophecy of the invasion of Gog and Magog 940 years after his lifetime corresponded to 628–9 AD, when the Khazars invaded large parts of Armenia and Northern Mesopotamia.[107] Kevin Alan Brook, among others, has speculated that the legend of the Red Jews was actually based on a vague memory of the Khazars, descendants of the Scythians who converted to Judaism in the eighth century AD.[108] Christian of Stavelot, a ninth-century Christian monk, in Expositio in Matthaeum Evangelistam refers to the Khazars as Hunnic descendants of Gog and Magog, who had been “enclosed” by Alexander, but who had since escaped.[109] Arab traveler ibn Fadlan also reported this belief, writing around 921 AD, he recorded that “Some hold the opinion that Gog and Magog are the Khazars.”[110]

Like their Edomite ancestors, the Khazars were also red-headed, and came to be known as “Red Jews.” As outlined by Raphael and Jennifer Patai, in The Myth of the Jewish Race:

...one should remember that the Khazars were described by several contemporary authors as having a pale complexion, blue eyes, and reddish hair. Red, as distinguished from blond, hair is found in a certain percentage of East European Jews, and this, as well as the more generalized light coloring, could be a heritage of the medieval Khazar infusion.[111]

In particular, the Khazars were said to descend from the Tribe of Simeon, who had been assimilated into the Edomites. According to Eldad ha-Dani, a Jewish traveler of the ninth century, the Khazars were remnants of Simeon and Manasseh. The tribe of Zebulun, on the other hand, he explained, occupies the land extending from the province of Armenia to the River Euphrates. Likewise, one version of the Letter of King Joseph, also known as the Khazar Correspondence, reported that the Khazars had a tradition that they were descended from the Tribe of Simeon. The Cochin Scroll also maintains that the Khazars were descended from Simeon and Manasseh.

The Khazars were also sometimes ascribed Armenian origin. This is stated by the seventh-century Armenian bishop and historian Sebeos, and the fourteenth century Arab geographer Dimashqi.[112] In the past, Armenia has been connected with the biblical Ashkenaz. The Armenians referred to themselves as “the Ashkenazi nation” in their literature. According to this tradition, the genealogy in Genesis 10:3 extended to the populations west of the Volga. In Jewish usage, Ashkenaz is sometimes equated with Armenia. In addition, it sometimes covers neighboring Adiabene, and also Khazaria, the Crimea and the area to the east, the Saquliba, the territory of the Slavs and neighboring forest tribes, considered by the Arabs dependent of the Khazaria, as well as Eastern and Central Europe, and northern Asia.[113]

The Cambridge Document, discovered by Solomon Schechter in the late nineteenth century, and also known as the Schechter Letter, the Schechter Text, and the Letter of an Anonymous Khazar Jew, discusses how Jewish men fled either through or from Armenia into the Khazar kingdom in ancient times, escaping from “the yoke of the idol-worshippers.” According to the letter, after the Jews from Armenia and Persia had assimilated almost totally with the Khazars, a strong war-leader arose, named Sabriel, who succeeded in having himself named ruler of the Khazars. Sabriel, who happened to be remotely descended from the early Jewish settlers, and his wife Serakh, convinced him to adopt Judaism, in which his people followed him.[114]

At its height, the Khazarian empire covered the area of the Ukraine, southern Russia to the Caucasus, and the western portions of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan to the Aral Sea. The town of Kiev, meaning “the site at the shore,” at the Dnieper river, had been founded by the Khazars around the beginning of the eighth century AD as a trading and administrative center in the western part of the Khazarian empire. However, the Kievan Rus, a loose federation of East Slavic and Finnic peoples, led by Prince Svyatoslav I (c. 942 – 972), in a treacherous collaboration with Byzantium, succeeded in penetrating the Khazarian empire and destroying their capital Itil in 967 AD.

However, a new study published in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution by Dr. Eran Elhaik, a geneticist at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, challenged the conventional hypothesis that Ashkenazi Jews migrated east from the Rhineland during the Middle Ages. The paper, “The missing link of Jewish European ancestry: contrasting the Rhineland and the Khazarian Hypotheses,” examined data published by Doron Behar and colleagues in 2010, and argues that, “Eastern European Jews are of Judeo-Khazarian ancestry forged over many centuries in the Caucasus.” Jewish presence in the Caucasus and then Khazaria was recorded as early as the late centuries BC, and reinforced due to the increase in trade along the Silk Road, the decline of Judah during Roman times, and then the rise of Christianity and Islam. Greco-Roman and Mesopotamian Jewish migration toward Khazaria was intensified following the Khazars’ conversion to Judaism. Elhaik suggests that with the final collapse of Khazaria in the thirteenth century, many Judeo-Khazars fled to Eastern Europe and later migrated to Central Europe, mixing with the neighboring populations.

ODIn

Several Medieval rabbis and Jewish Torah scholars began to locate the Ten Lost Tribes, but the location greatly varied. Maimonides wrote: “…I believe the Ten Tribes to be in various parts of Europe.”[115] Moses ben Isaac Edrehi (1774–1842), a Moroccan-born rabbi and Kabbalist, also believed the Lost Tribes of Israel were located in Europe, writing in his Historical Account Of The Ten Tribes (1836):

…Orteleus, that great geographer, giving the description of Tartary, notices the kingdom of Arsareth, where the Ten Tribes, retiring, succeeded [other] Scythian inhabitants, and took the name Gauther [Goths], because they were very jealous for the glory of God. In another place, he found the Naphtalites, who had their hordes there. He also discovered the tribe of Dan in the north, which has preserved its name. …They further add, that the remains of ancient Israel were more numerous here than in Muscovy and Polan—from which it was concluded, that their habitation was fixed in Tartary [ie Scythia] from whence they passed into neighbouring places… it is no wonder to find the Ten Tribes dispersed there; since it was no great way to go from Assyria, whither they were transplanted, having only Armenia betwixt them.[116]

In the Fourth Book of Ezra, the Ten Tribes were said to have been carried by Hosea in the eighth century BC to the Euphrates, at the narrow passages of the river. From there they went on a journey of a year and a half to a place called “Arzareth,” referring to the Araxes, a river that borders Armenia, Iran and Azerbaijan. The Araxes river is related to the legend of Sambatyon, which according to rabbinic literature, is the river beyond which the Lost Tribes were exiled, observing the laws of Moses, until the time of the restoration. The river rages with rapids and throws up stones six days a week, but stops flowing every Sabbath, the day Jews are not allowed to travel. According to the twelfth century Arab historian Muhammad al-Idrisi, who lived in Palermo, at the court of King Roger II of Sicily, the city of Sarmel (Sarkel-on-the-Don) was situated on the River Al-Sabt (Sambat), which is the River Don. The name for Kiev, as given by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905 – 959), is also Sambatas.[117]

Arzareth or Arsareth is likely the same as Asgard, the legendary home of the Scandinavians and Saxons. Some etymologies proposed that the word Scythians, from “Sacae,” in turn is derived from “Isaac Sons” or “Sons of Isaac.”[118] As noted in the Jewish Encyclopedia, “the identification of the Sacae, or Scythians, with the Ten Tribes because they appear in history at the same time, and very nearly in the same place, as the Israelites removed by Shalmaneser, is one of the chief supports of the theory which identifies the English people, and indeed the whole Teutonic race, with the Ten Tribes.”[119] Strabo asserts that the most ancient Greek historians knew the Sacaea as a people who lived beyond the Caspian Sea. Ptolemy finds the Saxons in a race of Scythians, called Sakai, who came from Media.[120] Pliny said: “The Sakai were among the most distinguished people of Scythia, who settled in Armenia, and were called Sacae-Sani.”[121] Albinus, the learned tutor of Charlemagne, maintained that: “The Saxons were descended from the ancient Sacae of Asia.”[122] A tradition that the Saxons are descended from the Sacae has also been recorded by both Camden in his Britannia (1607) and John Milton in his History of Britain (1670). Camden agreed with the opinion that “the Saxons descended from the Sacae, the most considerable people of Asia, and to be so called quasi Sacasones, q.d. Sons of the Sacae, and to have gradually overspread Europe from Scythia or Sarmatia Asiatica, with the Getae, Suevi, Daci and others.”[123]

As reported by Strabo, the Persians celebrated a festival called Sacaea, named after the Sacaea, which derived from the ancient Babylonian Zagmuk, which involved sacred the killing of the king. According to Strabo, the Sacaea as it was found in Asia Minor was celebrated alongside the worship of the Persian goddess Anaitis, the mother of Mithras. Strabo describes it as a Bacchic orgy, held at the spring equinox, at which the celebrants were disguised as Scythians, and women drank and reveled together day and night.[124] James Frazer pointed out what he considered a striking parallel to the killing of the king ritual, found among the limited monarchy of the Khazars, “where the kings were liable to be put to death either on the expiry of a set term or whenever some public calamity, such as drought, dearth, or defeat in war, seemed to indicate a failure of their natural powers. The evidence for the systematic killing of the Khazar kings, drawn from the accounts of old Arab travellers, has been collected by me elsewhere.”[125]

The Saxons, like the Vikings, claimed descent from a Hunnish leader named Uldin, later Odin, or Wotan. According to the Ynglinga Saga, written from historical sources available to the Icelander Snorri Sturluson, an Icelandic historian of the thirteenth century, Odin came from the land of Asgard, which was on the northwestern coast of the Black Sea, at the basin of the Don River. Snorri Sturluson speaks of Odin, the ancestor of the Scandinavians, making “ready to journey out of Turkland, and was accompanied by a great number of people, young folk and old, men and women; and they had with them much goods of great price.” Snorri here speaks of the land east of the Don River being known as Asaland, or Asaheim, and the chief city in that land was called Asgard, the home of Odin. The city may have been Chasgar, located in the area of the Caucasian ridge, “called by Strabo Aspargum, the Asburg, or castle of the asas.”[126]

The Icelandic sagas the Prose Edda and the Heimskringla, also compiled by Snorri Sturluson, recount that the ancestors of the Norse kings resided east of the river Don, and were led by Odin, or Uldin, who had vast holdings south of the Ural Mountains. He and his people were known as Ases, or Aesir, and after many battles, he left two brothers in charge of his domains, along a ridge of the Caucasus Mountains, called Asgard, likely Chasgar, and with his people headed north. This would have been approximately 450 AD, when Odin’s descendants were said to have founded the nations of the Danes, Swedes, and Norwegians—and in Germany, the Saxon tribes.

Thor Heyerdahl had suggested the people noted by Snorri as the Ases, or Alans, or the Aesir, may have been the Azeris of Azerbaijan.[127] In turn, the Azeris are descended from the Medes, and genetic researcher David Faux has discovered that of all the groups anywhere, only the genetic samples from the Azeri contained haplotypes that were very similar to participants tested in the Shetlands, settled by “Vikings.”[128]

Orkney Islands

Travels of the Vikings

The inhabitants of the Orkney Islands are descended from Vikings who, like the Saxons, according to various medieval legends, were in turn descended from Scythians who migrated to Northern Europe and Scandinavia. The name of Scotland was originally intended to refer to the “land of the Scythians.”[129] The idea that the Scots came from Scythia is also found in most legendary accounts and also in unedited versions of the Venerable Bede of the eighth century. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written in the ninth century AD, begins by saying that the Britons, like the Saxons, came from Armenia and the Picts of Scotland from the south of Scythia. The Pictish Chronicle of the tenth century mentions “Scithe et Gothi” (Scythians and Goths), as being the ancestors of the Picts, the people living in ancient eastern and northern Scotland.

Edmund Spenser (1552/1553 – 1599), an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, wrote: “the Chiefest [nation that settled in Ireland] I Suppose to be Scithians… which firste inhabitinge and afterwarde stretchinge themselves forthe into the lande as theire numbers increased named it all of themselues Scuttenlande which more brieflye is Called Scuttlande or Scotlande.”[130] One of Spenser’s main sources was William Camden (1551 – 1623), author of Britannia, the first chorographical survey of Britain and Ireland, who wrote: “to derive descent from a Scythian stock, cannot be thought any waies dishonourable, seeing that the Scythians, as they are most ancient, so they have been the Conquerours of most Nations, themselves alwaies invincible, and never subject to the Empire of others.”[131]

Irish legend maintains that the Scottish originate from Fenius Farsaidh, a descendant of Edom (Esau), who founded the kingdom of Scythia in southern Russia. Fenius’ son Nel married Scota the daughter of an Egyptian Pharaoh and contemporary of Moses. A Swiss genetics company has in fact claimed that up to 70 percent of British men are related to the Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamun. Y-DNA testing on some of the related male mummies of the eighteenth dynasty of Egypt revealed them to belong to a genetic profile group, known as haplogroup R1b1a2. It is the most frequently occurring Y-chromosome haplogroup in Western Europe, with its highest concentrations in Ireland and Scotland, indicating that they share a common ancestor.[132] R1b1a2 arose about 9.500 years ago in the surrounding area of the Black Sea, an area corresponding to Scythia. This should not be taken as corroborating the Scota legend, but as perhaps pointing to some underlying truth that has later been embellished by legend.