19. Renaissance & Reformation

Prisca Theologia

The modern era of European history effectively begins with the Italian Renaissance, of the fourteenth century. Conventional versions of history, designed to reinforce a secular outlook, present the Renaissance as the advent of “Humanism,” representing a liberal challenge to religious orthodoxy, which manifested itself in a flourish of bold new art, architecture, politics, science and literature. In reality, many of the famous works of the Renaissance resulted from a discovery of the works of the Corpus Hermeticum, believed to represent the survival of the Prisca Theologia, or “Ancient Wisdom,” associated with the influence of the Kabbalah, spread by Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition and the Expulsion from Spain in 1492. While many Jews of course conceded to forced conversion to avoid persecution, others seem to have used to the opportunity to carry out subversive activities against the Christian Church, often marked by the assimilation of Kabbalistic ideas into Christianity and the creation of Christian sects.

Samuel Usque (c.1500 - after 1555), a Portuguese Marrano who settled in Ferrara, wrote an apology titled the Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel, where he warned European rulers: “You should consider how much harm you bring upon yourself by compelling Jews to accept your faith, for these ways… in the end become the means that undermine and destroy them [European rulers]” Jews were God’s chosen people, Usque reminded his readers, and when they were forced to convert, they became God’s chosen agents against their oppressors: “Since throughout Christendom Christians have forced Jews to change their religion, it seems to be divine retribution that these Jews should strike back with the weapons that are put into their hands to punish those who compelled them to change their faith…”[1]

The family of the famous Kabbalist Don Isaac Abarbanel (1437 – 1508) was also associated closely with the Medicis, the famous banking family that ruled Florence and who were the chief sponsors of the Renaissance. Abarbanel was a Portuguese Jewish philosopher and financier, who was born in Lisbon, Portugal, into one of the oldest and most distinguished Iberian Jewish families, who trace their origin from King David. He referred to himself repeatedly as “Isaac of the root of Jesse, the Bethlehemite, of the holy seed, of the family of the House of David.” A student of the rabbi of Lisbon, Joseph Chaim, he became well versed in rabbinic literature and in the learning of his time, devoting his early years to the study of Jewish Kabbalah. Abarbanel had inherited his wealth from his father, the Portuguese treasurer, Dom Judah, and attracted the attention of King Afonso V of Portugal, a knight of the Order of the Garter, who employed him as treasurer. After the death of Afonso he was obliged to relinquish his office, having been accused by King John II of connivance with Fernando II of Braganza (1430 –1483).

Abarbanel became known to the royal court of Spain where he was appointed financial advisor to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. Several times, Abarbanel spent large portions of his personal wealth to bribe the Spanish Monarchy to permit the Jews to remain in Spain. In the end, he only managed to have the date for the expulsion to be extended by two days. On August 2, 1492, on Tisha B’Av, Abarbanel, carrying a Torah scroll led 300,000 fellow Jews out of Spain. Tisha B’Av (“the ninth of Av”) is regarded as the saddest day in the Jewish calendar, which traditionally commemorates the great tragedies of Jewish history, primarily the destruction of both Solomon’s Temple by the Babylonians and the Second Temple by the Romans in Jerusalem.

The Jews of Florence were one of the oldest continuous Jewish communities in Europe, and one of the largest and one of the most influential Jewish communities in Italy. The fate of Tuscan Jewry in the early modern period was inextricably linked to the favor and the fortune of the Medicis. Many Jews who settled in Florence were merchants and money lenders. The Jewish presence in Italy dates to the pre-Christian Roman period. Though a Jewish presence was registered in Lucca as early as the ninth century and a network of Jewish banks had spread throughout the region by the mid-fifteenth, the organized Jewish communities of Florence, Siena, Pisa and Livorno were political creations of the Medici rulers.

Growing persecution in other parts of Europe had led many Kabbalists to find their way to Italy, which during the Renaissance became one of the most intense areas of Kabbalistic study, second only to Palestine. According to Gershom Scholem, “the activities of these migrants strengthened the Kabbalah, which acquired many adherents in Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.” Laying the basis for the rediscovery of the occult tradition of classical philosophy was, as noted by Moshe Idel, one of the foremost scholars of the subject, has pointed out, that “Kabbalah was conceived by both Jewish and Christian Renaissance figures as an ancient theology, similar to and, according to the Jews, the source of such later philosophical developments as Platonism, Aristotelianism, Pythagoreanism, and atomism.”[2]

Kabbalist Don Isaac Abarbanel pleads before the Queen Isabella of Spain for the recission of the Edict of Expulsion but the Grand Inquisitor Thomas de Torquemada (also of Jewish descent), crucifix in hand, convinces her.

Gemistus Pletho (c. 1355/1360 – 1452/1454)

The Renaissance began during the de facto rule of Florence by Cosimo de Medici (1389 – 1464) Italian banker and politician and the first member of the Medici family. Cosimo was influenced by Gemistus Pletho (c. 1355/1360 – 1452/1454), considered one of the most important influences on the Italian Renaissance as the chief pioneer of the revival of Greek scholarship in Western Europe. As revealed in the Nomoi or Book of Laws, which he only circulated among close friends, Pletho rejected Christianity in favor of a return to the worship of the pagan gods of Ancient Greece, mixed with wisdom based on Zoroaster and the Magi.[3] Pletho drew up plans in his Nomoi to radically change the structure and philosophy of the Byzantine Empire in line with his interpretation of Platonism, and supported the reconciliation of the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches in order to secure Western Europe’s support against the Ottomans. Pletho re-introduced Plato’s ideas to Western Europe during the 1438–1439 Council of Florence, a failed attempt to reconcile the East–West schism. There, Pletho met Cosimo de Medici and influenced him to found a new Platonic Academy.

Cosimo de' Medici (1389 – 1464) was an Italian banker and politician who established the Medici dynasty as rulers of Florence during much of the Italian Renaissance.

In 1439, Cosimo began sending his agents all over the world in quest of ancient manuscripts, and in 1444 founded Europe’s first public library, the Library of San Marco, and through his commission the corpus of Platonic, Neoplatonic, Pythagorean, Gnostic and Hermetic thought was translated and became readily accessible. About 1460, a manuscript that contained a copy of the Corpus Hermeticum was brought by a monk to Florence from Macedonia. So prized was this find that, though the manuscripts of Plato were awaiting translation, Cosimo ordered that they be put aside and to proceed with their translation instead. These texts were translated by Italian philosopher Marisilio Ficino (1433 – 1499), was an Italian scholar, astrologer and Catholic priest who become one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance.

Under Ficino, the Platonic Academy would proceed to translate into Latin all of Plato’s works, the Enneads of Plotinus, and various other Neoplatonist works. However, about 1460, a manuscript that contained a copy of the Corpus Hermeticum was brought by a monk to Florence from Macedonia. So prized was this find that, though the manuscripts of Plato were awaiting translation, Cosimo ordered that they be put aside and to proceed instead with their translation. The principle figure in this tradition was Hermes Trismegistus, erroneously thought to have lived before Plato, and at times identified with Moses. Ficino was succeeded in the leadership of his academy by Pico della Mrandola (1463 – 1494), one of the first exponents of Christian Kabbalah. Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man, which is taken as a characteristic example of Renaissance humanism, begins by quoting Hermes Trismegistus, “what a great miracle is man.”

Scene of Marisilio Ficino (1433 – 1499), of the Platonic Academy, with entourage celebrating Neoplatonic wisdom around a bust of Plato.

The confluence of Kabbalistic and Hermetic influences was exemplified in the importance of the Picatrix, written by the Sabians, which was to play a formative role in the rebirth of Jewish Hermeticism in the fifteenth century.[4] Fabrizio Lelli, in “Hermes Among the Jews: Hermetica as Hebraica from Antiquity to the Renaissance,” traces a basic thread of the emergence of Hebrew Hermetica in antiquity and the early Middle Ages, their reception in the high Middle Ages by Abraham Ibn Ezra, the opposition of Maimonides, and its final reception by learned Jews of the Italian Renaissance. According to Lelli, as the humanists studied and reappraised the Hermetic works, Jewish authors, especially in Italy, would tend to resort to their own Hermetic tradition. This was especially the case with Ibn Ezra’s authoritative Commentary on the Pentateuch, which encouraged them to reconcile his views with Maimonides’ rational opposition, and to conclude that the two had actually taken the same position on the relationship between religion with science.[5]

Prominent among medieval Arabic works influenced by Hermetic notions is a series of texts attributed to King Solomon and widely read by Jews as early as the twelfth century.[6] The most renowned of them contains numerous sayings attributed to Hermes. Known in Hebrew as the Sefer Mafteah Shlomoh or “Book of Solomon’s Key,” this pseudepigraphical work achieved great fame in the fifteenth century and after as the Clavicula Salomonis. According to its introduction, Solomon wrote the book for his son Rehoboam, and commanded him to hide the book in his sepulcher upon his death. Years later, the book was discovered by a group of Babylonian philosophers repairing Solomon's tomb. The text is divided into two books. Book I contains conjurations, invocations and curses to summon and command spirits. It also describes how to find stolen items, become invisible, gain favor and love, and so on. Book II describes various purifications which the “exorcist” should undertake, how they should clothe themselves, how the magical tools are to be constructed, and what animal sacrifices should be made to the spirits. Another celebrated pseudonym was ‘‘Balinas’’ or ‘‘Belenus,’’ a garbling of ‘‘Apollonius” of Tyana. The Latin tradition connects Apollonius closely with Hermeticism, and two of his works are known in Hebrew translations from Arabic made in the thirteenth or fourteenth century.

Among other Arabic works translated into Hebrew, the Sefer ha-‘Azamim (“Book of Essences”), falsely attributed to Abraham Ibn Ezra, circulated widely in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.[7] It summarizes ‘‘the thinking of the sages of the Sabians and Nabateans’’ and describes the reception of celestial influences. Another important Jewish Hermetic treatise, Sefer Hermes, which survives in a Paris manuscript mostly taken up with astronomical works by Ibn Ezra. The Sefer Hermes, is a translation from Arabic of a significant astrological work, the Kitab fi’l Kawakib al-Babaniya (“Book on Beibenian Stars”), known in Latin as Liber de stellis beibeniis. It is the most complete Hermetic work on astrology that survives in Hebrew, and it clearly identifies Hermes with the patriarch Enoch. The short tract in Hebrew ‘‘describes the qualities of persons born under certain fixed stars associated with the temperaments of the planets at the moment when those stars occupy important positions in the sky, especially the ascendant… or the… tenth-house (or mid-heaven).’’[8]

The key representative of the Italian Kabbalists of the Renaissance was Leone Ebreo (c. 1465 – c. 1523), the son of Don Isaac Abarbanel. Abarbanel used medieval Judeo-Arabic material that included some of the same magical and Hermetic teaching that interested the humanists. In his Yeshu‘ot Mes hiho (“Redemptions of His Messiah”), Abarbanel evidenced his familiarity with Ficino’s Latin version of the Corpus Hermeticum, and his Mif‘alot Elohim (“Deeds of God”) cites a number of Hermetic sayings. He identifies Hermes with Enoch, while also speaking of Pythagoras and Plato, an idea also found in the work of Isaac’s son, Judah (c. 1460 – 1530).

Following medieval Jewish sources, Ebreo saw Plato as dependent on the revelation of Moses, and even as a disciple of the ancient Kabbalists. While Rabbi Yehudah Messer Leon, a committed Aristotelian, criticized the Kabbalah’s similarity to Platonism, his son described Plato as a divine master. Other Kabbalists, such as Isaac Abarbanel and Rabbi Yohanan Alemanno believed Plato to have been a disciple of Jeremiah in Egypt.[9]

In Ge Hizzayon or Valley of Vision, by Rabbi Abraham Yagel (c. 1553 – 1624), Hermes and Abraham ibn Ezra are mentioned together in a discussion of scientific issues.[10] On the similarity of the teachings of the Greek philosophers and the Kabbalah, Yagel commented:

This is obvious to anyone who has read what is written on the philosophy and principles of Democritus, and especially on Plato, the master of Aristotle, whose views are almost those of the Sages of Israel, and who on some issues almost seems to speak from the very mouth of the Kabbalists and in their language, without any blemish on his lips. And why shall we not hold these views, since they are ours, inherited from our ancestors by the Greeks, and down to this day great sages hold the views of Plato and great groups of students follow him, as is well known to anyone who has served the sage of the Academy and entered their studies, which are found in every land.[11]

Ficino wished to revive the ancient pagan mystery teachings of the “Chaldeans, Egyptians and Platonists.” Ficino’s mission was to revive the ancient pagan mystery teachings of the “Chaldeans, Egyptians and Platonists,” characterized as representing the Prisca Theologia, or Ancient Wisdom, considered a pure tradition imparted to the wise men of antiquity, and the key to establishing a universal religion that could reconcile Christian belief with ancient philosophy. Ficino presented a family tree of wisdom starting chronologically with Zoroaster, then Hermes Trismegistus, Orpheus, Aglaophemus, Pythagoras and Plato. According to Ficino, in the preface to the Plotinus commentaries, the divine theology began simultaneously with Zoroaster among the Persians and Hermes among the Egyptians, and that this wisdom tradition led in an unbroken chain to Plato, by way of Orpheus and Pythagoras. Ficino also completed translations of the Sayings of Zoroaster and the Hymns of Orpheus.

Pletho may also have been the source for Ficino’s Orphic system of natural magic.[12] Ficino advocated the regular singing of Orphic hymns, which he believed echoed the music of the spheres. He believed an individual would submit to a symbolic death and rebirth, and emerge with what was perceived as a new identity, often denoted by a new name. If such a ritual were conducted under the proper astrological conditions, one could even, theoretically, correct deficiencies in one’s horoscope.

Astrological Magic

Birthday and parentalia of Plato (428 BC-348 or 427 or 347 BC), celebrated by Lorenzo “the Magnificent” de' Medici (1449 – 1492) at Villa di Careggi, site of the Platonic Academy

Lorenzo “the Magnificent” de' Medici (1449 – 1492)

The grandson of Cosimo de Medici, Lorenzo de Medici (1449 – 1492), also known as “the Magnificent” (Lorenzo il Magnifico) by contemporary Florentines, was responsible for an enormous amount of arts patronage, encouraging the commission of works from Florence’s leading artists. Including Leonardo da Vinci, Botticelli, and Michelangelo, their works often featured pagan themes that challenged the tolerance of the Church. Of the twenty-seven figures portrayed in Raphael’s School of Athens is Zoroaster, holding a celestial sphere. Through the influence of Neoplatonism and Hermeticism, the recovery of ancient learning during the Renaissance was concerned mainly with astrology.

Renaissance humanism did not help to diffuse interest in the “irrational.” “On the contrary,” noted Jean Seznec, in The Survival of the Pagan Gods: The Mythological Tradition and its Place in Renaissance Humanism and Art, “the first effect of humanism was to encourage astrology.”[13] Seznec has demonstrated that the artists of the Middle Ages relied primarily on literary sources, and often from mythographers of late antiquity. In their desire to depict the mythological themes of antiquity, they did not have access to classical models on which to base their work, and therefore, without any sort of visual model, rarely provided accurate details as to how the gods of Greek mythology ought to be portrayed. Seznec has indicated that, beginning in the twelfth century, European artists began to turn away from traditional sources, in favor of Arab works, which were more astronomically accurate.

Often, Renaissance artists looked to the Picatrix, which focused particularly on what it called “talismans”, which it compared explicitly to the alchemical elixir. Through the proper design and construction of a talisman, and through proper performance of the rituals associated with it, the magician could control the energy emanating from heavenly spheres. In the form of angelic entities or spirits, he could, for instance, command the powers of Mars in matters of war, of Venus in matters of love. Thus, the Hermetic magician learned “to draw these celestial spirits down to earth and to induce them to enter into a material object, the talisman.”[14]

Astrological talismans from the Picatrix of the Sabians

The Picatrix describes some fifty images of stars, planets, and zodiac signs, which, if engraved, preferably on precious stones, according to the aspects of the heavens at some favorable moment, were supposed to receive the greatest possible amount of celestial influence to store it away for future use. For the favor of Jupiter, for instance, a white stone should be engraved with the figure of a crowned figure seated on a throne, his hand upraised, each of the four feet of the throne must rest on the neck of a winged man, the same manner in which Pausanias had described Olympian Zeus. For the favor of Mars, one requires a gem engraved with the image of “a young man, naked, at his right a young girl with hair knotted at the back of her head; his left hand rests on her breast, his right on her neck, and he gazes into her eyes.”[15]

Arab figures showed almost no relation to Greco-Roman planetary types. Having acquired their knowledge of astronomy from the Sabians, their descriptions resemble types found in Babylonian sources. Therefore, to the Arabs, Mercury, as a pious and scholarly figure, corresponded to the Babylonian Nebo, the writer-god. Jupiter, as judge to Marduk, who signs the decrees of destiny. The Sun himself, who wears a crown and holds a sword on his knees, is close to Shamash. In Florence, the planetary gods sculptured on the Campanile of Giotto appear in such guises. The Sun is a descendant of oriental gods, presented as a king holding a scepter in his left hand and in his right a sort of wheel. Similarly, in the Capella degli Spagnuoli, Saturn holds a spade in addition to the classical sickle, Mercury appears as a scribe, indicating that the figure represented the scholarly Nebo. For the same reason, the choir of the Eremitani at Padua, and on a capital in the Doge’s Palace in Venice, Mercury has assumed the likeness of a teacher.

Renaissance artists did much to liberate these images from their Oriental models, and represented them as if they were contemporary figures. At times, the foreign gods are portrayed in Christian garb. Marduk or Jupiter of the Campanile in Florence is presented in a monk’s robe, holding a chalice in one hand, and in the other a cross. Jupiter is the ruler of the Western countries, therefore, as the Picatrix explains, when praying to him, “be humble and modest, dressed in the manner of monks and Christians, for he is their patron; act in every way as the Christians do, and wear their costume: a yellow mantle, a girdle, and a cross.”[16]

Ficino wrote extensively about the techniques through the use of amulets, talismans, unguents and elixirs, whereby planetary powers might be invoked by the principles of Hermetic analogy. Based on his knowledge of the works of Hermetic texts, Ficino, in Libri de Vita, first published in 1489, advocated a kind of astral magic involving the use of talismans. Particularly influential for Ficino among Neoplatonists would have been Iamblichus’ On the Egyptian Mysteries, devoted to a subject treated in the Ascflepius, the “Egyptian” art of drawing spirits into statues. There were plenty of mediaeval and Arab authorities he might have used who give lists of talismanic images, and the possibility that he may have used the Picatrix is substantiated by the similarity of some of the images, which he describes, with those in the Picatrix. Through such techniques, Ficino declared, “one could avoid the malignity of fate.”[17]

Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus.

Melancholia by Albrecht Dürer (1514)

It was not until the excavation of thousands of coins, reliefs, and statues in the sixteenth century, that European artists rediscovered classical representations of mythological figures, allowing them to recreate their traditional forms, and thus transform the Western artistic tradition. Nevertheless, under the influence of Ficino, these tended to be works of astral magic, of the manner described in the Picatrix. Thus, according to Frances Yates:

The phenomenon is exactly parallel with that other phenomenon which Warburg and Saxl discovered and studied, namely how the images of the gods were preserved through the Middle Ages in astrological manuscripts, reached the Renaissance in that barbarised form, and were then reinvested with classical form through the rediscovery and imitation of classical works of art… One might say that the approach through the history of magic is perhaps as necessary for the understanding of the meaning and use of a Renaissance work of art as is the approach through the history of the recovery of classical form for the understanding of its form.[18]

Botticelli, for one of the most recognized artworks of the Renaissance, the Primavera, had consulted Ficino. Frances Yates commented: “I want only to suggest that in the context of the study of Ficino’s magic the picture begins to be seen as a practical application of that magic, as a complex talisman, an image of the world arranged so as to transmit only healthful, rejuvenating, anti-Saturnian influences to the beholder.”[19] Botticelli’s three works, being some of the most recognized Renaissance paintings, the Minerva and the Centaur, The Birth of Venus, and the Primavera, commissioned for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de Medici, all dealt with occult themes and represent the magical practice of drawing down planetary influences into images. Studies have shown that German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer took his inspiration from Ficino. The figure in the Melancholia of Dürer, symbolizes the “children of Saturn,” who in obedience to her, meditate on the secrets of wisdom.

Black Nobility

John Collier A glass of wine with Caesar Borgia, from left: Cesare Borgia, Lucrezia, Pope Alexander VI, and a young man holding an empty glass.

The Medicis were one of several influential Italian families, sometimes referred to as the Black Nobility, who included the Orsini, Farnese and Borgia families, often protectors of the Jews, at times even suspected of being secretly Jews, who also produced a number of popes. According to their family legend, the Orsini, one of the most influential princely families in medieval Italy and Renaissance Rome, are descended from the Julio-Claudian dynasty of ancient Rome. Members of the Orsini family include three popes: Celestine III (1191 – 1 198), Nicholas III (1277 – 1 280), and Benedict XIII (1724 – 1 730). In addition, the family membership includes 34 cardinals, numerous condottieri, and other significant political and religious figures. The titles of Duke of Parma and Piacenza and Duke of Castro were held by various members of the Farnese family. Its most important members included Pope Paul III (1468 – 1549), Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (1520 – 1589), Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma (a military commander and Governor of the Spanish Netherlands), and Elisabeth Farnese, who became Queen of Spain and whose legacy was brought to her Bourbon descendants.

Investiture of Johann Siebenhirter as the first Grand Master of the Austrian Order of Saint George by Frederick III (1415 –1493), Holy Roman Emperor, blessed by Pope Paul II.

The House of Borgia, an Italo-Spanish noble family from Aragon, which rose to prominence during the Italian Renaissance, was widely rumored to be of Jewish origin.[20] Such rumors were propagated by, among others, Pope Julius II. Because the family came from Valencia, the Borgias were often called Marranos. The Borgias became prominent in ecclesiastical and political affairs in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, producing two popes: Pope Callixtus III during 1455 – 1458, and Pope Alexander VI, during 1492 – 1503. Pope Alexander VI, born Rodrigo de Borja, joined the Society of Saint George, founded in 1503 by Emperor Maximilian I, who became Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Fleece after he married Mary of Burgundy, the granddaughter of the order’s founder, Philip the Good.[21] The society was a revival of the Austrian Order of Saint George founded by his father Frederick III, son of Ernst the Iron, a member of the Order of the Dragon, to perpetuate the original order founded by his ancestor, Rudolf I of Germany, whose daughter Clemence of Austria was the mother of Charles I of Hungary, founder of the Order of Saint George of Hungary.[22] Charles I’s granddaughter Mary was the first wife of Emperor Sigismund, who founded the Order of the Dragon, inspired by his order.

Especially during the reign of Alexander VI, the Borgia were suspected of many crimes, including adultery, incest, simony, theft, bribery, and murder, especially by arsenic poisoning.[23] According to the papal master of ceremonies, Johann Burchard:

There is no longer any crime or shameful act that does not take place in public in Rome and in the home of the Pontiff. Who could fail to be horrified by the… terrible, monstrous acts of lechery that are committed openly in his home, with no respect for God or man? Rapes and acts of incest are countless…[and] great throngs of courtesans frequent St. Peter’s Palace, pimps, brothels, and whorehouses are to be found everywhere![24]

Among Alexander VI’s more notorious children from his mistress Vannozza dei Cattanei were Cesare (1433 – 1499) and the notorious femme fatale Lucrezia Borgia (1480 – 1519). It was rumoured that Lucrezia carried on an incestuous relationship with her father and possessed a hollow ring that she used frequently to poison drinks. Cesare Borgia was a major inspiration for The Prince by Machiavelli. Cesare apparently walked through the streets of Rome with weapons partly concealed under his robes, taking pot-shots at prisoners and murdering close relations. He was rumored to have committed incest with Lucrezia, and stabbed her lover to death at the feet of the Pope, and strangled her second husband, Alfonso of Aragon, an illegitimate son of the King of Naples, who was only 18-years-old.[25]

Several rumors have persisted throughout the years, primarily speculating as to the nature of the extravagant parties thrown by the Borgia family. One example is the Banquet of Chestnuts, a supper purportedly held in the Papal Palace by former Cardinal Cesare Borgia. An account of the banquet is preserved in a Latin diary by Protonotary Apostolic and Master of Ceremonies Johann Burchard (c. 1450 – 1506), titled Liber Notarum:

On the evening of the last day of October, 1501, Cesare Borgia arranged a banquet in his chambers in the Vatican with “fifty honest prostitutes.” called courtesans, who danced after dinner with the attendants and others who were present, at first in their garments, then naked. After dinner the candelabra with the burning candles were taken from the tables and placed on the floor, and chestnuts were strewn around, which the naked courtesans picked up, creeping on hands and knees between the chandeliers, while the Pope, Cesare, and his sister Lucretia looked on. Finally, prizes were announced for those who could perform the act most often with the courtesans, such as tunics of silk, shoes, barrets, and other things.

In 1486, when Pico went to Rome to defend his Hermetically oriented ideas, his theses were branded as heretical. The ensuing public outcry necessitated an Apology, which was published in 1487, together with most of the Oration. Pico was finally rescued from his troubles with the death of the presiding pope and the intervention of Lorenzo de Medici. The ban was rescinded in 1493 by the hermetically interested Alexander VI.[26]

Bonfire of the Vanities

Painting (1650) of Savonarola's execution in the Piazza della Signoria.

Fra Girolamo Savonarola (1452 –1498)

Lorenzo the Magnificent died in 1492 and was succeeded by his son Piero di Lorenzo de Medici (1472 – 1503), called Piero the Unfortunate, who was overthrown by the followers of Fra Girolamo Savonarola (1452 – 1498), a Dominican monk who became known in Italy for his sermons about the End of Days. In the 1490s, under the Catholic theocracy of Savonarola, both the Medici and the Jews were expelled from Florentine territory. Savonarola was a Dominican friar who was assigned to work in Florence in 1490, largely thanks to the request of Lorenzo de’ Medici—an irony, considering that within a few years Savonarola became one of the foremost enemies of the Medici house and helped to bring about their downfall in 1494.[27] In 1482, Savonarola was assigned as lector in the Convent of San Marco in Florence. In 1487, he left San Marco for a new assignment, and tor the next several years Savonarola lived as an itinerant preacher. In 1490, Savonarola was reassigned to San Marco due to the initiative of Pico della Mirandola, who had been impressed with his learning and piety. Pico, who was in trouble with the Church for some of his unorthodox, was living under the protection of Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Medici de facto ruler of Florence. To have Savonarola beside him as a spiritual counsellor, Pico persuaded Lorenzo that the friar would bring prestige to of San Marco and its patrons the Medici.[28]

Savonarola began to draw large crowds for his preaching on the First Epistle of John and on the Book of Revelation, calling for repentance and renewal before the arrival of a divine scourge. in 1494, Charles VIII of France (1470 – 1498), decided to cross the Alps with an army in order to assert hereditary claims to the Kingdom of Naples, to secure his rights to the Neapolitan throne that René of Anjou had left to his father, Louis XI. Upon the conquest of Naples, Savonarola declared Charles VIII the expected avenger:

I have said and many times reconfirmed that the King of France was chosen by God as minister of his justice and that he will be victorious and prosper even if all the world be against him. It is true that, as I have particularly said and written to him, to pre- serve him in humility and on account of the bad things his subjects do if he does not correct them, he will have many tribulations, and the greatest of all if he does not treat well the city of Florence, chosen by God for the beginning of the reformation of Italy and the Church: and if he does not choose to be the friend of the Florentine people through love, God will make him so through force.[29]

After the French forces banished the Medici and left Savonarola the de facto ruler of Florence, the Florentines embraced his campaign to rid the city of “vice.” Savonarola campaigned against what he considered to be the artistic and social excesses of Renaissance Italy, preaching with great vigor against any sort of luxury. His power and influence grew so that with time he became the effective ruler of Florence. In 1495, when Florence refused to join Pope Alexander VI’s Holy League against the French, the Vatican summoned Savonarola to Rome. He disobeyed and further defied the pope by preaching under a ban, highlighting his campaign for reform with public demonstrations of piety and a “bonfires of the vanities.” A bonfire of the vanities is a burning of objects condemned by authorities as occasions of sin on the day of Carnival. The phrase usually refers to the bonfire of February 7, 1497, when Savonarola’s supporters collected and publicly burned thousands of objects such as cosmetics, art, and books in Florence, Italy, on the Shrove Tuesday festival. Shrove Tuesday is the day in February or March immediately preceding Ash Wednesday, which is celebrated in some countries where it is called Mardi Gras.

Savonarola collected various objects that he considered to be objectionable, such as manuscripts, ancient sculptures, antique and modern paintings, priceless tapestries, and many other valuable works of art, as well as mirrors, musical instruments, and books of divination, astrology, and magic. He destroyed the works of Ovid, Propertius, Dante, and Boccaccio. So great was his influence that he even managed to obtain the cooperation of major contemporary artists such as Sandro Botticelli and Lorenzo di Credi, who reluctantly submitted some of their own works for destruction.[30]

However, Savonarola gained the disdain of Pope Alexander VI, and was eventually excommunicated on in 1497.[31] Having been charged by Alexander VI with heresy and sedition, he was executed on 1498, hung on a cross and burned to death, in the Piazza della Signoria, where he had previously held his. The papal authorities ordered that anyone in possession of the Friar’s writings had four days to turn them over to a papal agent to be destroyed. Anyone who failed to do so faced excommunication.[32]

Sistine Chapel

A member of the Medici family was not to rule Florence again until 1512, when the city was forced to surrender by Giovanni de Medici (1475 – 1521), the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who in 1513 was elected Pope Leo X, solidifying the family’s power. Leo X’s mother was Clarice Orsini, a descendant of King John of England, the youngest of the four surviving sons of King Henry II of England and Duchess Eleanor of Aquitaine. Leo X, who had been educated by Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, exhibited a profligacy that was characteristically un-Christian. Two contemporary historians, Francesco Guicciardini and Paolo Giovio, seemed to share the belief that Leo engaged in “unnatural vice” while pope.[33] Zimmerman notes Giovio’s “disapproval of the pope’s familiar banter with his chamberlains – handsome young men from noble families – and the advantage he was said to take of them.”[34] As he was described by Joseph McCabe in Crises in the History of the Papacy:

Leo gathered about him a company of gross men: flatterers, purveyors of indecent jokes and stories, and writers of obscene comedies which were often performed in the Vatican with cardinals as actors. His chief friend was Cardinal Bimmiena, whose comedies were more obscene than any of ancient Athens or Rome and who was one of the most immoral men of his time. Leo had to eat temperately for he was morbidly fat, but his banquets were as costly as they were vulgar and the coarsest jesters and loosest courtesans sat with him and the cardinals. Since these things are not disputed, the Church does not deny the evidence of his vices. In public affairs he was the most notoriously dishonourable Vicar of Christ of the Renaissance period, but it is not possible here to tell the extraordinary story of his alliances, wars and cynical treacheries. His nepotism was as corrupt as that of any pope, and when some of the cardinals conspired to kill him he had the flesh of their servants ripped off with red-hot pincers to extract information.[35]

Raphael's Portrait of Pope Leo X (1475 – 1521), born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, with cardinals Giulio de' Medici (later Pope Clement VII) and Luigi de' Rossi, his first cousins

Leo X’s death in 1521 briefly interrupted Medici power until his cousin Cardinal Giulio de Medici (1478 – 1534) was elected Pope Clement VII in 1523. Clement VII had served as chief advisor to Leo X and his successor Pope Adrian VI. Clement VIII left a significant cultural legacy in the Medici tradition. He commissioned works of art by Raphael, Benvenuto Cellini, and Michelangelo, including the The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel. Clement is best known for approving, in 1533, Copernicus’ theory that the Earth revolves around the Sun, nearly a century before Galileo was tried for heresy for similar ideas. Clement is remembered for orders protecting Jews from the Inquisition, approving the Theatine and Capuchin Orders, and securing the island of Malta for the Knights of Malta.

Pope Paul III (1468 – 1549), born Alessandro Farnese.

Michelangelo too may have been influenced by Hermeticism and Ficino’s ideas, having been exposed to them through his presence at the court of the Medicis. He contributed to the planning of the Medici Chapel, which was added to the Church of San Lorenzo in Florence, the site of the Tomb of Cosimo, patriarch of the Medicis. Likewise, Michelangelo too was influenced by the anthropomorphism of the Kabbalah, painting “God” creating Adam in the Sistine Chapel, which is actually a depiction of the “Ancient of Days.” He is described in the Book of Daniel as, “I beheld till the thrones were cast down, and the Ancient of Days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire.” In the Kabbalah, there is mention of the Ancient of Ancients and the Holy Ancient One interpreted as synonymous with the En Sof, the unmanifested Godhead. There are several references to this particular name of God in the Zohar, which goes into great detail describing the White Head of God and ultimately the emanation of its personality or attributes.[36]

Clement VIII was succeeded by Pope Paul III, who was born Alessandro Farnese. A friend of Alexander VI, Paul III was consecrated by Leo X and ruled as pope from 1513 to 1521. Paul III was attacked by some for supporting and protecting Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, for its nudity and pagan themes. The pope’s Master of Ceremonies Biagio da Cesena is reported to have said: “it was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.”[37] Michelangelo then painted Cesena’s face into the scene as Minos, a figure from Greek mythology judging of the underworld, and with donkey ears, while his nudity is covered by a coiled snake. When Cesena complained to Paul III, the pope joked that his jurisdiction did not extend to Hell, so the portrait would have to remain.[38]

Protestant Reformation

Luther at the Diet of Worms in 1521

Savonarola’s push for reform found a reception in Germany and Switzerland, among the early Protestant reformers, most notably Martin Luther. Clement VII inherited unprecedented challenges, including Luther’s Protestant Reformation in Northern Europe. The propensity for extravagant expenditure by Leo X finally depleted the Vatican’s finances and he turned to selling indulgences to raise funds. An indulgence is the full or partial remission of temporal punishment due for sins which have already been forgiven, and which Leo X exchanged for those who donated alms to rebuild St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. It was mainly due to these excesses, which he saw as the sale of salvation, that led Martin Luther to post his Ninety-Nine Theses in 1517, which set off the Protestant Reformation. Luther’s refusal to renounce any of his writings at the demand of Leo X in 1520 and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521, resulted in his excommunication and condemnation as an outlaw. At the end of the Diet of Worms, Charles V issued the Edict of Worms, which condemned Luther as “a notorious heretic” and banned citizens of the Empire from preaching his ideas. In fear for his life, Luther escaped to Wartburg castle, site of Elizabeth of Hungary’s Miracle of the Roses, and the Grail castle Munsalvaesche, visited by the Knight Swan Lohengrin. There, Luther devoted his time to translating the New Testament from Greek into German and other polemical writings.

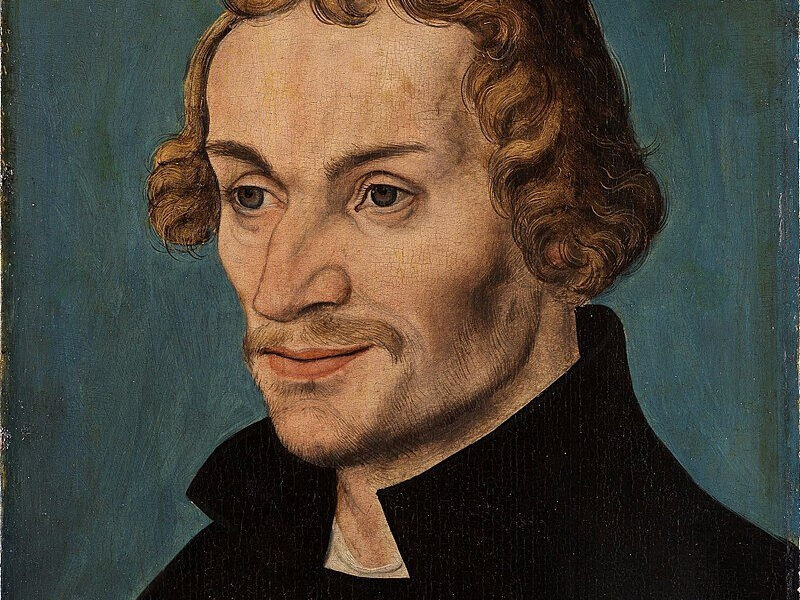

Philip Melanchthon (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 1497 – 1560).

Luther gained the trust of his followers by exposing the fraudulent promises of salvation called “indulgences” sold by Leo X, to open them up to his own dubious theology. The teachings of Jan Hus—the heretic who was supported by Emperor Sigismund, founder of the Order of the Dragon, but was burned at the stake following the Council of Constance in 1415—had a strong influence on Luther.[39] When Luther was passing through Naumburg to attend the Diet of Worms, a priest forced his way through the crowds and presented him a portrait to Savonarola, accompanied by a letter calling on Luther to stand on the Lord’s side. Luther took the portrait, gave it a long steady gaze, the kissed it and announced: “That man was, indeed, a faithful servant of Jesus Christ.”[40] Meister Eckhart’s Theologia Germanica was also a favorite of Luther, and which was viewed by some historians of the early twentieth century as pivotal in provoking Luther’s actions and the resulting Protestant Reformation. Luther also read some of Savonarola’s writings and praised him as a martyr and forerunner whose ideas on faith and grace anticipated his own teaching of justification by faith alone, one of his most controversial doctrines.

Luther, related Louis I. Newman, was interested for a time in the Kabbalah, perhaps under the influence of the works of Johann Reuchlin (1455 – 1522), whose nephew was Philipp Melanchthon (1497 – 1560), Luther’s chief collaborator. During his second visit to Rome in 1490, Reuchlin became acquainted with Pico della Mirandola at Florence, and, learning from him about the Kabbalah, he became interested in Hebrew.[41] Following Pico, Reuchlin seemed to find in the Kabbalah a profound theosophy which might be of the greatest service for the defense of Christianity and the reconciliation of science with the mysteries of faith, a common notion at that time. Reuchlin’s Kabbalistic ideas were expounded in the De Verbo Mirifico, and finally in the De Arte Cabbalistica, in which he shared with Pope Leo X how he had met with Pico and his circle of philosophers who were reviving the ancient wisdom.

Luther himself supported Reuchlin in a controversy known as “The Battle of the Books,” which became a debate that involved the leading thinkers and rulers of Europe. Heinrich Graetz and Francis Yates contended that this affair helped spark the Protestant Reformation.[42] Many of Reuchlin’s contemporaries thought that the first step to the conversion of the Jews was to take away their books. This view was advocated by Johannes Pfefferkorn, a Jewish convert to Catholicism and a follower of the Dominicans, who preached against the Jews and attempted to destroy copies of the Talmud, and engaged in a pamphleteering battle with Reuchlin. The Pfefferkorn controversy caused a wide rift in the church and eventually the case came before the papal court in Rome. When, in 1517, Reuchlin received the theses propounded by Luther, he exclaimed, “Thanks be to God, at last they have found a man who will give them so much to do that they will be compelled to let my old age end in peace.”[43] “It was thus a Jewish issue,” explains Louis I. Newman, “which helped ignite the fires of the Reformation; a conflict over a Jewish question created the milieu in which Luther’s movement emerged and developed, just as the Judaizing heresies of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were in part stimulated by the debate over the Talmud.”[44]

Johann Reuchlin (1455 – 1522)

Melanchthon was like a son to Reuchlin until the Reformation estranged them. Melanchthon was the primary founder of Lutheranism after Luther, and the author of the Augsburg Confession, the primary doctrinal statement of the Protestant movement. Melanchthon was also the author the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, in which he wrote, “I would rather die than be separated from Luther,” whom he afterward compared to Elijah, and called “the man full of the Holy Ghost.” Melanchthon exclaimed at Luther’s death, “Dead is the horseman and chariot of Israel who ruled the church in this last age of the world!”[45]

Luther’s comment that justification by faith was the “true Cabala” in his Commentary on Galatians has been explained as relating to the influence of Reuchlin.[46] Although his stance on the subject was often contradictory, in Refutation of the Argument of Latomus, he argued that every good work designed to attract God’s favor was a sin. All humans are sinners by nature, he explained, and God’s grace alone can make them just. Luther advised Melanchthon: “Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides.”[47]

Luther widened his critique from indulgences and condemned as idolatry the idea that the mass is a sacrifice and rejected compulsory confession. In The Judgement of Martin Luther on Monastic Vows, he assured monks and nuns that they could break their vows without sin, because vows were an illegitimate and vain attempt to win salvation.[48] Luther, who had long condemned vows of celibacy, married Katharina von Bora, one of twelve nuns he arranged for them to be smuggled out in herring barrels from the Nimbschen Cistercian convent in 1523, setting a model for the practice allowing Protestant clergy to marry.

The role of Jewish converts in the spread of the doctrines behind the Reformation has been pointed out on several occasions. During the Middle Ages, Jewish converts who attacked their former faith included Nicholas Donin, Paul Christian, Abner-Alphonso of Burgos (c. 1270 – c. 1347), John of Valladolid (b. 1335), Paul of Burgos (c. 1351 – 1435) and Geronimo de Santa Fe (fl. 1400 – 1430). Impelled by his hatred of Talmudic Judaism, Paul of Burgos, an erudite scholar of Talmudic and rabbinical literature, composed the Dialogus Pauli et Sauli Contra Judæos, sive Scrutinium Scripturarum, which was a source for Luther’s On the Jews and their Lies. Victor von Carben, who was involved in the Pfefferkorn controversy, Emmanuel Tremellius, who published a Latin version of the Hebrew Bible, Jochanan Isaac, the author of two Hebrew grammars, and his son Stephen, all became Protestants and wrote polemics against Catholicism.

At first, Luther’s challenge to Roman Catholicism was welcomed by Jews who had been victimized by the Inquisition, and who hoped that breaking the power of the Church would lead to greater tolerance of other forms of worship. As explained by Samuel Usque, since so many Marranos left Spain for England, France and Germany, as well as the Low Countries, “that generation of converts has spread all over the whole realm, and though a long time has elapsed, these converts still give an indication of their non-Catholic origin by the new Lutheran beliefs which are presently found among them, for they are not comfortable in the religion which they received so unwillingly.”[49] There were even some, like Abraham Farissol, who regarded Luther as a Crypto-Jew, a reformer bent on upholding religious truth and justice, and whose iconoclastic reforms were directed toward a return to Judaism.[50] Some scholars, particularly of the Sephardi diaspora, such as Joseph ha-Kohen (1496 – c. 1575), were strongly pro-Reformation.[51]

According to Rabbi Abraham ben Eliezer Halevi (c. 1460 - after 1528), a Sephardic rabbi and kabbalist affiliated with Abraham Zacuto and Isaac Abarbanel, the Reformation was a crisis through which the world must pass before the arrival of the messiah, where Luther was God’s agent sent to destroy corrupt Rome before the end of the world. Halevi claimed to have referred to Luther, when foretold before the Reformation, as early as 1498, “that a man will arise who will be great, valiant, and mighty. He will pursue justice and loathe debauchery. He will Marshall vast armies, originate a religion, and destroy the house of the clergy.”[52] Halevi was aware of Luther’s treatise, written in 1523, titled That Jesus Christ was Born a Jew, where he argued that as Judaism was firmly founded in Scripture, to be a good Christian one had almost to become a Jew, and if the Catholic authorities persecute him as a heretic, they would prosecute him as a Jew.

Like many of his contemporaries, Halevi believed that the year 1524 would be the beginning of the messianic era and that the Messiah himself would appear in 1530–31. About 1524, Jews coming from Europe described with joy to Halevi in Jerusalem the anti-clerical tendencies of the Protestant reformers. On the basis of this report, the Kabbalists regarded Luther as a kind of crypto-Jew who would educate Christians away from the bad elements of their faith.[53] Halevi related that a great astrologer in Spain, named R. Joseph, wrote in a forecast on the significance of the sun’s eclipse in the year 1478, as prophesying a man who would reform religion and rebuild Jerusalem. Halevi adds that “at first glance we believed that the man foreshadowed by the stars was Messiah b. Joseph [Messiah]. But now it is evident that he is none other than the man mentioned [by all; i.e., Luther], who is exceedingly noble in all his undertakings and all these forecasts are realized in his person.”[54]

The several Jewish converts to Lutheranism, whom Luther knew, influenced him in many directions. These included Matthew Adrian, a Spanish Jew, the teacher of Conrad Pellican, the grammarian, and Fabritius Capito, a friend of Erasmus. Luther sought the advice of Jewish students and Rabbis on numerous occasions. Jews paid visits at his home to discuss with him difficult passages of the Bible, especially for the revision of his translation. On one occasion, three Jews, Shmaryah, Shlomoh and Leo visited him in Wittenberg, and expressed their joy that Christians were now busying themselves with Jewish literature and mentioned the hope among many Jews that the Christians would enter Judaism en masse as a result of the Reformation.[55]

Doctor Faustus

Johannes Trithemius (1462 – 1516), the “Devil’s abbot.”

Luther and Reuchlin were important figures of what is called the German Renaissance, part of the Northern Renaissance, a cultural and artistic movement that spread among German thinkers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which developed from the Italian Renaissance. Also active during the period was Johannes Trithemius (1462 – 1516), a German Benedictine abbot and a polymath, who was denounced as the “Devil’s abbot.” Trithemius was said, at the request of Emperor Maximillian I, to have summoned the ghosts of Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, as well as the emperor’s deceased wife Mary of Burgundy, daughter of Philip the Good, founder of the Order of the Golden Fleece.[56] Trithemius’ most famous work, Steganographia, was placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1609 and removed in 1900. The book, which is in three volumes, is about magic, specifically about using spirits to communicate over long distances.

The astrological and angelogical basis for Trithemius’ occult theory is set forth in his De septem secundeis (1508), the celestial scheme of which establishes a repetitive succession of historical cycles of seven angelic periods, a work drawing upon the Arabic work the ninth century Sabian astronomer Abu Ma’shar, Latinized as Albumasar (787 – 886), De magnis coniunctionibus et annorum revolutionibus.[57] The cycles are governed by seven “secondary intelligences,” said to rule under the supervision of the “First Intelligence,” God the Creator. Adopting the names of these ruling powers from Kabbalah, Trithemius identified them in hierarchical order as Orifiel for Saturn, Anael for Venus, Zachariel for Jupiter, Raphael for Mercury, Samael for Mars, Gabriel for the moon, and Michael for the sun. According Trithemius’ chronological scheme, follows the Platonic Great Year of 2160 years divided into six-fold periods of 354 years and 4 months, with the seven-interval cycles repeated in continuous revolutions until they are terminated apocalyptically.[58]

Despite Trithemius’ efforts to distinguish his own divinely sanctioned magic, he subsequently acquired a diabolical legend of his own resembling that of Johann Georg Faust (c. 1480 or 1466 – c. 1541), an itinerant alchemist, astrologer and magician, whose story of selling his soul to the Devil inspired Marlowe’s The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus (1604) and Goethe’s drama Faust (1808). Trithemius warned Johannes Virdung in a letter dated August 20, 1507, of a certain Georgius Sabellicus, a trickster and fraud styling himself Georgius Sabellicus, Faustus junior, fons necromanticorum, astrologus, magus secundus, etc. According to Trithemius, Sabellicus boasted of his powers, even claiming that he could easily reproduce all the miracles of Christ. Trithemius alleges that Sabellicus received a teaching position in Sickingen in 1507, which he abused by indulging in sodomy with his male students, though evading punishment by a timely escape.[59] According to Johannes Manlius, drawing on notes by Melanchthon, in his Locorum communium collectanea (1562), Johannes Faustus was a personal acquaintance of Melanchthon who described him as a “sewer of many devils.” Manlius recounts that Faust had boasted that the victories of the Emperor Charles V in Italy were due to his magical intervention.[60]

Paracelsus (1493/4 – 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim.

Trithemius was a teacher to both the alchemists Paracelsus (1493/4 – 1541) and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa (1486 – 1535). As a physician of the early sixteenth century, Paracelsus held a natural affinity with the Hermetic, Neoplatonic, and Pythagorean philosophies central to the Renaissance, a world-view exemplified by Ficino and Pico. Astrology was a very important part of Paracelsus’ medicine and he was a practicing astrologer, as were many of the university-trained physicians working at that time in Europe. Erasmus of Rotterdam witnessed Paracelsus medical skills at the University of Basel, and the two scholars initiated a letter dialogue on medical and theological subjects.[61]

Paracelsus was one of the most famous figures in the history of alchemy, known as the man who through his development and use of chemically prepared medicines, established the basis for the study of pharmacy. Paracelsus was born in 1493, given the name of Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombast von Hohenheim, but later changed his name to Paracelsus, meaning “beyond Celsus,” a reference to the first century Roman physician. After traveling throughout Europe and to the Middle East, he was appointed as Basel’s official physician. Paracelsus began to attract students from all over Europe and set off a storm of controversy that began when he made the bold announcement that his lectures would be based, not on the traditional teachings of accepted authorities, but on his own experiences and methods. He is to have said, “the universities do not teach all things, so a doctor must seek out old wives, gypsies, sorcerers, wandering tribes, old robbers, and such outlaws and take lessons from them. A doctor must be a traveler.”[62] To emphasize his break with tradition, he burned the works of Galen and Avicenna, the “Prince of Physicians,” at the bonfire held on Saint John’s Day.

The creation of a homunculus (“little person") a representation of a small human being which corresponds to the golem of the Kabbalah, first appears by name in alchemical writings attributed to Paracelsus, De natura rerum (1537):

That the sperm of a man be putrefied by itself in a sealed cucurbit for forty days with the highest degree of putrefaction in a horse's womb, or at least so long that it comes to life and moves itself, and stirs, which is easily observed. After this time, it will look somewhat like a man, but transparent, without a body. If, after this, it be fed wisely with the Arcanum of human blood, and be nourished for up to forty weeks, and be kept in the even heat of the horse's womb, a living human child grows therefrom, with all its members like another child, which is born of a woman, but much smaller.[63]

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486 – 1535).

Agrippa was a German theologian and occult writer influenced by Joachim of Fiore. In 1510 the king sent Agrippa on a diplomatic mission to England, where he was the guest of the Humanist and Platonist John Colet, dean of St Paul’ s Cathedral, and where he replied to the accusations brought against him by Jean Catilinet as a “Judaizing heretic.”[64] In his reply he argued that his Christian faith was not incompatible with his appreciation for Jewish thought, writing “I am a Christian, but I do not dislike Jewish Rabbis.” Agrippa followed Maximilian to Italy in 1511, where came into contact with Agostino Ricci and perhaps Paolo Ricci, and studied the works of philosophers Ficino and Pico, and the Kabbalah. He took part in the schismatic Council of Pisa (1512), but his loyalty to the Catholic Church was attested by a letter in the secretary of Pope Leo thanked him and acknowledges his orthodox position.

In his book De Occulta Philosophia (“On the Occult Philosophy”) published in 1531–1533, Agrippa, mentioned the Templars in connection with the survival of Gnosticism, and thus, according to Michael Haag, “thrust the order into the phantasmagoria of occult forces which were subject of the persecuting craze for which the Malleus Maleficarum was a handbook.”[65] Agrippa’s study of Reuchlin first inspired him in the project of a radical restoration of magic. In 1509-1510, he discussed the idea with Trithemius, to whom he dedicated the first draft of his De occulta philosophia, Agrippa’s most notorious work, his masterpiece, and the one which gave rise to his reputation as a black magician. It is a systematic synthesis of occult philosophy, acknowledged as a significant contribution to the Renaissance philosophical discussion concerning the powers of ritual magic, and its relationship with religion. The second book discusses number symbolism, mathematics, music and astrology as relevant to the celestial world. The third book is largely Christian-Kabbalistic, focusing on angelology and prophecy. Magic, to Agrippa is the most perfect science by means of which one may come to know both nature and God. Agrippa wrote in a chapter about the validity of numerology that, “The [use of a] number [system]… leads above all to the art of genuine prophecy, and the abbot Joachim himself has achieved his prophecies through no other way than through numbers.”[66]

Jesuits

Portrait of a Jesuit and His Family by Marco Benefial (1684-1764)

Ignatius of Loyola (1491 – 1556)

It was in the city of Venice that the men who were to become the primi patres of the Society would meet with the Spanish theologian Ignatius of Loyola (1491 – 1556) prior to founding the society, the most effective of the new Catholic orders. The city was governed by the Great Council, which was made up of members of the noble families of Venice, who elected a “Doge,” or duke, who usually led the council until his death. Although the city’s inhabitants generally remained orthodox Roman Catholics, the state of Venice abstained from the Church’s religious controversies during the Counter-Reformation, leading to frequent conflicts with the Papacy.

Marranos were also involved in the society’ founding. Loyola had been a member of a heretical sect known as the Alumbrados, meaning “Illuminated,” which was composed mainly of Conversos.[67] Although there is no direct evidence that Loyola himself was a Marrano, according to “Lo Judeo Conversos en Espna Y America” (Jewish Conversos in Spain and America), Loyola is a typical Converso name.[68] As revealed by Robert Maryks, in The Jesuit Order as a Synagogue of Jews, Loyola’s successor Diego Laynez was a Marrano, as were many Jesuit leaders who came after him.[69] In fact, Marranos increased in numbers within Christian orders to the point where the papacy imposed “purity of blood” laws, placing restrictions on the entrance of New Christians to institutions like the Jesuits.

Jesuits believed that Joachim of Fiore had prophesied the coming of their society.[70] Loyola himself had also received visions, after which he resolved to begin a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to “kiss the earth where our Lord had walked.”[71] Loyola believed that his plan was confirmed by a vision of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus he experienced one night.[72] Loyola was also delighted with the experience of a series of visions of “a form in the air near him and this form gave him much consolation because it was exceedingly beautiful… it somehow seemed to have the shape of a serpent and had many things that shone like eyes, but were not eyes.”[73] He came to interpret this vision as diabolical in nature.[74]

Loyola visited Venice for the first time in 1523 to embark on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Loyola returned to the city in 1535 with a group of friends who already called themselves the Society of Jesus, and were there ordained as priests. It took just two years for the group to fully establish themselves in the lagoon of Venice and to gain a large following. In March 1537, the whole group went to Rome—all except Ignatius, who worried that he would receive a hostile reception there—to request from Pope Paul III, permission for the Jerusalem journey. The pope gave them a commendation and, bypassing the usual canonical rules and procedures, he permitted them to be ordained priests. These initial steps led to the official founding of the society in 1540.[75]

By his own admission, Loyola, who was a nobleman who had a military background, modeled his new order on the Templars, resurrecting the ideals of the warrior-monk.[76] Ignatius’ plan of the order’s organization was approved by Pope Paul III in 1540 by the bull Regimini militantis ecclesiae (Latin for “To the Government of the Church Militant”), which gave a first approval to the Society of Jesus, also known as the Jesuits, but limited the number of its members to sixty. The bull contained the “Formula of the Institute,” the founding document of the Society, which called on “Whoever desires to serve as a soldier of God beneath the banner of the Cross in our Society.” Loyola was chosen the first Superior General of the society, which was consecrated under the patronage of Madonna Della Strada, a title of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Francis Borgia (1510 – 1572)

Seven years after papal approbation of the Society, the Inquisitor of Rome was still accusing Jesuits of being Illuminati, sodomites, heretics, and abusers of the confessional.[77] He expressed his hope that Loyola “unless worldly considerations interfered with a righteous judgment” would be burned at the stake.[78] On their journey from Paris to Venice, Loyola and his companions were joined by Antonia Arias and Miguel Landivar and who were both of dubious character, but Loyola took him under his trust. In September of 1537, shortly before he and others left for Rome, Ignatius received a letter from Landivar informing him that Arias had taken residence in the home of a pious widow, where he scandalized her by stealing an expensive book “of secrets” and then inviting men into his room for sex.[79] According to English poet Thomas Gray (1716 – 1771), on his visit to Alexander Pope in England, Pope’s mother inquired about Voltaire’s poor health, after which he remarked, “Those damned Jesuits, when I was a boy, buggered me to such a degree that I shall never get over it as long as I live.”[80]

In 1554, Loyola named Francis Borgia (1510 – 1572) commissary general of the Spanish provinces, who was also eventually chosen general of the society in 1565, and canonized in 1670 by Pope Clement X. Borgia was a great-grandson of Pope Alexander VI. Francis’ mother was Juana, daughter of Alonso de Aragón, Archbishop of Zaragoza, who was the illegitimate son of Ferdinand II of Aragon. Francis began his career in Spain as a favorite of his cousin, the Emperor Charles V, and married a Portuguese aristocrat in 1529. Borgia joined the Jesuits in 1546 and in 1550 he went to Rome, where he was received by Loyola, and vastly increased the Society’s reach. His successes during the period 1565-1572 were such that he has been called the society’s second founder.[81] He established a new province in Poland, new colleges in France and initiated Jesuit missionary work in the Americas. In 1565 and 1566 he founded the missions of Florida, New Spain, and Peru. His emissaries visited Brazil, India and Japan.

Borgia became a caballero (“knight”) of the Order of Santiago in 1540, while some of his brothers were caballeros of Santiago and of the Valencian Order of Montesa, who regarded themselves as Templars.[82] Francis Borgia’s brother, Don Pedro Luis Galceran de Borgia, who was arrested on charges of sodomy in 1572, was a Grand Master of the Order of Montesa, whose members considered themselves Templars.[83] In 1565, Borgia, as the newly elected Superior General, sent a group of Jesuits with the army that was put together to relieve Malta from the Great Siege. As Emanuel Buttigieg indicated, the Jesuits and the military-religious Order of Malta, held “a relationship characterized by shared aims and extensive co-operation, as well as by highly critical voices from within the Order of Malta at the perceived over-bearing influence.”[84] Originally known as the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, or Knights Hospitaller, they were a medieval Catholic military order, who inherited the wealth and properties of the Templars after that order was disbanded. It was headquartered variously in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, Rhodes and Malta, until it became known by its current name. After seven years of moving from place to place in Europe, the knights gained fixed quarters in 1530 when Charles I of Spain, as King of Sicily, gave them Malta.

Juan Rodríguez Juárez (1675-1728), “The Virgin of Carmel With St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross.”

Francis Borgia was a confessor to the famous Spanish mystic Saint Teresa of Avila (1515 – 1582), who with Saint John of the Cross established the Discalced Carmelites in 1593. In Europe, Marranos joined orders like the Franciscans, Dominicans and Discalced Carmelites, where their prophetic eschatology, which advanced the millennial conceptions of Joachim of Fiore, was often branded as heresy.[85] John of the Cross was born Juan de Yepes y Alvarez, into a Marrano family.[86] John’s mystical theology is influenced by the Neoplatonic tradition of pseudo-Dionysus, a Christian theologian and philosopher of the late fifth to early sixth century.[87] The author pseudonymously identifies himself as the figure of Dionysius the Areopagite, the Athenian convert of the apostle Paul. The Dionysian mystical teachings were universally accepted throughout the East, amongst both Chalcedonians and non-Chalcedonians, and also had a strong impact in later medieval western mysticism, most notably that of Meister Eckhart. Based upon preliminary reports made by members of the Discalced Carmelite mission in Basra during the sixteenth century, the Mandaeans of Iraq are called “Christians of Saint John.”[88] Teresa of Avila’s paternal grandfather, Juan Sánchez de Toledo, was a Marrano.[89] During a bout of severe illness, Teresa experienced periods of religious ecstasy. Around 1556, when various friends suggested these were diabolical, Francis Borgia reassured her of their divine inspiration.

In the wake of the Counter-Reformation, new religious orders established themselves in Malta with the support of the Order and individual Hospitallers. The Jesuits rapidly attained a position of prominence within Malta, where they ministered to the Maltese native population, the Muslim slave population, as well as members of the Knights of Malta. Already in Loyola’s time, from 1553, the bishop of Malta, Dominic Cubelles, began repeatedly asking Loyola to send some members to Malta so as to help reform the diocese and the ruling Knights of Malta, as well as to start a Jesuit College. Loyola recognized the potential of using Malta as a base to send Jesuits to Girba, near Tripoli. Given Malta’s geographic location, and the proximity of the Maltese language to Arabic, Malta seemed to Loyola an ideal spot for the training of missionaries for the Muslim world.[90] With their expansion across the world, concerns over the Jesuits’ growing influence often led to open resistance, and even expulsion. Such expulsion of the Jesuits, either temporary or final, was a regular occurrence. Instances included: Antwerp (1578), much of France (1594-1603), Venice (1606), Japan (1614), Prague and Bohemia (1618), Hungary (1619), Naples and the Southern Netherlands (1622), Ethiopia (1634), Brazil (1641, 1661), Russia (1676), and China (1724), along with other missionaries.[91]

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563.

In addition to the Protestant Reformation, the challenges inherited by the Medici pope, Clement VII, included an immense power struggle in Italy between Europe’s two most powerful kings, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Francis I of France, each of whom demanded that he choose a side, and Ottoman invasions of Eastern Europe led by Suleiman the Magnificent. Clement VII’s problems were exacerbated contentious divorce of King Henry VIII of England, knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, Charles V’s aunt, Catherine of Aragon, the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella—resulting in England breaking away from the Catholic Church, to form the Church of England. The Protestant subversion precipitated in the Counter-Reformation, the period of Catholic resurgence initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation, beginning with the Council of Trent (1545 – 1563)—convened by Pope Paul III, born Alessandro Farnese—and ending at the close of the Thirty Years’ War (1648).

By the end of the Counter-Reformation, all hope of conciliating the Protestants was lost and the Jesuits became a powerful force.[92] Despite intense opposition in the Curia, it was Cardinal Gasparo Contarini (1483 – 1542) who succeeded in convincing Pope Paul III to approve the Society of Jesus, and he is in part responsible for the bull Regimini militantis ecclesiae.[93] Contarini was born in Venice, the eldest son of Alvise Contarini, of the ancient noble House of Contarini. In 1541, Contarini took part in the adjustment proceedings at the Conference of Regensburg. The Colloquy of Regensburg, historically called the Colloquy of Ratisbon, was a conference held at Regensburg (Ratisbon) in 1541, during the Protestant Reformation, which marks the culmination of attempts to restore religious unity in the Holy Roman Empire by means of theological debate between the Protestants and the Catholics. The subject for debate was to be the Augsburg Confession and the Apology of the Augsburg Confession written by Philip Melanchthon. It was Contarini who led to the stating of a definition in connection with the article of justification in which occurs the famous formula “by faith alone are we justified,” with which was combined, however, the Roman Catholic doctrine of good works. At Rome, this definition was rejected in the consistory of May 27, and Luther declared that he could accept it only provided the opposers would admit that hitherto they had taught differently from what was meant in the present instance.

Cardinal Gasparo Contarini (1483 – 1542)

In Italy, Loyola and his followers were most warmly welcomed by a group influenced by the humanistic movement, who are sometimes referred to as “the Catholic evangelicals” or the Spirituali, of which Contarini was a member.[94] The Spirituali were the leaders of the movement for reform within the Roman church, who took many of their ideas from older Catholic texts, but certainly found inspiration in the Protestant Reformation, especially Calvinism. The Spirituali included Cardinal Jacopo Sadoleto (1477 – 1547), Cardinal Reginald Pole (1500 – 1558), Italian poet Vittoria Colonna, and her friend, the artist Michelangelo. Pietro Bembo, Luigi Alamanni, Baldassare Castiglione and Marguerite de Navarre were among Colonna’s literary friends. Pietro Bembo (1470 – 1547) was an Italian scholar, poet who had a love affair with Lucrezia Borgia. Bembo accompanied Giulio de’ Medici to Rome, where he was soon after appointed Latin secretary to Pope Leo X. In 1514, he became a member of the Knights Hospitaller, now known as the Knights of Malta.[95] In 1542, Bembo become a cardinal after being named by Pope Paul III.

Cardinal Reginald Pole (1500 – 1558)

Reginald Pole was an English cardinal of the Catholic Church and the last Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, then papal legate to Mary Tudor’s England. Pole was a Plantagenet and great-nephew of kings Edward IV and Richard III. In 1521, Pole went to the University of Padua, where he met leading Renaissance figures, including Bembo, and various Catholic leaders associated with Paul III and the Jesuits. Pole corresponded with Erasmus who introduced to him the Polish scholar John à Lasco.

Assisted by Bishop Edward Foxe (c. 1496 – 1538), Pole represented Henry VIII in Paris in 1529, researching general opinions among theologians of the Sorbonne about the annulment of Henry’s marriage with Catherine of Aragon, so he could marry his mistress Anne Boleyn.[96] Cranmer, who was Pole’s successor as Archbishop of Canterbury, along with Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the king’s Lord Chancellor, Thomas Cromwell, Richard Rich, and Thomas More, the author of Utopia, all figured prominently in Henry VIII’s administration. Towards the end of 1529, an Englishman, Richard Croke (c. 1489 – 1558), a follower of Erasmus, travelled to Venice on a secret mission, which seems to have been the idea of Cranmer, who had proposed to Henry VIII that he should consult canonist lawyers and leading Jewish rabbis as to the legality of his proposed divorce. As Henry questioned the legality of his marriage to Catherine on the grounds that she was his brother’s widow, the advice of the rabbis was required because different views as to the legality of marriage with a brother’s widow are found in the Old Testament.[97]

Catherine of Aragon, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella, pleads her case against divorce from Henry VIII.

Croke consulted the leading theologian of Venice, expert in Hebrew studies and in touch with Jewish scholars, the Franciscan friar Francesco Giorgi (1466 – 1540), one of the most famous of the Italian Christian Cabalists, as the author of De harmonia mundi. As a member of the patrician Zorzi family, Giorgi had contacts with Venetian government circles as Contarini, and was entrusted with missions of number of delicate missions.[98] “Giorgi’s Cabalism,” explained Yates, “though primarily inspired by Pico, had been enriched by the new waves of Hebrew studies of which Venice, with its renowned Jewish community was an important centre.”[99] Like Pico, he saw correspondences between the Kabbalah and the teachings of the Hermes Trismegistus, which he lent a Christian interpretation. These influences were integrated into Giorgi’s Neoplatonism in which was included the whole tradition of Pythagoro-Platonic numerology, even of Vitruvian theory of architecture, which, for Giorgi was connected with the Temple of Solomon.[100] Giorgi was also briefly in contact with Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa.[101] For Giorgi, Saturn does not have the negativity and melancholy typically associated with it, but is the “revalued” Saturn of the Renaissance, the star profound intellectual insight. The Saturnian religion, says Giorgi, is the one from which all others derive, and those who have received its fullest inspiration are the Hebrews.[102] “Saturnians” are not the unfortunate souls of traditional astrology but aspirants who contemplate the highest truths.[103]

As Yates pointed out, the mission to Venice to consult with its Jewish rabbis and Kabbalists was an odd maneuver considering that Jews were not allowed in England at the time.[104] As a member of the patrician Zorzi family, Giorgi had contacts with such Venetian government circles as the Contarini, and was entrusted with a number of delicate missions.[105] Giorgi enthusiastically assisted Croke, taking trouble to procure books and documents bearing on the case. There are letters from Henry VIII himself thanking Giorgi for his valuable assistance.[106]

The affair ultimately led to the English Reformation and the establishment of the Church England, which separated itself from the Catholic Church in Rome. Pope Clement VII, considering that Henry VIII’s earlier marriage had been entered under a papal dispensation, and how Catherine’s nephew Emperor Charles V might react to such a such a decision, rejected the annulment. At that time, the Pope was prisoner of Charles V following the Sack of Rome in 1527. Eventually, Henry VIII, although otherwise theologically opposed to Protestantism, took the position of Protector and Supreme Head of the English Church and Clergy to ensure the annulment of his marriage. He was excommunicated by Pope Paul III in 1533. Ten Articles were adopted by clerical Convocation in 1536 as the English Church’s first post-papal doctrinal statement. The first five articles were based on the Wittenberg Articles negotiated between English ambassadors Edward Foxe, Nicholas Heath and Robert Barnes and German Lutheran theologians, including Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon. This doctrinal statement was itself based on the Augsburg Confession of 1530.[107]