6. Eastern Mystics

Dark Ages

The idea of the Dark Ages was by European scholars contrived to account for the supposed break between classical and later European civilization, a notion based on the false supposition that the Greeks and Romans were somehow the ancestors of the Europeans. According to Janet L. Abu-Lughod, in Before European Hegemony, the “fall of Rome” was a gradual process and did not effect all parts of the Empire equally. Therefore, the “Dark Ages,” refers exclusively to Northwestern Europe.[1] Europe had traditionally served as a ready source of slaves who worked the large agricultural estates of the Romans. The weakening of the Roman Empire allowed European tribes among the Gauls, Vandals and Visigoths to finally launch successful invasions. It had been these northern “barbarians” who had been responsible for nearly extinguishing the light of the Roman Empire, when the Visigoths, under Alaric, sacked Rome in 410 AD.

Modern Europeans are not direct inheritors of classical civilization. Contrary to popular belief, the arts and sciences of antiquity were introduced to them to them by way of the Muslims. During the early Middle Ages, a new power appeared on the scene, a threat that would ultimately contribute to the Crusades. The impetus behind this great expansion of the Arabs, that led to the collapse of the Persian Empire, and seizure of much of the territories of the former Roman Empire, was the religion of Islam, revealed to Mohammed in the seventh century AD. The capital of the Roman empire had already been transferred to Constantinople, in the eastern arm of the empire, known as Byzantium. In the East, the Persian empire continued to dominate. In the third century AD, the Parthians, weakened by repeated Roman invasions, were replaced by the Sassanians, an Iranian dynasty who extended the empire’s boundaries, and challenged Roman power in the Middle East.

Following Mohammed’s death in 632 AD, the spread of Islam continued at a very rapid pace. A series of famous Caliphs, meaning successors, named Abu Bakr, Omar, Uthman and Ali, united the Arab clans for great raids into Syria and Mesopotamia. Within an amazingly short period of time, the Muslims completely conquered the Persian Empire of the Sassanids, Egypt, and though unable to take the city of Constantinople itself, stripped the Byzantine Empire of its eastern provinces. The Arabs also extended Islam eastward to the Indus River and the frontiers of China, and westward into North Africa, and toward the end of the century, Byzantine rule over the coast of Africa was ended by a maneuver which drove the Greeks from Carthage.

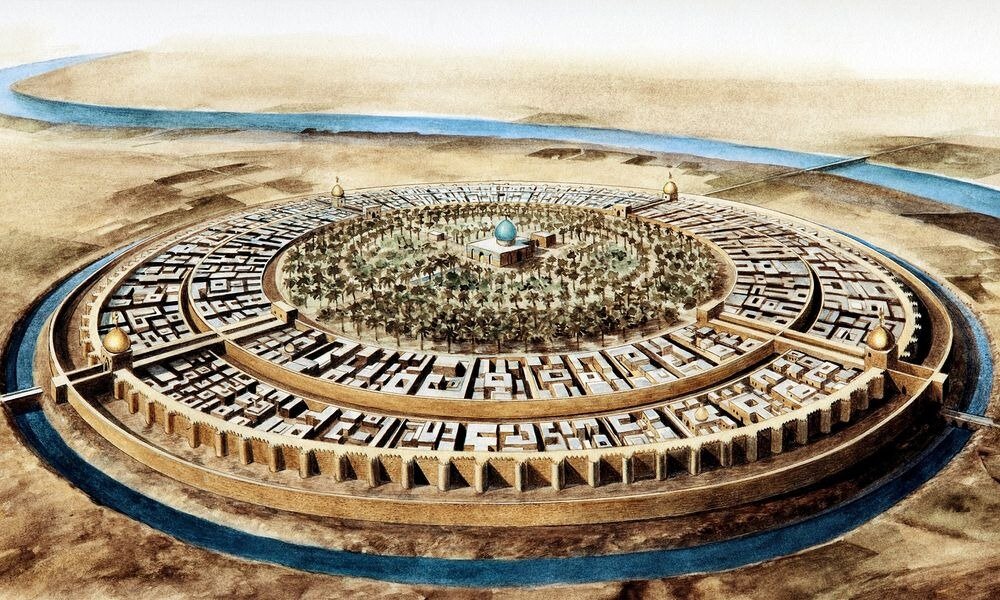

The original core of the city of Baghdad is the round city of Baghdad, constructed in ancient times by the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur in AD 762–766 as the official house of the Abbasid.

By defeating Ali, the fourth Caliph, Muawiyah became successor and transferred the seat of authority from Mecca to Damascus, placing the caliphate firmly in the hands of the Umayyad family. Opposition accelerated against the Umayyads, who were finally overthrown by the Abbasids, led by Abu al-Abbas, a descendant of an uncle of the prophet Mohammed. It was at the end of Abbas’ reign, with the accession to the caliphate in 754 AD of his brother, Abu Jafar, that the true inauguration of the great era of Arab rule began. This ancestor of the next thirty-five caliphs took the title of al-Mansur, meaning “rendered victorious”. In 762-766 AD, al-Mansur built a new capital at Baghdad near the site of the ancient city of Babylon. From the corners of the known world royal embassies came bearing gifts and seeking the favor of the Caliph of Baghdad. This was the world that produced the Arabian Nights, tales replete with magical and occult lore, through which the magnificence of the court at Baghdad of al-Mansur’s successor Harun al-Rashid became renowned in the West.

The splendor of the Abbasid regime was enhanced by their generous patronage of artists and artisans of all kinds. Many of the arts and techniques of handicraft of China, India, Iran, and the Byzantine Empire, and those of the early civilizations of Greece, Egypt and Mesopotamia were studied by the Arabs. From the Greek philosophers, the Muslim scholars, writing in Arabic, created a school of philosophy that had a profound and recognized influence on Christian philosophers of medieval Europe. By the middle of the ninth century the main works of Aristotle, Plato, Euclid, Ptolemy, Hippocrates, Galen, and Hermetic works, had been translated into Arabic.

Sabians

Harran, ancient Carrhae, was a major ancient city in Upper Mesopotamia whose site is near the modern village of Altınbaşak, Turkey, 44 kilometers southeast of Şanlıurfa.

Some say that, following the closing of their Platonic Academy in Athens in 529 AD by the emperor Justinian, the last of the Neoplatonists moved east, seeking temporary refuge at the court of the King Khosrow I of Persia (512–514 – 579 AD), though, finding their situation inhospitable, departed from Persia to Harran, where they joined the Sabians, another important school of translators of Greek works into Arabic, though primarily interested in mathematical and astronomical works.[2] Sometime at the end of the Neo-Sumerian Empire (circa 2000 AD), there was built a temple of Sin, the god of the moon and planet in the Mesopotamian religions of Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia and Aram, who was worshipped Harran into the Islamic period. Haran first appears in the Book of Genesis as the home of Terah and his descendants, and as the temporary home of his son Abraham, from where his nephew Lot, and Abraham’s wife Sarah planned their journey from Ur of the Chaldees to the Land of Canaan.

Harran, originally known as Carrhae, was less than a hundred miles from Samosata, the capital of Commagene, and belonged to the Roman province of Osrhoene. The city was called Hellenopolis in the Early Christian period. It is mentioned, in Moses of Khoren’s and Mikayel Chamchian’s History of Armenia, as being under the authority of Helena of Adiabene, who had converted to Judaism and moved to Jerusalem where she became allied with the House of Herod.[3] Harran was originally governed by descendants of the daughter of Helena’s son, Izates II, who had also converted to Judaism.

The Sabians of Harran are often considered to be the same as, or related to, the Gnostic community of the Mandaeans.[4] E.S. Drower has suggested that the parallels between the Mandaean and Kabbalistic ideas reflect a common Gnostic origin, a “subterranean stream of ideas which emerges” in a variety of religious movements.[5] Nathaniel Deutsch, in The Gnostic Imagination: Gnosticism, Mandaeism and Merkabah Mysticism, recognizes that “at present, we must be satisfied with acknowledging the phenomenological parallels between the Mandaean and Kabbalistic traditions, although we must also seriously consider the possibility that both Mandaean and Kabbalistic sources drew on a common pool of earlier (Jewish?) theosophic traditions.”[6]

The Sabians, according to Daniel Chwolson (1819 – 1911 AD), author of a monumental work, Die Ssabier, retained a mixture of Babylonian and Hellenistic religion, superposed with a coating of Neoplatonism.[7] As Majid Fakhry has explained, in A History of Islamic Philosophy:

Their religion, as well as the Hellenistic, Gnostic, and Hermetic influences under which they came, singularly qualified the Harranians to serve as a link in the transmission of Greek science to the Arabs and to provide the ‘Abbasid court from the beginning of the ninth century with its greatly prized class of court astrologers.[8]

The Sabians identified themselves deceptively to the Muslim authorities with the “Sabeans” of the Quran, to gain the protection of the Islamic state as “People of the Book.” According to al-Biruni, a Muslim scholar of the eleventh century, the Sabians were originally the remnant of Jews exiled at Babylon, where they had adopted the teachings of the Magi. These, he believes, were the real Sabians. However, he indicates, the same name was applied to the so-called Sabians of Harran who derived their system from Agathodaemon, Hermes, Walis, Maba, Sawar.[9] In reality, the Sabians inherited the traditions of similar Jewish-Gnostic sects like the Hypsistarians in nearby Cappadocia, and transmitted the traditions of Neoplatonism and Hermeticism to the Islamic world. They worshipped the planets, and were reputed to sacrifice a child, whose flesh was boiled and made into cakes, which were then eaten by a certain class of worshippers.[10]

The Emerald Tablet of Hermes

Ibn al-Nadim (d. 990), an Arab Muslim scholar and bibliographer, listed under alchemy the “scientific” texts the Sabians composed to convey the revelations of their prophets Agathodemon and Hermes, whom the Sabians identified with Seth and Enoch.[11] Alchemy, which derived from Hermeticism, was transmitted to Europe via the Muslims. In the Islamic world, the influence of the Hermetic teachings of the Sabians helped to shape the pursuit of chemistry among the Muslim scientists, which was studied mostly in connection with alchemy. According to Seznec, “thanks to the Crusades, and to the penetration of Arab philosophy and science into Sicily and Spain, Europe came to know the Greek texts with their Arab commentaries, in Latin translations for the most part made by Jews. The result was an extraordinary increase in the prestige of astrology, which between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries enjoyed greater favor than ever before.”[12]

Even the name alchemy affirms the Arabic origin of chemistry, being derived from the Arabic term al-kimiya. The greatest Arabic alchemist was ar-Razi, a Persian physician who lived in Baghdad in the late ninth and early tenth century, who drew his central concepts from the Sabians. The most famous was Jabir ibn Hayyan, known to the West as Geber, from whom we derive the word “gibberish.” Jabir’s works, which were translated into Latin in the twelfth century AD, proved to be the foundation of Western alchemists and justified their search for the “philosopher’s stone.” But during the ninth to fourteenth centuries, alchemical theories faced criticism from a variety of practical Muslim chemists, including al-Kindi, al-Biruni, Avicenna and Ibn Khaldun, who wrote refutations against the idea of transmuting metals.

The Arabs’ fascination with alchemy was founded on a work called the Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus, not known during the Hellenistic era. The Emerald Tablet comes from a larger work called Book of the Secret of Creation, which exists in Latin and Arabic manuscripts, and was attributed to Apollonius of Tyana, called Balinus by the Arabs. The Arabs identified Hermes with a prophet mentioned in the Qoran, named Idris, equated with the prophet Enoch of the Bible. Just as Hermes came to be identified with Enoch, Seth, the son of Adam, was identified with Agathodaimon, who engraved on stone the names of the months, years and constellations, with the assistance of an angel of God.[13] Seth passed on his wisdom to Zoroaster, and from him to Pythagoras, Empedocles, Plato, Aristotle and the Neoplatonists. Hermes, like Seth, was said to have inscribed his knowledge on two pillars, and Herodotus described the pillars of the Phoenician Hercules: “one was of pure gold; the other was as of emerald which gleamed in the dark with a strange radiance.”[14]

Brethren of Sincerity

Arabic manuscript illumination from the 12th century AD showing the Brethren of Purity

The Sabians were an important influence on the fifty-two treatises of the Ikhwan al Safa wa Khullan al Wafa, or “The Brethren of Sincerity and Loyal Friends,” a brotherhood that flourished in the city of Basra in Iraq, which was an important source of inspiration for much of Sufi tradition, as well as Jewish scholars of Kabbalah.[15] It is also generally agreed that the Epistles of the Ikhwan al Safa wa Khullan al Wafa were composed by leading proponents of the Ismailis, a sect of the Shia.[16] According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, the Shia sect was founded by a Yemeni Jew named Abdallah ibn Saba who embraced Islam. When Mohammed’s son-in-law Ali (601 – 661 AD) became Caliph, Abdallah ascribed divine honors to him whereupon Ali banished him. After Ali’s assassination, Abdallah is said to have taught that Ali was not dead but alive, that a part of the Deity was hidden in him and that after a certain time he would return to fill the earth with justice. Until then, the divine character of Ali was to remain hidden in the Imams, who temporarily filled his place. As the Jewish Encyclopedia notes, “It is easy to see that the whole idea rests on that of the Messiah in combination with the legend of Elijah the prophet.”[17] This office of Imam was thought among the Shia to have been passed on directly from Ali to the sixth Imam, Jafar as-Sadiq (700 or 702 – 765 AD), and then on through to the twelfth Imam, who disappeared in 873 AD. The Shia majority, following twelve Imams, were known as Twelvers. Some of Jafar’s followers, however, remained loyal to his son Ismail, and were known as Ismailis, or Seveners.

Though the Epistles drew on multiple traditions, they attributed to them a common origin, echoing Aristobulus in tracing Greek philosophy to Jewish roots.18 Pythagoras, according to the Epistles, was a “monotheistic sage who hailed from Harran.”[18] The Epistles of the Brethren of Sincerity were a philosophical and religious encyclopedia, which scholars regard as reflecting elements of Pythagorean, Neoplatonic and Magian traditions drawn up in the tenth century AD. The Neoplatonic theory of creation by emanation from a single creator, together with the notion that all creation was organized according to a hierarchical pattern was a dominant theme in the Epistles. Their stated purpose, following Gnostic tradition, was to teach initiates how to purify their souls of bodily and worldly attachments and ascend back to the divine source from which they came.

The Brethren of Sincerity followed the Sabians in revering Idris, the Muslims’ name for the prophet Enoch, whom they equated with Hermes, identified in the Kabbalah with Metatron. The Brethren regularly met on a fixed schedule, on three evenings of each month, in which speeches were given, apparently concerning astronomy and astrology, and the recitation of a hymn, which was a “prayer of Plato,” “supplication of Idris,” or “the secret psalm of Aristotle.” During their meetings and possibly also during the three feasts they held, on the dates of the sun’s entry into the Zodiac signs of Ram, Cancer, and Balance, they engaged in a liturgy reminiscent of the Sabians.[19] The Epistles also boasted that, along with representatives of all walks of society, their order also consisted of “philosophers, sages, geometers, astronomers, naturalists, physicians, diviners, soothsayers, casters of spells and enchantments, interpreters of dreams, alchemists, astrologers, and many other sorts, too many to mention”[20]

Assassins

Assassin fortress of Alamut. Persian miniature.

It was an alleged member of the Brethren of Sincerity, Abdullah ibn Maymun who in about 872 AD succeeded in capturing the leadership of the Ismaili sect of Shia Islam, whose ideas derived originally from the Sabians. Ibn Maymun, who has been variously described as a Jew, as a follower of the Mesopotamian Gnostic heretic Bardasanes, and, most commonly, as a Zoroastrian dualist, was brought up on Gnosticism, but was well versed in all religions. In occult history, the Ismailis were regarded as important for having produced the cult of the Assassins, who were supposedly responsible for transmitting their occult teachings to the West.

The Assassins were founded by Hassan-i Sabbah (c. 1050 – 1124 AD), also known as Sheikh al Jabal, or “Old Man of the Mountain.” His order was called in Arabic “Hashishim,” because they supplied hashish (or marijuana) to their recruits for brainwashing purposes. As described by Marco Polo, the Old Man had made, “the biggest and most beautiful gardens imaginable. Every kind of wonderful fruit grew there. There were glorious houses and palaces decorated with gold and paintings of the most magnificent things in the world. Fresh water, wine, milk and honey flowed in streams. The loveliest girls versed in the arts of caressing and flattering men played every musical instrument, danced and sang better than any other women.”[21] The Old Man would induce his dupes fall asleep so that when they awoke they would find themselves in this garden, which he persuaded them was the Paradise described by Mohammed. Thus assured of its existence, they were willing to risk their lives on any mission assigned to them.

According to Edward Burman, author of the Assassins: Holy Killers of Islam, the two great Assassin Grand Masters, Hasan-i Sabbah and Rashid al-Din Sinan (1131 or 1135 – 1193 AD), both have close links with the Epistles of the Brethren of Sincerity. Rashid, chief of the Syrian Assassins and original “Old Man of the Mountains,” made use of the writings in the Brethren of Sincerity, while in the eighth epistle of the second section there is a spiritual portrait of the ideal man is a close description of Hasan-i Sabbah: “Persian in origin, Arab by religion, Iraqi by culture, Hebrew in experience, Christian in conduct, Syrian in asceticism, Greek by the sciences, Indian by perspicacity, Sufi by his way of life, angelic by morals, divine by his ideas and knowledge, and destined for eternity.”

In the late eleventh century, led by Hassan-i Sabbah, the Assassins established a castle at Alamut, or the Eagle’s Nest, a fortress stronghold in Persia. The Assassins waged an international war of terrorism against anyone who opposed them, but eventually turned on each other. Finally in 1256 AD, the conquering Mongols, lead by Mangu Khan, swept over Alamut and annihilated them. Nevertheless, the leaders of the Assassins survived through a hereditary line represented by the Agha Khans today.

Sufis

Muslim sage Al-Khidr

The Epistles of the Brethren of Sincerity, which contributed to the popularization of Neoplatonism in the Arabic world, had a great influence on Islamic mysticism and philosophy. The Sabians, acting as translators and astrologers, were responsible for infecting the Islamic world with the occult tradition of philosophy and of contributing to the formation of a mystical version of Islam, known as Sufism. The word “Sufism” is generally agreed to come from the word Suf, referring to the rough woolen garment that the early Sufis wore to demonstrate their ascetic renunciation of worldly desires. Contrary to the claims of the Sufis, asceticism is denounced in the Quran, and has its origins outside of Islam in practices that are common throughout the world. It is found, for instance, in Merkabah Mysticism, the monks of Christianity, the lamas of Buddhism, and the fakirs of Hinduism. Islam, however, aimed to correct these inclinations. A well-known saying of the Prophet Mohammed is “there is no monasticism [asceticism] in Islam.” Of the Christians, the Quran says: “But the asceticism which they invented for themselves, We [God] did not prescribe for them: [We commanded] only the seeking for the Good Pleasure of God.”[22]

It is generally accepted that the first exponent of Sufi doctrine was the Egyptian or Nubian, Dhun Nun, of the ninth century AD, whose teaching was recorded and systematized by al Junayd. The doctrines expressed by al Junayd were then boldly preached by his pupil, ash-Shibli of Khurasan in the tenth century. A fellow-student of ash-Shibli, was al-Husayn ibn Mansur al-Hallaj (c. 858 – 922 AD) whose thought demonstrated some clearly heretical elements, such as reincarnation, incarnation, and so on. He was ultimately put to death by the son of Saladin, the great Muslim leader who recaptured Palestine from the Crusaders, for declaring “I am the truth,” identifying himself with God. However, later Sufi writers nevertheless regard him as a saint and martyr, who suffered because he disclosed the great secret of the mystical union of man and God.

To the Sufis, mystical union is known as Hulul, or the incarnation of God in the human body. While Tawheed, the “oneness” of God, typically refers to the monotheistic creed of Islam, for the Sufis it refers to this mystical union with God. According to al-Hallaj, for example, man is essentially divine because he was created by God in his own image, and that is why he claimed that in the Quran God commands the angels to bow down in “worship” to Adam. As De Lacy O’Leary described, in Arabic Thought and its Place in History:

This is an extremely interesting illustration of the fusion of oriental and Hellenistic elements in Sufism, and shows that the theoretical doctrines of Sufism, whatever they may have borrowed from Persia and India, receive their interpretative hypotheses from neo-Platonism. It is interesting also as showing in the person of al-Hallaj a meeting-point between the Sufi and the philosopher of the Isma‘ilian school.[23]

Sufism is considered a branch of mysticism, the basis of which is considered by scholars to be union between the mystic and God. Therefore, similar to the mysticism of other religions, the experiences of the Sufis usually involve trance states, visions, and other such psycho-spiritual experiences. According to the eminent Muslim historian Ibn Khaldun, the path of the Sufis comprised two directions. The first was founded in the Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad, while the other was corrupted with heretical innovations. Among the deviations addressed by Ibn Khaldun were the beliefs in a Mahdi, whose themes he attributed to Shia influence; the existence of the “Pole” (Qutb) and other members of the spiritual hierarchy; the extravagant theosophical speculations, including magic, astrology and sorcery and pretentions of predicting the future and purported miracles worked by saints and holy men. Lastly, Ibn Khaldun denounced the other-worldliness of Sufi aspirations, which he regarded as a departure from addressing the pressing needs of the here and now exemplified by the earliest generations of Muslims. James Morris explains that Ibn Khaldun was concerned with:

...the much more and down-to-earth consequences of diverting substantial societal and human resources to the pointless, imaginary distractions and pastimes of such large groups of “simpletons,” and the perhaps even more debilitating long-range consequences of their attempting to lead a moral and religious life somehow separate from what they allegedly viewed as the “corrupting” sphere of political and military power and authority.[24]

Sufi practices are merely attempts to attain psychic states—for their own sake—though it is claimed the pursuit represents seeking closeness to God, and that the achieved magical powers are gifts of advanced spirituality. For several reasons, Sufism was generally looked upon as heretical among Muslim scholars. Among the deviations introduced by the Sufis was the tendency to believe the daily prayers to be only for the masses who had not achieved deeper spiritual knowledge, but could be disregarded by those more advanced spiritually. The Sufis introduced the practice of Dhikr, or religious oral exercises, consisting of a continuous repetition of the name of God. These practices were unknown to early Islam, and consequently regarded as Biddah, meaning “unfounded innovation.” Also, many of the Sufis adopted the practice of Tawakkul, or complete “trust” or “dependence” on God, by avoiding all kinds of labor or commerce, refusing medical care when they were ill, and living by begging.

A Sufi teacher called a Sheikh was often elevated to the rank of “saint,” known in Islam as a Wali, or “friend of God.” A Wali is one regarded as enjoying God’s special favor and blessed with the capacity to perform miracles. Called Karamat, they are considered lower in rank than those performed by the prophets. As described by the well-known scholar of mysticism in Islam, Annemarie Schimmel, the cult of saints is permeated with pre-Islamic ideas. Ancient local deities survived as saints whose actual names are sometimes unknown and whose tombs are surrounded by legends. Likewise, in India ancient Hindu sanctuaries have been transformed into Muslim shrines. As in Christian saint worship, many saints specialize in curing specific ailments or help in particular cases, such as infertility, illness, and madness. As Schimmel points out, “Many customs that are practiced near saints’ tombs border on magic, and it is indeed one of the sheikhs’ duties to produce amulets of all sorts. One has amulets (incidentally, our word “amulet” is derived from the Arabic hama’il) for this or that illness, problems during pregnancy and delivery, danger of fire or theft, and so on.”[25]

Al Khidr

Saint George slaying the Dragon in an updated version of the Baal Epic.

While pagan mysticism typically aspires to union with a “god,” a practice which would otherwise be acknowledged in Islam as communication with Jinn, the Sufis avoid all associations by claiming to make contact with the mysterious figure of al Khidr, meaning “the Green One.” Though not mentioned by that name in the Quran, al Khidr is identified with a figure met by Moses. He is referred to as the “Servant of God” and as “one from among Our friends whom We had granted mercy from Us [God] and whom We had taught knowledge from Ourselves.” In the Quran, Moses asks for permission to accompany him that he may learn “right knowledge of what [he has] been taught.”[26] But the name al Khidr is found only in Hadith literature, such as the case narrated by Imam Ahmad in Al-Zuhd, whereby the Prophet Muhammad is said to have stated that Elijah and al Khidr meet every year and spend the month of Ramadan in Jerusalem, and another narrated by Yaqub ibn Sufyan from Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, whereby a man he was seen walking with was actually al Khidr. However, to the Sufis, al Khidr acquired a number of occult associations and, we have to assume, was the disguise assumed by demonic apparitions.

The figure of al Khidr has its equivalent in the cult of Saint George, shared by Christian, Jews as well as Muslims. George’s mother was from Lydda, Palestine, but he was a Cappadocian born in Cilicia, the heartland of the Mithraic Mysteries during Hellenistic times, and whose capital city of Tarsus was the birthplace as well of the apostle Paul.[27] Historians note that the origin of Saint George is in Cappadocia and is similar to the ancient god named Dionysus-Sabazios, who was usually depicted riding on horseback.[28] The legend of Saint George killing a dragon is not a Christian story at all, but is a Christian adaptation of the typical duel of the Middle Eastern dying-god, like Baal, against the Sea-Dragon, or Zeus against Typhon the Titan. According to historian E. A. Wallis Budge:

I doubt much of the whole story of Saint George is anything more than one of the many versions of the old-world story of the conflict between Light and Darkness, or Ra and Apepi, and Marduk and Tiamat, woven upon a few slender threads of historical fact. Tiamat, the scaly, winged, foul dragon, and Apepi the powerful enemy of the glorious Sungod, were both destroyed and made to perish in the fire which he sent against them and their fiends: and Dadianus, also called the “dragon”, with his friends the sixty-nine governors, was also destroyed by fire called down from heaven by the prayer of Saint George.[29]

There is a tradition in the Holy Land of Christians and Muslims going to an Eastern Orthodox shrine of Saint George at Beith Jala, with Jews also attending the site in the belief that the prophet Elijah was buried there. These Muslims worshipped this same Saint George or Elijah as the Sufi figure of al Khidr, a tradition which was found throughout the Middle East, from Egypt to Asia Minor.[30] The figure of al Khidr originated most likely from Jewish legends and is associated with the Muslim Mahdi, in the same way that the prophet Elijah is associated with the Jewish Messiah.[31] According to the Book of Kings, Elijah defended the worship of the one God over that of the Phoenician god Baal. Elijah, like Enoch, did not die but is believed to have ascended directly to heaven. Some of the earliest sources on Sandalphon, an archangel in Jewish and Christian writings, refer to him as the prophet Elijah transfigured and elevated to angelic status. Other sources, mainly from the Midrashic period, describe Sandalphon as the “twin brother” of Metatron, whose human origin as Enoch was similar to the human origin of Sandalphon. In Kabbalah, Sandalphon is the angel who represents the Sephiroth of Malkhut and overlaps, or is confounded with, the angel Metatron. Elijah is an important figure of the Kabbalah, where numerous leading Kabbalists claimed to preach a higher knowledge of the Torah directly inspired by the prophet through a “revelation of Elijah” (gilluy ‘eliyahu).

Qutb

The Brethren of Sincerity exercise an important influence on the famous Sufi mystic, Muhyiddin Ibn Arabi (1165 – 1240 AD), and was transmitted as far as Al-Andalus, or Moorish Spain, where they would have a profound influence on Jewish Kabbalah. Although Ibn Arabi is widely regarded among Sufis as al-Sheikh al-Akbar (“The Greatest Sheikh”), he was consistently denounced as an apostate by orthodox scholars. Imam Burhan al-Din al-Biqa‘i (d. 885) wrote a book titled Tanbih al-Ghabi ila Takfir Ibn ‘Arabi wa Tahdhir al-‘Ibad min Ahl al-‘Inad (“Warning to the Ignoramus Concerning the Declaration of Ibn Arabi’s Disbelief, and Cautioning the Servants of Allah Against Stubborn People”) in which he quotes many Fatwas (Islamic rulings) by scholars from different Madhhabs criticizing Ibn Arabi. The famous Meccan historian Taqi al-din al-Fasi (1373 – 1429 AD) in massive biographical dictionary, al-‘lqd al-thamin (“The Precious Necklace”) also collected the legal opinions issued against lbn Arabi by the respected scholars of over almost two centuries. Among them Ibn Taymiyyah (1263 – 1328 AD) and his students, but also Ibn Taymiyya’s fiercest opponent al Taqi al Din Al Subki (1284 – 1355 AD), chief judge of Damascus. Also included was Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani. An interesting summary of the pronouncements against Iban Arabi and his followers is provided in the work of the Yemeni scholar al-Husayn lbn al-Ahdal (d. 1451 AD) who cites Ibn al-Dhahabi (1274 – 1348 AD), a student of Ibn Taymiyah:

As for their writings, they are worse than any unbelief. That’s why the just rulers and those who guide on the straight way prevent people from studying them and advise their destruction. They also prohibit people from selling or buying such writings. In the year 738 [1337 AD] the learned men of Egypt reached a consensus, according to which, these [writings] must be banned and their study be prohibited. The qadi Badr al-din al-Maliki says that nowadays Ibn Arabi’s books are not available in either Cairo or Alexandria, and no one dares to produce them in public places. If they are discovered [in somebody’s house] they are confiscated and burned. As for the owner, he is tortured, and if proven to be an adherent [of lbn Arabi], executed. Once, a copy of the Fusus was found in a book market. It was immediately confiscated, tied up with rope, then dragged along the street to the chief qadi, where it was burned for the common good.[32]

Ibn Arabi also claimed to have come into contact with al Khidr. A further identification with the dying-god and the Kabbalistic concept of the Primordial Adam, or Adam Kadmon, and later Metatron, is found in al Khidr’s identification in Sufism with the concept of the Qutb, meaning “pole” or “axis” and with Hermes. The cloak was inherited fifty years later by Ibn Arabi, on his way through Baghdad from Mecca.[33] Ibn Arabi was the Arabic philosopher most responsible for the fusion of Sufism with Neoplatonic thought. One of Ibn Arabi’s most famous works, the Fusus al-Hikam (“Bezels of Wisdom”), was conceived in the course of a “vision” which he experienced near the Kabbah in Mecca. Ibn Arabi claimed that he received the work directly from Muhammad who had appeared to him in Damascus in 1229.

Rose of Baghdad

In the works of Ibn Arabi, Abdul Qadir al Gilani (1077 – 1166 AD) is mentioned as a just man, the Qutb of his time.[34] As he lay on his deathbed, al Gilani reportedly left his Sheikh’s cloak for a man he said would be coming from the west named Muhyiddin, who would be the Qutb of his time. Al Gilani was the founder of the Qadiriyya Sufi order, which is particularly venerated in the Western occult tradition, where it is seen by some as the origin of the Rosicrucian movement. A famous Jewish historian claimed that al Gilani was a secret Jew. Chacham Israel Joseph Benjamin II (1818 – 1864 AD) wrote Eight Years in Asia and Africa from 1846 to 1855, in which he reported that there was a mosque in Baghdad where the grave of al Gilani is highly venerated, and mentioned that, “the Mosque was a Synagogue before,” and that “the Marabut was nothing less than the famous Talmudist Joseph Hagueliti.”[35]

Gilani was a pupil of Ibn Aqil (d. 1119 AD), who had been required by other Hanbalis to denounce his heretical tendencies and retract a work which he had written glorifying al Hallaj, the notorious Sufi who was executed in 922 AD for declaring himself God. However, Hanbali scholar Ibn Qudama (d. 1223 AD), in his Censure of Speculative Theology, doubted the sincerity of his retraction and George Makdisi concurs, suggesting that Ibn Aqil practiced prudent dissimulation (taqiyya). Gilani himself, according to Ibn Rajab, was condemned for harboring heretical works in his school, particularly the writings of the Brethren of Sincerity.[36]

The legend of Gilani’s life and career were largely embellished by his successors. For example, his pedigree was traced on his father’s side in the direct line to Hasan, grandson of the Prophet. But the pedigree was shown to be a fabrication of his grandson the Abu Salih Nasr, to whom numerous fictions can be traced.[37] The list of his performed miracles began at the earliest while only a child, when he was to have begun a fast by refusing the breast of his mother. He was believed to be able to punish distant sinners and assist the oppressed in a miraculous manner, walk on water and move through air. Angels and Jinn, “people of the hidden world” and even the Prophet Muhammed himself, it was said, would appear at his meetings and express their appreciation. According to David Margoliouth, al Gilani’s fame among his followers in some cases nearly displaced that of the Prophet Muhammed, and he is regularly styled the Sultan of the Saints.[38] His reputation attracted numerous pupils from all parts of the Islamic world, and his persuasive rhetoric is said to have converted many Jews and Christians to Islam.

Gilani also spoke of the related notion of the “perfect saint” which became prominent in Sufism. To Gilani, the perfect saint represents a microcosm as his intellect encompasses all, or because his existence comprises all things. This idea of the perfect man among the Sufis is recognized by scholars as dating back to ancient Magian and Gnostic sources, and the notion is traced by Gilles Quispel to Kabbalistic conceptions concerning the primordial Adam.[39] The Epistles of the Brethren of Sincerity define a perfect man as “of East Persian derivation, of Arabic faith, of Iraqi, that is Babylonian, in education, Hebrew in astuteness, a disciple of Christ in conduct, as pious as a Syrian monk, a Greek in natural sciences, an Indian in the interpretation of mysteries and, above all a Sufi or a mystic in his whole spiritual outlook.”[40] The fact that Gilani regarded himself as the perfect saint is suggested in a saying attributed to him: “my foot is on the neck of every saint of God,” thus laying claim to the highest rank and as having obtained the consent of all the saints of the epoch.[41]

Gilani was known as the “Rose of Baghdad.” The rose became the symbol of his order and a rose of green and white cloth with a six-pointed star in the middle is traditionally worn in the cap of Qadiriyya dervishes.[42] The cultivation of geometrical gardens, in which the rose has often held a central place, has a long history in Iran and surrounding countries. In the lyric ghazal, it is the beauty of the rose that provokes the longing song of the nightingale.[43] As the imagery of lover and beloved became a type of the Sufi mystic’s quest for divine love, Ibn Arabi aligns the rose with the beloved’s blushing cheek on the one hand and the divine names and attributes on the other.[44] Two prominent Sufi books are Golestan (“The Rose Garden”) and the Gulshan-i Raz (“The Rose Garden of Secrets”). Written in 1258 CE, the Golestan, one of two major works of the Persian poet Sa’di, considered one of the greatest medieval Persian poets. The Gulshan-i Raz by Shabistari (b. 1288 AD), who became deeply versed in Ibn Arabi, shares many features with Ismaili works, and is considered to be one of the greatest classical Persian works of Sufism.[45] The poems attributed to Rumi’s instructor, Shams Tabrizi (1185 – 1248 AD), by the Ismailis of Badakhshan are published in the Rose Garden of Shams (Gulzar-i Shams) by Mulukshah, a descendant of the Ismaili Pir Shams.[46]

Anthropomorphism

In a Hanbali work on the wearing of the Sufi cloak or mantle (Khirqa), preserved in a unique manuscript in Princeton, by Yusuf ibn Abd al Hadi (d. 909/1503 AD) who was also a Hanbali, Ibn Taymiyyah (1263 – 1328 AD) and his famous pupil Ibn al Qayyim (1292 – 1350 AD) are listed in a Sufi genealogy with well-known Hanbali scholars, all of whom except one, Abdul Qadir al Gilani, were till then unknown as Sufis.[47] Ibn Battuta, the famous traveler and chronicler, reported that while Ibn Taymiyyah was preaching in a mosque he descended one step of the pulpit and said, “God comes down to the sky of this world just as I come down now.” It was because of his tendencies towards anthropomorphic interpretations—denounced as Mujassimah by the Islamic jurists—along with several other rulings considered extreme, that Ibn Taymiyyah spent much of his career in prison, put there by the religious establishment of his time. Though he was widely recognized for the breadth of his knowledge and demonstrations of piety, Ibn Taymiyyah had a tendency for rash exuberance and controversial declarations.

Opinions about Ibn Taymiyyah during his lifetime varied widely. One of his opponents, who had the most success in refuting his views, was Taqi al Din Al Subki who was eventually appointed chief judge of Damascus. Of him Ibn Taymiyyah admitted, “no jurist has refuted me except al Subki.”[48] Al Subki was nevertheless ready to concede to Ibn Taymiyyah’s virtues: “personally, my admiration is even greater for the asceticism, piety, and religiosity with which God has endowed him, for his selfless championship of the truth, his adherence to the path of our forbearers, his pursuit of perfection, the wonder of his example, unrivalled in our time and in times past.”[49] And yet, al Subki remarked, “his learning exceeded his intelligence.”[50]

It was for his typical intemperance that Ibn Battuta declared that Ibn Taymiyyah had a “screw loose.”[51] Among the contemporary scholars who also confronted him, Al Safadi said: “he wasted his time refuting the Christians and the Rafida, or whoever objected to the religion or contradicted it, but if he had devoted himself to explaining al Bukhari or the Noble Quran, he would have placed the garland of his well-ordered speech on the necks of the people of knowledge.”[52] And al Nabahani said: “He refuted the Christians, the Shia, the logicians, then the Asharis and Ahl al Sunna (Sunnis), in short, sparing no one whether Muslim or non-Muslim, Sunni or otherwise.”[53] He was chided by one of his own students, the famous historian and scholar, al Dhahabi, who said, “blessed is he whose fault diverts him from the faults of others! Damned is he whom others divert from his own faults! How long will you look at the motes in the eyes of your brother, forgetting the stumps in your own?”[54] Other former admirers who became critical of him were the Qadi al Zamalkani, Jalal al Din al Qazwini, al-Qunawi, al Jariri.

Umayyad Mosque, a place where Ibn Taimiyya (1263 – 1328) used to give lessons

After three centuries of his views being scrutinized by the leading scholars of the time, like al Subki and others, a Fatwa was finally pronounced by Ibn Hajar al Haytami in the sixteenth century, who declared:

Ibn Taymiyyah is a servant whom God forsook, misguided, blinded, deafened, and debased. That is the declaration of the imams who have exposed the corruption of his positions and the mendacity of his sayings. Whoever wishes to pursue this must read the words of the Mujtahid Imam Abu al Hasan al Subki, of his son Taj al Din Subki, of the Imam al Izz ibn Jama and others of the Shafi, Maliki, and Hanafi scholars... It must be considered that he is a misguided and misguiding innovator and an ignorant who brought evil whom God treated with His justice. May He protect us from the likes of his path, doctrine, and actions.[55]

Tree of Life and the Sephiroth as the body of God

The origin of Ibn Taymiyyah’s anthropomorphism could be attributable to occult sympathies, possibly explained by the fact that he happened to have been born in the city of Harran of the Sabians, which he was forced to flee as a child due to the Mongol conquest in 1268. The Mandaeans, who were related to the Sabians, practiced a well-known anthropomorphic doctrine. The basis of scholars’ conclusion of an affinity between the Kabbalah and the Mandaeans is the existence in both traditions of a body of literature that provides elaborate anthropomorphic descriptions of God. This Kabbalistic tradition is exemplified in the Shiur Komah, a Midrashic text that is part of the literature of Merkabah Mysticism, which records in anthropomorphic terms, the secret names and precise measurements of God’s bodily limbs and parts. Al Kawthari (1879 – 1951 AD), the adjunct to the last Sheikh al-Islam of the Ottoman Empire and a well-known Hanafi jurist, claimed that among the works from which Ibn Taymiyyah derived his anthropomorphic doctrines was the Kitab al-sunna, falsely attributed to Abdallah ibn Ahmad ibn Hanbal, the son of Imam Ibn Hanbal. The work offers blatant allusions to the Cherubim of Merkabah described in the books of Ezekiel and Revelation: “He saw Him on a chair of gold carried by four angels: one in the form of a man, another in the form of a lion, another in that of a bull, and another in that of an eagle, in a green garden, outside of which there was a golden dais.”[56]

Ibn Taymiyyah maintained a secret doctrine, which was more boldly anthropomorphic in nature and which he shared only with his closest initiates. This was discovered by one of his contemporaries, Abu Hayyan al Nahwi, through an acquaintance who had gained Ibn Taymiyyah’s confidence in order to be introduced to his more secret teachings. As al Nahwi recounts in Tafsir al Nahr al Madd (“The Exegesis of the Far-Stretching River”):

I have read in the book of Ahmad ibn Taymiyyah, this individual whom we are the contemporary of, and the book is in his own handwriting, and he has named it Kitab al Arsh [“The book of the Throne of God”], that "God Most High is sitting (Yajlisu) on the Kursi [footstool] but has left a place of it unoccupied, in which to seat the Messenger of God (God bless him and give him peace).” Al Taj Mohammed ibn Ali ibn Abdul Haq Barinbari fooled him [Ibn Taymiyyah] by pretending to be a supporter of his so that he could get it from him, and this is what we read in it.[57]

The Wahhabis in particular, have inherited a vociferous hatred of Sufism from Ibn Taymiyyah, who is widely considered the leading exponent of the kinds of attacks on Sufism that were thought characteristic of the Hanbali school. Sufism had been in conflict with Islamic orthodoxy since the ninth century culminating in the execution of al Hallaj. In the eleventh century, however, a famous Islamic philosopher by the name of al Ghazali proposed a reconciliation of orthodox Islam with Sufism which apparently ended much of the controversy. Nevertheless, there remained bitter debates led primarily by the Hanbalis. However, as George Makdisi has shown, while leading Hanbali scholars showed opposition to certain Sufi practices, a large number of them nevertheless often belonged to Sufi orders. The claim is reinforced by Ibn Rajab (1335 – 1393 AD) in his Dhail, where more than a hundred leading Hanbali scholars are referred to as “Sufis,” accounting for one sixth of the Hanbalis he discussed.[58]

Henri Laoust has written of Ibn Taymiyyah’s affinities with Sufism, and commented that one would search in vain to find in his works the least condemnation of Sufism.[59] Ibn Taymiyyah showed admiration for the works of prominent Sufis like al Junayd, Abdul Qadir al Gilani and Shahab al-Din Abu Hafs Umar al-Suhrawardi (c. 1145 – 1234). Suhrawardi expanded the Sufi order of Suhrawardiyya that was created by his uncle Abu al-Najib al-Suhrawardi (1097 – 1168). The order traced its spiritual genealogy to the son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammed, Ali ibn Abi Talib, through al Junayd Baghdadi and al-Ghazali. It played an important role in the formation of trade-guilds and youth clubs, particularly in Baghdad, where some of its usages, according to occult scholar Idries Shah, resemble those of Freemasonry.[60]

Nevertheless, Ibn Taymiyyah referred to al Gilani as Sheikhuna, “our Sheikh,” a title which he doesn’t proffer on anyone else in all of his works.[61] In his own words, Ibn Taymiyyah confessed in his work al-Masala at-Tabriziya: "I wore the blessed Sufi cloak of Abdul Qadir (al Gilani), there being between him and me two (Sufi Sheikhs)."[62] In a lost work titled Itfa hurqat al-hauba bi-ilbas khirqat at-tauba, by Ibn Nasir ad-Din, Ibn Taymiyyah is quoted as affirming having belonged to more than one Sufi order and praising that of al Gilani as the greatest of all. The Bahdjat al-asrar contains the narrative of many miracles performed by al Gilani, corroborated by chains of witnesses, which Ibn Taymiyyah declared credible, despite the fact that others, namely al Dhahabi, condemned the book as containing frivolous tales.[63]

[1] Janet L. Abu-Lughod. Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), p. 43.

[2] Richard Sorabji. The Philosophy of the Commentators, 200-600 AD: Psychology (with Ethics and Religion). (Cornell University Press, 2005) page 11.

[3] Mikayel Chamchian. History of Armenia (Bishop’s College Press, 1827), p. 110.

[4] Charles Häberl. The Neo-Mandaic Dialect of Khorramshahr (Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2009). p. 18. , p. 1

[5] The Thousand and Twelve Questions, cited from Deutsch, The Gnostic Imagination, (Leiden: E.J Brill, 1995), p. 123.

[6] Deutsch. The Gnostic Imagination, p. 123.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Fakhry. A History of Islamic Philosophy, p. 15.

[9] The Chronology of Ancient Nations, translated and edited by Dr. C. Edward Sachau (London: William H. Allen and Co., 1879.)

[10] David Margoliouth. “Harranians,” Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics.

[11] David Pringree. “The Sabians of Harran and the Classical Tradition.” International Journal of the Classical Tradition, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Summer, 2002), p. 30.

[12] Jean Seznec. The Survival of the Pagan Gods: The Mythological Tradition and its Place in Renaissance Humanism and Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972), p. 52.

[13] Tamara M. Green. The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran (Brill, 1992), p. 171.

[14] Histories. Book III, 44.

[15] Schuchard. Restoring the Temple of Vision, p. 31.

[16] Yves Marquet. La philosophie des Ihwan al-Safa’ (Algiers: Société Nationale d'Édition et de Diffusion, 1975).

[17] “Abdallah ibn Saba.” Encyclopedia Judaica. 1906.

[18] Epistles III: 200, quoted from Fakhry. A History of Islamic Philosophy, p. 190.

[19] Seyyed Hossein Nasr. An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines: Conceptions of Nature and Methods Used for Its Study by the Ikhwān Al-Ṣafāʼ, Al-Bīrūnī, and Ibn Sīnā (SUNY Press, 1993), pp 34–35.

[20] Rasail 21st., p. 166.

[21] The Travels of Marco Polo, XLI.

[22] Chapter 57, Al Hadid: 27.

[23] p. 194.

[24] James W. Morris. “An Arab ‘Machiavelli’?: Rhetoric, Philosophy and Politics in Ibn Khaldun’s Critique of 'Sufism',” (Proceedings of the Harvard Ibn Khaldun Conference (ed.) Roy Mottahedeh (Cambridge, Harvard, 2003).

[25] Islam: An Introduction (State University of Albany: New York Press, 1992), p. 123.

[26] Quran, “Al-Kahf,” 18:66.

[27] David Livingstone. Ordo ab Chao. Volume One, Chapter 3: The Helenistic Age.

[28] Recep Meriç. “Dionysiac and Pyrrhic Roots and Survivals in the Zeybek Dance, Music, Costume and Rituals of Aegean Turkey.” Gephyra, 14 (2017), pp. 215.

[29] E. A. Wallis Budge. The Martyrdom and Miracles of Saint George of Cappadocia (1888), xxxi–xxxiii; 206, 223.

[30] Richard G. Hovannisian & Georges Sabagh. Religion and Culture in Medieval Islam. (Cambridge University Press, 200) pp 109-110.

[31] Abraham Elqayam. Shorter Encyclopedia of Islam.

[32] lbn al-Ahdal. Risala fi sha'n, fol. 30b; cited in Alexander D. Knysh. “Ibn ‘Arabi in the Later Islamic Tradition: The Making of a Polemical Image in Medieval Islam.” (SUNY Press, 1999), p. 127.

[33] Shems Friedlander & Nezih Uzel. The Whirling Dervishes: Being an Account of the Sufi Order known as the Mevlevis and its founder the poet and mystic Mevlana Jalalu'ddin Rumi (SUNY Press, Jan. 1, 1992), p. 39.

[34] Meccan revelations, i. 262; cited in D.S. Margoliouth. “ʿAbd al-Ḳādir.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, First Edition (1913-1936). (Brill Online, 2012). Retrieved from http://www.paulyonline.brill.nl/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-1/abd-al-kadir-SIM_0102

[35] Chacham Israel Joseph Benjamin II. Eight Years in Asia and Africa from 1846 to 1855 (Hanover, Germany, 1861). p. 117.

[36] Ibn Rajab. Dhayl (i. 415-20). Laoust, H. “Ibn al-Dhawzi,” Encyclopedia of Islam. Brill Online, 2012.

[37] Margoliouth, D. S., “ʿAbd al-Ḳādir." Encyclopaedia of Islam, First Edition (1913-1936). Brill Online, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.paulyonline.brill.nl/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-1/abd-al-kadir-SIM_0102

[38] Ibid.

[39] Joel L. Kraemer. Philosophy in the Renaissance of Islam: Abū Sulaymān Al-Sijistānī and His Circle (Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1986), p. 301 n. 85.

[40] Seyyed Hossein Nasr. An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines, p 31–33

[41] Braune, W., “Abd al-Qadir al-jilani.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill Online , 2012. Reference. Retrieved from http://www.paulyonline.brill.nl/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/abd-al-kadir-al-djilani-SIM_0095

[42] Idries Shah. The Sufis (New York: Doubleday, 1964) p. 390.

[43] Layla S. Diba. “Gol o bolbol.” In Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, 11 (London and New York: Routledge 2001), pp. 52–57.

[44] Ibn Arabi. The Tarjuman al-Ashwaq, trans. R. A. Nicholson (Theosophical Publishing House, 1911 and 1978), pp. 130, 145.

[45] Shafique N. Virani. The Ismailis in the Middle Ages (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 148.

[46] Ibid., p. 52.

[47] G Makdisi. “The Hanbali School and Sufism.” Actas IV Congresso de Estudos Arabes e Islamicos (Leiden 1971). p. 122.

[48] Al Safadi. A’yan al ‘Asr, vol. 111, 1196, cited in The Mamluks in Egyptian and Syrian Politics and Society, (ed.) Michael Winter & Amalia Levanoni (Leiden: Brill, 2004), p. 207.

[49] Little. “Did Ibn Taymiyyah Have a Screw Loose.” Studia Islamica xli (1975) p. 100.

[50] Ahmad ibn al-Naqib al-Misri. Reliance of the Traveller: A Classic Manual of Islamic Sacred Law.

[51] Little. “Did Ibn Taymiyyah Have a Screw Loose,” p. 95.

[52] Reproduced by Ibn Rajab in Dhayl Tabaqat al-Hanabila (2:392) and Ibn Hajar in al-Durar al-Kamina (1:159).

[53] Shawahid al Haqq.

[54] al Nasiha al Dhahabiyya li Ibn Taymiyyah, cited in Little. “Did Ibn Taymiyyah Have a Screw Loose,” p. 100.

[55] Fatawa al Hadithiyyah (Maktaba Mishkaat al Islamiyyah), p. 105.

[56] ‘Abd Allah ibn Ahmad Ibn Hanbal. Kitab al-sunna (Cairo: al-Matba`a al-Salafiya, 1349/1930) p. 35.

[57] al-Nahwi. Tafsir al-nahr al-madd, 1.254.

[58] Georges Makdisi. “The Hanbali School and Sufism.” Actas IV Congresso de Estudos Arabes e Islamicos, (Leiden 1971) p. 117.

[59] H. Laoust. Essai sur les idées sociales et politiques d’Ibn Taimîya (Le Caire: Publications de L'Institut Français Archéologie Orientale, 1939), 89 et passim; cited in Georges Makdisi “The Hanbali School and Sufism” Actas IV Congresso de Estudos Arabes e Islamicos (Leiden 1971) p. 121.

[60] Idries Shah. The Sufis, (NY, Doubleday and Co., 1964).

[61] Sh. G. F. Haddad. “Ibn Taymiyyah on ‘Fotooh al-Ghayb’ and Sufism.” Living Islam Retrieved from http://www.abc.se/~m9783/n/itaysf_e.html

[62] G Makdisi. “The Hanbali School and Sufism,” p. 123.

[63] D. S. Margoliouth. “‘Abd al-Ḳādir.”

Volume One

Introduction

Babylon

Ancient Greece

The Hellenistic Age

The Book of Revelation

Gog and Magog

Eastern Mystics

Septimania

Princes' Crusade

The Reconquista

Ashkenazi Hasidim

The Holy Grail

Camelot

Perceval

The Champagne Fairs

Baphomet

The Order of Santiago

War of the Roses

The Age of Discovery

Renaissance & Reformation

Kings of Jerusalem

The Mason Word

The Order of the Dragon