15. Haskalah

Out of the Ghetto

According to Isaac Mayer Wise (1819 – 1900), a Scottish Rite Freemason and a leading exponent of the Jewish Reform movement, “Masonry is a Jewish institution whose history, degrees, charges, passwords, and explanations are Jewish from the beginning to the end.”[1] Five of the “The Eleven Gentlemen of Charleston” who were founders of the Mother Supreme Council of Scottish Rite Freemasonry at Charleston—Isaac Da Costa, Israel DeLieben, Abraham Alexander Sr., Emanuel De La Motta and Moses Clava Levy—were congregants of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, the colony’s first synagogue, founded in 1749, and one of the oldest Jewish congregations in the United States.[2] Beth Eolhim was founded by Isaac Da Costa and Moses Cohen, both members of Mikveh Israel and also the Sublime Lodge of Perfection in Philadelphia.[3] The congregation played a significant role in bringing Reform Judaism to the United States, a tradition which Rabbi Marvin Antelman has linked to the Sabbatean Movement.

The Jewish Reform movement, that began in Hamburg, Germany, and was associated with the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite in Charleston, North Carolina, was inspired by the activities of Samuel Jacobson (1768 – 1828), who confessed to have been influenced by Moses Mendelssohn (1729 – 1786), and his friend Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 – 1781). In was in the correspondence of Mendelssohn that was found the certificate held in the Schiff Collection at the New York Public Library, preserved by his friend, the notorious Illuminati publisher Friedrich Nicolai, and mentioned briefly by Jewish historian Jacob Katz in Out of the Ghetto, includes a list of ordination that ranks Mendelssohn after Rabbi Eybeschütz among the successors of Shabbetai Zevi.[4] Mendelssohn’s teacher David Fränkel (c. 1704 – 1762) was a student of Rabbi Michael Chasid, the chief rabbi of Berlin and a Sabbatean.[5] In 1761, Mendelssohn met in Hamburg with Jonathan Eibeschutz, who wrote an essay extolling Mendelssohn, which appeared in 1838, in a publication called Kerem Chemed.[6]

As a proponent of the thought of Spinoza, Mendelssohn was the father of the Jewish Enlightenment, or Haskalah. Spinoza’s rejection of Judaism in particular, and religion in general, laid the groundwork for the advent of the Haskalah, a movement supporting the adoption of Enlightenment values, and promoted an expansion of Jewish rights within European society, which transformed Jews into a race, and Judaism into a nationality, setting the stage for the advent of Zionism.[7] Effectively, the Sabbateans invented the term “Orthodox Judaism,” to suggest that their heretical interpretations were just an evolution of the true faith, while rejecting the traditions it was founded upon, which were the Torah and the Talmud, in favor of the antinomianism of the Kabbalah. As Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch commented in 1854:

It was not the “Orthodox” Jews who introduced the word “orthodoxy” into Jewish discussion. It was the modern “progressive” Jews who first applied this name to “old,” “backward” Jews as a derogatory term. This name was at first resented by “old” Jews. And rightly so. “Orthodox” Judaism does not know any varieties of Judaism. It conceives Judaism as one and indivisible. It does not know a Mosaic, prophetic and rabbinic Judaism, nor Orthodox and Liberal Judaism. It only knows Judaism and non-Judaism. It does not know Orthodox and Liberal Jews. It does indeed know conscientious and indifferent Jews, good Jews, bad Jews or baptised Jews; all, nevertheless, Jews with a mission which they cannot cast off. They are only distinguished accordingly as they fulfil or reject their mission.[8]

Moses Mendelssohn (1729 – 1786), successor of Shabbatai Zevi

In Spinoza’s Critique of Religion, Leo Strauss suggested that “modern Judaism is a synthesis between rabbinical Judaism and Spinoza.”[9] For his rejection of revelation in favor of reason, Spinoza is recognized as one of the early and seminal figures of the Enlightenment.[10] In Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity 1650-1750, Jonathan Israel, Professor in the School of Historical Studies, credits Spinoza as the originator of the core principles of modern thought. In his main political work, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1677), Spinoza opposed superstition, argues for tolerance and the subordination of religion to the state, and pronounces in favor of liberal democracy. According to Spinoza:

But its ultimate purpose is not to dominate or control people by fear or subject them to the authority of another. On the contrary, its aim is to free everyone from fear, so that they may live in security, so far as possible. That is that they may retain to the highest possible degree their natural right to live and to act without harm to themselves or to others. It is not, I contend, the purpose of the state to turn people from rational beings into beasts or automata, but rather to allow their minds and bodies to develop in their own ways, in security, and enjoy the free use of reason, and not to participate in conflicts based on hatred, anger, or deceit, or in malicious disputes with each other. Therefore, the true purpose of the state is in fact freedom.[11]

One of the tendencies that characterized Haskalah was anti-messianism, implying that Jews could change their present situation by taking political action instead of waiting passively for the messiah. The belief developed from the perceived failure of the mission of Sabbetai Zevi. The crypto-Sabbatean maskil Jonathan Eybeschütz claimed that the main achievement of the messiah would be that the Jews “would find clemency among the nations,” reflected as improved legal and social status in Europe.[12] Before their emancipation, most Jews were isolated in residential areas from the rest of the society. The followers of the Haskalah, known as maskilim, advocated “coming out of the ghetto,” not just physically but also mentally and spiritually, calling for an assimilation into European society. One of the biggest changes of the Haskalah was in education. Orthodox Jews were opposed to the Haskalah because it went against traditional Judaism and the role of Talmud in education. The Haskalah marked the end of the use of Yiddish, the revival of Hebrew and an adoption of European languages. Mendelssohn wrote a Hebrew commentary on the Bible called the Biur to accompany a German translation.

The spread of the ideals of the Enlightenment in Europe throughout the eighteenth century brought about a profound change in the attitude of the educated class toward the Jews.[13] The two important events that contributed to the emancipation of the Jews was the 1782 Edict of Tolerance when Joseph II extended religious freedom to the Jewish population, and the Emancipation Edict of 1812, issued by Frederick William III, a knight of the Order of the Garter and the Order of the Golden Fleece, whose father, Frederick William II, was the nephew of Frederick II the Great, a member of the Berlin Illuminati and knight of the Golden and Rosy Cross.[14] Joseph II was also a Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Fleece. His mother, Empress Maria Theresa, supported the cause of Jacob Frank, and Joseph II himself was reputed to have had an affair with Frank’s daughter Eva. His brother and uncle were Grand Masters of the Teutonic Knights and listed as purported Grand Masters of the Priory of Sion.

Emperor Joseph II (1741 – 1790), son of Empress Maria Theresa, both supporters of Jacob Frank

Illuminatus and Sabbatean Joseph von Sonnenfels (1732 – 1817)

The architect of the principles which guided the “benevolent despotism” of Emperor Joseph II was crypto-Sabbatean and Illuminatus, Joseph von Sonnenfels, who along with along with Ignaz Edler von Born was a leader of the Illuminati lodge, the famous Masonic Lodge Zur wahren Eintracht, attended by Mozart.[15] Sonnenfels drafted the Patent of Toleration, enacted in 1781, which granted religious freedom to Lutherans, Calvinists, and Serbian Orthodox, but it was not until the 1782 Edict of Tolerance when Joseph II extended religious freedom to the Jewish population.[16] Joseph II decreed that Jews must establish secular schools or allowed to attend general secondary schools and universities. Nevertheless, Joseph II remained of the belief that Jews possessed “repellent characteristics.”[17] Sonnenfels invited Mendelssohn to embrace Christianity, but when he was rebuked by Mendelssohn’s Jerusalem in 1783, he apologized in 1784 by making Mendelssohn a member of his German Scientific Society and the Vienna Academy of Sciences.[18] Due to his position within the government, Sonnenfels was appointed rector of the University of Vienna and in 1810 as head of the Academy of Sciences.

Adam Mickiewicz (1798 – 1855), regarded as the greatest poet in all Polish literature, who was also a secret Frankist as well as a Martinist

The first laws granting emancipation to Jews in France were enacted during the French Revolution, establishing them as equal French citizens. In countries conquered during the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon emancipated the Jews and introduced other ideas of freedom from the French Revolution. As explained by the historian Jacob Katz:

It is astonishing how many Jews who experienced emancipation from the ghetto almost instinctively described the event in terms drawn from the vocabulary of traditional Jewish messianism. Such emancipating rulers as Napoleon and the Emperor Joseph II of Austria were compared explicitly with the biblical Cyrus, and the dawning of the Enlightenment was frequently portrayed as the equivalent of the messianic age.[19]

The Sabbateans’ veneration of Napoleon, which survived beyond his death, was related to Jacob Frank’s messianic prophecies. Frank had been prophesying a “great war” to be followed by the overthrow of governments and foretold that the “true Jacob will gather the children of his nation in the land promised to Abraham.”[20] Gershom Scholem revealed that George Alexander Matuszewics, a Dutch artillery commander under Napoleon was the son of a leading Frankist.[21] Wenzel Zacek cited an anonymous complaint against Jacob Frank’s cousin, Moses Dobrushka—founder of the Asiatic Brethren—and his followers, which stated:

The overthrow of the papal throne has given their [the Frankists] day-dreams plenty of nourishment. They say openly, this is the sign of the coming of the Messiah, since their chief belief consists of this. [Sabbatai Zevi] was saviour, will always remain the saviour, but always under a different shape. General Bonaparte's conquests gave nourishment to their superstitious teachings. His conquests in the Orient, especially the conquest of Palestine, of Jerusalem, his appeal to the Israelites is oil on their fire, and here, it is believed, lies the connection between them and between the French society.[22]

Jozef Maria Hoene-Wronski (1776 – 1853)

According to Adam Mickiewicz (1798 – 1855), regarded as the greatest poet in all Polish literature, who was also a secret Frankist as well as a Martinist, there existed in France at the beginning of the nineteenth century, “a numerous Israelite sect, half Christian, half Jewish, which also looked forward to Messianism and saw in Napoleon the Messiah, at least his predecessor.”[23] These beliefs, notes Mickiewicz, were related to those of Jozef Maria Hoene-Wronski (1776 – 1853), a Polish philosopher and crackpot scientist. Sarane Alexandrian writes, in Histoire de la philosophie occulte, that “Wronski holds in occult philosophy the place that Kant holds in classical philosophy.”[24] Wronki’s brother-in-law was the Marquis Alexandre Sarrazin de Montferrier (1792 – 1863), who was the last Grand Master of the Order of the Temple, based on the Charter of Larmenius, which authorized by Napoleon in a solemn ceremony in 1808.[25]

In countries of Napoleon’s First French Empire conquered during the Napoleonic Wars, he emancipated the Jews and introduced other ideas of freedom from the French Revolution. Napoleon’s brief empire maintained an extensive military presence in Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Duchy of Warsaw, and counted Prussia and Austria as nominal allies. Napoleon overrode old laws restricting Jews to reside in ghettos, as well as lifting laws that limited Jews’ rights to property, worship, and certain occupations. In 1807, he designated Judaism as one of the official religions of France, along with Roman Catholicism, and Lutheran and Calvinist Protestantism.

Jewish emancipation, implemented under Napoleonic rule in French occupied and annexed states suffered a setback in many member states of the German Confederation following the decisions of the Congress of Vienna, following Napoleonic defeat and surrender in May 1814. While assimilation had set in earlier in other countries of Western Europe, such as France or Italy, in Germany it was given more significance because of the cultural prominence of the German Jews, who represented the largest Jewish group in Western Europe at that time.[26] Germany was one of the first countries which introduced the principle of legal equality for Jews. In fact, German Jews are seen as having been instrumental in paving the way for the “return of Jewry to Society.”[27] According to Jacob Katz, Germany has been considered as the “classic land of assimilation.”[28]

“Personal freedom (or at any rate an enlarged measure of it),” explained Isaiah Berlin, “economic opportunity, secular knowledge, liberal ideas, acted like a heady wine upon the children of the newly emancipated Jews.”[29] Many Jews became active politically and culturally within wider European civil society as Jews gained full citizenship. They emigrated to countries offering better social and economic opportunities, such as the Russian Empire and France. Some European Jews turned to Socialism, and others to Jewish Zionism. Haskalah resulted in the creation of secular Jewish culture, with an emphasis on Jewish history and Jewish identity, rather than religion. According to Gershom Scholem, “it is clear that a correct understanding of the Sabbatean movement after the apostasy of Sabbatai Zevi will provide a new clue toward understanding the history of the Jews in the 18th century as a whole, and in particular, the beginnings of the Haskalah (Enlightenment) movement in a number of countries.”[30] According to Jacob Katz, as an antinomian religion, Sabbateanism provided precedent for a type of Judaism that did not adhere to Jewish law, and in doing so paved the way for forms of non-observant Judaism such as the Haskalah and Zionism.[31] One source describes these effects as, “The emancipation of the Jews brought forth two opposed movements: the cultural assimilation, begun by Moses Mendelssohn, and Zionism, founded by Theodor Herzl in 1896.”[32]

Nathan the Wise

Illuminati publisher Christoph Friedrich Nicolai (1733 – 1811)

Rabbi Marvin S. Antelman declares that the tutor of Mendelssohn’s wife was Lessing’s good friend, Johann Joachim Christoph Bode, who became the de facto chief executive officer of the Illuminati, following Knigge’s resignation and Weishaupt’s flight, after the order was banned in Bavaria in 1784.[33] While working as a French ambassador in Berlin, the Comte de Mirabeau associated with the circle of Nicolai and was privy to Karl Friedrich Bahrdt’s “German Union” as well as the operations of the Wednesday Society’s Berlinische Monatsschrift and Nicolai’s Allgemeine Deutsche Bibliothek.[34] In Sur Mose Mendelssohn sur la Reforme Politique des Juifs (“Concerning Moses Mendelssohn on Political Reform of the Jews”), which appeared in London in 1787, Mirabeau argued that the faults of the Jews were rooted in their circumstances, and that the Jews could become useful citizens if they could abandon the “dark phantoms of the Talmudists.”[35] Likewise, Mendelssohn believed that the main problem facing Jews in Germany and throughout the rest of Europe at the time was that they lived isolated in ghettos, sent their children to Jewish schools and conducted their affairs in Yiddish. To improve the cultural, social, and economic status of the Jews of Germany, Mendelssohn advised Jews to assimilate them into the host culture.[36]

Mendelssohn’s friend, the Illuminati publisher Friedrich Nicolai, was the focal point of the Aufklärung, the German and Prussian Enlightenment, and along with Lessing and Mendelssohn, was largely responsible for its dissemination. In association with Nicolai, Mendelssohn established in 1757 the Bibliothek der schönen Wissenschaften, a periodical which he conducted until 1760. Lessing was the librarian of the Duke of Brunswick, Voltaire’s translator, and Mendelssohn’s closest friend. Mendelssohn’s first work, praising Leibniz, was printed with the help of the help of Lessing as Philosophical Conversations in 1755. Together with Lessing and Mendelssohn, Nicolai edited the famous book review journal Briefe, die neueste Literatur betreffend between 1759 and 1765, then from 1765 to 1792 he edited the Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek. Lessing and Christoph Bode were good friends and together in 1767 they created the J.J.C. Bode & Co. publishing firm in Hamburg.[37]

Lessing and Lavater as guests in the home of Moses Mendelssohn

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729 – 1781)

Lessing had portrayed a noble Jew in his play The Jews in 1749, and came to see Mendelssohn as the realization of his ideal. Subsequently, Lessing modeled him as the central figure of his drama Nathan the Wise, which features the Masonic theme of a universal religion. Set in Jerusalem during the Third Crusade, the book describes how the wise Jewish merchant Nathan, the enlightened sultan Saladin, and the initially anonymous Templar, bridge their gaps between Judaism, Islam and Christianity. The drama is also believed to have been in reference to Sabbatai Zevi’s patron, Nathan of Gaza. It has also been suggested that the inspiration for the character might also have been Jacob Falk, who was referred to in another work of Lessing, Ernst and Falk, his famous essay about Freemasonry.[38] According to Mendelssohn, the test of religion is its effect on conduct. This is the moral of the parable of the three rings from Lessing’s Nathan the Wise, which according to Frederick Beiser, “is indeed little more than a dramatic presentation of the philosophical doctrine of Spinoza’s Tractatus.”[39]

Mendelssohn’s knowledge had caused him to be known as “the German Socrates.”[40] In 1763, Mendelssohn won the prize of the Prussian Academy of Arts in a literary contest, and as a result King Frederick the Great of Prussia, Grand Master of Scottish Rite Freemasonry, was persuaded to exempt Mendelssohn from the limitations to which Jews were customarily subjected. An essay by Immanuel Kant came in second place. Mendelssohn’s most celebrated work, Phaedo, or on the Immortality of the Soul, referring to Plato’s Phaedo, defended the immortality of the soul against the materialism prevalent at the time. Mendelssohn himself published a German translation of the Vindiciae Judaeorum by Menasseh Ben Israel.

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804)

Kant wrote positively of Swedenborg, referring to his “miraculous” gift, and characterizing him as “reasonable, agreeable, remarkable and sincere” and “a scholar,” in one of his letters to his friend Moses Mendelssohn, and expressing regret at having never met him. Kant tried to later distance himself from Swedenborg, writing a mockery titled Dreams of a Spirit-Seer. However, there has long been suspicion among some scholars that Kant nevertheless held a secret admiration for Swedenborg.[41] Mendelssohn remarked that there was a “joking pensiveness” in Dreams that sometimes left the reader in doubt as to whether it was meant to make “metaphysics laughable or spirit-seeking credible.”[42]

Mendelssohn was a friend of the Swiss poet, writer, philosopher Johann Kaspar Lavater (1741 – 1801), whose works were studied by Illuminati initiates.[43] In 1769, Lavater sent Mendelssohn a translation of Charles Bonnet’s Palingénésie philosophique, and demanded that he either publicly refute Bonnet’s arguments or convert to Christianity. Mendelssohn refused to do either, and many prominent intellectuals took Mendelssohn’s side, including Lichtenberg and Illuminati member Johann Gottfried Herder. Nevertheless, when in 1775 the Swiss-German Jews, faced with the threat of expulsion, turned to Mendelssohn and asked him to intervene on their behalf with “his friend” Lavater, Lavater, after receiving Mendelssohn’s letter, promptly and effectively secured their stay. From 1774 on, Goethe was also intimately acquainted with Lavater, but later had a falling out with him, accusing him of superstition and hypocrisy.

Nicolai was among the founders of the Wednesday Society, internally known to members as the Society of Friends of Enlightenment (“Gesellschaft der Freunde der Aufklärung”). The Wednesday Society, which was a who’s who of Berlin Aufklärer, was one of several reading societies established by former members of the Illuminati, following Adam Weishaupt’s command:

The great strength of our Order lies in its concealment: let it never appear in any place in its own name, but always covered by another name, and another occupation… Next to [the first three degrees of Masonry] the form of a learned or literary society is best suited to our purpose, and had Free Masonry not existed, this cover would have been employed; and it may be much more than a cover, it may be a powerful engine in our hands. By establishing reading societies, and subscription libraries, and taking these under our direction, and supplying them through our labours, we may turn the public mind which way we will.[44]

Christian Wilhelm von Dohm (1751 – 1820)

A prominent member of the Wednesday Society was German historian Christian Wilhelm von Dohm (1751 – 1820), a staunch advocate for Jewish emancipation.[45] When Mendelssohn was asked by the Alsatian Jewish community to present the case for Jewish emancipation, but thought that such a work would produce a better results if written by a Christian, he requested Dohm to complete the task. Dohm, who wrote Concerning the Amelioration of the Civil Status of the Jews in 1781, asserted that the Jewish character had been corrupted by centuries of persecution, but that emancipation and assimilation into European society would improve them and eliminate known Jewish vices. According to Dohm, examples of Jewish corruption included “the exaggerated level… for every kind of profit, usury and crooked practices.” As a result, Jews were “guilty of a proportionately greater number of crimes than the Christians.” Such vices were “nourished” by Judaism, which was “antisocial and clannish” and nurtured “antipathy” towards gentiles.[46]

The interest caused by these publications led Mendelssohn to publish his most important contribution to the problems connected with the position of Judaism in a Gentile world, titled Jerusalem, or on Religious Power and Judaism, first published in 1783, which can be regarded as his most important contribution to Haskalah. The basic thrust of Jerusalem is that the state has no right to interfere with the religion of its citizens, Jews included. The first of the book’s two parts discusses “religious power” and the freedom of conscience in the context of the philosophies of Spinoza, Locke, and Hobbes, while the second part discusses Mendelssohn’s conception of the new secular role of any religion within an enlightened state. As with Spinoza, Jerusalem maintains the mandatory character of Jewish law, though it does not grant the rabbinate the right to punish Jews for deviating from it.

Kant, who described Jerusalem as “an irrefutable book,” called it “the proclamation of a great reform, which, however, will be slow in manifestation and in progress, and which will affect not only your people but others as well.”[47] According to the German-Jewish writer Heinrich Heine (1797 – 1856): “as Luther had overthrown the Papacy, so Mendelssohn overthrew the Talmud; and he did so after the same fashion, namely, by rejecting tradition, by declaring the Bible to be the source of religion, and by translating the most important part of it. By these means he shattered Judaism, as Luther had shattered Christian, Catholicism; for the Talmud is, in fact, the Catholicism of the Jews.”[48]

Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (1743 – 1819)

Mendelssohn would eventually become engaged in a final controversy, to defend Lessing against allegations made by fellow Illuminati member Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (1743 – 1819) that Lessing had supported the pantheism of Spinoza. Jacobi was insinuated into the Illuminati in 1782, becoming the Superior of the Illuminati in Düsseldorf.[49] After a conversation with Lessing in 1780, concerning Goethe’s then-unpublished pantheistic poem Prometheus, Jacobi embarked on an intense study of Spinoza and partook in debates with other philosophers over the matter. This led to the publication of Über die Lehre des Spinoza in Briefen an den Herrn Moses Mendelssohn [“On the Teaching of Spinoza in Letters to Mr. Moses Mendelssohn”] (1785), in which he criticized Spinozism as leading to atheism and rife with Kabbalism. The book denounced Lessing and Mendelssohn in particular, resulting a bitter feud, known as the pantheism dispute.

The entire issue, which Kant rejected, became a major intellectual and religious concern for European society at the time. Mendelssohn was thus drawn into an acrimonious debate, and found himself attacked from all sides, including former friends or acquaintances such as Illuminati member Herder. Mendelssohn’s contribution to this debate, To Lessing’s Friends 1786, was his last work, completed a few days before his death. When Mendelssohn died in 1786, Nicolai continued the debate on his behalf.

Frankfurt JudenLodge

David Friedländer (1750 – 1834)

Johann Christoph von Wöllner

Johann Rudolf von Bischoffwerder

Frederick William III was introduced to the Golden and Rosy Cross by Johann Christoph von Wöllner. Though not in name, Wöllner effectively became prime minister under Frederick William II. On July 3, 1788, Wöllner was appointed active privy councillor of state and of justice and head of the spiritual department for Lutheran and Catholic affairs, from which he was able to pursue extensive religion reforms in the Prussian state. On July 9, a religious edict was issued that stated that “enlightenment” had gone too far, and that the Christian church was in danger. On December 18, a new censorship law was issued to secure the orthodoxy of all published books. This forced major Berlin journals like Allgemeine Deutsche Bibliothek, by Illuminati publisher Friedrich Nicolai, and Johann Erich Biester’s Berliner Monatsschrift, to publish only outside of Prussia.[50] In addition, Immanuel Kant received a warning against speaking in public, stating that his Religion within the Bounds of Reason Alone, “abused […] philosophy for the purpose of distorting and disparaging several principle and fundamental doctrines of Holy Scripture.”[51] However, according to Christopher Clark, Wöllner’s policy was not to impose a new religious “orthodoxy,” as was often assumed, but rather to consolidate the existing religious structures. As a result, the edict was also a notable step forward in safeguarding the rights of Jews, Mennonites and the Moravia Church, who now received full state protection.[52]

Johann Rudolf von Bischoffwerder, who with Wöllner brought Frederick William II into the Golden and Rosy Cross, was part of the circle of contacts of Wolf Eybeschütz among the Asiatic Brethren, who played a leading role in the Haskalah, including Daniel Itzig (1723 – 1799), and Vienna bankers Nathan Arnstein and Bernhard Eskeles. [53] The Asiatic Brethren, founded by Jacob Frank’s cousin, Moses Dobrushka, also included among its member Rabbi Baruch ben Jacob Schick from Shklov (1744 – 1808), the Hebrew translator of Euclid and one of the pioneers of Haskalah of Eastern Europe.[54] After first serving as dayyan in Minsk, Schick traveled to London to study medicine and there joined the Freemasons. After qualifying as a doctor, Schick moved to Berlin where he became acquainted with the leaders of the Haskalah, including Moses Mendelssohn and Naphtali Herz Wessely (1725 – 1805), a student of Jonathan Eybeschuetz, who greatly influenced him.[55] Wessely was an alumnus of one of Rabbi Jonathan Eibeschutz’s seminaries, which as early as 1726 had been placed under a Rabbinical ban for their Sabbatian teachings.[56] In Berlin, Wessely met Moses Mendelssohn and contributed a commentary on Leviticus to the Biur, Mendelssohn’s translation of the Bible into German. Wessely is mainly known as a poet and advocate of the Enlightenment through his Divrei Shalom ve-Emet (1782), a call for support of Joseph II’s Edict of Tolerance.[57]

While the Jewish reform movement emerged in the nineteenth century, its beginnings lay really through the secular schools that began to be founded among the Jews in the closing decades of the eighteenth century.[58] The orthodox rabbis opposed to Mendelsshon’s translation of the Bible and Hartwig Wessely’s open letter to the Jews which advised them to educate their children along the lines laid down in the Joseph II’s Toleration Edict. The first of these schools in order of time was the Jewish Free School of Berlin, adverted to above as having been founded in I778 by German-Jewish banker David Friedländer (1750 – 1834) and his brother-in-law Isaac Daniel Itzig, both members of the Berlin Asiatic Brethren. Friedländer kept close contacts with Moses Mendelssohn and the circle of the Haskalah, who shared his emancipatory ambitions. Friedländer occupied a prominent position in both Jewish and non-Jewish circles of Berlin.

Between 1779 and 1781, Ephraim Joseph Hirschfeld (1755 – 1820), a Frankist and activist in Mendelssohn’s circle, and an active member of the Asiatic Brethren, worked in Berlin as a bookkeeper and Friedländer’s tutor. Hirschfeld was also close to Johann Georg Schlosser, the brother-in-law of Goethe. Hirschfeld and Moses Dobrushka met with Louis Claude de Saint Martin in 1793.[59] In 1784, Ecker und Eckhoffen took up residence in Vienna and he and Hirschfeld reorganized the Asiatic Brethren. Hirschfeld wrote of the Masonic Magic Flute by “the immortal Mozart,” a suspected member of the Asiatic Brethren, that it “will remain in all eternity: the canticum canticorum or the Sanctum sanctorum.”[60]

Ecker und Eckhoffen went to northern Germany in 1785 to seek the protection for the Asiatic Brethren from Ferdinand Duke of Brunswick and Illuminatus Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, whose support he had sought prior to the Congress at Wilhemsbad in 1782. The heads of the Freemasons had opposed the Asiatic Brethren, and by the end of that year, they had succeeded in persuading Joseph II to promulgate a law which would have placed all Masonic lodges under strict government supervision. In Schleswig, Ecker succeeded in gaining the sympathy of Prince Charles, who consented to become the Grand Master of the Order, and invited Ecker, and through him, Hirschfeld, to come and settle in Schleswig.[61]

Hirschfeld spent the remainder of his years in Offenbach where he retained close ties to the Frankists, including Asiatic Brethren, Franz Joseph Molitor (1779 – 1860). Molitor was “Christian Kabbalist” and active Freemason, who was influenced by Illuminati member Franz von Baader. Molitor’s philosophical efforts were intended to connect Kabbalah and Christianity and to unite them both on a new, higher level, an approach which is not unlike that of Hirschfeld, who believed that one could transcend Christian, Jewish, or Muslim beliefs and find “the one and only true, pure and overall religion.”[62]

Friedländer sought for the emancipation of the Jews of Berlin and various reforms. When Frederick William II, on his accession in 1786, called a committee to acquaint him with the grievances of the Jews, Friedländer was chosen among the general delegates. Friedländer was also concerned with endeavors to facilitate entry for himself and other Jews into Christian circles. In 1799, he made a radical proposal to a leading Protestant provost in Berlin, Wilhelm Teller, a member of the Wednesday Society.[63] Friedländer’s Open Letter, stated “in the name of some Jewish heads of families,” that Jews would be ready to undergo “dry baptism,” to convert to Protestant Christianity based of shared moral values, if they were not required to believe in the divinity of Jesus and avoid certain Christian rites. Much of the Open Letter argued that the Mosaic rituals were largely obsolete, and “envisioned the establishment of a confederated unitarian church-synagogue.”[64]

Itzig was a Court Jew of Kings Frederick II the Great and Frederick William II of Prussia. As one of the very few Jews in Prussia to receive full citizenship privileges, as a “Useful Jew,” Itzig became extraordinarily wealthy as a consequence. Itzig was a member of the wealthy banking firm of Itzig, Ephraim & Son, whose financial operations greatly assisted Frederick the Great in his wars.[65] At the instance of Moses Mendelssohn, Itzig, as the head of the Jewish community, interposed (April, 1782) in behalf of Wessely’s Worte der Wahrheit und des Friedens, which had been put under the ban by Polish rabbis.[66] Two of Itzig’s granddaughters married two of Moses Mendelssohn's sons. One of them was Lea, mother of Felix Mendelssohn and Fanny Hensel, a pianist and composer. Together with Friedlander, Itzig was appointed to lead a committee which was to discuss ways to improve the Jewish civil and social standing in Prussia, which led to the removal of many restrictions.

The Free School of Berlin and adjacent printing house later became one of the main institutions of the Haskalah movement. It inspired other schools, such as the Philanthropin in Frankfurt, founded in 1804 by the Rothschild banking house’s head clerk, Illuminati member Siegmund Geisenheimer (1775 – 1828). Geisenheimer founded at the Judenlodge in Frankfurt, which became the headquarters of leaders of the early Jewish Reform movement.[67] The local head Rabbi, Tzvi Hirsch Horowitz, excommunicated him from the city’s synagogue for setting up this lodge.[68] Geisenheimer was aided by Itzig, a member of the Illuminati of the Toleranz Lodge in Mainz and the Grand Orient in Paris.[69] The authorization from the Grand Orient was formally granted in 1807. The installation ceremony took place in 1808, when the lodge assumed the name of Loge de St. John de L’aurore Naissante (“Loge zur aufgehenden Morgenrothe”), Lodge of St. John of the Rising Dawn. Solomon Mayer Rothschild (1774 – 1855) joined the lodge for a short time before he moved to Vienna.[70] Although born a Christian, Franz Joseph Molitor was initiated into the lodge in 1808, which he fought to have recognized.[71]

Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel (1744 – 1836), member of the Illuminati, friend of Comte Saint-Germain and Grand Master of the Asiatic Brethren

Bijoux of the JudenLoge zur aufgehenden Morgenröthe

Since 1812, the Judenlodge had appointed Molitor as its head. Molitor’s friend Hirschfeld still maintained connections with Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, who had succeed the Duke of Brunswick as the head of all German Freemasons. Hirschfeld arranged for the two to meet, and Molitor set out for Schleswig, his mission being to obtain a new constitution and authorization for the lodge. Molitor returned with the constitution for a lodge of the first three degrees to be named after Saint John, and was given a document authorizing the formation of a lodge to be conducted according to the Scottish rite, to which the lodge of Saint John would be subordinate.[72] In 1817, the Judenlodge obtained a new charter from Prince Charles. Its Christian members separated and formed Frankfurt Lodge Carl the Rising Light, also from Prince Charles, while the Judenlodge lodge received a constitution from the Great Lodge in England.[73]

During its formative years, the three most active members of the Judenlodge were Geisenheimer, Michael Hess (1782 – 1860) and Justus Hiller (1760 – 1833). Michael Hess was hired by Mayer Amschel Rothschild as a tutor for his children.[74] Hess became headmaster of Philanthropin. Justus Hiller was appointed orator of the Lodge. At its founding, his antinomian leanings were evident in his address, where he alluded to Frankist teachings.[75] Philanthropin also received substantial financial support from high-ranking Illuminati member, Baron Karl Theodor von Dalberg (1744 – 1817), the brother of Wolfgang Heribert von Dalberg, the director of the Mannheim Theatre. Baron Karl Theodor von Dalberg was Prince-Archbishop of Regensburg, Arch-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire, Bishop of Constance and Worms, prince-primate of the Confederation of the Rhine and Grand Duke of Frankfurt. Dalberg was also a notable patron of letters, and was the friend of Goethe, Schiller and Christoph Martin Wieland (1733 – 1813), a representative of the cosmopolitanism of the German Enlightenment, whose work was recommended reading among the Illuminati.[76] According to Niall Ferguson, Mayer Amschel Rothschild was acting as Dalberg’s “court banker.”[77] In 1811, Dalberg enacted a special law “decreeing that all Jews living in Frankfort, together with their descendants, should enjoy civil rights and privileges equally with other citizens.”[78] In exchange for these new liberties, the Jews had to pay Dalberg 440,000 florins, financed by Mayer Amschel Rothschild. A number of Jewish Freemasons at the time also petitioned Dalberg for the “exclusive right to maintain lodges in the city.”[79]

Hamburg Temple

The Hamburg Temple in its original edifice, at the Brunnenstraße.

Israel Jacobson (1768 – 1828)

Illuminati member Goethe labelled Israel Jacobson (1768 – 1828) “Jacobin, son of Israel.”[80] Jacobson became the founder of the Jewish Reform movement in connection with the foundation of the school at Seesen in 1801. An intermediate consequence of Haskalah’s call to modernize the Jewish religion was the emergence of Reform Judaism in Germany in the early nineteenth century. The first permanent Reform synagogue was the Hamburg Temple in Germany, where the New Israelite Temple Society (Neuer Israelitischer Tempelverein) was founded in 1817. One of the pioneers of the synagogue reform was Israel Jacobson, who had studied the works of Lessing and Mendelssohn. At the age of eighteen, after having accumulated a small fortune, he married into the Samson family, through whom he became friends with Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick and Lunenburg, Prince of Wolfenbüttel (1735 – 1806), favorite nephew of Frederick II of Prussia, and the uncle of Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Grand Master of the Strict Observance.

Charles William was an ardent Freemason and entered into friendly relations with the Grand Lodge of English.[81] He was also regarded as a benevolent despot, and was married to Princess Augusta of Great Britain, daughter of Frederick, Prince of Wales and his wife, Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, and sister of the reigning King George III. Princess Augusta of Saxe-Gotha was the sister of Frederick II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1676 – 1732), the father of Illuminati member Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, the grandfather of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. In 1766, Charles William and his wife Princess Augusta travelled to Switzerland and met with Voltaire.[82]

Friedrich Wilhelm III of Prussia (1770 –1840)

When, under Napoleon’s rule, the Kingdom of Westphalia was created, and the emperor’s brother Jérôme Bonaparte was placed at its head, Jacobson was appointed president of the Jewish consistory, the Royal Westphalian Consistory of the Israelites, established in 1808. In countries of Napoleon’s First French Empire conquered during the Napoleonic Wars, he emancipated the Jews and introduced other ideas of freedom from the French Revolution. Napoleon’s brief empire maintained an extensive military presence in Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Duchy of Warsaw, and counted Prussia and Austria as nominal allies. Napoleon overrode old laws restricting Jews to reside in ghettos, as well as lifting laws that limited Jews’ rights to property, worship, and certain occupations. In 1807, he designated Judaism as one of the official religions of France, along with Roman Catholicism, and Lutheran and Calvinist Protestantism.

Jewish emancipation, implemented under Napoleonic rule in French occupied and annexed states suffered a setback in many member states of the German Confederation following the decisions of the Congress of Vienna, following Napoleonic defeat and surrender in May 1814. While assimilation had set in earlier in other countries of Western Europe, such as France or Italy, in Germany it was given more significance because of the cultural prominence of the German Jews, who represented the largest Jewish group in Western Europe at that time.[83] Germany was one of the first countries which introduced the principle of legal equality for Jews. In fact, German Jews are seen as having been instrumental in paving the way for the “return of Jewry to Society.”[84] According to Jewish historian Jacob Katz, Germany has been considered as the “classic land of assimilation.”[85]

In that capacity, Jacobson worked to exercise a reforming influence upon the various congregations of the country. Jacobson played an influence in the outcome of the Emancipation Edict of 1812, issued by Frederick William III, which gave the Jews of Prussia partial citizenship, and after Jews served as soldiers for the first time. Frederick William III, the son of Golden and Rosy Cross member Frederick William II, was also a Freemason.[86] In 1816, Jacobson swore an oath of fealty to Frederick Francis I, Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, thus becoming the first Jew with a permanent seat and vote in the Estates of the Realm of a German state. After Napoleon’s fall in 1815, Jacobson moved to Berlin, where he continued to introduce reforms in beliefs and divine service.

While Orthodox protests to Jacobson’s initiatives were few, dozens of rabbis throughout Europe united to denounce the Hamburg Temple as heretics. The overwhelming Orthodox reaction halted the progress of the reform trend, confining it to the port city for the next twenty years.[87] The New Temple Society invited the grandson of Moses Mendelssohn, the Hamburg-born Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy to set Psalm 100 to music for a choir for playing it at the inauguration of the new Temple on September 5, 1844.[88]

Reformed Society of the Israelites

Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in Charleston, the colony’s first synagogue, founded in 1749, played a significant role in bringing Reform Judaism to the United States, a tradition which Rabbi Marvin Antelman has linked to the Sabbatean Movement.

In 1824, the Reformed Society of the Israelites was founded in Charleston by Portuguese Jews, led by Isaac Harby, who dissented from Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim synagogue. Harby was descended from a family that had fled Spain for Portugal and then Morocco, London, and Jamaica before moving to Charleston in 1782. Harby’s father Solomon married Rebecca Moses, the daughter of one of South Carolina’s leading Jewish families. Harby and his fellow reformers thought that services at Beth Elohim had to become more like those services in surrounding Protestant churches. The leaders of Beth Elohim refused to consider their petition to amend synagogue rituals or practices. Thomas Jefferson wrote to say that he found Harby’s reforms proposed “entirely reasonable,” though confessing that he was “little acquainted with the liturgy of the Jews or their mode of worship.”[89] In response, the reformers created an independent society, which met in Seyle’s Hall, a facility also rented by the Grand Lodge, Ancient Free Masons of South Carolina. Seyle himself was a member of Orange Lodge, No. 14.[90] Harby left Charleston for New York in 1827. Although the Society never officially disbanded, it ceased to exist sometime after the mid-1830s. Most members rejoined Beth Elohim.

However, the spirit of reform in Charleston did not die with Harby. In 1836, Gustavus Poznanski (1804 – 1879) was appointed minister. Poznanski spent time in Hamburg and later in Bremen learning about Reform before emigrating to the United States in 1831.[91] In 1838, Beth Elohim synagogue burned and when the new building was constructed an organ was introduced, the first organ ever used in an American synagogue. Known as the "Great Organ Controversy,” it divided the synagogue and the case was taken to court by forty members who had left the congregation because of their objection. Thus, Beth Elohim became the first synagogue in America to provide organ music at services. This break with the orthodox tradition opened the way for other changes in the ritual, many of which had been requested a decade earlier by the Reformed Society. Beth Elohim thereafter evolved at the forefront of reform Judaism in America.[92]

At the dedication of the new synagogue building in 1841, Poznanski famously said, “This synagogue is our temple, this city our Jerusalem, this happy land our Palestine, and as our fathers defended with their lives that temple, that city and that land, so will their sons defend this temple, this city and this land.”[93] He added, “America is our Zion and Washington our Jerusalem.”[94] When Poznanski recommended the abolition of the second day of Jewish Festivals more members withdrew. Poznanski offered to step aside to bring peace but returned to the pulpit for four additional years until 1847. After retirement, Poznanski divided his time between Charleston and New York, where he was a member of Shearith Israel, a synagogue that had maintained extensive connections with Mikveh Israel in Philadelphia, many of whose members belonged to the Rite of Perfection who played a significant role in the American Revolution.[95]

Reform Judaism

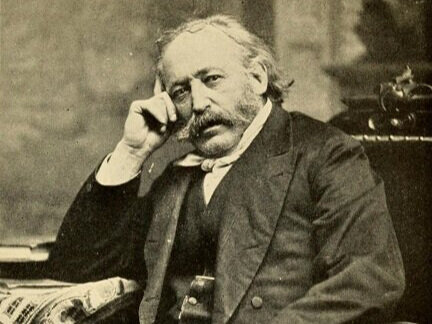

Isaac Mayer Wise (1819 – 1900), a Scottish Rite Freemason, wrote wrote “Masonry is a Jewish institution whose history, degrees, charges, passwords, and explanations are Jewish from the beginning to the end.”

Poznanski’s successor was not be chosen until 1850 because the community remained divided. Among those who applied for the position was Scottish Rite Mason, Isaac Mayer Wise. Wise, the “Moses of America” as some called him, was born in Bohemia and undertook secular studies at the Jew Theological Seminary in Prague. He became a rabbi of a small synagogue, but his teachings became regarded as revolutionary. When he came under suspicion of the Austrian authorities for his pronouncements, he decided to emigrate to America in 1846, and was offered a post as rabbi of the Beth-El Congregation in Albany. Here too he announced his intention to reform Judaism, which had a decidedly Sabbatean tone to it: “Religion is intended to make man happy, good, just, active, charitable, and intelligent. Whatever tends to this end must be retained or introduced. Whatever opposes it must be abolished.”[96] In 1850 he made a trip to Charleston, and when he was asked by the congregants of Kahal Kadosh whether he believed in the coming of a Messiah and the resurrection of the body, Wise unhesitatingly answered, “No, the Talmud is no authority for me in the matter of doctrine.”[97] Wise returned to Albany, but he was again challenged for his views. His followers seceded from the synagogue and founded a Reform congregation called Anshe Emeth.

Following a storm of controversy, Wise accepted a post at the Bene Yeshurun Congregation in Cincinnati. Shortly after his move, he began the weekly newspaper The Israelite (after 1874 The American Israelite), and a German-language supplement for women, Die Deborah. In August 1855, Wise published a response in The Israelite to a letter which had been published in The Boston Morning Times from an anonymous Mason from Massachusetts, in which he had claimed: “… here in Massachusetts Masonry is a Christian, or rather Protestant institution ; Christian, as it merely TOLERATES Jews ; Protestant, as it abhors Catholics.” Wise countered:

We characterize the above principles as anti Masonic, because we know that not only Catholics but Israelites in this country and in Europe are prominent and bright Masons. We know still more, viz. that Masonry is a Jewish institution whose history, degrees, charges, passwords and explenations (sic) are Jewish from the beginning to the end, with the exception of one by-degree and a few words in the obligation, which true to their origin in the middle ages, are Roman Catholic. (…) it is impossible to be well posted in Masonry without having a Jewish teacher.[98]

Two weeks later, Wise published a response from “A Young Mason” from Boston, Massachusetts, who asserted that Rev. Brother Randall insisted that Masonry “was once mainly Jewish but now it is mainly Christian.” Wise’s sarcastic response was:

It is a great favour, the Rev. R. believes that the Jews are admitted in the lodges etc. of which they must be sensible and grateful. Why does he not consider it a favor, that we have the privilege of living in our houses. Masonry was founded by Jews as a cosmopolitical institution, hence it is a favor for the Jew to be admitted in the lodges, viz. in our own house. How sapient!

We Jews have given birth to the masonic fraternity as a cosmopolitical institution; but we consider it no favor to admit you in the lodge, provided, however, you leave your sectarianism outside of the consecrated walls. We have given you Christianity to convert the heathens gradually to the pure deism and ethics of Moses and the Prophets; still, we consider it no special favor bestowed on you from our side, that you have the privilege of being a preacher in one of the churches.[99]

Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, in Cincinnati, Ohio

Wise made Cincinnati the center of his Reform movement for the continent, visiting all the chief cities in the country, from New York to San Francisco, to propagate his ideas for reform. In 1873, delegates of many reform congregations met in Cincinnati and organized the Union of American Hebrew Congregations and the Hebrew Union College, of which Wise became President. Finally, in 1889, Wise’s dream of uniting the American congregation resulted in the establishment of the Central Conference of American Rabbis (CCAR), which succeeded in publishing a uniform prayer book in use in most of the reform congregations. CCAR became the principal organization of Reform rabbis in the United States and Canada. The CCAR primarily consists of rabbis educated at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, located in Cincinnati, Ohio, New York City, Los Angeles, and Jerusalem.

Wise visited President Buchanan to protest against the treatment of Jews in Switzerland. He called on President Lincoln to object to General Grant’s Order No. 2. He also headed a delegation which asked President Hayes to protect the rights of American Jews in Russia. Politically, a strong opponent of slavery, Wise developed into an ardent States Rights Democrat. He was a member of the Cincinnati Board of Education and of the Board of Directors of the University of Cincinnati.[100]

Conservative Judaism

Zecharias Frankel (1801 – 1875), Frankist and founder of Conservative Judaism

Reform Judaism is now the largest denomination of American Jews. Rabbi Antelman’s research has demonstrated that according to Reform Judaism—reflecting the Frankist rejection of the Torah—almost everything connected with traditional Jewish ritual law and custom is of the ancient past, and thus no longer appropriate for Jews to follow in the modern era. As Rabbi Antelman remarks, “and so the curse of insipid Gnosticism pervades the holy house of Israel and exists within its midst as a fifth column of destruction.”[101] It was Rabbi Antelman, in To Eliminate the Opiate, who pointed out that the Frankists introduced Sabbateanism on a large-scale in Judaism principally through the Reform and Conservative movements, as well as Zionist-leaning organizations like the American Jewish Congress, the World Jewish Congress and the B’nai B’rith, Hebrew for “Sons of the Covenant.” The B’nai B’rith, the oldest Jewish service organization in the world, was established in 1843 by several German Jews living in New York who were members of the Freemasons or Odd Follows, as well as several secret fraternal societies. [102]

Solomon Schechter (1847 – 1915), Frankist and founder of the American Conservative Jewish Movement

A Frankist by the name of Rabbi Zecharias Frankel (1801 – 1875), the founder of Conservative Judaism, separated from the Reform movement, which he regarded as too radical, in order to make his attack on Judaism from a different front by supposedly calling for a return to Jewish law.[103] However, according to Frankel, Jewish law was not static, but had always developed in response to changing conditions. He called his approach towards Judaism “Positive-Historical,” which meant that one should accept Jewish law and tradition as normative, yet one must be open to changing and developing the law in the same fashion that Judaism has always historically developed.

Frankel was also the mentor to another Frankist, a Moldavian-born Romanian and English rabbi, Solomon Schechter (1847 – 1915), the founder of the American Conservative Jewish Movement. Although Schechter emphasized the centrality of Jewish law saying, “In a word, Judaism is absolutely incompatible with the abandonment of the Torah,” he nevertheless believed in what he termed Catholic Israel.[104] The basic idea was that Jewish law is formed and evolves based on the behavior of the people, and it is alleged that Schechter openly violated the prohibitions associated with traditional Sabbath observance.[105]

Rome and Jerusalem

Moses Hess (1812 – 1875)

Moses Hess (1812 – 1875) was one of the first important leaders of the Zionist cause, being regarded as the founder of Labor Zionism, originally advocating Jewish integration into the socialist movement. Hess was the grandson of Rabbi David T. Hess who succeeded to the Rabbinate of Manheim, after it had been seized by the Sabbatean followers of Rabbi Eybeschütz.[106] Hess was a great admirer of Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic rabbis, who according to him lived in a “socialistic fashion,” and whose philosophical aspect, from the point of view of the theoretical Kabbalah, he explained, is developed in the Tanya. Hess observed:

The great good which will result from a combination of Hasidism with the national movement (secular Zionists) is almost incalculable… Even the rabbis, who heretofore have declared Chasidism a heresy, are beginning to understand that there are only two alternatives for the great Jewish masses of Eastern Europe; either to be absorbed along with the reformers, by the gradually penetrating external culture, or to avert this catastrophe by an inner regeneration of which Hasidism is certainly a forerunner.[107]

In 1862, Hess published Rome and Jerusalem: A Study in Jewish Nationalism, which calls for the establishment of a Jewish socialist commonwealth in Palestine. According to Hess, there are two epochs that mark the development of Jewish law: the first followed the exodus from Egypt, and the second the return from Babylon. However, according to Hess, in the ensuing centuries, the Jewish reformers were motivated by other than patriotic motives. With the third epoch still to come, which will be the redemption from the third exile, the Jewish reformers will rediscover the “the Jewish genius,” and restore the restoration of the Jewish State.

The “Jewish genius” represents the Jews ability to intellectualize their religion, without being restrained by tradition. In Rome and Jerusalem, Hess explains this process, providing justification for the usurpation of orthodox Judaism by the reformers:

Judaism is not threatened, like Christianity, with danger from the nationalistic and humanistic aspirations of our time, for in reality, these sentiments belong to the very essence of Judaism. It is a very prevalent error, most likely borrowed from Christianity, that an entire view of life can be compressed into a single dogma. I do not agree with Mendelssohn that Judaism has no dogmas. I claim that the divine teaching of Judaism was never, at any time, completed and finished. It has always kept on developing, its development being based upon the harmonizing of the Jewish genius with that of life and humanity. Development of the knowledge of God, through study and conscientious investigation, is not only not forbidden in Judaism, but is even considered a religious duty. This is the reason why Judaism never excluded philosophical thought or even condemned it, and also why it has never occurred to any good Jew to “reform” Judaism according to his philosophical conceptions. Hence there were no real sects in Judaism. Even recently, when there was no lack of orthodox and heterodox dogmatists in Jewry, there arose no sects; for the dogmatic basis of Judaism is so wide, that it allows free play to every mental speculation and creation. Differences of opinion in regard to metaphysical conceptions have always obtained among the Jews, but Judaism has never excluded anyone. The apostates severed themselves from the bond of Jewry. “And not even them has Judaism forsaken,” added a learned rabbi, in whose presence I expressed the above quoted opinion.[108]

According to Hess, therefore, Saadia Gaon, Maimonides, Spinoza and Mendelssohn did not become apostates, despite the numerous protests against their “progressive” interpretations, and though the “modern rationalists,” referring to Orthodox Jews, would excommunicate the Spinozists if they could. According to Hess, Spinoza was “latest expression of the Jewish genius,” and the true prophet of the messianic movement of Sabbatai Zevi.[109] Developing on the thought of Spinoza, Hegel and Schopenhauer, Hess constructed a materialistic idea of human progress. It was Spinoza, explained Hess, who conceived Judaism as grounded in nationalism. In line with the emerging national movements across Europe, Hess believed that the Jews too would rebel against the existing order, fortified by their “racial instinct” and by their “cultural and historical mission to unite all humanity in the name of the Eternal Creator.”[110]

Hess denounces the Orthodox opinion that insists on the view of Judaism as a religion. According to Hess, Judaism is a nationality, “which is inseparably connected with the ancestral heritage and the memories of the Holy Land, the Eternal City, the birthplace of the belief in the divine unity of life, as well as the hope in the future brotherhood of men.”[111] Hess asserts that every Jew has within him the potentiality of a Messiah, while every Jewess that of a “Mater dolorosa,” one of the names of the Virgin Mary, referred to in relation to the Seven Sorrows of Mary popular among Roman Catholics, and a key subject for Marian art in the Catholic Church.

[1]. Dr. Isaac Wise. The Israelite (August 3 and 17, 1855); quoted in Samuel Oppenheim. The Jews and Masonry in the United States before 1810. Reprint from Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, 19 (1910), 1-2.

[2] “The Story of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim of Charleston, SC.” Retrieved from https://images.shulcloud.com/1974/uploads/Documents/The-Story-of-KKBE

[3] Samuel Oppenheim. “The Jews and Masonry in the United States Before 1810.” American Jewish Historical Quarterly, Vol 19 (1910).

[4] Rabbi Marvin Antelman. To Eliminate The Opiate, Vol. 2.

[5] David Shavin. “Philosophical Vignettes from the Political Life of Moses Mendelssohn” FIDELIO Magazine, Vol . 8, No. 2, Summer 1999; Pawel Maciejko. The Mixed Multitude (University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc.. Kindle Edition), p. 195 n. 95.

[6] Kerem Chemed. Volume III, pp. 224-225.

[7] Jacob Adler. “The Zionists and Spinoza.” Israel Studies Forum, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Spring 2009), pp. 25-38.

[8] Samson Raphael Hirsch. Religion Allied to Progress, in JMW. p. 198; Cohn-Sherbok, Dan. Judaism: History, Belief, and Practice (Routledge, 2004). p. 264.

[9] Leo Strauss. Spinoza’s Critique of Religion. Translated by E. M. Sinclair. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

[10] Richard H. Popkin.“Benedict de Spinoza.” Encyclopædia Britannica. (Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., May 12, 2019). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Benedict-de-Spinoza

[11] Cited in Kelly Devine Thomas. “Spinoza and The Origins of Modern Thought.” Historical Studies. Institute for Advanced Study. The Institute Letter Winter 2007. Retrieved from https://www.ias.edu/ideas/2007/israel-spinoza

[12] Encyclopedia Judaica, p. 1443, cited in Shira Schoenberg. “Modern Jewish History: The Haskalah.” Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved from https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-haskalah#4

[13] Shmuel Ettinger. In A History of the Jewish People, (ed.) H.H. Ben-Sasson (Harvard University Press, 1976).

[14] Jacob Katz. Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723-1939, p. 47.

[15] Melanson. Perfectibilists (Kindle Locations 5719-5720).

[16] “Sonnenfels, Aloys von.” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[17] Charles W. Ingrao. The Habsburg Monarchy, 1618-1815 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 1999.

[18] M. B. Goldstein. The Newest Testament: A Secular Bible (ArchwayPublishing, 2013), p. 592.

[19] Jacob Katz. “Israel and the Messiah.” Commentary, 36 (January 1982).

[20] Duker. “Polish Frankism’s Duration,” p. 308

[21] Ibid., p. 310

[22] Ibid., p. 308

[23] Duker, “Polish Frankism’s Duration,” p. 292.

[24] Sarane Alexandrian. Histoire de la philosophie occulte (Paris: Seghers, 1983) p. 133.

[25] Paul Chacornac. Eliphas Lévi, rénovateur de l'occultisme en France (1810-1875). (Editions Traditionnelles, 1989), p. 136.

[26] Marion Berghahn. German-Jewish Refugees in England (London: MacMillan Press, 1984), p. 40.

[27] Hans Liebeschi.itz, “Judentum und deutsche Umwelt im Zeitalter der Restauration,” Hans Liebeschiitz and Arnold Paucker (eds), Das Judentum in der deutschen Umwelt, 1800-1850 (Tiibingen, 1977) p. 2; cited in Marion Berghahn. German-Jewish Refugees in England (London: MacMillan Press, 1984), p. 40.

[28] Jacob Katz. Emancipation and Assimilation (Westmead, 1972) p. x; cited in Berghahn. German-Jewish Refugees in England, p. 40.

[29] Isaiah Berlin. The Life and Opinions of Moses Hess (Jewish Historical Society of England, 1959), p. 214.

[30] Gershom Scholem. “Redemption Through Sin,” The Messianic Idea in Judaism and Other Essays, pp. 78–141.

[31] Jacob Katz. “Regarding the Connection of Sabbatianism, Haskalah, and Reform.” Studies in Jewish Religious and Intellectual History. ed. Siegfried Stein and Raphael Loewe (Tuscaloosa, Ala: University of Alabama Press, 1979) p. 83-101; from M. Avrum Ehrlich. “Sabbatean Messianism as Proto Secularism.” Jewish Encounters, (Haarlem, 2001).

[32] “Jews,” William Bridgwater, ed. The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopedia; second ed., (New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1964), p. 906.

[33] Rabbi Marvin Antelman. To Eliminate The Opiate, Vol. 1 (Zionist Book Club, 2004), p.76.

[34] Terry Melanson. “10 Notable Members of the Bavarian Illuminati.” Conspiracy Archive (September 20, 2015).

[35] Cited in Antelman. To Eliminate The Opiate, Vol. 1.

[36] “Mendelssohn, Moses.” World Religions Reference Library. Encyclopedia.com.

[37] Melanson. Perfectibilists (Kindle Locations 5737-5738).

[38] Webster. Secret Societies and Subversive Movements, p. 192.

[39] Frederick. C. Beiser. The Fate of Reason: German Philosophy from Kant to Fichte (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1987), p. 56; Cited in Magee. Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition, p. 77, n. 155.

[40] Israel Abrahams. “Mendelssohn, Moses.” In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). (Cambridge University Press, 1911) pp. 120–121.

[41] Ernst Benz. Emanuel Swedenborg: Visionary Savant in the Age of Reason (Swedenborg Foundation, 2002), p. xiii.

[42] G. Johnson, ed. Kant on Swedenborg. Dreams of a Spirit-Seer and Other Writings. Translation by Johnson, G., Magee, G.E. (Swedenborg Foundation 2002) p. 123.

[43] Melanson. Perfectibilists.

[44] Ibid. (Kindle Locations 1405-1409).

[45] Ibid. (Kindle Locations 1450-1451).

[46] Cited in Jacques Kornberg. Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism (Indiana University Press, 1993), p. 17.

[47] Israel Abrahams. “Mendelssohn, Moses.” In Hugh Chisholm (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 18, 11th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1911), p. 121.

[48] Heinrich Heine. Religion and Philosophy in Germany, A fragment (Beacon Press, 1959), p. 94.

[49] Ibid.

[50] “Preussenchronik: Der neue König macht wenig besser und vieles schlimmer.” Preusen: Chronik Eines Deutsches Staates. (May 21, 2008). Retrieved from https://www.preussenchronik.de/ereignis_jsp/key=chronologie_003870.html

[51] Christopher Clark. Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600 to 1947 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006). pp. 270.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Pawel Maciejko. “A Portrait of the Kabbalist as a Young Man: Count Joseph Carl Emmanuel Waldstein and His Retinue.” The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 106, No. 4 (Fall 2016), p. 568.

[54] Pawel Maciejko. The Mixed Multitude (University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc.. Kindle Edition), p. 226.

[55] Zeitlin. Bibliotheca; Zinberg. Sifrut, 3 (1958), 325–8; Twersky, in: He-Avar, 4 (1956), 77–81; R. Mahler. Divrei Yemei Yisrael, 4 (1956), 53–56; B. Katz. Rabbanut, Ḥasidut, Haskalah, 2 (1958), 134–9; N. Schapira, in: Harofe Haivri, 34 (1961), 230–5; J. Katz. Jews and Freemasons (1970).

[56] Alexander Altmann. Moses Mendelssohn: A Biographical Study (University of Alabama Press, 1973), pp. 453.454; cited in Antelman. To Eliminate the Opiate, vol. 1

[57] Joshua Barzilay. “Wessely, Naphtali Herz.” Encyclopaedia Judaica.

[58] David Philipson. “The Beginnings of the Reform Movement in Judaism.” The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Apr., 1903), p. 485.

[59] Katz. Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723-1939, p. 53.

[60] M.F.M. Van Den Berk. The Magic Flute (Leiden: Brill, 2004), p. 507.

[61] Ibid., Chapter III.

[62] Rabbi Antelman. To Eliminate the Opiate, Vol. I.

[63] Melanson. Perfectibilists (Kindle Location 1465).

[64] Amos Elon. The Pity of It All: A History of the Jews in Germany, 1743-1933 (Metropolitan Books, 2002), pp. 73-75

[65] Peter Wiernik, I. George Dobsevage, Isidore Singer. “ITZIG (sometimes Hitzig).” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Antelman. To Elimijnate the Opiate, vol. 1.

[68] Augustin Barruel. Memoirs Illustrating the History of Jacobinism, Part II.

[69] Jacob Katz. Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723-1939 (Harvard, 1970), pp. 58-59.

[70] Ibid.

[71] “Zur aufgehenden Morgenröthe.” Masonic Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://freimaurer-wiki.de/index.php/Zur_aufgehenden_Morgenr%C3%B6the; “Molitor, Franz Joseph.” Encyclopaedia Judaica. Encyclopedia.com.

[72] Katz. Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723-1939, Chapter 4.

[73] “History of Freemasonry in Germany.” The American Freemason’s New Monthly Magazine, Volume 8 (J.F. Brennan, 1856), p. 129; Zur aufgehenden Morgenröthe. Masonic Encyclopedia. Retrieved from https://freimaurer-wiki.de/index.php/Zur_aufgehenden_Morgenr%C3%B6the

[74] Jacob Katz. Jews and Freemasons in Europe 1723-1939 (Harvard, 1970), p. 91

[75] Isidor Kracauer. Geschichte der Juden in Frankfurt (Frankfurt, 1927) II, pp. 355-421; cited in Antelman. To Elimijnate the Opiate, vol. 1.

[76] Hugh Chisholm, ed. “Dalberg § 2. Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg.” Encyclopædia Britannica. 7, 11th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1911). pp. 762–763; Melanson. Perfectibilists. Kindle Locations 3930-3931..

[77] Melanson. Perfectibilists. Kindle Locations 6176-6177.

[78] Ibid. Kindle Locations 6170-6175.

[79] Ibid. Kindle Locations 6170-6175.

[80] Antelman. To Illuminate the Opiate, vol. 1, p. p. xix.

[81] “Frederick the Great, and His Relations with Masonry and Other Secret Societies” The Builder (1921). Retrieved from https://www.masonicworld.com/education/files/ftgandhisrelationswmasonry.htm

[82] Hugh Chisholm, ed. “Brunswick, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of.” Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1911).

[83] Marion Berghahn. German-Jewish Refugees in England (London: MacMillan Press, 1984), p. 40.

[84] Hans Liebeschi.itz, “Judentum und deutsche Umwelt im Zeitalter der Restauration,” Hans Liebeschiitz and Arnold Paucker (eds), Das Judentum in der deutschen Umwelt, 1800-1850 (Tiibingen, 1977) p. 2; cited in Marion Berghahn. German-Jewish Refugees in England (London: MacMillan Press, 1984), p. 40.

[85] Jacob Katz. Emancipation and Assimilation (Westmead, 1972) p. x; cited in Berghahn. German-Jewish Refugees in England, p. 40.

[86] George William Speth. Royal Freemasons (Masonic Publishing Company, 1885), p. 27.

[87] Michael A. Meyer. Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism (Wayne State University Press, 1995).

[88] Eric Werner. “Felix Mendelssohn’s Commissioned Composition for the Hamburg Temple. The 100th Psalm (1844),” in: Musica Judaica, 7/1 (1984–1985), p. 57.

[89] Michael Feldberg. “Isaac Harby.” My Jewish Learning. Retrieved from https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/isaac-harby/

[90] “Reformed Society of Israelites.” Mapping Jewish Charleston. Retrieved from https://mappingjewishcharleston.cofc.edu/1833/map.php?id=1036

[91] Michael A. Meyer. Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism (Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1995), p. 233-234.

[92] Michael Feldberg. “Isaac Harby.” My Jewish Learning. Retrieved from https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/isaac-harby/

[93] Meyer. Response to Modernity, p. 233-234.

[94] Robert Laurence Moore. Religious outsiders and the making of American (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 79.

[95] David Livingstone. Ordo ab Chao. Volume One: “The American Revolution.”

[96] "Career of Rabbi Wise.” New York Times (March 27, 1900).

[97] Ibid.

[98] Rabbi Wise. The Israelite (August 3, 1855)

[99] Ibid.

[100] “Career of Rabbi Wise.” New York Times (March 27, 1900).

[101] Rabbi Antelman. To Eliminate the Opiate. Volume 2 (Jerusalem: Zionist Book Club, 2002), p. 102.

[102] Edward E. Grusd. B’nai B’rith; the story of a covenant (New York: Appleton-Century, 1966), pp. 12-13.

[103] Ibid., p. 135.

[104] Inaugural address as President of the JTSA in 1902.

[105] American Hebrew 57:18 (6 September 1895), p. 60.

[106] Antelman. To Eliminate the Opiate, Volume 2., p. 20.

[107] Moses Hess. The Revival of Israel: Rome and Jerusalem (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, p. 248.

[108] Moses Hess. Rome and Jerusalem: A Study in Jewish Nationalism (New York: Bloch Publishing Company, 1918), pp. 96-97.

[109] Ibid., p. 83.

[110] Hess. Rome and Jerusalem, p. 36.

[111] Hess. The Revival of Israel, p. 45.

Volume Two

The Elizabethan Age

The Great Conjunction

The Alchemical Wedding

The Rosicrucian Furore

The Invisible College

1666

The Royal Society

America

Redemption Through Sin

Oriental Kabbalah

The Grand Lodge

The Illuminati

The Asiatic Brethren

The American Revolution

Haskalah

The Aryan Myth

The Carbonari

The American Civil War

God is Dead

Theosophy

Shambhala