19. God is Dead

Darwinism

For all the propaganda of the Enlightenment which succeeded in largely discrediting Christianity, and religion in general, no attack has been as devastating as that of Darwinism. However, despite popular misconceptions, Darwinism is still an unproven theory. Rather, Darwinism is fundamentally a religious idea, and an attempt to demonstrate scientifically that the universe conforms to the Lurianic Kabbalah, where man is evolving to become God. According to Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (1865 – 1935), the most important exponent of Religious Zionism, evolution “is increasingly conquering the world at this time, and, more so than all other philosophical theories, conforms to the Kabbalistic secrets of the world.”[1]

The Scream by Edvard Munch (1893)

As in the Kabbalah of Isaac Luria, Hegel and the other Romantic philosophers proposed that history was the unfolding of an idea, as God coming to know himself. To Hegel, it is man who becomes God, as Western civilization overcomes “superstition,” that is, man’s idea of God as an entity outside of himself. Thus, history was the evolution of human society towards secularism, or at least a rejection of conventional religion. Ultimately, Nietzsche would finally famously pronounce that “God is Dead.” Nietzsche inspired the notion of “divine madness.” It represents a mind that cracks when it has finally faced the absence of meaning. The experience is aptly portrayed in The Scream, painted by Edvard Munch in 1893, which according to Munch’s biographer, Sue Prideaux, The Scream is “a visualization of Nietzsche’s cry, ‘God is dead, and we have nothing to replace him’.”[2]

The idea also contributed to the development of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. More devastating still, however, was the cynical conclusions Social Darwinism, that were derived the idea of the “survival of the fittest.” Together, these would form the driving concepts behind the rise of fascism. Despite the fact that social Darwinism bears Darwin’s name, it is also linked today with others, notably Herbert Spencer, Thomas Malthus, and Francis Galton. Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus Darwin (1731 – 1802) was a Freemason and a member of the Lunar Society with Francis Galton’s grandfather, Samuel Galton Jr. (1753 - 1832). The Lunar Society included a number of men linked to Freemasonry. The society, or Lunartiks as they liked to call themselves, as they so named because the society would meet during the full moon, began with a group of friends that included Erasmus Darwin, Matthew Boulton, Benjamin Franklin and Joseph Priestley. The nature of the Lunar Society changed significantly with the move to Birmingham in 1765 of the Scottish physician William Small, who had been Professor of Natural Philosophy at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, where he had taught and been a major influence over Thomas Jefferson. Small’s arrival with a letter of introduction to Matthew Boulton from Benjamin Franklin had a galvanizing effect on the circle, which then actively started to attract new members.[3]

Francis Galton (1822 – 1911), founder of eugenics

Eugenics begins with Darwin’s cousin Francis Galton (1822 – 1911). The Darwin and Galton families also boasted Fellows of the Royal Society. Galton coined the term eugenics in 1882, to mean “well born.” Galton thought that the social positions achieved by Britain’s ruling elite were determined by their superior biological disposition.[4] Thomas Malthus’ father was an intimate friend of French philosopher and Freemason, Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Malthus (1766 – 1834), as laid out in his 1798 work, An Essay on the Principle of Population, written in response to William Godwin, describes how unchecked population growth is exponential and would therefore eventually outstrip the food supply whose growth was arithmetical.

An 1871 caricature following publication of The Descent of Man was typical of many showing Darwin with an ape body, identifying him in popular culture as the leading author of evolutionary theory.

The “survival of the fittest” is a term coined by sociologist Herbert Spencer (1820 – 1903), derived from his reading of Malthus. However, Spencer’s major work, Progress: Its Law and Cause (1857) was released two years before the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, and First Principles was printed in 1860. Spencer supported laissez-faire capitalism on the basis of his belief that struggle for survival spurred self-improvement which could be inherited. In The Social Organism (1860), Spencer compares society to a living organism and argues that, just as biological organisms evolve through natural selection, society evolves and increases in complexity through analogous processes.

The publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species helped to create the false impression of a conflict between science and religion, as it brought on a storm of controversy between the scientific establishment and the Church of England, who recognized evolutionism as an attack on what was perceived as the divinely ordained aristocratic social order. Conversely, Darwin’s ideas on evolution were welcomed by liberal theologians and by a new generation of salaried professional scientists, who would later come to form the X Club, who saw his work as a great stride in the struggle for freedom from clerical interference in science.[5]

Thomas Henry Huxley, (1825 –1895), known as “Darwin’s Bulldog,” grandfather of Aldous and Julian Huxley.

This attack was led by Thomas Henry Huxley (1825 – 1895), known as “Darwin’s Bulldog,” grandfather of Aldous and Julian Huxley. Huxley was a long-standing member of the Royal Society, eventually serving as its president. A noted unbeliever, Thomas Huxley used the term “agnostic” to describe his attitude to theism. Huxley applied Darwin’s ideas to humans, using paleontology and comparative anatomy as purported evidence that humans and apes shared a common ancestry. Huxley’s legendary retort, that he would rather be descended from an ape than a man who misused his gifts, came to symbolize the supposed triumph of science over religion.[6]

For about thirty years Huxley was not only evolution’s most influential proponent, but has been described as “the premier advocate of science in the nineteenth century [for] the whole English-speaking world.”[7] On November 3, 1864, the day that lobbying accorded Darwin Britain’s highest scientific honor, the Royal Society’s Copley Medal, Huxley held the first meeting of what became the influential X Club. All nine founding members belonged to the Royal Society, except Herbert Spencer. The X Club were united by a “devotion to science, pure and free, untrammelled by religious dogmas.”[8] According to Ruth Burton, “…they were representatives of expert professional science to the end of the century, becoming leading advisors to government and leading publicists for the benefits of science; they became influential in scientific politics, forming interlocking directorships on the councils of many scientific societies”[9]

Romantic Satanists

Caricature of Joseph Priestley and Illuminatus Thomas Paine inspired by the devil

Joseph Johnson (1738 – 1809)

The Lunar Society gained the support of radical bookseller Joseph Johnson (1738 – 1809). Johnson, who helped shape the thought of his era, held discussions at his famous weekly dinners, whose regular attendees became known as the “Johnson Circle.” In the 1770s and 1780s, Johnson published the popular poetry of Erasmus Darwin. He issued the children’s book on birds produced by the industrialist Samuel Galton and the Lunar Society’s translation of Linnaeus’s System of Vegetables (1783). In 1780, Johnson also issued the first collected political works of Benjamin Franklin in England. Although Johnson is known for publishing Unitarian works, he also published the works of other Dissenters, Anglicans, and Jews. The common thread uniting his disparate religious publications was religious toleration. Johnson is best known for publishing the works of radical thinkers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, Thomas Malthus, Illuminatus Thomas Paine, as well as religious dissenters such as Joseph Priestley, a member Royal Society and of Lord Shelburne’s “Bowood circle,” along with Freemason Richard Price, who was a friend of Franklin and a key supporter of the American Revolution.

Johnson became friends with Priestley and Henry Fuseli (1741 – 1825), two relationships that lasted his entire life and enriched his business. In turn, Priestley trusted Johnson to handle his induction into the Royal Society.[10] Hanging above Johnson’s dinner guests, along with a portrait of Priestley, was Henry Fuseli’s famous The Nightmare, depicting a woman swooning with a demonic incubus crouched on her chest. One of Fuseli’s schoolmates with whom he became close friends was Johann Kaspar Lavater, who had challenged Moses Mendelssohn to convert Christianity.[11]

Along with the portrait of Priestley, The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli (1781) hung above Johnson's dinner guests.

William Godwin (1756 – 1836)

The circle of radical artists around Johnson are known as Romantic Satanists, for their having the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost as a heroic figure who rebelled against “divinely ordained” authority.[12] They were inspired by Milton’s famous line were Satan declares, “Better to reign in Hell, than to serve in Heav’n.” This attitude was found in Johnson’s friend, artist Henry Fuseli, who portrayed the fallen angel as a classical hero. In 1799, Fuseli exhibited own “Milton Gallery,” a series of 47 paintings from themes from Paradise Lost, with a view to forming a Milton gallery comparable to Boydell’s Shakespeare gallery. William Godwin (1756 – 1836), wrote in Enquiry into Political Justice (1793), where Milton’s Satan persists in his struggle against God even after his fall, and “bore his torments with fortitude, because he disdained to be subdued by despotic power.” Godwin, who is regarded as one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of philosophical anarchism. Godwin was married to Fuseli’s former lover, the philosopher and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797), best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy.

Fuseli’s style had a considerable influence on many younger British artists, including William Blake (1757 – 1827), who was employed by Johnson. Largely unrecognized in his own lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and arts of the Romantic Age, along with William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor. Blake frequented Swedenborg’s New Jerusalem Society, which was influenced by the Kabbalistic sexual practice of Count Zinzendorf. While there is no record of Blake belonging to Freemasonry, he has been universally regarded in the occult as one of its great sages. However, Blake’s biographer Peter Ackroyd noted that according to the lists of grandmasters of the Druid Order, Blake was a grandmaster from 1799 until 1827. Of druidism Blake believed that, “The Egyptian Hieroglyphs, the Greek and the Roman Mythology, and the Modern Freemasonry being the last remnants of it. The honorable Emanuel Swedenborg is the wonderful Restorer of this long lost Secret.”[13] One of his most well-recognized paintings is that of the Ancient of Days of the Kabbalah, holding the Masonic symbol of a compass over a darker void below.

William Blake’s Satan Exulting over Eve, illustration of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Johnson introduced Blake to the radical circle of Wollstonecraft, Godwin and Thomas Paine. In the 1790s, Johnson aligned himself with the supporters of the French Revolution, promoting the translation of the works such as Condorcet’s Outlines of an Historical View of the Progress of the Human Mind (1795). However, many British reformers became disillusioned with the Reign of Terror, and those who those radicals who still supported the French revolution were viewed with increasing suspicion. Responding in part to a sermon defending the French Revolution given by Price entitled A Discourse on the Love of Our Country (1789), Edmund Burke published the counterrevolutionary Reflections on the Revolution in France, where he tied natural philosophers, and specifically Priestley, to the French Revolution. Because he had supported the American revolution against Britain, reactions against Burke’s views erupted in a pamphlet war, now referred to as the “Revolution Controversy.” Radicals such as William Godwin, Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft argued for republicanism, agrarian socialism and anarchism.

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797)

Through Johnson, Wollstonecraft was introduced to the circle of Richard Price. Wollstonecraft had been much inspired by Price’s sermons which influenced A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), her response to Burke’s denunciation of her mentor. Wollstonecraft, according to Adriana Craciun, “was among the first in a line of romantic outcasts who modeled themselves on the fallen hero of Paradise Lost.”[14] In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, explains Craciun, it was the Adversary himself with whom Wollstonecraft identifies. Seeing through Milton’s domestic paradise: “The domestic trifles of the day have afforded matters for cheerful converse,” she writes regarding contemporary perceptions of women’s domesticity. “Similar feelings has Milton’s pleasing picture of paradisiacal happiness ever raised in my mind,” Wollstonecraft adds, “yet, instead of envying the lovely pair [Adam and Eve], I have with conscious dignity, or Satanic pride, turned to hell for sublimer objects.”[15]

Wollstonecraft left for Paris in December 1792, where she associated with the Girondins. After two failed affairs with artist Henry Fuseli and Gilbert Imlay, Wollstonecraft married William Godwin. After Wollstonecraft’s death, Godwin published a Memoir (1798) of her life, revealing her promiscuous lifestyle, which destroyed her reputation for almost a century. The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine, a conservative British political periodical, concluded that “the moral sentiments and moral conduct of Mrs. Wollstonecroft [sic], resulting from their principles and theories, exemplify and illustrate JACOBIN MORALITY” and warns parents against rearing their children according to her advice.[16] Such accusations, explains Chandos Michael Brown, in a time of widespread suspicion of the subversive activities of the Jacobins, would have regarded Wollstoncroft as a female Illuminati.[17] Brown refers to the long-standing interest of the Illuminati in creating a Minerval school for girls. In 1782, Illuminatus “Minos” (Baron von Ditfurth), wrote: “Philo (Knigge] and I have long conversed on this subject. We cannot improve the world without improving women, who have such a mighty influence on the men.”[18] Minos added:

There is no way of influencing men so powerfully as by means of the women. These should therefore be our chief study; we should insinuate ourselves into their good opinion, give them hints of emancipation from the tyranny of public opinion, and of standing up for themselves; it will be an immense relief to their enslaved minds to be freed from any one bond of restraint, and it will fire them the more, and cause them to work for us with zeal, without knowing that they do so. For they will only be indulging their own desire of personal admiration.[19]

Paine argued in Rights of Man that popular political revolution was permissible when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people. On January 31, 1791, he gave the manuscript to publisher Johnson, but a visit by government agents dissuaded him from publishing the work. Paine gave the book to publisher J. S. Jordan, then went to Paris, on the advice of William Blake. Paine charged three of his good friends, William Godwin, Thomas Brand Hollis, and Thomas Holcroft, with handling the details of the publication. The book appeared in 1791, and sold nearly a million copies. It was “eagerly read by reformers, Protestant dissenters, democrats, London craftsmen, and the skilled factory-hands of the new industrial north.”[20]

When a writ for his arrest issued in early 1792, Paine fled to France, where he was quickly elected to the French National Convention. In December 1793, Paine was arrested and was taken to Luxembourg Prison in Paris, and was to be executed by the guillotine, but was released the following year James Monroe, a future President of the United States, exercised his diplomatic connections. It was while in prison that Paine continued to work on The Age of Reason (1793 – 1794). More of an influence on Paine than David Hume was Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-politicus (1678). Although Paine promoted natural religion and argues for the existence of a creator-God, he advocated reason in the place of revelation, leading him to reject miracles and to view the Bible as an ordinary piece of literature, rather than a divinely-inspired text. “All national institutions of churches,” wrote Paine, “whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.”[21] Paine wrote that once one relinquishes the idea that Moses was the author of Genesis, “The story of Eve and the serpent, and of Noah and his ark, drops to a level with the Arabian tales, without the merit of being entertaining.”[22]

The conservative government, headed by William Pitt (1756 – 1806), responded to the increasing radicalization by prosecuting several reformers for seditious libel and treason in the famous 1794 Treason Trials. Following the trials and an attack on George III, conservatives were successful in passing the Seditious Meetings Act and the Treasonable Practices Act in 1795, which permitted indictments against radicals for “libelous and seditious” statements. In 1799, Johnson was indicted for publishing a pamphlet by the Unitarian minister Gilbert Wakefield. After spending six months in prison, Johnson published fewer radical works, though he remained successful by publishing the collected works of authors such as William Shakespeare.

Blake produced the illustrations for an 1808 edition of Paradise Lost. Blake famously wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it.” Blake’s Marriage of Heavan and Hell, explain Per Faxneld and Jesper Aa. Petersen, could be considered the first “satanic” Bible in history.[23] Through the voice of the Devil, Blake parodies and attacks the theology of Emanuel Swedenborg, the cosmology and ethics of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and biblical history and morality as constructed by the “Angels” of the established church and state. The Bible and other religious texts, Blake says, have been responsible for a lot of the misinformation. Although Hell is perceived as full of torment, it actually is a place where free-thinkers revel in the full experience of existence. While he was touring around, Blake says he collected some of the Proverbs of Hell, one of which famously stated: “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” The book ends with the Song of Liberty, a prose poem where Blake uses apocalyptic imagery to incite his readers to embrace the coming revolution.

Frankenstein

John Boles and Boris Karloff in James Whale's 1931 film adaptation of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein.

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 – 1822)

William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft were the parents of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797 – 1851), author of Frankenstein. Mary’s husband Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 – 1822), who wrote Prometheus Unbound, equating the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost with Prometheus, the Greek mythological figure Prometheus, who defies the gods and gives fire to humanity, for which he is subjected to eternal punishment and suffering at the hands of Zeus. Percy is regarded by critics as amongst the finest lyric poets in the English language. Percy was expelled from Oxford after he published his Necessity of Atheism in 1811. Shelley was inspired by Spinoza to write his essay “The Necessity of Atheism,” which was circulated to all the heads of Oxford colleges at the University, where it caused great controversy. Shelley quotes Spinoza in his note in Canto VII of Queen Mab, published two years later and based on the essay. There, Shelley qualifies his definition of atheism in relation to Spinoza’s pantheism:

There Is No God. This negation must be understood solely to affect a creative Deity. The hypothesis of a pervading Spirit co-eternal with the universe remains unshaken.[24]

In his authoritative biography on Shelley, James Bieris notes that while Shelley was at Eton Shelley spent much of his leisure time reading on occult science, and spent his money on books on witchcraft and magic and on scientific instruments and materials. Also at Eton, Shelley was reported to have tried to “raise a ghost,” taking a proscribed skull which he drank from three time, fearing that the devil was following him, but no ghost appeared.[25] In his youth, Shelley had fallen under the influence of Dr. James Lind, a member of the Lunar Society and considered the modern-day Paracelsus. In fact, among Shelley’s favorite topics for research was Paracelsus, in addition to magic and alchemy. Among Percy Shelley’s best-known works are Prometheus Unbound, and The Rosicrucian, A Romance, a Gothic horror novel where the main character Wolfstein, a solitary wanderer, encounters Ginotti, an alchemist of the Rosicrucian or Rose Cross Order who seeks to impart the secret of immortality.

Shelley read the anti-religious works of Lucretius and the Illuminatus Condorcet.[26] Percy Shelley read Barruel’s Memoirs “again and again… [being] particularly taken with the conspiratorial account of the Illuminati.”[27] At Oxford, Shelley became friends with Thomas Jefferson Hogg, his future biographer, who reported, “He used to read aloud to me with rapturous enthusiasm the wondrous tales of German Illuminati, and he was disappointed, sometimes even displeased, when I expressed doubt or disbelief.”[28] On March 2, 1811, Shelley, who thought of creating his own “association” along similar lines, sent a letter to the editor of the Examiner in which he expressed his desire of “applying the machinery of Illuminism.”[29] Likewise, writes Mary Shelley’s biographer, Miranda Seymour, “Sitting on the shores of Lake Lucerne, Mary had been introduced to one of Shelley’s favorite books, the Abbé Barruel’s Memoirs… Here, Barruel traced the birth of ‘the monster called Jacobin’ to the secret society of the Illuminati at Ingolstadt. Ingolstadt is where Mary decided to send Victor Frankenstein to university; Ingolstadt is where he animates his creature…”[30]

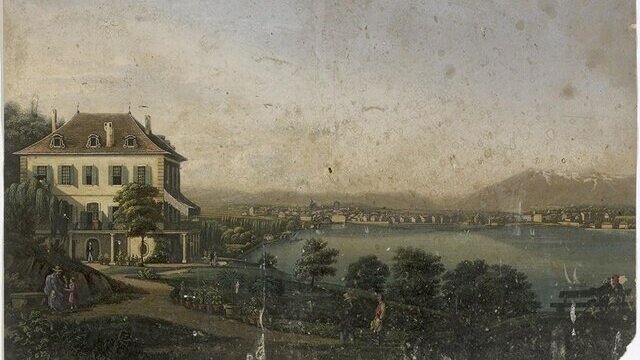

The Villa Diodati as it may have looked in Shelley's time.

Lord Byron (1788 – 1824) in Albanian dress by Thomas Phillips, 1813.

English Romantic poetry is believed to have reached its zenith in the works of Keats, Shelley and Lord Byron (1788 – 1824).[31] Mary and Percy Shelley were also closely associated Byron, who is described as the most flamboyant and notorious of the leading Romantics. Byron was celebrated during his lifetime for aristocratic excesses, including huge debts, numerous love affairs with both sexes, rumors of a scandalous incestuous liaison with his half-sister, and self-imposed exile. Byron travelled all over Europe, especially in Italy where he lived for seven years and became a member of the Carbonari. He later joined the Greek War of Independence fighting the Ottoman Empire, for which Greeks revere him as a national hero.[32] Influenced by Milton’s Paradise Lost, Byron wrote Cain: A Mystery in 1821, provoking an uproar because the play dramatized the story of Cain and Abel from the point of view of Cain, who is inspired by Lucifer to protest against God.

In 1816, at the Villa Diodati, a house Byron rented by Lake Geneva in Switzerland, Mary, Percy and John Polidori (1795 – 1821) decided to have a competition to see who could write the best horror story, which resulted in Mary’s Frankenstein. Polidori was an English writer and physician, known for his associations with the Romantic movement and credited by some as the creator of the vampire genre of fantasy fiction. His most successful work was the short story The Vampyre (1819), produced by the same writing contest, and the first published modern vampire story.

The fable of the alchemically-created homunculus, which was related to the Jewish legend of the golem, may have been central in Shelley’s novel Frankenstein. Professor Radu Florescu suggests that Johann Conrad Dippel, an alchemist born in Castle Frankenstein, might have been the inspiration for Victor Frankenstein. Victor Frankenstein, the protagonist of Mary’s novel, admits to having been inspired by Agrippa, Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus, all magicians and among the most celebrated figures in Western occult tradition. Victor begins his account by announcing, “I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.”

Shelley was inspired by Frankenstein Castle in Odenwald, Germany, where two centuries before an alchemist was engaged in experiments.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797 – 1851), author of Frankenstein.

Mary Shelley was inspired by Frankenstein Castle, where two centuries before an alchemist was engaged in experiments. Frankenstein Castle is on a hilltop in the Odenwald overlooking the city of Darmstadt in Germany. The castle gained international attention when the SyFy TV-Show Ghost Hunters International produced an entire episode about the castle in 2008, after which the team became convinced that there was some sort of paranormal activity going on. Frankenstein Castle is associated with numerous occult legends, including that of a knight named Lord Georg who saved local villagers from a dragon, and a fountain of youth where in the first full-moon night after Walpurgis Night old women from the nearby villages had to undergo tests of courage. The one who succeeded was returned to the age she had been in the night of her wedding. On Mount Ilbes, in the forest behind Frankenstein Castle, compasses do not work properly due to magnetic stone formations. Legend has it that Mount Ilbes is the second most important meeting place for witches in Germany after Mount Brocken in the Harz. In the late seventeenth century, Johann Conrad Dippel stayed at Frankenstein, where he was rumored to have practiced alchemical experiments on corpses that he exhumed, and that a local cleric warned his parish that Dippel had created a monster that was brought to life by a bolt of lightning. Local people still claim this to have actually happened and that this tale was related to Shelley’s stepmother by the Grimm brothers, the German fairy-tale writers.[33]

Hail Santa

Illustrated scene from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens (1812 –1870)

Mary Shelley was on friendly terms with John Howard Payne (1791 – 1852), an American actor and poet who enjoyed nearly two decades of a theatrical career and success in London. Payne is today most remembered as the creator of “Home! Sweet Home!.” After his return to the United States in 1832, Payne spent time with the Cherokee Indians in the Southeast and published a theory that suggested their origin as one of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Payne’s belief was shared by other figures of the early American period, including Benjamin Franklin.[34] Payne had become infatuated with Shelley, but lost interest when he realized she hoped only to use him to attract the attention of his friend, American short-story writer Washington Irving (1783 – 1859).[35] Irving was one of the first American writers to earn fame in Europe, and thus encouraged other American authors such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Herman Melville and Edgar Allan Poe. Irving was also admired by number of British writers, including Lord Byron, Thomas Campbell, Charles Dickens, Mary Shelley, Francis Jeffrey and Walter Scott, who became a lifelong personal friend.

Charles Dickens’ 1843 novel A Christmas Carol was highly influential, and has been credited both with reviving interest in Christmas in England and with shaping the themes associated with it.[36] Christmas celebrations were first revived by Francis Bacon at the Inns of Court, where they were presided over by the Lord of Misrule, borrowed directly from the ancient Saturnalia and its worship of Saturn, or Satan.[37] Although the month and date of Jesus’ birth are unknown, the church in the early fourth century fixed the date as December 25, which corresponds to the date of the winter solstice on the Roman calendar, in imitation of the nativity of Sol Invictus, who was also worshipped as Mithras. Following the Protestant Reformation, many of the new denominations continued to celebrate the holiday. In 1629, the John Milton penned On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity, a poem that has since been read by many during Christmastide.[38] However, when the Puritans took control of government in the mid-1640s they made concerted efforts to abolish Christmas and to outlaw its traditional customs. In 1647, parliament passed an Ordinance for Abolishing of Festivals which formally abolished Christmas in its entirety, along with the other traditional church festivals of Easter and Whitsun.

Washington Irving (1783 – 1859)

Following the Restoration in 1660, most traditional Christmas celebrations were revived, and during the Victorian period, they enjoyed a significant revival, including the figure of Father Christmas. In the early nineteenth century, Christmas festivities became widespread with the rise of the Oxford Movement in the Church of England which emphasized the centrality of Christmas in Christianity, along with Irving, Dickens, and other authors emphasizing children, gift-giving, and Santa Claus or Father Christmas.[39] In the 1820s, interest in Christmas was revived in America by several short stories by Irving which appeared in his The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. and “Old Christmas.” Irving’s stories depicted English Christmas festivities he experienced while staying in Aston Hall in Birmingham, that had largely been abandoned. As a format for his stories, Irving used the tract Vindication of Christmas (1652) of Old English Christmas traditions, that he had transcribed into his journal.[40]

Irving’s friend, Clement Clarke Moore (1779 – 1863), was the author of A Visit from St. Nicholas, more commonly known as ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas, a poem first published anonymously in 1823, through which modern ideas of Santa Claus were popularized. “St. Nick” is described as being “chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf” covered in soot, with “a little round belly,” riding a “miniature sleigh” pulled by “tiny reindeer” named: Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder and Blixem, which came from the old Dutch words for thunder and lightning, which were later changed to the more German sounding Donner and Blitzen. Of the numerous mythological connections between Santa and Satan, Jeffrey Burton Russell explains in The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History:

The Devil comes from the north, domain of darkness and punishing cold. Curious connections exist between Satan and Santa Claus (Saint Nicholas). The Devil lives in the far north and drives reindeer; he wears a suit of red fur; he goes down chimneys in the guise of Black Jack or the Black Man covered in soot; as Black Peter he carries a large sack into which he pops sins or sinners (including naughty children); he carries a stick or cane to thrash the guilty (now he merely brings candy canes); he flies through the air with the help of strange animals; food and wine are left out for him as a bribe to secure his favors. The Devil's nickname (!) “Old Nick” derives directly from Saint Nicholas. Nicholas was often associated with fertility cults, hence with fruit, nuts, and fruitcake, his characteristic gifts.[41]

Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. also included the short stories for which he is best known, “Rip Van Winkle” (1819) and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820), which was especially during Halloween because of a character known as the Headless Horseman believed to be a Hessian soldier who was decapitated by a cannonball in battle. In 1824, Irving published the collection of essays Tales of a Traveller, including the short story “The Devil and Tom Walker,” a story very similar to the German legend of Faust. The story first recounts the legend of the pirate William Kidd, who is rumored to have buried a large treasure in a forest in colonial Massachusetts. Kidd made a deal with the devil, referred to as “Old Scratch” and “the Black Man” in the story, to protect his money.

Conflict Thesis

Andrew Dickson White (1832 – 1918), wearing Skull and Bones pin

In 1826, American Minister to Spain Alexander Hill Everett (1792 – 1847), a member of the American Philosophical Society, inviting Irving to join him in Madrid, where he was given full access to the American consul’s massive library of Spanish history. As a result, Irving wrote a fictional biography titled A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, published in 1828. During his research, Irving worked closely with Alexander von Humboldt (1769 – 1859), who had been admitted to the intellectual leaders of Weimar Classicism, which included Goethe and Schiller. Humboldt had recently returned from his own trip to South American, and was able to provide advanced knowledge of the geography and science of the continent and together they charted the route and first landing of Columbus in the Americas.[42]

Irving’s history helped contribute to the Flat Earth Myth. Mistaken by many for a scholarly work, the book produced a fictional account of the meetings of a commission established by the Spanish crown to examine Columbus’ proposals, including the unlikely story that the more ignorant and bigoted members on the commission had raised scriptural objections to Columbus’ assertions that the Earth was spherical. In reality, the earliest documentation of the idea of a spherical Earth comes from the ancient Greece in the fifth century BC, and the belief was widespread after Eratosthenes (c. 276 – c. 195/194 BC) calculated the circumference of Earth around 240 BC. Early Islamic scholars recognized Earth’s sphericity, leading Muslim mathematicians to develop spherical trigonometry, and a belief in a flat Earth among educated Europeans was almost nonexistent from the Late Middle Ages onward. According to Stephen Jay Gould, “there never was a period of 'flat Earth darkness' among scholars, regardless of how the public at large may have conceptualized our planet both then and now. Greek knowledge of sphericity never faded, and all major medieval scholars accepted the Earth’s roundness as an established fact of cosmology.”[43]

According to Historian Jeffrey Burton Russell, the flat-Earth error flourished most between 1870 and 1920, and had to do with the ideological setting created by struggles over biological evolution, and ascribes popularization of the myth to histories by Washington Irving, as well as John William Draper (1811 – 1882) and Andrew Dickson White (1832 – 1918), the most influential exponents of the conflict thesis between religion and science. At Yale, White became a member of Skull and Bones, along with his close friend and classmate Daniel Coit Gilman (1831 – 1908), who would later serve as the first president of Johns Hopkins University and founding president of the Carnegie Institution.[44] Gilman was also co-founder of the Russell Trust Association, which administers the Skull and Bones’ business affairs. Gilman was also a member to the American Philosophical Society.[45]

John William Draper (1811 – 1882)

Draper had been the speaker in the British Association meeting of 1860 which led to the famous confrontation between Bishop Samuel Wilberforce—the son of William Wilberforce—and Thomas Henry Huxley over Darwinism, following which in America “the religious controversy over biological evolution reached its most critical stages in the late 1870s.”[46] Draper wrote a History of the Conflict between Religion and Science in 1874, repeating the assertion that the early Church fathers believed the Earth was flat as evidence of the hostility of the Church to the advancement of science. The story was repeated by White in his 1876 The Warfare of Science and elaborated twenty years later in his two-volume History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom, which exaggerated the number and significance of believers in the flat Earth during medieval times to support his claim of warfare between theology and scientific progress.

Transcendentalism

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1882), father of American Transcendentalism

John Ruskin (1819 – 1900)

The children of Polidori’s sister Frances and Gabriele Rossetti (1783 – 1854), an Italian poet and a political exile, included Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882) and William Michael Rossetti (1829 – 1919), who were founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of English painters, poets, and critics, established in 1848 along with William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais. The Pre-Raphaelite’s intention was to reform art by rejecting what it considered the mechanistic approach first adopted by Mannerist artists who succeeded Raphael and Michelangelo. Its members believed the Classical poses and elegant compositions of Raphael in particular had been a corrupting influence on the academic teaching of art, hence the name “Pre-Raphaelite.”

The Pre-Raphaelite’s were championed by John Ruskin (1819 – 1900), who was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era. From the 1850s, the Pre-Raphaelites who were influenced by Ruskin’s ideas, and provided the antecedents for the development of modernism. Ruskin knew and respected Darwin personally, though he also attacked aspects of Darwinian theory. Ruskin’s gravestone at Coniston where he is buried betrays his occult beliefs, featuring Celtic triskele symbols, a swastika within a Maltese Cross, and St. George slaying a dragon.

Dante and his circle were deeply interested in Arthurian legends. In the late 1850’s, Dante painted scenes from Malory’s Morte D’Arthur in fresco in the Oxford Union Debating Society hall, and completed three Arthurian illustrations for the Moxon edition of Tennyson. In 1856, William Morris commissioned Dante to paint The Damsel of the Sanct Grael, which reinforced the association of the grail with Christ’s blood. In Dante’s painting, the grail maiden holds the devices of the Eucharist in her left hand: the golden chalice brimming with blood and a basket of bread over which a folded white cloth is draped. Her right hand is raised in a gesture of benediction. Over her head hovers the white dove of the Holy Spirit with outstretched wings and bearing a smoke-emitting censer in its mouth.

Emerson was the first person to join the association the Free Religious Association (FRA). The FRA was formed in 1867 in part by American minister and Transcendentalist author influenced by Emerson, David Atwood Wasson, with Lucretia Mott, and Reverend William J. Potter, to be, in Potter's words, a “spiritual anti-slavery society” to “emancipate religion from the dogmatic traditions it had been previously bound to.”[54] The FRA was opposed not only to organized religion, but also to any supernaturalism in an attempt to affirm the supremacy of individual conscience and individual reason. The FRA carried a Masonic message of the perfectibility of humanity, democratic faith in the worth of each individual, the importance of natural rights and the affirmation of the efficacy of reason. The first public assembly was held in 1867 with an audience ranging from Progressive Quakers, liberal Jews, radical Unitarians, Universalists, agnostics, Spiritualists, and scientific theists.

Charles Darwin was a member of the FRA and staunch supporter of his friend Francis Abbot (1836 – 1903), FRA co-founder and editor of its radical weekly journal, The Index. In the December 23, 1871, issue Darwin shared a rare glimpse of his unitarian religious beliefs. Responding to Abbot’s manifesto Truths for the Times, Darwin wrote that he admired Abbot’s “truths” “from my inmost heart; and I agree to almost every word,” adding, “The points on which I doubtfully differ are unimportant.” Abbot had proclaimed religion to be man’s effort to perfect himself. He called for the “extinction of faith in the Christian Confession” and its replacement with “Free Religion” which he defined as “faith in Man as a progressive being.” Instead of “the Church,” Abbot looked forward to “the coming Republic of the World, or Commonwealth of Man, the universal conscience and reason of mankind being its supreme organic law or constitution.”[55]

The FRA included numerous American Jewish Reform rabbis, including Isaac Meyer Wise, Max Lilienthal the editor of The Israelite, Moritz Ellinger, Aaron Guinzburg, Raphael Lasker, S. H. Sonneschein, I. S. Nathans, Henry Gersoni, Judah Wechsler, Felix Adler, Bernhard Felsenthal, Edward Lauterbach, Solomon Schindler, Emil G. Hirsch and eventually the Sabbatean Stephen Samuel Wise (1874 – 1949), founder of the of the national Federation of American Zionists (FAZ), forerunner of the Zionist Organization of America.[56] The proponents of Reform Judaism had consistently claimed since the early nineteenth-century to aim to reconcile Jewish religion with advancements scientific thought, and the science of evolution was of particular interest. In a series of twelve sermons published as The Cosmic God (1876), Rabbi Wise offered an alternative theistic account of Darwinism. Other Reform rabbis who were more sympathetic to Darwinian included Kaufmann Kohler, Emil G. Hirsch, and Joseph Krauskopf. Hirsch, for example, wrote:

In notes clearer than ever were entoned by human tongue does the philosophy of evolution confirm essential verity of Judaism’s insistent protest and proclamation that God is one. This theory reads unity in all that is and has been. Stars and stones, planets and pebbles, sun and sod, rock and river, leaf and lichen are spun of the same thread. Thus the universe is one soul, One spelled large. If throughout all visible form one energy is manifest and in all material shape one substance is apparent, the conclusion is all the better assured which holds this essentially one world of life to be the thought of one all embracing and all underlying creative directive mind... I, for my part, believe to be justified in my assurance that Judaism rightly apprehended posits God not, as often it is said to do, as an absolutely transcendental One. Our God is the soul of the Universe... Spinozism and Judaism are by no means at opposite poles.[57]

Gabriele Rossetti (1783 – 1854)

The Pre-Raphaelite’s were championed by John Ruskin (1819 – 1900) was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era. From the 1850s, Ruskin championed the Pre-Raphaelites who were influenced by his ideas, and who provided the antecedents for the development of modernism. Ruskin knew and respected Darwin personally, though he also attacked aspects of Darwinian theory. Ruskin’s gravestone at Coniston where he is buried betrays his occult beliefs, featuring Celtic triskele symbols, a swastika within a Maltese Cross, and St. George slaying a dragon.

The Damsel of the Sanct Grael by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1874)

William Morris and C. R. Ashbee (the Guild of Handicraft) were keen disciples, and through them Ruskin’s legacy can be traced in the arts and crafts movement. Dante had a relationship with the model Jane Morris, who married William Morris, and for both of whom she served as muse. Eliza Doolittle in Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion (1914) and the later film My Fair Lady was based on Jane Morris. Dante’s work also influenced the European Symbolists, a late nineteenth-century art movement of French, Russian and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts. In literature, the style had its beginnings with the publication Les Fleurs du mal (“The Flowers of Evil,” 1857) by Charles Baudelaire, which signaled the birth of modernism in literature.[47]

Dante and his circle were deeply interested in Arthurian legends. In the late 1850’s, Dante painted scenes from Malory’s Morte D’Arthur in fresco in the Oxford Union Debating Society hall, and completed three Arthurian illustrations for the Moxon edition of Tennyson. In 1856, William Morris commissioned Dante to paint The Damsel of the Sanct Grael, which reinforced the association of the grail with Christ’s blood. In Dante’s painting, the grail maiden holds the devices of the Eucharist in her left hand: the golden chalice brimming with blood and a basket of bread over which a folded white cloth is draped. Her right hand is raised in a gesture of benediction. Over her head hovers the white dove of the Holy Spirit with outstretched wings and bearing a smoke-emitting censer in its mouth.

Walt Whitman (1819 – 1892)

In 1868, Poems of Walt Whitman was published in England thanks to the influence of William Michael Rossetti. Whitman (1819 – 1892) is considered one of America’s most influential poets. Whitman’s work was very controversial even in its time, particularly his poetry collection Leaves of Grass, which was described as obscene for its overt sexuality. Though biographers continue to debate his sexuality, he is usually described as either homosexual or bisexual in his feelings and attractions. Oscar Wilde met Whitman in America in 1882 and wrote that there was “no doubt” about Whitman’s sexual orientation: “I have the kiss of Walt Whitman still on my lips,” he boasted.[48] According to Maurice Bucke, Whitman was among the many sages he believed achieved “cosmic consciousness,” in addition to Jesus, Swedenborg and William Blake, but that Whitman was “the climax of religious evolution and the harbinger of humanity’s future.”[49]

Whitman is a prominent exponent of the Transcendentalist movement. In 1855, when Whitman sent a copy of Leaves of Grass to Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1882) for his opinion, Emerson's approval helped the first edition generate significant interest.[50] Influenced by Swedenborg, Blake and the Vedanta, Emerson was the father of American Transcendentalism, a religious and philosophical movement that developed during the late 1820s and 30s as a protest against conventional spirituality and the Unitarian doctrine taught at Harvard Divinity School. Transcendentalism begins with Emerson’s 1836 essay Nature, which was heavily influenced by Swedenborg’s theory of “correspondences” and the idea that all individual souls were part of a world soul.[51] The movement directly influenced New Thought, a spiritual movement following the teachings of Phineas Quimby (1802 – 1866). During the late nineteenth century Quimby’s metaphysical healing practices mingled with the “Mental Science” of Warren Felt Evans, a Swedenborgian minister. Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, has been cited as having used Quimby as inspiration for theology.

Madame Germaine de Staël, a friend of Moses Mendelssohn’s daughter Dorothea, wife of Friedrich Schlegel, was frequently quoted by Emerson and she is credited with introducing him to recent German thought. Herman Melville, author of Moby Dick, considered de Staël among the greatest women of the century and Margaret Fuller consciously adopted de Staël as her role model.[52] In London, de Staël met Lord Byron and William Wilberforce the abolitionist. Byron, at that time in debt, left London and frequently visited de Staël in Coppet in 1815, where she headed the Coppet Circle. For Byron, de Staël was Europe’s greatest living writer, but “with her pen behind her ears and her mouth full of ink.”[53]

Henry David Thoreau (1817 – 1862)

The children of Polidori’s sister Frances and Gabriele Rossetti (1783 – 1854), an Italian poet and a political exile, included Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882) and William Michael Rossetti (1829 – 1919), who were founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of English painters, poets, and critics, established in 1848 along with William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais. The Pre-Raphaelite’s intention was to reform art by rejecting what it considered the mechanistic approach first adopted by Mannerist artists who succeeded Raphael and Michelangelo. Its members believed the Classical poses and elegant compositions of Raphael in particular had been a corrupting influence on the academic teaching of art, hence the name “Pre-Raphaelite.”

The Pre-Raphaelite’s were championed by John Ruskin (1819 – 1900) was the leading English art critic of the Victorian era. From the 1850s, Ruskin championed the Pre-Raphaelites who were influenced by his ideas, and who provided the antecedents for the development of modernism. Ruskin knew and respected Darwin personally, though he also attacked aspects of Darwinian theory. Ruskin’s gravestone at Coniston where he is buried betrays his occult beliefs, featuring Celtic triskele symbols, a swastika within a Maltese Cross, and St. George slaying a dragon.

Dante and his circle were deeply interested in Arthurian legends. In the late 1850’s, Dante painted scenes from Malory’s Morte D’Arthur in fresco in the Oxford Union Debating Society hall, and completed three Arthurian illustrations for the Moxon edition of Tennyson. In 1856, William Morris commissioned Dante to paint The Damsel of the Sanct Grael, which reinforced the association of the grail with Christ’s blood. In Dante’s painting, the grail maiden holds the devices of the Eucharist in her left hand: the golden chalice brimming with blood and a basket of bread over which a folded white cloth is draped. Her right hand is raised in a gesture of benediction. Over her head hovers the white dove of the Holy Spirit with outstretched wings and bearing a smoke-emitting censer in its mouth.

Emerson was the first person to join the association the Free Religious Association (FRA). The FRA was formed in 1867 in part by American minister and Transcendentalist author influenced by Emerson, David Atwood Wasson, with Lucretia Mott, and Reverend William J. Potter, to be, in Potter's words, a “spiritual anti-slavery society” to “emancipate religion from the dogmatic traditions it had been previously bound to.”[53] The FRA was opposed not only to organized religion, but also to any supernaturalism in an attempt to affirm the supremacy of individual conscience and individual reason. The FRA carried a Masonic message of the perfectibility of humanity, democratic faith in the worth of each individual, the importance of natural rights and the affirmation of the efficacy of reason. The first public assembly was held in 1867 with an audience ranging from Progressive Quakers, liberal Jews, radical Unitarians, Universalists, agnostics, Spiritualists, and scientific theists.

Charles Darwin was a member of the FRA and staunch supporter of his friend Francis Abbot (1836 – 1903), FRA co-founder and editor of its radical weekly journal, The Index. In the December 23, 1871, issue Darwin shared a rare glimpse of his unitarian religious beliefs. Responding to Abbot’s manifesto Truths for the Times, Darwin wrote that he admired Abbot’s “truths” “from my inmost heart; and I agree to almost every word,” adding, “The points on which I doubtfully differ are unimportant.” Abbot had proclaimed religion to be man’s effort to perfect himself. He called for the “extinction of faith in the Christian Confession” and its replacement with “Free Religion” which he defined as “faith in Man as a progressive being.” Instead of “the Church,” Abbot looked forward to “the coming Republic of the World, or Commonwealth of Man, the universal conscience and reason of mankind being its supreme organic law or constitution.”[54]

The FRA included numerous American Jewish Reform rabbis, including Isaac Meyer Wise, Max Lilienthal the editor of The Israelite, Moritz Ellinger, Aaron Guinzburg, Raphael Lasker, S. H. Sonneschein, I. S. Nathans, Henry Gersoni, Judah Wechsler, Felix Adler, Bernhard Felsenthal, Edward Lauterbach, Solomon Schindler, Emil G. Hirsch and eventually the Sabbatean Stephen Samuel Wise (1874 – 1949), founder of the of the national Federation of American Zionists (FAZ), forerunner of the Zionist Organization of America.[55] The proponents of Reform Judaism had consistently claimed since the early nineteenth-century to aim to reconcile Jewish religion with advancements scientific thought, and the science of evolution was of particular interest. In a series of twelve sermons published as The Cosmic God (1876), Rabbi Wise offered an alternative theistic account of Darwinism. Other Reform rabbis who were more sympathetic to Darwinian included Kaufmann Kohler, Emil G. Hirsch, and Joseph Krauskopf. Hirsch, for example, wrote:

In notes clearer than ever were entoned by human tongue does the philosophy of evolution confirm essential verity of Judaism’s insistent protest and proclamation that God is one. This theory reads unity in all that is and has been. Stars and stones, planets and pebbles, sun and sod, rock and river, leaf and lichen are spun of the same thread. Thus the universe is one soul, One spelled large. If throughout all visible form one energy is manifest and in all material shape one substance is apparent, the conclusion is all the better assured which holds this essentially one world of life to be the thought of one all embracing and all underlying creative directive mind... I, for my part, believe to be justified in my assurance that Judaism rightly apprehended posits God not, as often it is said to do, as an absolutely transcendental One. Our God is the soul of the Universe... Spinozism and Judaism are by no means at opposite poles.[56]

Margaret Fuller (1810 – 1850), friend of Guisseppe Mazzini

Emerson is also well known as a mentor and friend of fellow Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau (1817 – 1862). Thoreau and Whitman were also associated with the Democratic Review, which was responsible for promoting the concept of Manifest Destiny, and which was dominated by members Young America, who were modelled on Mazzini’s Young Italy. Fellow contributor Nathaniel Hawthorne and his wife Sophia, the goddaughter of John L. O’Sullivan, were both associated with the transcendentalist movement. The couple were also close friends with American journalist Margaret Fuller, who was also associated with the Democratic Review and influenced by Swedenborg.[58] Thomas Carlyle and his wife, Jane, had introduced Fuller to Mazzini, with whom she became a close friend.[59] Emerson was so impressed with Fuller that he invited her to join the Transcendental Club and to edit its literary review, The Dial. Fuller was also an inspiration to Whitman.

Go Ask Alice

Ruskin betrayed pedophile tendencies, showing an unusual interest in young girls. In a letter to his physician John Simon in 1886, Ruskin wrote, “I like my girls from ten to sixteen—allowing of 17 or 18 as long as they’re not in love with anybody but me.—I’ve got some darlings of 8—12—14—just now, and my Pigwiggina here—12—who fetches my wood and is learning to play my bells.”[60] Ruskin fell in love with Rose La Touche, the daughter of a wealthy Irish family, when she was only ten and he 39. He proposed to her on her eighteenth birthday, but she ultimately rejected him. When she died at the age of 27, these events plunged Ruskin into despair and led to increasingly severe bouts of mental illness involving a number of breakdowns and delirious visions, a condition that seems to have plagued much of the bohemian generation that succeeded him.

Ruskin was also a close friend of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (1832 – 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland. Dodgson was ordained by Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, the son of William Wilberforce. Wilberforce is probably best remembered today for his opposition to Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution at a debate in 1860. Around 1863, Carroll also developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family. Carroll was an early member of the Society for Psychical Research, and one of his letters suggests that he accepted as real what was then called “thought reading.”[61]

In 1872, Carroll, together with his friend the Pre-Raphaelite painter and illustrator Arthur Hughes, took “a splendid walk to Fairyland,” a haunted woodland area near Guildford in Surrey which was popular with Victorian artists and writers.[62] In Carroll’s library were books from non-scientific and occult subjects, including spiritualism, Christian mysticism, medieval astronomy and even Buddhism. According to Carroll, the human is capable of various physical states, with varying degrees of consciousness. The first is ordinary state, with no consciousness of the presence of fairies. The second is the “eerie” state, in which he is also conscious of the presence of fairies. And last is a form of trance, in which he migrates to the actual Fairyland, and is conscious of the presence of fairies.[63]

The character of Alice was inspired by one of his many “child-friends,” Alice Liddell, daughter of the Dean of Christ Church, Henry Liddell. Several biographers have suggested that Dodgson’s interest in children had an erotic element, including Morton N. Cohen in his Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1995), Donald Thomas in his Lewis Carroll: A Portrait with Background (1995), and Michael Bakewell in his Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1996). Rumors of pedophilia long had been attached to Dodgson, who was, as Cohen notes, “the subject of whispers and wagging tongues.”[64] As Carroll’s biographer Jenny Woolf writes in a 2010 essay for the Smithsonian, “of the approximately 3,000 photographs Dodgson made in his life, just over half are of children—30 of whom are depicted nude or semi-nude.”[65] After several years of friendship, the Liddells forbade Dodgson to see Alice or her sisters. It is not known why. However, in later years, Alice’s sister Lorina informed her that she told a biographer, “I said his manner became too affectionate to you as you grew older. And that mother spoke to him about it, and that offended him. So he ceased coming to visit us again.”[66]

[1] Rabbi A. Kook (Orot Hakodesh Book 2 Chap. 537).

[2] Edward Munch: Behind the Scream. [http://yalepress.yale.edu/yupbooks/excerpts/munch.asp]

[3] Robert E. Schofield (December 1966), “The Lunar Society of Birmingham; A Bicentenary Appraisal.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 21 (2), pp. 146–147.

[4] Eugene F. Provenzo, Jr., John P. Renaud. Encyclopedia of the Social and Cultural Foundations of Education: A-H ; 2, I-Z ; 3, Biographies, visual history, index (SAGE, 2009), p. 329.

[5] Ruth Barton. “ ‘Huxley, Lubbock, and Half a Dozen Others’: Professionals and Gentlemen in the Formation of the X Club, 1851–1864,” Isis,Vol. 89, No. 3 (September, 1998), pp. 411, 434.

[6] “Darwin and design: historical essay.” Darwin Correspondence Project. 2007.

[7] Sherrie L. Lyons. Thomas Henry Huxley: the evolution of a scientist (New York 1999). p. 11

[8] Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 4807 – Hooker, J. D. to Darwin, C. R., (7–8 Apr 1865).

[9] Ruth Barton, “‘Huxley, Lubbock, and Half a Dozen Others’: Professionals and Gentlemen in the Formation of the X Club, 1851–1864,” Isis, Vol. 89, No. 3 (September, 1998), p. 412.

[10] Chard, Leslie. “Bookseller to publisher: Joseph Johnson and the English book trade, 1760–1810.” The Library. 5th series. 32 (1977), p. 150.

[11] “Fuseli, Henry.” In Hugh Chisholm (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1911).

[12] Per Faxneld & Jesper Aa. Petersen. The Devil’s Party: Satanism in Modernity (Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 42.

[13] Philip Coppens. “William Blake: What paintings of visions come.” Retrieved from http://www.philipcoppens.com/blake.html

[14] Adriana Craciun. “Romantic Satanism and the Rise of Nineteenth-Century Women's Poetry Author(s).” New Literary History, Autumn, 2003, Vol. 34, No. 4, Multicultural Essays (Autumn, 2003), pp. 703.

[15] A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on Wollstonecrafl’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, ed. Adriana Craciun (London, 2002), pp. 48-49;

[16] Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine (July 1798), 98–9.

[17] C.M. Brown. “Mary Wollstonecraft, or the Female Illuminati: The Campaignagainst Women and “Modern Philosophy” in the Early Republic.” Journal of the Early Republic, 15 (1995), pp. 395.

[18] John Robison. Proofs of a Conspiracy (1798), p. 174.

[19] Ibid., p. 193-4.

[20] George Rudé. Revolutionary Europe: 1783–1815 (1964), p. 183.

[21] Paine. The Age of Reason (1974), 50.

[22] Ibid., Part II, Section 4.

[23] Per Faxneld & Jesper Aa. Petersen. The Devil’s Party: Satanism in Modernity (Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 43.

[24] Percy Bysshe Shelley. Queen Mab, Canto VII, Note 13.

[25] James Bieri & S. James Bieri. Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Biography: Youth's Unextinguished Fire, 1792-1816 (University of Delaware Press, 2004), p. 85.

[26] Brian L. Silver. The Ascent of Science (Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 7.

[27] Berthold Schoene-Harwood. Mary Shelley: Frankenstein (Columbia University Press, 2000), p.138.

[28] Thomas Jefferson Hogg. The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley, Vol. II (London, 1858), pp. Melanson. Perfectibilists (Kindle Locations 3584-3588).

[29] Hogg, op. cit., p. 189; cited in Melanson. Perfectibilists (Kindle Locations 3589-3592).

[30] Miranda Seymour. Mary Shelley (Grove Press, 2002), p. 111; cited in Melanson. Perfectibilists (Kindle Locations 3607-3611).

[31] “Romanticism.” Encyclopædia Britannica (Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. January 21, 2019).

[32] Richard Lansdown. “Byron and the Carbonari.” History Today (Volume: 41 Issue: 5)

[33] Stars and Stripes Website, “Frankenstein Castle: A frightfully nice place for Halloween celebration,” Retrieved 21 April 2014.

[34] Steven Conn. History’s Shadow: Native Americans and Historical Consciousness in the Nineteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), pp.14, 123-124.

[35] See Sanborn, F.B., ed. The Romance of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, John Howard Payne and Washington Irving (Boston: Bibliophile Society, 1907).

[36] Gerry Bowler. The World Encyclopedia of Christmas (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd., 2000), pp. 44.

[37] David Livingstone. Ordo ab Chao, Volume Two, Chapter 1: The Elizabethan Age.

[38] John T. Shawcross. John Milton (University Press of Kentucky, 1993), p. 249.

[39] Sally Ledger & Holly Furneaux, eds. Charles Dickens in Context (Cambridge University Press, 2011). p. 178.

[40] Penne L. Restad. Christmas in America: a History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

[41] Jeffrey Burton Russell. The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History (Ithica: Cornell University Press, 1988), p. 114.

[42] Laura Dassow Walls. The Passage to Cosmos: Alexander von Humboldt and the Shaping of America (University of Chicago Press, 2009), pp. 117–118

[43] Stephen J. Gould. “The late birth of a flat Earth,” in Dinosaur in a Haystack: Reflections in Natural History (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1997), pp. 38–50.

[44] “Bonesmen 1833–1899.” Fleshing Out Skull and Bones. Retrieved from http://area907.info/911/index.php?Bonesmen2

[45] “APS Member History.” search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved from https://search.amphilsoc.org/memhist/search?creator=&title=&subject=&subdiv=&mem=&year=1876&year-max=&dead=&keyword=&smode=advanced

[46] James R. Moore. The Post-Darwinian Controversies (Cambridge University Press, 1981), p. 10.

[47] Clement Greenberg. “Modernism and Postmodernism.” William Dobell Memorial Lecture, Sydney, Australia, Oct 31, 1979. Arts 54, No.6 (February 1980).

[48] Neil McKenna. The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde. (Century, 2003) p. 33.

[49] Michael Robertson. Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples (Princeton University Press, 2010), p. 135.

[50] Philip Callow. From Noon to Starry Night: A Life of Walt Whitman (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1992), p. 232.

[51] Sarah M. Pike. New Age and Neopagan Religions in America, Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

[52] Joel Porte. In Respect to Egotism: Studies in American Romantic Writing (Cambridge University Press, 1991)), p. 23.

[53] Joanne Wilkes. Lord Byron and Madame de Staël: Born for Opposition (London: Ashgate, 1999).

[54] W. Potter. “The Free Religious Association: Its Twenty-five Years and Their Meaning” (1892), pp. 8-9.

[55] Michael Flannery. “Finding Darwin’s Real God.” Evolution News & Science Today (October 11, 2012). Retrieved from https://evolutionnews.org/2012/10/finding_darwins_1/

[56] Benny Kraut. “Judaism Triumphant: Isaac Mayer Wise on Unitarianism and Liberal Christianity.” AJS Review, 7, pp. 179-230.

[57] Emil G. Hirsch. “The Doctrine of Evolution and Judaism,” in Some Modern Problems and Their Bearing on Judaism Reform Advocate Library (Chicago: Bloch & Newman, 1903), pp. 25-46.

[58] Philip F. Gura. American Transcendentalism: A History (New York: Hill and Wang, 2007), p. 172

[59] Judith Thurman. “The Desires of Margaret Fuller.” The New Yorker (March 25, 2013).

[60] Van Akin Burd. “Ruskin on his sexuality: a lost source.” Philological Quarterly, (Fall, 2007).

[61] Renée Hayness. The Society for Psychical Research, 1882–1982 A History. (London: Macdonald & Co, 1982). pp. 13–14.

[62] Lewis Carroll. Lewis Carroll’s Diaries: The Private Journals of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Luton: Lewis Carroll Society, 1993), VI, p. 354.

[63] Sylvie & Bruno Concluded. The Complete Illustrated Works of Lewis Carroll (London: Chancellor, 1982), p. 441.

[64] Cited in Julia Keller. “Is the Innocence of ‘Alice’ Forever Lost?” Chicago Tribune (February 28, 1999).

[65] Jenny Woolf. “Lewis Carroll’s Shifting Reputation.” Smithsonian Magazine (April 2010).

[66] The Secret World of Lewis Carroll (BBC, 2015).

Volume Two

The Elizabethan Age

The Great Conjunction

The Alchemical Wedding

The Rosicrucian Furore

The Invisible College

1666

The Royal Society

America

Redemption Through Sin

Oriental Kabbalah

The Grand Lodge

The Illuminati

The Asiatic Brethren

The American Revolution

Haskalah

The Aryan Myth

The Carbonari

The American Civil War

God is Dead

Theosophy

Shambhala