12. The Illuminati

Age of Unreason

In 1797, the Abbé Augustin de Barruel (1741 – 1820), an ex-Jesuit who came to Britain following the September Massacre, published the first volumes of his four-volume account of the French Revolution, Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism. That same year, John Robison (1739 – 1805), professor of natural philosophy at Edinburgh, published his own history of the Revolution, Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the religions and governments of Europe. The two authors shared a conclusion about the source of the events: the Illuminati, a secret society founded by Adam Weishaupt (1748 – 1830), an ex-Jesuit and professor of canon law at the University of Ingolstadt, adopted the Enlightenment ideals of the French philosophes and Encyclopédistes into a secret plan towards the global subversion of church and the state. Once they had infiltrated the French Masonic lodges, with the help of the Duke of Orleans, another descendant of the Rosicrucian “Alchemical Wedding,” and the Comte de Mirabeau, the Illuminati orchestrated the French Revolution under the guise of the Jacobins.

Illuminatus Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel (1744 – 1836), descendant of the Alchemical Wedding

As reported by Terry Melanson, in his history of the order, the Rothschild family had at least three important connections to the Illuminati. They were Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg (1744 – 1817), Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel (1744 – 1836), and the Thurn und Taxis family.[1] Amschel Mayer Bauer, the founder of the Rothschild dynasty, largely achieved his wealth through his association with the ruling family of Hesse-Kassel, direct descendants of Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, from the circle of the first Rosicrucians, a friend of Frederick V of the Palatinate, whose marriage to Elizabeth Stuart formed the basis the Rosicrucian Alchemical Wedding. Maurice’s direct descendant, Frederick II of Hesse-Kassel (1720 – 1785), a knight of the Order of the Garter, was the wealthiest man in Europe, and married Princess Mary of Great Britain, the daughter of King George II of England, who himself was a great-grandson of Frederick V and Elizabeth Stuart. Frederick II’s son, Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, who married Princess Louise of Denmark (1750–1831), the daughter of Frederick V of Denmark (1723 – 1766) and George III’s sister, Princess Louise of Great Britain. The rulers of Denmark belonged to the House of Oldenburg, who like the houses of Branbant and Cleves traced their descent to the Knight Swan. Frederick V’s father, Christian VI of Denmark, had been a member of Zinzendorf’s Order of the Grain of the Mustard Seed.[2]

Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel was a leading member of the Strict Observance, the Bavarian Illuminati and Grand Master of the neo-Rosicrucian order, the Asiatic Brethren, founded by a cousin of Jacob Frank.[3] Prince Charles and the House of Hesse represent the strongest connection yet between the Rothschild Dynasty and the Illuminati. Mayer Amschel Rothschild became a dealer in rare coins and won the patronage of Charles’ brother, the immensely wealthy Crown Prince Wilhelm I of Hesse (1743 – 1821), who had also earlier patronized his father. In 1769, Rothschild became a “Court Agent” of William I, effectively launching the fortunes of that dynasty. On his father’s death in 1785, William I became Wilhelm IX, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, when he inherited the largest private fortune in Europe, derived, with the help of Rothschild, mainly from the hire of Hessian troops to the British government in their fight against the Revolution in the United States.[4]

Genealogy of the Alchemical Wedding

King James I of England + Anne of Denmark

Charles I of England + Henrietta Maria (daughter of Henry VI of France + Marie de Medici)

Charles II of England + Catherine of Braganza (Davidic lineage)

Lady Mary Tudor + Edward Radclyffe, 2nd Earl of Derwentwater

James Radclyffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater

CHARLES RADCLYFFE (founder of the Grand Lodge of England, officer in the Order of the Fleur de Lys, and Grand Master of the PRIORY OF SION)

Mary, Princess of Orange + Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange (1596 – 1632) s. of William the Silent, knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece)

William II, Prince of Orange (1626 – 1650) + Mary II of England (see below)

James II and VII of England, Scotland and Ireland + Anne Hyde

Mary II of England + William II, Prince of Orange (together known as William and Mary)

William III of England, King of England, Ireland, and Scotland

James II and VII of England, Scotland and Ireland + Mary of Modena

James Francis Edward Stuart (1688 – 1766) “The Old Pretender” + Maria Clementina Sobieska (related to Jacob Frank)

CHARLES EDWARD STUART (Bonnie Prince Charlie, "the Young Pretender")

HENRY BENEDICT STUART (Cardinal Duke of York)

ALCHEMICAL WEDDING: Elizabeth Stuart (d. of King James of England) + Frederick IV of the Palatinate (nephew of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange)

Charles Louis, (1617 – 1680) + Landgravine Charlotte of Hesse-Kassel (granddaughter of Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, member of Fruitbearing Society and Rosicrucians)

Charles II (1651 – 1685) + Princess Wilhelmine Ernestine of Denmark

Elizabeth Charlotte, Madame Palatine + PHILIPPE I, DUKE OF ORLEANS (brother of Louis XIV the “Sun King” of France; Order of the Golden Fleece; purported Grand Master of the Order of the Temple)

Élisabeth Charlotte d’Orléans + Leopold, Duke of Lorraine (1679 – 1729)

Francis I (1708 – 1765) + Empress Maria-Theresa (supported Jacob Frank)

Joseph II (had affair with Eva, daughter of Jacob Frank)

Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1674 – 1723, friend of Chevalier Michael Ramsay) + Françoise Marie de Bourbon, Mademoiselle de Blois (d. of Louis XIV + Madame de Montespan (1640 – 1707), close to Philippe I, and involved in Affair of the Poisons and accused of Black Mass)

Louis, Duke of Orléans (1703–1752) + Auguste of Baden-Baden

Louis Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (1725 – 1785) + Louise Henriette de Bourbon

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1747 – 1793, aka Philippe Égalité, Grand Master of the Grand Orient of France, friend of Rabbi Samuel Jacob Falk)

Sophia of Hannover + Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover (1629 – 1698)

Sophia Charlotte (1668–1705) + Frederick I of Prussia (1657 – 1713)

Frederick William I of Prussia (1720 – 1785) + Sophia Dorothea of Hanover

George I of England (1660 – 1727)

Sophia Dorothea of Hanover + Frederick William I of Prussia (s. of Sophia Charlotte + Frederick I of Prussia)

Frederick the Great (1712 – 1786)

Prince Augustus William of Prussia (1722 – 1758)

Frederick William II of Prussia (1744 – 1797, member of Gold and Rosy Cross)

Louisa Ulrika of Prussia + Louisa Ulrika of Prussia (1710 – 1771)

Charles XIII (1748 – 1818, Grand Master of the Swedish Order of Freemasons) + Hedvig Elisabeth Charlotte of Holstein-Gottorp (Hesse-Kassel)

Gustav III (1746 – 1792, patron of Swedenborg and Grand Master of Swedish Rite of Freemasonry) + Sophia Magdalena of Denmark

George II of England (1683 – 1760)

Princess Louise of Great Britain (1724 – 1751 + King Frederick V of Denmark (1723 – 1766)

Sophia Magdalena of Denmark + Gustav III (1746 – 1792)

Christian VII of Denmark (1749 – 1808) + Caroline Matilda of Great Britain (d. of Frederick, Prince of Wales, by Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha)

Frederick VI of Denmark (1768 – 1839)

Princess Louise of Denmark (1750–1831)

Princess Mary of Great Britain (1723 – 1772) + Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (direct descendants of Maurice, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, from the circle of the first Rosicrucians, a friend of Frederick V)

William I, Elector of Hesse (1743 – 1821)

(hired Mayer Amschel Rothschild who founded Rothschild dynasty)Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel (Member of Illuminati and Asiatic Brethren, friend of Comte St. Germain)

Frederick, Prince of Wales (1707 – 1751)

King George III (1738 – 1820) + Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz

Prince Charles was one of three leading figures in eighteenth century secret societies who were descended from the Alchemical Wedding: including Frederick II the Great, King of Prussia, and Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orleans (1747 – 1793), who changed his name to Philippe Égalité during the French Revolution. Tying them all together was Samuel Jacob Falk, the Baal Shem of London, who was linked by some illuminist Masons to Jacob Frank.[5] Through Swedenborg’s legacy and Count Cagliostro’s work, Falk would become revered as the Unknown Superior of revolutionary Freemasonry.[6] From 1764 onward, Falk received the patronage of the wealthy Goldsmid brothers, who also became Masons.[7] Goldsmid is the name of a family of Anglo-Jewish bankers who sprang from Aaron Goldsmid (d. 1782), a Dutch merchant who settled in England about 1763 and was active in the affairs of the Great Synagogue. Two of his sons, Benjamin Goldsmid (c. 1753 – 1808) and Abraham Goldsmid (c. 1756 – 1810), became prominent financiers in the City of London during the French revolutionary wars. Their close familiarity with the sons of George III did much to break down social prejudice against Jews in England and to pave the way for emancipation. Pawnbroking and successful speculation enabled Falk to acquire a comfortable fortune of his own. Falk left large sums of money to charity, and the overseers of the United Synagogue in London still distribute certain payments annually left by him for the poor.[8]

Effectively, after many centuries of subversive opposition to the Catholic Church, the underground secret societies achieved their first political success under the guise of the Illuminati, through their promotion of Enlightenment principles, culminating in the French and American revolutions, and the inception of secularism. The eighteenth-century Age of Enlightenment purportedly represented a late stage of the intellectual evolution of Western civilization, the progress of secularism and scientific rationalism which began in Greece, and progressed through to the Renaissance. The conventional view of the Enlightenment was summarized by Isaiah Berlin, as follows:

The proclamation of the autonomy of reason and the methods of the natural sciences, based on observation as the sole reliable method of knowledge, and the consequent rejection of the authority of revelation, sacred writings and their accepted interpreters, tradition, prescription, and every form of non-rational and transcendent source of knowledge…[9]

Unbeknownst to the average person, while its proponents denounced scripture as “superstition,” the Enlightenment was a project of occult secret societies. The name Enlightenment betrays the influence of the Illuminati and other Illuminés lodges who, by way of Jacob Boehme, advanced the Kabbalah of Isaac Luria. As according Isaac Luria, human intellectual progress is the evolution of God coming to know himself, so history is the evolution of secularism, where man uses his own “reason” to arrive at the conclusion that man is God, and therefore, the author of his own destiny. Their secularism was not founded on a rejection of God, but as a Gnostic interpretation of divinity, where the true God is Lucifer, who seeks to teach man “liberty” from the supposedly oppressive commandments of the creator God of the Bible.

Therefore a radical reorganization of society was thought, not only possible, but necessary. As modern propagandist William H. McNeill described:

History came to be viewed, in Gibbon’s phrase, as a record of the miseries, crimes and follies of mankind, but in that record there appeared a slow, halting but unmistakable progress. Reason, to optimistic eyes, seemed to be winning new victories every day; a new age of enlightenment had dawned and mankind seemed on the point of emerging from a long night of superstition and ignorance. All that remained was to eliminate the remnants of bygone times: in particular, to men like Voltaire, that meant the destruction of the Church. Once all such obstacles had been removed, nothing would any longer prevent a rational reorganization of society and the inception of an age of general happiness when the natural goodness of men would prevail.[10]

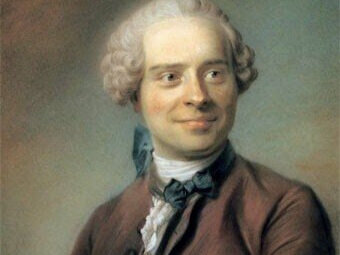

Voltaire (1694 – 1778)

The Illuminati lent their name to the epoch which they ultimately influenced, the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, fulfilling the Frankist agenda referred to by Gershom Scholem as the “Religious Myth of Nihilism.”[11] Ultimately, Frank taught his followers that the overthrow and destruction of society was the only thing that could save mankind. Despite the fact that they were all outwardly religious, the Frankists sought “the annihilation of every religion and positive system of belief,” and they dreamed “of a general revolution that would sweep away the past in a single stroke so that the world might be rebuilt.”[12] As indicated by Charles Novak, in Jacob Frank, Le Faux Messie (Jacob Frank, the False Messiah) according to the Talmud, as the messianic age would be preceded by chaos, perversion and the destruction of Edom, a Jewish equivalent for Rome, or Europe. Therefore, in order to hasten the advent of the Messiah, it would be necessary to sow the seeds of such chaos.[13] Of the revolutionary philosophy of the Frankists, Gershom Scholem wrote, in Kabbalah and Its Symbolism: “For Frank, anarchic destruction represented all the Luciferian radiance, all the positive tones and overtones, of the word Life.”[14]

The Enlightenment emerged out of Renaissance humanism and was also preceded by the Scientific Revolution and the work of Francis Bacon. Some date the beginning of the Enlightenment to René Descartes’ 1637 philosophy of Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I Am”). Others regard the publication of Newton’s Principia Mathematica in 1687 as the culmination of the Scientific Revolution and the beginning of the Enlightenment.[15] Some of the major figures of the Enlightenment included Denis Diderot, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Leibniz, Locke, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Adam Smith, Baruch Spinoza, and Voltaire. Nearly all of the primary figures of the French Enlightenment, namely Voltaire, Mirabeau, Montesqieu, Diderot, D’Alembert, Condorcet, and Rousseau, were all members of Freemasonry or the Illuminati. Denis Diderot (1713 – 1784), one of the most important leaders of the movement, gathered scores of the philosophes to compile the great achievement of the Enlightenment, the Encyclopedie. Those philosophes most closely associated with the Encyclopedie developed a view of the world that was materialist, deterministic, and even atheistic. The Encyclopedie is considered one of the forerunners of the French Revolution.

Paris became the center of a philosophical movement challenging traditional doctrines and religions led by Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778), who argued for a society based upon reason as in ancient Greece, rather than faith and Catholic doctrine, for a new civil order based on natural law, and for science based on experiment and observation. The famous Swiss philosopher Rousseau, who exercised an immense influence on the French Revolution, was a Mason.[16] Moreover, several lodges were named in honor of Rousseau and his ideals. In The Social Contract, Rousseau put forward the democratic theory of sovereignty, in which he argued that the social contract is not established between the ruler and the ruled, but among the ruled themselves. If a government failed to satisfy the people, they would have the right the change it in any way they pleased. Moreover, Rousseau advocated the opinion that, insofar as they lead people to virtue, all religions are equally worthy, and that people should therefore conform to the religion in which they have been brought up. During the period of the French Revolution, Rousseau was the most popular of the philosophers among members of the Jacobin Club.

Frederick the Great and Voltaire also offered and gave support to Rousseau.[17] When the Swiss authorities condemned both Rousseau’s Emile and The Social Contract, Voltaire issued an invitation to Rousseau to come and reside with him, commenting that: “I shall always love the author of the ‘Vicaire savoyard’ whatever he has done, and whatever he may do… Let him come here [to Ferney]! He must come! I shall receive him with open arms. He shall be master here more than I. I shall treat him like my own son.”[18] In July 1762, after Rousseau was informed that he could not continue to reside in Bern, Jean le Rond d’Alembert (1717 – 1783) advised him to move to the Principality of Neuchâtel, ruled by Frederick. As the Seven Years' War was about to end, Rousseau wrote to Frederick, thanking him for the help and urging him to put an end to military conflicts and to endeavor instead to keep his subjects happy.[19]

Voltaire was initiated into Freemasonry a little over a month before his death. On April 4, 1778, Voltaire attended the Loge des Neuf Sœurs in Paris, and became an Entered Also associated with the same lodge was Benjamin Franklin, a major figure in the American Enlightenment, who associated with Count Zinzendorf and defended the cause of the Moravians.[20] Apprentice Freemason. According to some sources, “Benjamin Franklin… urged Voltaire to become a freemason; and Voltaire agreed, perhaps only to please Franklin.”[21] Voltaire is famous for the expression écrasez l'infâme (“crush the infamous”) which inspired the Revolution. The phrase refers to abuses of the people by royalty and the clergy that Voltaire saw around him, and the “superstition” and intolerance that the clergy bred within the people.[22]

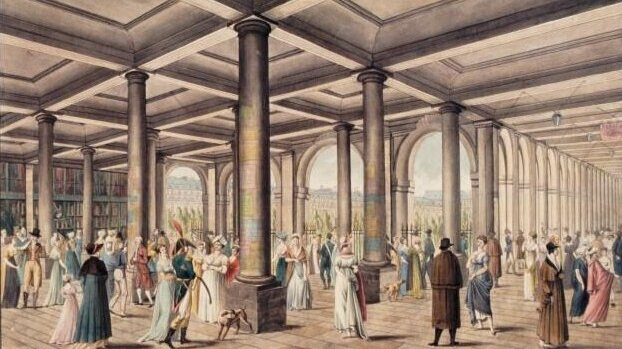

Palais-Royal

Palais-Royal in Paris of the Duke of Orleans

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1747 – 1793), descendants of the Alchemical Wedding, great-grandson of Philippe, Duke of Orleans, the purported Grand Master of Baron Hund’s the Templar Order, and friend of the Sabbatean Samuel Jacob Falk, the Baal Shem of London.

In winter 1776-77, Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orleans, who would go on to play a leading role in the French Revolution as Philippe Égalié, traveled to London where he sought out Falk, who consecrated a talismanic ring that would ensure the Duke’s accession to the French throne.[23] The Duke of Orleans was great-grandson of Chevalier Ramsay’s friend, Philippe II, Duke of Orleans. As Joscelyn Godwin explained, “The whole Orleans family, ever since Philippe’s great-grandfather the Regent, was notoriously involved in the black arts.”[24] The Duke of Orleans, who was Frederick the Great’s lieutenant, was Grand Master of the Grand Orient, the chief body of Freemasonry in France, was instituted by French Masons in 1772. The Duke of Orleans was a cousin of King Louis XVI and one of the wealthiest men in France. The duke’s base of operations was the Palais-Royal in Paris. Originally called the Palais-Cardinal, the palace was the personal residence of Cardinal Richelieu, after whose death in 1642 became the property of the King and acquired the new name Palais-Royal. After Louis XIII, the son of Marie de Medici, died the following year, it became the home of the Queen Mother Anne of Austria and her young sons Louis XIV and Philippe I, Duke d’Orléans, along with her advisor Cardinal Mazarin. From 1649, the palace was the residence of the exiled Henrietta Maria—wife and daughter of the deposed Charles I of England and Marie de Medici—and her daughter Henrietta Anne Stuart, where they were sheltered by Henrietta Maria’s nephew, Louis XIV.

After Henrietta Anne was married to Philippe I, Duke d’Orléans, the palace became the main residence of the House of Orléans. After Henrietta Anne died in 1670, the Philippe I married Elizabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate, the daughter of Charles Louis I of the Palatinate, who was the son of the Rosicrucian “Alchemical Wedding” of Frederick V of the Palatinate and Elizabeth Stuart. Elizabeth Charlotte was therefore the cousin of King George I of England. Philippe I’s eldest son was the heir to the House of Orléans, Philippe II, the purported Grand Master of Baron Hund’s the Templar Order and a friend of Chevalier Andrew Michael Ramsay. Philippe II married Françoise Marie de Bourbon, daughter of Louis XIV and his mistress Madame de Montespan, who was accused of practicing Black Masses are part of the Affaire des poisons. Their son, Louis, Duke of Orléans (1703 – 1752) was brought up by his mother and his grandmother, Elizabeth Charlotte. The Palais-Royal was soon the scene of the notorious debaucheries of Louise Henriette de Bourbon, who married the Duke of Orléans’s son, Louis Philippe (1725 – 1785), in 1743. Louise Henriette was the daughter of Louis Armand II, Prince of Conti, and of Louise Élisabeth de Bourbon, whose father, Louis, Prince of Condé (1668 – 1710), was the grandson of Louis, Grand Condé, who was involved in a conspiracy with Menasseh ben Israel, Isaac La Peyrere and Queen Christina.[25] Louis’ mother, Princess Anne of the Palatinate, was the daughter of Charles Louis I’s brother, Edward, Count Palatine of Simmern and Anna Gonzaga. Louise Élisabeth’s brother was Louis, Count of Clermont, Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of France. Louis Philippe, like his father, was a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. His son by Louise Henriette was Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orleans, later known as Philippe Égalité. Upon inheriting the title of Duke of Orleans in 1785, Philippe also became the Premier Prince du Sang, the most important personage of the French kingdom after the king’s immediate family.

Order of Heredom

Emmanuel Swedenborg

In the early days of the Rite of Seven Degrees, to which belonged Falk and Swedenborg, the French artist and engraver Lambert de Lintot, one of the leaders of the Royal Order of Heredom, cited the Duke of Orleans as his Deputy Grand Master.[26] The Royal Order of Heredom maintained links with the Count of Clermont (1709 – 1771), Grand Master of the Grand Orient, and his elite Rose-Croix rite, the Rite of Perfection.[27] It is often mistakenly reported that Ramsay mentioned the Templars in his oration. Nevertheless, perceptive listeners would have understood the mention of the “Crusader knights” to be an indirect reference to the Templars, the memory of whom was still controversial in France. Therefore, when Ramsay sent a copy to Cardinal Fleury (1653 – 1743), chief minister of France, asking for a Church blessing of the principles of Freemasonry, the obvious allusion to the heretical Templars led Cardinal Fleury to reply with an interdiction of all Masonic reunions, and may have led to the Pope’s indictment of the organization a year later.[28]

The paternity into highly Christianized degrees within a special order of Freemasonry, the Royal Order of Heredom of Kilwinning, which claimed Bonnie Prince Charlie as its Grand Master, is generally attributed to Ramsay.[29] While British Freemasonry traced its origin to the operative guilds of masons, the Écossais Masons of France, from 1737 onwards, placed the origin of the Order in crusading chivalry. It was amongst these Freemasons that the upper degrees known as the Scottish Rite arose. This degree known in modern Masonry as “Prince of the Rose-Croix of Heredom or Knight of the Pelican and Eagle” became the eighteenth and the most important degree in what was later called the Scottish Rite. According to the tradition of the Royal Order of Scotland this degree had been contained in it since the fourteenth century, when the degrees of H.R.M. (Heredom) and R.S.Y.C.S. (Rosy Cross) are said to have been instituted by Robert Bruce in collaboration with the Templars after the battle of Bannockburn.[30]

In answer to a question about the ritual term “Heredom,” Charles R. Rainsford (1728 – 1809), a British MP, Swedenborgian Freemason and a close friend of Falk, replied that it did not refer to an actual mountain in Scotland but rather to the Jewish symbol for Mons Domini or Malchuth, the tenth Sephira of the Kabbalah:

The word “Heridon” [sic] is famous in several degrees of masonry, that is to say, in some invented degrees (grades forges), or in degrees of masonry socalled. Apparently, the enlightened brethren who have judged it proper to make the law, that Jews should be admitted to the Society have received the word with the secrets (mysteres) which have been entrusted to them.[31]

In 1741, Swedenborg and his Masonic colleagues in London assimilated the sexual practices of the Sabbateans into highly Christianized degrees within the Order of Heredom.[32] Marsha Keith Schuchard asserts that Swedenborg also pursued an active career as a Jacobite spy on behalf of the Swedish government, that he was a Freemason and used secret Masonic networks to relay intelligence back to Sweden and to undertake other secret missions. As Schuchard explained, the Kabbalistic belief that proper performance of Kabbalistic sex rites rebuilds the Temple and manifests the Shekhinah between the conjoined cherubim was particularly attractive to the initiates of the Order. One of the leaders of this rite, the French artist and engraver Lambert de Lintot, produced a series of hieroglyphic designs, which included phallic and vaginal symbolism, representing the regeneration the psyche and the rebuilding the Temple of the New Jerusalem.[33]

It was through a Moravian friend that Swendenborg apparently met Falk, and over the next decades, their mystical careers would be closely intertwined.[34] Although denounced as a scoundrel and a charlatan by his fellow Jews, Falk was revered as a master of the Kabbalah by Sabbateans and Christian occultists and Masons, who sought his learning and assistance in medicine, alchemy, sexual magic, treasure-finding, lottery-predictions, and political intrigue. Reports of his exploits circulated in courts and lodges from London to Holland, France, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, and Algiers. The main lines of communication for these reports were the secret networks of Écossais Masonic lodges of the exiled Jacobites. Thus, explains Schuchard, “Dr. Falk’s appearance on the Écossais stage was a new but not unprecedented act in the long-running drama of the ‘Judeo-Scots’.”[35] In 1744–45, Swedenborg’s political party—the pro-French “Hats”—secretly cooperated with the Stuarts and exploited Ecossais lodges for secret communications and arms shipments. At The Hague, the Swedish ambassador Joachim Preis, a close friend of Swedenborg, worked with Simon and Tobias Boas, Jewish bankers and active Masons, who became his patrons and protectors. The Boas brothers often assisted Swedish diplomats in political and financial affairs.[36]

From the activities recorded by Falk’s servant Hirsch Kalisch in his diary of 1747-51, evidence emerges in the journals, correspondence, and diplomatic reports of visitors to London which suggests, explains Schuchard, “that Falk became involved in a clandestine Masonic system that utilized Kabbalah and alchemy to support efforts to restore James Stuart, the ‘Old Pretender,’ to the British throne.”[37] From the first published report of his kabbalistic skills, the Count of Rantzow’s Memoires (1741), reported that Falk also performed a magical ceremony with a black goat before the Duke of Richelieu (1696 – 1788), French ambassador in Vienna, and the Count of Westerloh, during which Westerloh’s valet had his head turned backward and died of a broken neck.[38] Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu, was the Marshals of France and the lover of Marie Louise Élisabeth d’Orléans, Duchess of Berry, the eldest of the surviving children of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans.

Swedish Rite

Grand Masters of the Swedish Rite: King Gustav III (1746 – 1792) of Sweden and his brothers, Prince Frederick Adolf and Prince Charles, later Charles XIII of Sweden (1748 – 1818).

As noted by Robert Freke Gould in History of Freemasonry Throughout the World, Swedenborg’s writings were widely asserted to have had a powerful in shaping the doctrines of the Swedish Rite.[39] The Swedish Rite was first developed in the beginning of the eighteenth century from exiled Jacobites in France. In the Swedish Rite, the St. Andrew’s Degrees are referred to as the Scottish Degrees, probably coming from the Jacobites. According to Scottish Rite historian Albert G. Mackey, the Swedish Rite “is a mixture of the pure Rite of York, the high degrees of the French, the Templarism of the former Strict Observance, and the system of Rosicrucianism.”[40] The first high-degree “Scottish” lodge was started in 1756 with Carl Friedrich Eckleff (1723 – 1786), whose father had worked closely with Swedenborg, as Master. In 1759, Eckleff started the Chapitre Illuminé “L’Innocente,” which utilized the seven-degree system of the Royal Order of Heredom and the Clermont Rite.[41]

In 1774, Duke Charles of Södermanland, later Charles XIII of Sweden (1748 – 1818), nephew of Frederick the Great and Eckleff's successor, became Grand Master of both systems whereby all Masonry in Sweden came under the Grand Lodge. Duke Charles reformed Eckleff’s system and in 1801 launched the Swedish Rite with eleven degrees, which is largely the same system used today.[42] When the Swedish Rite was reorganized in 1766, it consisted of nine Degrees: the first three grades were the Craft grades of Freemasonry, followed by fourth, Scots Apprentices and Fellows; fifth, Scots Masters; sixth, Knights of the East and Jerusalem; seventh, Knights of the West, Templars; eighth, Knights of the South, Master of the Temple; and ninth, Vicarius Salomonis. In the eighth degree the legend of the Order of the Temple is communicated: the new Grand Master Beaujeu, after he had been imparted with the secrets of the Templar treasure, with the assistance of nine Templars, disinterred the corpse of de Molay and, disguising themselves as Masons, they cleaned the remains in their aprons. Afterwards, they adopted the apron as a badge of their new order and sought refuge amongst the fraternity of stone‑masons.[43]

The Swedish lodges claimed to possess precious documents that contained the Masonic secrets embedded in “the hieroglyphic language of the old Jewish wisdom books,” a reference to De Lintot’s engravings and Falk’s revelations.[44] Some of these documents were obtained by Swedenborg from Jewish and French Masons in London.[45] Recently published documents revealed that the Duke Charles and his brothers performed Kabbalistic-Swedenborgian rituals in the royal palace, in a secret Masonic “Sanctuary,” modelled on the Temple of Jerusalem.[46]

Duke Charles’s brother, Gustav III of Sweden (1746 – 1792), Swedenborg’s patron, married Sophia Magdalena of Denmark, whose sister was the wife of Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel. After his seizure of the Swedish throne through a coup d’état in 1772, Gustav III made Freemasonry an instrument of state and expanded the Swedish Rite into foreign countries, particularly in hostile Russia and Prussia, where initiates loyal to the Swedish Grand Master would form a pro-Swedish fifth column.[47] He supported the nationalist rebellion led by Czartorisky, which was crushed by Russia and Prussia. In 1772, Czartorisky visited Tobias Boas at The Hague to solicit his support, and then both men traveled to London to seek the help of Falk’s sorcery.[48] Moving on to Paris, Czartorisky called on the Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1747 – 1793), later known as Philippe Égalité, Grand Master of the Grand Orient system of French Masonry, and probably informed him about Falk.[49] In 1783, during a visit to the aging Bonnie Prince Charlie in Italy, Gustav III was named the Pretender’s successor as Grand Master of the Order of the Temple.[50]

Illuminés of Avignon

Masonic initiation

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin (1743 – 1803).

Eckleff introduced new Templar rituals which involved a descent into a series of caves under the crypt of Jacques de Molay.[51] As explained by G.A. Schiffmann, in Die Entstehung der Rittergrade in der Freimaurerei um die Mitte des XVIII. Jahrhunderts (1882), the de Molay legend came from Sweden to Germany in three avenues. First, it was contained in the Eckleff Documents, brought back from Sweden in 1766. In the second, it is found in the rituals which the deputies of Duke Charles handed over in 1777to the deputy of Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick (1721 – 1792), the Grand Master of the Strict Observance. The third was printed in the appendix, was sent in 1783 by Duke Charles to Prince Christian of Hesse (1776 – 1814), the son of Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel. Prince Charles’ wife’s sister, Sophia Magdalena of Denmark, married Gustav III of Sweden. According to Schiffmann, Duke Charles’ version would have been based on that of Eckleff, from whom he had purchased sold all his Masonic papers and writings.[52]

Eckleff based his system on certain documents from around 1750 that had been received from abroad, which repeated the legend of Guillaume Beaujeu, who supposedly received the Templar treasure from de Molay and succeeded him as Grand Master of the order. Known as the “Eckleff Documents,” they were written in cipher in French and signed by “Frédéric Asscher, Secrétaire” in the name of a foreign Grand Chapter, Grand Chapitrede la Confraternité l'llluminée. According to the words of Duke Charles it was a chapter in Geneva that had received its knowledge from another in Avignon, where there is the mystical high-degree system of the Illuminés.[53]

The Martinists, or French Illuminés, were a movement evidently more powerful and influential than the more infamous Illuminati. From 1740 onwards there existed at Avignon, capital of the department Vaucluse, a school or rather many schools of Hermeticism, working in some cases under Masonic forms on the basis of the Craft Degrees, with an intermediate structure of so-called Scots Degrees. The head of the movement was apparently Dom Antony Joseph de Pernety (1716 – 1796), a Benedictine monk, alchemist and mystic.[54] In 1760, Pernety founded his sect of Illuminés d’Avignon in that city, declaring himself a high initiate of Freemasonry and teaching the doctrines of Swedenborg and William Postel and practicing alchemy.[55] To escape the Inquisition in Avignon, Pernety had to go into exile in Berlin where Frederick II of Prussia appointed him curator of his library. He was therefore able to continue his research on the Great Work and embarked on the study of old grimoires to discover the secret of the Philosopher’s Stone. He developed a passion for the mystical doctrines of the Swedenborg and he founded, with the Polish count Grabienka, the Illuminés of Berlin.[56]

Later on, Grabienka added Martinist and Swedenborgian philosophy.[57] Martinism was founded by Martinez Pasquales, a Rose-Croix Mason who also showed an interest in Swedenborg, and founded the Ordre des Chevalier Maçons Elus-Coën de L’Univers (Order of the Knight Masons, Elected Priests of the Universe) in 1754. Pasquales knew Kabbalah, and legend has it that he travelled to China to learn secret traditions.[58] Gershom Scholem has called attention to the contacts between the Ordre de Elus-Coën and the Sabbateans.[59] Pasquales had frequently been described as a Jew. A Martinist named Baron de Gleichen (1733 – 1807) wrote that, “Pasqualis was originally Spanish, perhaps of the Jewish race, since his disciples inherited from him a large number of Jewish manuscripts.”[60]

Jean-Baptiste Willermoz (1730 – 1824)

Martinism involved theurgical procedure, referring to the practice of rituals sometimes seen as magical in nature, performed with the purpose of invoking the action or evoking the presence of one or more “gods.” According to J. M. Roberts, the Elus-Coën philosophy “was expressed in a series of rituals whose purpose was to make it possible for spiritual beings to take physical shape and convey messages from the other world.”[61] Martinism was later propagated in different forms by Pasquales’ two students, Louis Claude de Saint-Martin and Jean-Baptiste Willermoz (1730 – 1824), who was a member of the Rite of the Philalethes, which was formed out of Swedenborgian, Martinist, and Rosicrucian mysteries.

Pasqually first established his rite at Marseilles, Toulouse, and Bordeaux, then in Paris, and before long Martiniste lodges spread all over France with the center at Lyons under the direction of Willermoz.[62] In the 1770s, Willermoz came into contact with Baron von Hund and the German Order of the Order of Strict Observance which he joined in 1773 with the chivalric name Eques ab Eremo and Chancellor of the Chapter of Lyons. His brother Pierre-Jacques Willermoz, doctor and chemist, contributed to the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D’Alembert. Willermoz was the formulator of the Rectified Scottish Rite, or Chevaliers Bienfaisants de la Cité-Sainte (CBCS), founded in 1778 as a variant of the Rite of Strict Observance, including some items coming from the Elus-Coën of his teacher Pasquales. The order oversaw numerous lodges, including the Strict Observance and the Lodge Theodore of Good Counsel in Munich. Like the Strict Observance, the Rectified Scottish Rite also repeated a story similar to the one found in the reported in the Deuxième Section, de la Maçonnerie parmi les Chrétiens:

Three of our ancestors, possessing the great secret, found a way to escape the general and particular searches that were made against them. They wandered in the woods and mountains, from kingdom to kingdom; finally they withdrew to caves near Heredom in Scotland where they lived, served and rescued by the Knights of St. Andrew of the Thistle, the ancient friends and allies of the Templars. These three Templars made a new alliance with the Knights of St. Andrew and transmitted to these wise men the tradition that I have just apprised you of and their secret, which had been possessed by the former Knights of St. Andrew, during the Crusades.[63]

In 1773, a new link between Falk’s and Swedenborg’s theosophy was initiated by the Marquis de Thome, who established a Swedenborgian Masonic lodge in Paris and subsequently studied Kabbalah under Falk.[64] In 1767, the French physician Benedict Chastanier established a lodge of Illuminés Théosophes in London, affiliated with the Illuminés of Avignon, whose rituals also drew on Swedenborgian symbolism. The Marquis de Thomé, who had met Swedenborg in Paris in 1769, began to assist his frère J. P. Moët in translating Swedenborg’s works into French, and he established a special Swedenborgian rite in Paris by 1773. Three years later, Chastanier determined to establish a Masonic society that would publish and disseminate Swedenborg’s writings. In 1776, joining with other Masons who shared his devotion, Chastanier formed the “London Universal Society for the Promotion of the New Jerusalem Church,” which included Falk’s close friend, General Charles Rainsford.[65]

Chastanier and Thomé joined forces with the Rite of the Philalethes which investigated the theosophical claims of Falk, Swedenborg, and other gurus of illuminism.[66] The Philaléthes could be traced back to 1771 and an amalgamation of all the Masonic groups that had been effected at the new lodge of the Amis Réunis.[67] The society was founded by Savalette de Langes (1745 – 1797), State Treasurer of France under Louis XVI, was Grand Officer of the Grand Orient, under the Duke of Orleans as its Grand Master. Before supporting the ideas of the French Revolution, de Langes was captain of the national guards of the battalion of Saint-Roch and aide-de-camp of the marquis de La Fayette (1757 – 1834). Like Savalette, many members of the Amis Réunis came from France’s financial establishment, as well as high-ranking officials who had direct access to the king and his ministers, in addition to bankers, businessmen, landowners and the highest level of finance officials from the military.

The Rite of the Philalethes, into which were joined the higher initiates of the Amis Réunis, was formed by de Langes in 1773. The members of this rite—which some historian qualify as an “occult academy”—imposed the rule of rejecting nothing and taking an interest in mystical societies on the fringes of Masonry to understand the relations of “Man with spirits” and take the name of “Philalèthes.”[68] The Philalethes accumulated a vast library and archive serving to synthesize the “Masonic science” and provided the Amis Réunis with an alchemical lab. They were dedicated to uncovering the “rapport of masonry with Theosophy, Alchemy, the Cabala, Divine Magic, Emblems, Hieroglyphs, the Religious Ceremonies and Rites of different Institutions, or Associations, masonic or otherwise.”[69] They were particularly interested in the Bohemian Brethren of Comenius, which evolved into the Moravian Church of Zinzendorf.[70] Their ultimate aim was a “total synthesis of all learning,” towards the creation of a “world religion that all the devout of whatever persuasion can embrace.”[71] A modified form of this rite was instituted at Narbonne in 1780 under the name of Free and Accepted Masons du Rit Primitif, founded by the Marquis de Chefdebien d’Armisson, a member of the Stricte Observance as well as the Grand Orient and of the Amis Réunis.

Illuminati

Illuminati initiation ritual

In 1771, according to Barruel and Lecouteulx de Canteleu, a certain Jutland merchant named Kölmer, who had spent many years in Egypt, returned to Europe in search of converts to a secret doctrine founded on Manicheism that he had learned in the East. Lecouteulx de Canteleu suggests that Kölmer was Altotas, described by Figuier as “this universal genius, almost divine, of whom Cagliostro has spoken to us with so much respect and admiration.” On his way to France, Kölmer stopped at Malta, where he met the famous charlatan Count Cagliostro (1743 – 1795), another important disciple of Jacob Falk, but he was driven away from the island by the Knights of Malta after he nearly brought about an insurrection amongst the people. Kölmer then travelled to Avignon and Lyons, where he made a few disciples amongst the Illuminés. In the same year, Kölmer went on to Germany, where he encountered Adam Weishaupt (1748 – 1830) and initiated him into all the mysteries of his secret doctrine.[72]

Rousseau was an important influence on the subversive aspirations of Weishaupt, founder of the notorious Bavarian Illuminati. As a young boy, Weishaupt was educated by the Jesuits. He later enrolled at the University of Ingolstadt where he studied the ancient pagan religions and was familiar with the Eleusinian mysteries and the mystical theories of Pythagoras. As a student, he had drafted the constitution for a secret society modeled on the ancient mystery schools.[73] Weishaupt first made contact with a Masonic lodge in either Hanover or Munich in 1774, but he was sadly disappointed by what he considered their ignorance of the occult significance of Freemasonry and its pagan symbolism or origins.[74] On May 1, 1776, the year of the American Revolution, Weishaupt, announced the foundation of the Order of Perfectibilists, which was later to become more widely known as the Illuminati, taking the Owl of Minerva as its symbol.

Weishaupt was referred to as “a Jesuit in disguise” by his closest associate, Adolph Freiherr Knigge (1752 – 1796).[75] Pope Clement XIV dissolved the Jesuits in 1773, but three years later Weishaupt announced the foundation of the Order of Perfectibilists, known as the Illuminati, taking the Owl of Minerva as its symbol. John Robison, who in 1798 exposed the evolution of the Illuminati in Proofs of a Conspiracy, remarked of German Freemasonry, “I saw it much connected with many occurrences and schisms in the Christian church; I saw that the Jesuits had several times interfered in it; and that most of the exceptionable innovations and dissentions had arisen about the time that the order of Loyola was suppressed; so that it should seem, that these intriguing brethren had attempted to maintain their influence by the help of Free Masonry.”[76]

Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1745 – 1804), friend of Adam Weishaupt, member of the Illuminati and great-grandfather of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819 – 1861), the husband of Queen Victoria.

In his own words, Weishaupt boasted, “Oh! Men, of what cannot you be persuaded?”[77] Weishaupt, who founded the Illuminati with the aim of subverting the world’s religions, was able to coerce his dupes to conform unwittingly to his project by following a system of indoctrination by degrees, and feigning to offer enlightened interpretations of Christianity on humanitarian political principles. Its members pledged obedience to their superiors and were divided into three main classes: the first included “novices,” “minervals,” and “lesser illuminati.” The second consisted of freemasons: “ordinary,” “Scottish,” and “Scottish knights.” The third or “mystery” class comprised two grades of “priest” and “regent” as well as “magus” and “king.”[78]

An initiate was led into a room where, in front of an empty throne, there stood a table on which were placed the traditional symbols of kingship: a scepter, a sword, and a crown. The initiate was invited to pick up the objects but was warned that if he did so he would be refused entry to the order. The initiate was then taken into a second room draped in black, where a curtain was pulled to reveal an altar covered in a black cloth on which stood a cross and a red Phrygian cap of the Mysteries of Mithras. This cap was handed to the initiate with the words “Wear this—it means more than the crown of kings.”[79]

The Owl of Minerva perched on a book was an emblem used by the Bavarian Illuminati in their "Minerval" degree.

Weishaupt had decided to infiltrate the Freemasons to acquire material to expand his own ritual and establish a power base towards his long-term plan for political change in Europe. In early in February 1777, he was admitted to the Rite of Strict Observance. Weishaupt was persuaded by one of his early recruits, his former pupil Xavier von Zwack, that his own order should enter into friendly relations with Freemasonry, and obtain the dispensation to set up their own lodge. A warrant was obtained from the Grand Lodge of Prussia called the Royal York for Friendship, and the new lodge was called Theodore of the Good Counsel, which was quickly filled with Illuminati. By establishing Masonic relations with the Union lodge in Frankfurt, which was affiliated to the Premier Grand Lodge of England, lodge Theodore became independently recognized, and able to declare its independence. The lodge Theodore was named with the intention of flattering Charles Theodore, Elector of Bavaria (1724 – 1799). Charles Theodore succeeded his father as Count Palatine of Sulzbach in 1733 and inherited the Electoral Palatinate and the duchies of Jülich and Berg in 1742, with the death of Charles III Philip (1661 – 1742), Elector Palatine. As a new mother lodge, lodge Theodore could now spawn lodges of its own.

The recruiting efforts amongst the Frankfurt Masons resulted in the allegiance of Knigge, who appeared to believe in the “Most Serene Superiors” which Weishaupt claimed to serve, though Weishaupt withheld the secrets of the higher degrees. In 1781, when Knigge protested, Weishaupt finally confessed that his superiors and the supposed antiquity of the order were fictions, and the higher degrees had yet to be written.[80] Knigge targeted the leaders of the Masonic lodges, the masters and the wardens, and was often successful in placing the entire lodge at the disposal of the Illuminati.

In letters to Weishaupt, Baron de Bassus (1742 – 1815), a great recruiter for the order, boasted of having initiated “the President, the Vice-President, the principal Counsellors of Government, and the Grand Master of the Posts” The “Master of the Posts” referred to the Princely House of von Thurn und Taxis, a family of German nobility that was a key player in the postal services in Europe during the sixteenth century, and until the end of the Holy Roman Empire, and one of the wealthiest families in the world. There were two members of the family who had joined the Illuminati: Count Maximilian Carl Heinrich Joseph von Thurn und Taxis (1745 – 1825) and Count Thaddäus von Thurn und Taxis (1746 – 1799). De Bassus wrote to Weishaupt that Thaddäus, along with the Governor of Tyrol, Count Johann Gottfried von Heister, Vice President of the Provincial Government in Innsbruck, Count Leopold Franz von Kinigl and other influential counselors of the government, were “inflamed by our system.”[81]

Karl Anselm of Thurn and Taxis (1733 – 1805), member of the Order of the Golden Fleece, employed Amschel Rothschild as his preferred banker

Weishaupt had advised his disciples to “… seek to gain the masters and secretaries of the Postoffices, in order to facilitate our correspondence.”[82] Likewise, in 1780, Amschel Rothschild also sought similar privileges when he became one of the preferred bankers of Karl Anselm of Thurn and Taxis (1733 – 1805), Head of the Princely House of Thurn and Taxis, Postmaster General of the Imperial Reichspost, and member of the Order of the Golden Fleece. As explained by Amos Elon in Founder: A Portrait of the First Rothschild and His Time:

The Thurn and Taxis postal service covered most of central Europe and its efficacy was proverbial… Rothschild’s ties with the administration of the Thurn and Taxis postal service were profitable to him in more than one way. He was a firm believer in the importance of good information. The postal service was an important source of commercial and political news. The Prince was widely thought to be paying for his monopoly as imperial postmaster by supplying the Emperor with political intelligence gained from mail that passed through his hands. He was not averse to using this intelligence himself—perhaps in conjunction with Rothschild—to make a commercial profit.[83]

Membership in the Illuminati then expanded widely. Within a short period of time, the Illuminati had lodges all over Germany and Austria, and branches of the order were also founded in Italy, Hungary, France, and Switzerland. The importance of the order lay in its successful recruitment of the professional classes, churchmen, academics, doctors and lawyers, and its more recent acquisition of powerful benefactors. Karl August, Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg with his brother and later successor August, Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg governor of Erfurt, Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick, his chief assistant in Masonic matters, Johann Friedrich von Schwarz, and Count Metternich of Koblenz were all enrolled. Ernest II and Karl August were the great-great-grandsons of John VI, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst, (1621 – 1667) whose father, Rudolph, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst (1576 – 1621), was the brother of Christian of Anhalt, the chief advisor of Frederick V of the Palatinate, and architect of the political agenda behind the Rosicrucian movement. Christian’s brother was Augustus, Prince of Anhalt-Plötzkau, who headed Rosicrucian court that included the millenarian Paul Nagel, a collaborator of Baltazar Walther, whose trips to the Middle East inspired the legend of Christian Rosenkreutz and was the source of the Lurianic Kabbalah of Jacob Boehme. John VI’s sister was Dorothea of Anhalt-Zerbst, who married Augustus the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, a member of the Fruitbearing Society along with his friend of Johann Valentin Andreae, the reputed author of the Rosicrucian manifestos, and who had Rabbi Templo’s Hebrew treatise on the Temple translated into Latin, and to have Leon’s portrait engraved.[84]

As identified by Terry Melanson in Perfectibilists, a number of leading members of the Knights of Malta also shared membership in the Illuminati. It is claimed that Baron Maximilian von Branca (1765 – 1835), a priest of the ecclesiastical court in Munich, and also the Grand Commander of the Knights of Malta in Bavaria, was a member of the Illuminati.[85] Illuminati member Baron Jean-Baptiste de Flachslanden (1749 – 1822), who was invested as the Bailli of Aquila in the Knights of Malta, was proposed as Grand Master of the Order, but the decision was vetoed by First Consul Bonaparte.[86] Illuminati member Baron Johann Kasimir von Häffelin (1737 – 1827) was also the commander and vicar-general of the Bavarian branch of the Knights of Malta.[87]

Comte St. Germain

Comte de St. Germain (c. 1691 or 1712 – 1784)

Count Cagliostro was a disciple of the most notorious figure of the era, the enigmatic Comte de St. Germain.[88] Saint-Germain may even have met Falk, through their mutual friend Dr. De la Cour, a wealthy Jewish doctor, who often brought Christians curious to meet Falk.[89] St. Germain was believed to have alchemical powers that allowed him to transmute lead into gold, as well as many other magical powers such as the ability to teleport, levitate, walk through walls, influence people telepathically, and even to have been immortal. St. Germain’s true identity has never been established, but speculations at the time tended to agree that he was of Jewish ancestry.

St. German was apparently educated by Gian Gastone de Medici (1671 – 1737), Grand Duke of Tuscany. Gian’s mother, Marguerite Louise d’Orléans, was descended from the House of Orleans and the House of Lorraine, who trace their descent back to René of Anjou. Her father was Gaston, Duke of Orléans, the son of Henry IV of France Marie de Medici. Gaston’s brother was Louis XIII of France, whose son was Louis XIV, the “Sun King,” who married Madame de Montespan, and whose brother was Philippe I, Duke of Orleans. Gaston’s sister was Christine of France, who built the Palazzo Madama according advice of alchemists, and who was married to Victor Amadeus I, Duke of Savoy, grandson of Emmanuel Philibert and Margaret of Valois who consulted Nostradamus for the birth of their son Charles Emmanuel I. Gian’s father was Cosimo III de' Medici (1642 – 1723), Grand Duke of Tuscany, the grandson of Cosimo II de Medici who was a sponsor of Galileo. Gian, whose reign was marked by the reversal of his father’s conservative policies, abolished taxes for the poor, penal laws restricting Jews and ended public executions.

St. Germain claimed to be the son of Francis II Rakoczi (1676 – 1735), the Prince of Transylvania, who was the grandson of George II Rakoczi (1621 – 1660) and Sophia Bathory, two families who employed the emblem of the Order of the Dragon.[90] In 1639, Samuel Hartlib published a pamphlet dedicated to George II, who at the time was the hope of the scattered Protestants of south-eastern Europe, now that Bohemia had been reconquered and the Swedes had drawn back to the Baltic coast.[91] Today considered a national hero, Francis II Rakoczi was a leader of the Hungarian uprising against the Habsburgs in 1703-11 as the prince of the Estates Confederated for Liberty of the Kingdom of Hungary. Francis II was also Prince of Transylvania, an Imperial Prince, and knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Francis II Rakoczi was the lover of Princess Elżbieta Sieniawska, the grandmother of Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski (1677 – 1766), who along with Marius Lubomirsky, both leaders of Ecossais Freemasonry in Warsaw and avid students of Kabbalah, supported Bonnie Prince Charlie.[92] Both princes had contacts with Sabbatian Jews, and Czartorisky was criticized as “a half-Sabbatian.”[93] Czartorisky was also in contact with Falk.[94] Czartorisky married Izabela Fleming, who in Paris in 1772 met Benjamin Franklin, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire. Czartorisky is one of the figures immortalized in Jan Matejko’s 1891 painting, Constitution of May 3, 1791. Prince Lubomirsky would later marry a Sabbatian and convert to Judaism.[95] When Jacob Frank’s followers converted to Christianity, the Czartoriskys and their Masonic allies welcomed them to the “new” Poland, and there would be a growing exchange between the Frankists and Masonic Kabbalists.[96]

St. Germain was the supposed Grand Master of Freemasonry and had become an acquaintance of Louis XV King of France and his mistress Madame de Pompadour. In 1743, he lived for several years in London, writing music, and he became a close friend of the Prince of Wales, the eldest but estranged son of King George II and Sophia of Hanover, daughter of Frederick V and Elizabeth Stuart. He was forced to flee the city, though, after becoming involved in a Jacobite plot to restore the Stuarts and being exposed as a spy for the French. He negotiated on behalf of the French king with Frederick the Great during the Seven Years’ War and was responsible for the alliance between France and Prussia. He was also involved in the plot to overthrow Peter the Great in 1762 and replace him with Catherine the Great. In gratitude, she allegedly placed the Masonic lodges in Russia under her personal protection.[97]

Egyptian Freemasonry

Illustration of a Cagliostro performance in Dresden

Cagliostro claimed to have been admitted to the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, or Knights of Malta, among whom he studied alchemy, Kabbalah and magic. Cagliostro was born Giuseppe Balsamo to a poor family in Albergheria, which was once the old Jewish Quarter of Palermo, Sicily. Illuminatus Goethe, in his non-fiction Italian Journey, claimed that Cagliostro was Jewish. However, Cagliostro later stated during a trial to have been born of Christians of noble birth but abandoned as an orphan upon the island of Malta. He claimed to have travelled as a child to Medina, Mecca, and Cairo. Upon return to Malta, where he was received by Manuel Pinto da Fonseca, the 68th Prince and Grand Master of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta from 1741 until his death, who shared an interest in alchemy.[98]

In early 1768, Cagliostro left for Rome where he found a job as a secretary to Cardinal Orsini. He married a seventeen-year-old girl named noblewoman, Lorenza Felicioni, whom it was alleged he controlled using hypnotism, which had learned from his fellow Mason, Anton Mesmer (1734 – 1815).[99] The theme became the basis of a 1949 film titled Black Magic, based on Alexandre Dumas’ novel Joseph Balsamo, and starring Orson Welles. Cagliostro befriended a fraudster named Marquis Agliata, from whom he learned the skills of a forger in exchange for sexual favors from his young wife.[100] The couple also set out together on the pilgrimage route that ran through Italy, France, and Spain to the shrine of Saint James of Compostela in Galicia, during which they met Casanova. Cagliostro then travelled to London, where it is said he befriended the Comte St. Germain.

In London, Cagliostro also befriended Rabbi Falk, and may also have met with Swedenborg, whom he referred to in personal terms.[101] Though it was said that Cagliostro had been initiated into the rite by the Comte St. Germain, Schuchard presented evidence that it was Falk who sent Cagliostro on the mission of Egyptian Freemasonry.[102] Cagliostro’s Egyptian Rite was a very complex system of oracles, quasi-Egyptian rituals and ceremonial magic. Although the masonic rite was divided into men’s and women’s lodges. However, as noted by psychical researcher Paul Tabori, in his Secret and Forbidden, the main degree initiation ceremony in the “ladies lodges” were openly orgiastic. According to Tabori:

After passing through several tests, novices assembled at dawn in the ‘temple.’ A curtain rose and the spectators gazed at a man seated on a golden globe, completely nude, holding a snake in his hand.

The naked figure was Cagliostro himself. The ‘high priestess’ explained to the amazed ladies that both truth and wisdom were naked and that they (the ladies) must follow their example. Thereupon the beauties stripped and Cagliostro delivered a speech in which he declared that sensual pleasure was the highest aim of human life. The snake which he held gave a whistle, whereupon thirty-six ‘genii’ entered, clad in white gauze. ‘You are’ Cagliostro said, ‘chosen to fulfill my teachings!’ This was the sign for the beginning of the orgies.”[103]

Cagliostro and Falk visited a Masonic lodge at The Hague in 1777, where they launched a campaign to recruit Swedenborgian and Ecossais Masons in many countries to their Egyptian Rite. In the schismatic “Antiquity” lodge, established by the Scottish Mason and former Jacobite, William Preston. When Falk visited the lodge, he listed himself as a member of the lodge “Observance of Heredom, Scotland.”[104] Falk was alleged to have been connected to the medieval sect of Assassins, and when Cagliostro travelled to Écossais and Swedenborgian lodges in Germany and Lithuania, he was welcomed as the emissary of the “Great Cophta,” whose identity as Falk was revealed only to higher initiates.[105]

According to a Report of the Vatican Inquisition (1791), “Cagliostro perceived that their [Freemasons’] ceremonies were disfigured and disgraced by magic and superstition; the principles of Swedenborg, a Swedish preacher; and those of M. Falk, a Jew rabbi, are regarded as chiefs by the illuminated.”[106] Cagliostro’s Masonic patron, Frederick Rodolphe Saltzmann, reported, “[Cagliostro] says a lot of good about Swedenborg and complains that he has been persecuted. In vain the Swedes now want to resuscitate his ashes, they will discover nothing. The greatest man in Europe is the famous Falk in London.”[107] According to Catherine the Great (1729 – 1796), “Cagliostro came at just the right moment for himself, when several lodges of Freemasons, who were infatuated with Swedenborg’s principles, were anxious at all costs to see spirits; they therefore ran to Cagliostro, who declared he had all the secrets of Dr. Falk.”[108]

In 1777 Cagliostro and Lorenza left London after which they travelled through various German states, visiting lodges of the Rite of Strict Observance looking for converts to Egyptian Freemasonry. In September 1780, after failing in Saint Petersburg to win the patronage of Catherine the Great, the couple made their way to Strasbourg in France. In 1784, they travelled to Lyon, where they founded the co-Masonic mother lodge La Sagesse Triomphante of his rite of Egyptian Freemasonry. In 1785, Cagliostro and his wife went to Paris in response to an invitation of Cardinal de Rohan (1734 – 1803), whose friendship facilitated their introduction at the Court of the French King Louis XVI, from which circles a number of dignitaries were initiated into his Egyptian Freemasonry, the Supreme Council of which was established in Paris in 1785. According to Cardinal de Rohan, “the magnetic séances of [Franz Anton] Mesmer are not to be compared with the magic of my friend the Count de Cagliostro. He is a genuine Rosicrucian, who holds communion with the elemental spirits. He is able to pierce the veil of the future by his necromantic power.”[109]

Congress of Wilhelmsbad

Wilhelmsbad in 1783

Rabbi Samuel Jacob Falk (1708 – 1782), the Baal Shem of London

It is reputed that the ground plan for the French Revolution was discussed at the Grand Masonic Convention in 1782 at Wilhelmsbad, at which Mirabeau attended as an observer.[110] At this time, both French and German Freemasons were very unclear with regard to the whole subject, purpose and conflicting accounts of the origins of Masonry. This confusion led to the Convent of Wilhelmsbad on July 16, 1782, and attended by representatives of masonic bodies from all over the world. Through the influence of Swedenborg and his pupil Cagliostro, Falk had become revered as the Unknown Superior of revolutionary Freemasonry, and the convention was determined to learn more about him. As Savalette de Langes, royal treasurer in Paris, reported in his correspondence with the Marquis de Chefdebien:

Dr. Falc, in England. This Dr. Falc is known to many Germans. From every point of view he is a most extraordinary man. Some believe him to be Chief of All the Jews, and attribute all that is marvelous and strange in his conduct and in his life to schemes which are entirely political… There has been a curious story about him in connection with Prince de Guemene and the Chev. de Luxembourg relating to Louis XV. whose death he had foretold. He is practically inaccessible. In all the higher Sects of Adepts in the Occult Science, he passes as a man of higher attainments…[111]

Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick (1721 – 1792)

The congress was convoked by Wilhelm I of Hesse-Kassel, while his brother, Illuminatus Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, one of the founders of the Rite of Philalethes was main organizer.[112] Prince Charles, who was preoccupied with a search for the “hidden superiors” and the “true secret,” was also an ardent devotee of alchemy, possessing his own laboratory, and was being a student of Comte St. Germain, whom he had hosted at his home.[113] Prince Charles was also associated with an extensive affiliation of lodges and diverse societies, referred to as l’École du Nord (“School of the North”), in northern Germany and Denmark. Followers of Louis Claude de Saint-Martin and Martines de Pasqually and Swedenborg, they claimed to have achieved physical manifestations of the active cause and intelligence. Having succeeded in summoning apparitions of Saint John, and thus awaited his imminent return or second coming. They also professed belief in the teachings of Pythagoras and the doctrine of metempsychosis, or the transmigration of souls.[114] Prince Charles’ devotion to Swedenborg is affirmed by Schuchard: “Through the medium of Swedenborgianism and Sabbatian Kabbalism, the rival systems of Sweden and Denmark reached an accommodation in the 1780s. Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel corresponded with the Swedenborgian Exegetic Society in Stockholm and with the Theosophical Society in London.”[115] The Theosophical Society was the publishing arm of the secret Universal Society, founded by Benedict Chastanier.[116]

The main purpose of the convention was to decide the fate of the Strict Observance. The Order of the Strict Observance was in reality a purely German association composed of men drawn entirely from the intellectual and aristocratic classes, and, in imitation of the chivalric orders of the past, known to each other under knightly titles. Thus, Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel became Eques a Leone Resurgente, Illuminati member Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick was Eques a Victoria, the Prussian minister Johann Rudolph von Bischoffswerder (1741 – 1803) Eques a Grypho, Baron de Wächter Eques a Ceraso, Joachim Christoph Bode (1731 – 1793), Councillor of Legation in Saxe-Gotha, Eques a Lilio Convallium, Christian Graf von Haugwitz (1752 – 1832), Cabinet Minister of Frederick the Great Eques a Monte Sancto.

The sister of Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, was married to Frederick the Great, who taught Ferdinand in the strategy of war, making him a colonel, going on to become known as one of the most successful generals of the eighteenth century. Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick, was initiated in 1740 into the Lodge of The Three Globes in Berlin. His father was Ferdinand Albert II, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1680 – 1735), whose father was a member of the Fruitbearing Society. Ferdinand’s mother was Princess Antoinette of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, the great-granddaughter of Augustus the Younger, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg. Princess Antoinette was also an aunt to Empress Maria Theresa, a protector of Jacob Frank, and whose son Joseph was reputed to have had an affair with Frank’s daughter Eve. Princess Antoinette sister, Charlotte Christine of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel married Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich of Russia, the son and heir of Peter the Great, who initiated by Sir Christopher Wren and introduced Freemasonry in his dominions. Ferdinand’s other sister, Juliana Maria of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, married Frederick V of Denmark. In 1760, King George II also conferred Ferdinand with the Order of the Garter.

Ferdinand, who was declared General Grand Master of the assembled lodges, set forth the agenda for the congress. The questions Ferdinand proposed be posed at Wilhelmsbad to the Grand Master of the Strict Observance were:

(1) Is the origin of the Order an ancient society?

(2) Are there really Unknown Superiors, and if so, who are they?

(3) What is the true aim of the Order?

(4) Is this aim the restoration of the Order of Templars? (5) In what way should the ceremonial and rites be organized so as to be as perfect as possible? (6) Should the Order occupy itself with secret sciences?[117]

The Rectified Scottish Rite was codified at Wilhelmsbad under the presidency of Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick who became Grand Master of the order. The designated French-speaking secretary is Jean-Baptiste Willermoz. Among the final conclusions of the congress was that the legend of Templar origins was rejected, to become “symbolic” and “spiritual” within the Rectified Scottish Rite:

After several curious researches on the history of the Order of the Templars, from which is derived that of the Masons, which have been produced, examined and compared in our lectures, we have convinced ourselves that they present only traditions and probabilities without an authentic title, which could merit all our confidence, and that we were not sufficiently authorized to call ourselves the true and legitimate successors of the Templars, that moreover prudence dictated that we leave a name which would make one suspect the project of wanting to restore an order proscribed by the concurrence of two powers, and that we abandon a form that would no longer fit the mores and the needs of the century.[118]

As Mirabeau observed, “this same Grand Master and all his assistants had worked for more than twenty years with incredible ardour at a thing of which they knew neither the real object nor the origin.”[119] Ostensibly a discussion of the future of the order, the 35 delegates knew that the Strict Observance in its current form was doomed, and that the Convent of Wilhelmsbad would be a struggle over the pieces between the German mystics, under Duke Ferdinand and their host Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, and the Martinists, under Jean-Baptiste Willermoz. The lack of a coherent alternative to the two strains of mysticism allowed the Illuminati to present themselves as a credible option. The Convent of Wilhelmsbad actually achieved was the demise of the Strict Observance. They renounced the Templar origins of their ritual, while retaining the Templar titles and administrative structure. Charles of Hesse-Kassel and Ferdinand Duke of Brunswick remained at the head of the order, but in practice the lodges were almost independent. The Germans also adopted the name of the Willermoz’s Chevaliers bienfaisants de la Cité sainte, and some Martinist mysticism was imported into the first three degrees, which were now the only essential degrees of Freemasonry.[120]

Johann Joachim Christoph Bode (1731 – 1793)

Opposed to the Martinists was Bode. Bode was a friend of the German philosopher Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 – 1781), who together in 1767 created the J.J.C. Bode & Co. publishing firm and store in Hamburg.[121] This store sold its own and other works, including Lessing’s Dramaturgie, Goethe’s Götz. Bode was Member and Past Master of Lodge Absalem at Hamburg, and served as deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Hamburg. In 1782, he adopted a radical interpretation of the Enlightenment and broke with the Christian mysticism of Willermoz. At Wilhelmsbad, Bode immediately entered negotiations with Knigge, and finally joined the Illuminati in January 1783, acquiring the rank of Major Illumitatus. Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel joined the following month.[122]

Several Masonic conventions attempted to unify Freemasonry in Germany and to establish collaboration in occult studies. A further congress was convened in Paris in 1785 by the Amis Réunis and the Philalethes. Bode and the Baron von Busche were present, as well Marquis de Chefdebien and Marquis de Condorcet (1743 – 1794). The congress brought together 120 deputies, most of whom were notorious occultists.[123] Among the topics discussed were the linkage between Jacob Falk and Jacob Frank.[124] Ferdinand Duke of Brunswick led the German delegation and the English one was led by a close friend of Falk, General Charles R. Rainsford (1728 – 1809), a British MP, Swedenborgian Freemason and a member of the Royal Society. Rainsford left hundreds of texts in five languages dealing with alchemy, Kabbalah, magic, medicine, and astrology. Rainsford’s forty volumes of unpublished papers in the British Museum form the major source material for the study of English Freemasonry and occultism in the late eighteenth century. In 1761, he received a company and served under Ferdinand of Brunswick in Germany, with whom he became friends. In 1783, one year after Falk’s death, Rainsford, who had been collaborating with Falk on a highly secretive Kabbalistic-Masonic scheme, received inquiries from Parisian Masons about Falk’s system. In 1785, Rainsford served under the Duke of Cumberland in Flanders, who served as Grand Master from 1782-1790. Cumberland opposed his brother King George III of England on his American policy and personally inspired Lafayette’s defense of the American colonies, urging him to go to America in 1776.[125]

Savalette de Langes had planned to undermine the work of the Wilhelmsbad convent. The summons to the congress was sent to 228 brothers and was accompanied by a questionnaire. In ten points, it offered an in-depth analysis of the foundations of Masonry and its current operations, causing many defections of representative of the lodge such as: Saint-Martin, the Lavater brothers, Ferdinand de Brunswick or even Joseph de Maistre. It opens with a hundred delegates from lodges alongside twenty-eight Philalethes and closed on May 26 after thirty sessions. The concluding report qualified the effort of the convention as insufficient, but it also revealed the desire to create a new association of Philalethes with a European dimension.[126]

Philadelphes

Finally, in July 1785, an evangelist preacher and Illuminatus named Lanze had been sent as an emissary of the Illuminati to Silesia, but was struck down by lightning. The instructions of the Order were found on him. The diabolical nature of the Illuminati was revealed to the Government of Bavaria, and the Order was officially suppressed. Ex-Jesuit Ignaz Franck (1725 – 1795) was the first to publicly condemn the Illuminati. Franck was the confessor for the Elector of Bavaria, Duke Charles Theodore, and had exerted exceeding influence on the sovereign since 1765, when Franck was appointed the tutor of Charles Theodore’s daughter.[127] Although the Illuminati had infiltrated the Lodge Theodore of Good Counsel, which was named after him, on June 22, 1784, Charles Theodore issued an edict against societies secret or otherwise not authorized by the sovereign. In March 2, 1785, Charles Theodore issued the second Edict in 1785 against secret societies, specifically naming the Illuminati and Freemasonry. Finally, when in July 1785, Lanze struck down by lightning and the instructions of the Order were discovered, Charles Theodore “was furious” and issued a third edict on August 16, 1787, requiring “all members of the order to repent and register with the government within eight days, on pain of severe punishment.”[128]

The interrogations of members were conducted by Franck and censor Johann Caspar von Lippert to conduct the purges against suspected Illuminati. In accordance with Jesuit tradition, Franck “shunned the trappings of power in order to operate all the more effectively from behind the scenes,” explained Klaus Epstein in The Genesis of German Conservatism.[129] Charles Theodore appointed Franck to “head the much-feared Specialcommission in gelben Zimmer des Schlosses which investigated the Illuminati, encouraged informers, and decided upon exemplary punishments.”[130]

During the printing and publishing of the original documents of the Illuminati in 1787, Charles Theodore made sure copies were sent to various governments in Greater Germany and beyond. However, the Bavarian government simply did not have the power to enforce anything beyond its borders. On November 15, 1790, the Charles Theodore issued his final public denunciation of the Illuminati, and a fourth verdict:

The Elector has learned, partly by the spontaneous confession of some members, partly by sound intelligence, that despite the several Edicts of 1784 and 1785 (and in the same month in 1787), the Illuminati still hold, albeit in smaller numbers, secret meetings throughout the Electorate, but especially in Munich and the surrounding area; they continue to attract young men to the cause and have maintained a correspondence with [secret] societies and with members in other countries. They continue to attack the state and especially religion, either verbally or through pamphlets.[131]

Weishaupt fled and documents and internal correspondence, seized in 1786 and 1787, were subsequently published by the government in 1787. In 1787, following the disbanding of the Illuminati, Weishaupt was granted asylum in Gotha by Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1745 – 1804), great-grandfather of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, who became a member of the Illuminati.[132] Ernest II had been a member of the Strict Observance and served as Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Germany. He was initiated into the Illuminati in 1783, was appointed the inspector of upper-Saxony, and Coadjutor to the National Superior, Stolberg-Rossla in 1784, and National Director of Germany, after helping Weishaupt. Ernest II continued to support Weishaupt and resisted all attempt on the part of Charles Theodore to have him arrested.

The Illuminati nevertheless proceeded with their plot. Suspicion remained that its members might still be working in secret, spreading subversive ideas, and conspiring behind the scenes. Prior to the French Revolution, Weishaupt himself is to have said, “Salvation does not lie where strong thrones are defended by swords, where the smoke of censers ascends to heaven or where thousands of strong men pace the rich fields of harvest. The revolution which is about to break will be sterile if it is not complete.”[133]