8. America

Sacred destiny

Popular history in the United States repeats the notion that many of the British colonies in North American were settled in the seventeenth century by Englishmen fleeing religious persecution at home.[1] They supported the efforts of their leaders to create “a City upon a Hill” or a “Holy Experiment,” whose success would prove that God’s plan could be successfully realized in the American wilderness. Ultimately, their efforts inspired their successors to establish the legacy of secularism in the United States, permanently separating Church and State, in order to avoid the same persecutions their predecessors had endured.

In reality, the founding of America was a Rosicrucian mission, inspired by Campanelli’s City of the Sun and Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis, to set up a haven where they would be free to practice their heretical views. To understand the Masonic perspective of this history, Manly P. Hall in The Secret Destiny of America explained:

Bacon quickly realized that here in the new world was the proper environment for the accomplishment of his great dream, the establishment of the philosophic empire. It must be remembered that Bacon did not play a lone hand; he was the head of a secret society including in its membership the most brilliant intellectuals of his day. All these men were bound together by a common oath to labor in the cause of a world democracy. Bacon’s society of the unknown philosophers included men of high rank and broad influence. Together with Bacon, they devised the colonization scheme.[2]

As explained by Pike, the goal of Freemasonry is to fulfill the End Times prophecies of the Book of Revelation. That mission, according to occultists like Manly P. Hall, is the fulfillment of a “Universal Plan.” It is also known as “The Great Work,” (Latin: Magnum opus) an alchemical term for the process of working with the prima materia to create the philosopher’s stone. It has been used to describe personal and spiritual transmutation in the Hermetic tradition, believed to have been preserved over the centuries by the predecessors of Freemasonry, the Templar Knights and the Rosicrucians. It is interpreted from the esoteric teachings of the Jewish mystical tradition of the Kabbalah, according to which this fulfillment will come from a resolution of all opposites, leading to order out of chaos, or “ordo ab chao” in Latin, according to the Masonic dictum.

Pike wrote in his tome Morals and Dogma, “So that the Great Work is more than a chemical operation; it is a real creation of the human word initiated into the power of the Word of God.”[3] The influential Golden Dawn defines the Great Work as “…refers to the path of human spiritual evolution, growth and illumination, which is the goal of ceremonial magic.”[4] And finally, Aleister Crowley, a former member of the Golden Dawn and the godfather of twentieth century Satanism, explained: “The Great Work is the uniting of opposites. It may mean the uniting of the soul with God, of the microcosm with the macrocosm, of the female with the male, of the ego with the non-ego.”[5

The means is magic, which according to Eliphas Levi derives from a force in nature which “is immeasurably more powerful than steam, and by means of which a single man, who knows how to adapt and direct it, might upset and alter the face of the world.”[6] The Great Work within Aleister Crowley’s Satanic cult of Thelema, is regarded as the process of attaining knowledge and conversation with the “Holy Guardian Angel” and learning and accomplishing one’s “True Will.” Thus, according to Masonic author Manly P. Hall: “When the Mason learns that the key to the warrior on the block is the proper application of the dynamo of living power, he has learned the mystery of his Craft. The seething energies of Lucifer are in his hands…”[7]

Thus, in Freemasonry, the establishment of American “democracy” is perceived to be at the forefront of a sacred destiny, the reconstruction of the Temple of Solomon, as an allegory for the establishment of a Novus Ordo Seclorum (“New Order of the Ages”). In the Encyclopaedia of Freemasonry, Masonic historian Albert Mackey affirms: “Of all the objects which constitute the Masonic science of symbolism, the most important, the most cherished, by the Mason, and by far the most significant, is the Temple of Jerusalem.”[8] Edward Waite writing in A New Encyclopedia of Freemasonry and of Cognate Instituted Mysteries: The Rites, Literature and History, declares: “in several High Grades [of Masonry] we hear of a secret intention to build yet another temple at Jerusalem.”[9] As Waite explains, “There is a time… to come when the Holy One shall remember His people Israel and the Lord shall build the House. Such is the Zoharic testimony.”[10]

That mission, according to occultists like Manly P. Hall, is American Democracy, as the fulfillment of a “Universal Plan.” Hall believed there had existed since long ago a group of enlightened individuals united as the Order of the Quest. All were searching for one and the same thing: a perfected social order, Plato’s commonwealth, the government of the philosopher-kings. According to Hall, “For more than three thousand years, secret societies have labored to create the background of knowledge necessary to the establishment of an enlightened democracy among the nations of the world.” Hall further states:

World democracy was the secret dream of the great classical philosophers. Toward the accomplishment of this greatest of all human ends they outlined programs of education, religion, and social conduct directed to the ultimate achievement of a practical and universal brotherhood. And in order to accomplish their purposes more effectively, these ancient scholars bound themselves with certain mystic ties into a broad confraternity. In Egypt, Greece, India, and China, the State Mysteries came into existence. Orders of initiated priestphilosophers were formed as a sovereign body to instruct, advise, and direct the rulers of the States.

And so it is from the remote past, from the deep shadows of the medieval world as well as from the early struggles of more modern times, that the power of American democracy has come. But we are only on the threshold of the democratic state. Not only must we preserve that which we have gained through ages of striving, we must also perfect the plan of the ages, setting up here the machinery for a world brotherhood of nations and races.

This is our duty, and our glorious opportunity.[11]

As expressed by Hall in The Secret Destiny of America, it is the United States, supposedly known to the ancients as Atlantis, which was chosen for this sacred purpose. The Scottish Rite Journal called Hall “Masonry’s Greatest Philosopher.”[12] Hall was a 33º Mason and the founder of the Philosophical Research Society. In 1928, at only twenty-seven, he published The Secret Teachings of All Ages, a massive compendium of the mystical and esoteric philosophies of antiquity. Hall dedicated the book to “the proposition that concealed within the emblematic figures, allegories and rituals of the ancients is a secret doctrine concerning the inner mysteries of life, which doctrine has been preserved in toto among a small band of initiated minds.” The book won the admiration of figures ranging from General John Pershing to Elvis Presley and Ronald Reagan. As well, Dan Brown, author of The Da Vinci Code, cites it as a key source. Hall’s The Secret Destiny of America was based on a speech he gave in 1942 to a sold-out audience at Carnegie Hall. He returned in 1945 for another well-attended lecture, titled: “Plato’s Prophecy of Worldwide Democracy.”

Fortunate Isles

Insula Fortunata (Fortunate Isles), drawn east of the Canaries on this map depicting St. Brendan, a sixth-century Irish monk who, according to legend, journeyed deep into the Atlantic.

Johannes Valentinus Andreae (1586 – 1654) reputed author of the Rosicrucian manifestoes

Columbus as well was in search of the lost continent of Atlantis.[14] Long popular in occult circles, the Atlantis myth was first mentioned by Plato, referring to a lost continent that had existed in the Atlantic Ocean. Mediaeval European writers, who received the tale from Arab geographers, believed the mythical island to have actually existed, and later writers tried to identify it with an actual country. When America was discovered, the Spanish historian Francisco Lopez de Gomara, in his General History of the Indies, suggested that Plato’s Atlantis and the new continents were the same.

An influential example of the Atlantis legend is found in Ben Jonson’s The Fortunate Isles and Their Union, which satirized the Rosicrucians. In spite of its tone, in 1619 Jonson had met Joachim Morsius, a close associate of Johann Valentin Andreae who promoted the Lion of the North prophecy with Johannes Bureus.[15] Designed by Inigo Jones, The Fortunate Isles was the major entertainment of the 1624–25 Christmas season at the Stuart Court. For source material for his text, Jonson relied upon the Speculum Sophicum Rhodo-strautoricum of Teophilus Schweigardt (1618) and the Artis Kabbalisticae of Pierre Morestel (1621). Jonson describes the moving castle of Julianus de Campis, the Rosicrucian pseudonym of the Dutch-born engineer Cornelius Drebbel, who demonstrated many mechanical inventions in the courts of James I and Prince Henry in 1605-1611.[16] The name Johphiel derives from Cornelius Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia. The Fortunate Isles opens with the entrance of Johphiel, “an airy spirit” who is supposedly “the intelligence of Jupiter’s sphere.” Johphiel has a long conversation with Merefool, “a melancholic student,” which involves much material on the then controversial subject of “the brethren of the Rosy Cross.”

The Fortunate Isles were semi-legendary islands in the Atlantic Ocean and were one of the most persistent themes in European mythology. The name Fortunate Isles, or sometimes Blessed Isles or Isles of the Blest, was the name given it by the ancient Greeks where mortals lived forever in an earthly paradise with the gods and heroes of Greek mythology.[17] Later on the islands were said to lie in the Western Ocean near the encircling River Oceanus, as well as Madeira, the Canary Islands, the Azores, Cape Verde, Bermuda, and the Lesser Antilles.

Detail of the Atlantic Ocean envisioned by Martin Behaim.

The Antilles were named after Antilia, an alternate name, along with Macaria, used by Samuel Hartlib for his Invisible College and related to the college described by Andreae in his Christianae Societatis Imago.[18] Antilia was a phantom island that was reputed during the fifteenth century age of exploration to lie in the Atlantic Ocean, far to the west of Portugal and Spain. The island also went by the name of Isle of Seven Cities. It originated from an old Iberian legend, set during the Moorish conquest of Spain in the eighth century. Seeking to flee from their conquerors, seven Christian Visigothic bishops embarked with their flocks on ships and set sail westwards into the Atlantic Ocean, eventually landing on an island where they founded seven settlements. The island makes its first explicit appearance as a large rectangular island in the 1424 portolan chart of the Venetian cartographer Zuane Pizzigano. The following year, in what may be the first attempt to represent the new world, the island appeared on a portolano belonging to the Library of Weimar, then on a 1436 map prepared by the Venetian Andrea Bianco, and thereafter on nearly all contemporary maps.[19]

The name “Antilia” was a appeared in Martin Behaim’s famous Nuremberg globe of 1492, placed in the south-west of Portugal, far out in the Atlantic ocean. Behaim had learned of the story during his Portuguese travels. In that same year, Behaim’s friend Christopher Columbus set out on his historic journey to Asia, citing the island as the perfect halfway house by the authority of Paul Toscanelli.[20] Columbus had supposedly gained charts and descriptions from a Spanish navigator, who had “sojourned… and died also” at Columbus’ home in Madeira, after having landed on Antillia.[21] Others, following Peter Martyr d’Anghiera, suggested contenders in the West Indies for Antillia’s heritage, and as a result the Caribbean islands became known as the Antilles.

New Atlantis

Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626)

In the City of the Sun, which was inspired by the Picatrix and by Plato’s Republic and the description of Atlantis in Timaeus, a Genoese sea-captain who has wandered over the whole earth carries on a dialogue with his host, a Grandmaster of the Knights Hospitallers, which he relates his experiences in the City of the Sun, in Taprobane, “immediately under the equator,” which he describes a theocratic society where goods, women and children are held in common. In the final part of the work, Campanella provides a prophesy in the veiled language of astrology that the Spanish kings, in alliance with the Pope, are destined to be the instruments of a Divine Plan: the final victory of the True Faith and its diffusion in the whole world.

Bacon’s New Atlantis (1927), significantly resembles Johann Valentin Andreae’s Description of the Republic of Christianopolis. The island on which the utopian city of Christianopolis stood was discovered by Christian Rosencreutz on the voyage on which he was starting at the end of the The Chymical Wedding. In Christianopolis spiritual fulfilment was primary goal of each individual where scientific pursuits were the highest intellectual calling. Andreae’s island also depicts a great technological innovations, with many industries separated in different zones which supplied the population’s needs, which shows great resemblance to Bacon’s scientific methods and purposes.

Bacon suggests that the continent of America was the former Atlantis where there existed an advanced race during the Golden Age of civilization. Bacon tells the story of a country ruled by philosopher-scientists in their great college called Solomon’s House, which inspired the founding of the Royal Society. According to Bacon’s account, also living in the land, beside the natives, were Hebrews, Persians, and Indians. It is a Jew named Joabin who enabled Bacon’s hero to meet with “the father of Salomon’s House.” According to Joabin, the people of Bensalem are descended from Abraham, from his son Nachoran, and their laws were given by Moses, who “by a secret cabala ordained the laws of Bensalem which they now use.” According to the narrator, while Jews usually tend to despise Christianity, the Jews of Bensalem “give unto our Saviour many high attributes, and love the nation of Bensalem extremely.” Joabin acknowledged that Christ was born of a virgin and that he was more than a man, and believed God made him ruler of the seraphims who guard his throne. Christ is referred to as Milken Way, and the Eliah of the Messiah. According to narrator, the Jews of Bensalem believed that:

…when the Messiah should come, and sit in his throne at Hierusalem, the king of Bensalem should sit at his feet, whereas other kings should keep a great distance. But yet setting aside these Jewish dreams, the man was a wise man, and learned, and of great policy, and excellently seen in the laws and customs of that nation.

Ben Jonson referenced the idea related to Solomon’s House in his masque, The Fortunate Isles and Their Union, which satirized the Rosicrucians. Hartlib specifically mentions Solomon’s House with reference to the kinds of institutions he would like to see created.[22] In The New Atlantis, they described the purpose of their brotherhood: “The end of our foundation is the knowledge of causes, and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of human empire, to the effecting of all things possible.” Having gained superior knowledge imparted to them by heavenly beings, they possessed flying machines and ships with which they travel under the sea. The inhabitants of New Atlantis would appear to have achieved the great instauration of learning and have therefore returned to the state of Adam in Paradise before the Fall—the objective of advancement both for Bacon and for the authors of the Rosicrucian manifestos.[23]

Britannia

Spanish Armada (1588).

The General and Rare Memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation (1577) by John Dee is one of the first texts to express the idea of a “British Empire.” The title page, designed by Dee himself, Dee included a figure of Britannia kneeling by the shore beseeching Elizabeth I to protect her nation by strengthening her navy.

The esotericism of the Elizabeth Age was also coupled with imperial ambitions. It was an age of exploration and expansion abroad, the seafaring prowess of English adventurers such as Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540 – 1596), and the Spanish Armada was repulsed. England was also well-off compared to the other nations of Europe. North America attracted particular attention in England, as the idea grew that a north-west passage to the East could be discovered. John Bale, writing in the 1540s, had identified the Protestant Church of England as an actor in the historical struggle with the “false church” of Catholicism, supported by his interpretations of the Book of Revelation. The views of John Foxe, author of what is popularly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, became widely accepted within the Church of England for a generation and more. According to Foxe, a war against the Antichrist was being waged by the English people, but led by the Christian Emperor (echoing Constantine I) who was identified with Elizabeth I. Foxe, referring to it as “this my-country church of England,” characterized England’s destiny as the elect nation” of God.[24]

John Bale, writing in the 1540s, had identified the Protestant Church of England as an actor in the historical struggle with the “false church” of Catholicism, supported by his interpretations of the Book of Revelation. The views of John Foxe, author of what is popularly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, became widely accepted within the Church of England for a generation and more. According to Foxe, a war against the Antichrist was being waged by the English people, but led by the Christian Emperor (echoing Constantine I) who was identified with Elizabeth I. Foxe, referring to it as “this my-country church of England,” characterized England's destiny as the “elect nation” of God.[25]

Like Spenser’s Faerie Queene, the British accepted the prophecy of Merlin, which proclaimed that the Saxons would rule over the Britons until King Arthur again restored them to their rightful place as rulers. The prophecy was related by Geoffrey of Monmouth (1100 – 1155), a cleric and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography and the popularity of tales of King Arthur. He is best known for his chronicle Historia Regum Britanniae, which relates the purported history of Britain from its first settlement by Brutus, a descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas. The prophecy was adopted by the British people and eventually used by the Tudors who claimed to be descendants of Arthur and the rightful rulers of Britain.[26]

It is John Dee who has been credited with the coining of the term “British Empire.” Believing himself to be of ancient British royal descent as well, Dee identified completely with the British imperial myth around Elizabeth I.[27] According to Donald Tyson, “It was Dee’s plan to use the complex system of magic communicated by the angels to advance the expansionist policies of his sovereign, Elizabeth the First.”[28] Dee laid the foundations for British imperialism by claiming that conquests by King Arthur had given Elizabeth I title to foreign lands such as Greenland, Iceland, Friesland, the northern islands towards Russia and the North Pole. He claimed that the New World was appointed by Providence for the British to influence and rule. In his 1576 General and rare memorials pertayning to the Perfect Arte of Navigation, Dee advocated a policy of political and economic strengthening of England and imperial expansion through colonization and maritime supremacy into the New World.

In the frontispiece of the book Dee included a figure of Britannia kneeling by the shore beseeching Elizabeth I to protect her empire by strengthening her navy.[29] Britannia is an ancient term for Great Britain and also a female personification of the island. In the second century, Roman Britannia came to be personified as a goddess armed with a trident and shield and wearing, like the Greek Athena, a phallic Corinthian helmet. Britannia is later depicted with a lion at her feet, the heraldic symbol the Tribe of Judah. In France she is known as Lady Liberty, in Switzerland as Helvetia, in Germany as Germania, in Poland as Polonia, and in Ireland as Hibernia.

When Philip II of Spain, Grand Master of the Order of Santiago, attempted to invade England with the Spanish Armada in 1588, Elizabeth had consulted John Dee on how to best counter the advancing Spanish ships, he advised her and Sir Francis Drake to refrain from pursuit because the Spanish fleet would be broken up by storm. When a storm did destroy the Armada and aided the English victory many courtiers were convinced that Dee had conjured it. Thus Dee became the model for the character of the sorcerer Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. But it was also believed Drake was a wizard and sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for success over the Spanish. It is claimed that he also organized several covens of witches to work magically to raise the storm and prevent the invasion.[30]

Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540 – 1596), also known as El Draco, “the Dragon.”

One of Dee’s staunchest supporters at court was Sir Christopher Hatton who was the main backer for Sir Francis Drake’s world voyage. Drake’s exploits were legendary, making him a hero to the English, but a pirate to the Spaniards to whom he was known as El Draco, “the Dragon.” Drake also carried out the second circumnavigation of the world, from 1577 to 1580. Drake was Vice-Admiral of the English fleet in 1588 against the Spanish Armada, whose defeat was supposedly caused through Dee’s sorcery. But it was also believed Drake was a wizard and sold his soul to the Devil in exchange for success over the Spanish. It is claimed that he also organized several covens of witches to work magically to raise the storm and prevent the invasion.[31]

The quartermaster for Drake’s 1577 global navigation was named as Moses the Jew. Subatol Deul, who would become one of the most feared pirates in the world, formed an alliance with Drake’s son Henry Drake. Subatol was the son of Sudel Deul, a sixteenth century Jewish physician and early explorer of the Americas who is credited with introducing the potato to Europeans. Together, Subatol and Henry formed the “Brotherhood of the Black Flag,” and attacked Spanish ships off the coast of present-day Chile. It is said that the duo buried 6,000 pounds of Spanish gold and an even larger amount of silver near the Guayacan harbor. The treasure has not been found, though seekers have discovered documents written partly in Hebrew, possibly written by Subatol.[32]

Sir Walter Raleigh (1554-1618)

Dee was a close friend of the spy and explorer Sir Walter Raleigh (1554 – 1618). Instrumental in the English colonization of North America, Raleigh was granted a royal patent to explore Virginia, which paved the way for future English settlements. Raleigh as well, was interested in magic. In his History of the World, Raleigh explains that for the most part the reputation of magic was unfairly maligned, and explains that in former times, magicians were known as wisemen: to the Persians as Magi, to the Babylonians as Chaldeans, to Greeks as philosophers, and to Jews Kabbalists, “who better understood the power of nature, and how to apply things that work to things that suffer.”[33] Raleigh’s half-brother Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 – 1583) tried to establish a permanent colony in North America and Newfoundland, without much success. Gilbert then took a more southerly route across the Atlantic. In 1584, he sent out an exploratory expedition which located Roanoke Island, now in North Carolina, and returned to England that autumn. The following year he sent out a military expedition under Sir Richard Grenville, which built a fort there and remained until spring 1586.

Virginia Company

Jennie A. Brownscombe’s The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth (1621)

Bacon played a leading role in creating the British colonies, especially in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Newfoundland in northeastern Canada. Following in the steps of John Dee, Bacon lent his group’s support behind the English plan to colonize America. An attempt to colonize the New World was made under the initial leadership in 1602 of Bartholomew Gosnold (1571 – 1607), a cousin twice over of Bacon and four times over of the 17th Earl of Oxford, whom Oxfordians believe was Shakespeare. Gosnold was an English lawyer, explorer, and privateer and a friend of Richard Hakluyt and sailed with Walter Raleigh. Gosnold was instrumental in founding the Virginia Company of London, and Jamestown in colonial America. Gosnold’s voyage was funded by the Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s patron. He led the first recorded European expedition to Cape Cod. He is considered by Preservation Virginia to be the “prime mover of the colonization of Virginia.” Following the coastline for several days, he discovered Martha’s Vineyard and named it after his daughter, Martha, and established a small post on Cuttyhunk Island, one of the Elizabeth Islands, near Gosnold, now in Massachusetts.

Bacon claimed that the New Kingdom on Earth which was Virginia exemplified the Kingdom of Heaven. Bacon’s involvement in American colonization is demonstrated by William Strachey, who in 1618 dedicated a manuscript copy of his Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britania to Bacon:

Your Lordship ever approving yourself a most noble fautor [favourer] of the Virginia plantation, being from the beginning (with other lords and earls) of the principal counsell applied to propagate and guide it.[34]

Bacon is listed in the 1609 charter as a shareholder of the Virginia Company of London and one of the 52 members of the Virginia Council. The Virginia Company refers collectively to a joint stock company chartered by James I in 1606, with the purposes of establishing settlements on the coast of North America. The two companies, called the “Virginia Company of London” (or the London Company) and the “Virginia Company of Plymouth” (or Plymouth Company) operated with identical charters but with differing territories. An area of overlapping territory was created within which the two companies were not permitted to establish colonies within one hundred miles of each other. The Plymouth Company never fulfilled its charter, and its territory that later became New England was at that time also claimed by England.

The Mayflower

Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor by William Halsall (1882)

The Plymouth Company was permitted to establish settlements roughly between the upper reaches of the Chesapeake Bay and the current US-Canada border. In 1607, the Plymouth Company established the Popham Colony along the Kennebec River in present day Maine. However, it was abandoned after about a year, and the Plymouth Company became inactive. With the religious Pilgrims who arrived aboard the iconic Mayflower, whose leaders were Rosicrucians, a successor company to the Plymouth Company eventually established a permanent settlement in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620, in what is now New England.

William Brewster (1566 – 1644)

According to Nicholas Hagger in The Secret Founding of America: The Real Story of Freemasons, Puritans, & the Battle for The New World, “Indeed, so close were Puritanism and Rosicrucianism in essence that it can be said that the Puritan philosophy was actually Rosicrucian.”[35] The Puritans were a group of English Reformed Protestants in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries who sought to “purify” the Church of England from all Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had only been partially reformed. However, when James I took the throne in 1603, he declared he would put an end to church reform movements, and deal harshly with radical critics of the Church of England. A group dissatisfied with the efforts of the Puritans, decided they would sever all ties, and became known as Separatists, led by John Robinson and William Brewster. However, in 1608, shortly after James I declared the Separatist Church illegal, the congregation emigrated to Leiden where they were joined by Rosicrucian circles. It was here that Brewster set up a new printing company in order to publish leaflets promoting the Separatist aims and pamphlets supporting the Rosicrucian cause.[36]

In November 1620, following the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War, which erupted after the Habsburgs set out to crush the Rosicrucian movement, Frederick V and Elizabeth Stuart fled into exile to The Hague in the Netherlands, and numerous Rosicrucians migrated with them. Frederick and Elizabeth sought refuge in the Netherlands with Frederick’s uncle, Maurice, the prince of Orange, the son of William the Silent, who was a strong supporter of their cause and sympathized with the Rosicrucians. During the first two decades of the seventeenth century, and until his death in 1625, Maurice was the Stadtholder of the Netherlands provinces of Holland and Zeeland, the southern coastal states, which included the towns of Amsterdam, Leiden, and The Hague. It was Maurice, in fact, who had offered the English Separatists a safe haven in Leiden in 1608.[37]

Pierre Du Gua, Sieur de Monts (c. 1558 – 1628)

It was to Brewster’s home in Leiden in 1615 where fled Pierre Du Gua, Sieur de Monts (c. 1558 – 1628), a French merchant, explorer and colonizer with Rosicrucian connections.[38] Du Gua, a Calvinist, founded the first permanent French settlement in Canada. He travelled to northeastern North America for the first time in 1599 with Pierre de Chauvin de Tonnetuit. He sent Samuel de Champlain to open a colony at Quebec in 1608, thus playing a major role in the foundation of the first permanent French colony in North America.

Du Gua was also a member of the School of Night, a modern name for a group of men centered on Sir Walter Raleigh that was once referred to in 1592 as the “School of Atheism.”[39] The group supposedly included poets and scientists Christopher Marlowe, George Chapman and Thomas Harriot. It was alleged that each of these men studied science, philosophy, and religion, and all were suspected of atheism. Marlowe was the author of Doctor Faustus, which is the most controversial Elizabethan play outside of Shakespeare. It is based on the German story of Faust, a highly successful scholar who is dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil, and exchange his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. There is no firm evidence that all of these men were known to each other, but speculation about their connections features prominently in some writing about the Elizabethan era.

When the Fama Fraternitatis publicly announced the existence of the Rosicrucian fraternity in 1610, the document was circulated in Paris, and one of the first to publicly respond to it was Du Gua.[40] In 1615, the Queen Mother discovered Du Gua’s authorship of anti-government pamphlets and ordered his arrest. With a price on his head, Du Gua fled to the Netherlands where he stayed with Brewster. Brewster had been a student of Greek and Latin at Cambridge University in the mid-1580s, at the same time as William Shakespeare’s colleague Christopher Marlowe, through whom he had met Walter Raleigh and began to attend the meetings of the School of Night, and subsequently struck up a close friendship with Du Gua. The last known Rosicrucian document, published in Latin by Brewster in Leiden in 1615, was called the Confessio Fraternitatis, or “Confession of the Fraternity,” and was written under a pseudonym, Philip A Gabella (Philip the Cabalist), while some scholars have proposed that its true author was Pierre Du Gua.[41]

Other Rosicrucians also congregated in Leiden at precisely the same time, in February 1620, just prior to the Mayflower’s voyage. Johann Valentin Andreae, the author of the Fama Fraternitatis, was already there, having left Germany when war broke out. Fulke Greville, whose London house was used for the early meetings of the School of Night and who had been present at Elizabeth’s “Alchemical Wedding,” was there. Francis Bacon was visiting Maurice of Orange in his official position as English lord chancellor to discuss the legality of a trade treaty with the Netherlands. The playwright Ben Jonson was present in Leiden, performing a play at a new theater. And the architect Inigo Jones, although not staying in Leiden itself, was in nearby Amsterdam working on plans for a church he had been commissioned to build in the city.

Passengers of the Mayflower signing the "Mayflower Compact" including Carver, Winston, Alden, Myles Standish, Howland, Bradford, Allerton, and Fuller.

At that very time, the English Separatists in the city decided the only hope for religious freedom lay in North America. In the middle of July 1620, a large part of the Separatist congregation sailed for the New World aboard a ship named the Mayflower, with 102 passengers, Brewster, and all the Pilgrim Fathers, the name later given to the original nine elders of the church. On November 9, 1620, they sighted land, which was present-day Cape Cod.

City Upon a Hill

The Arrival of the Pilgrims Fathers by Antonio Gilbert (1864)

According to Rosicrucian legend, Bacon’s The New Atlantis inspired the founding of a colony of Rosicrucians in America in 1694 under the leadership of Grand Master Johannes Kelpius (1667 – 1708). Born in Transylvania, Kelpius was a follower of Johann Jacob Zimmerman, an avid disciple of Jacob Boehme, who was also “intimately acquainted” with Benjamin Furly.[42] Zimmerman was referred to by German authorities as “most learned astrologer, magician and cabbalist.”[43] With his followers in the Society of the Woman in the Wilderness, Kelpius came to believe that the end of the world would occur in 1694. This belief, based on an elaborate interpretation of a passage from the Book of Revelation, anticipated the advent of a heavenly kingdom somewhere in the wilderness during that year. Answering Penn’s call to establish a godly country in his newly acquired American lands, Kelpius felt that Pennsylvania, given its reputation for religious toleration at the edge of a barely settled wilderness, was the best place to be.

William Penn (1644 – 1718), early Quaker, and founder of the English North American colony the Province of Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania was founded by William Penn, a friend of John Dury of the Hartlib Circle. Penn was also a member of the Lantern, a circle around Rotterdam merchant Benjamin Furly, which included alchemists van Helmont, Lady Conway, Henry More and John Locke. Furly and van Helmont were also connected with a group of students of Jacob Boehme, which included Serrarius, and who also knew and associated with Baruch Spinoza. Furly, like Penn, was a Quaker and a close supporter of George Fox, the founder of the movement, which provided the guiding principles of the new state of Pennsylvania.

At some time, Penn came into contact with German Rosicrucian Jacob Boehme’s teachings and the Rosicrucians who introduced him into the deeper mystical and metaphysical studies. In New World Mystics, Dr. Palo writes:

Penn had a more than passing interest in mysticism and the Rosae Crucis. He referred to Jacob Boehme as his master in the art and law of divine wisdom.[44]

In New World Mystics, Dr. John Palo has a footnote indicating that William Penn visited Pietist conventicles in Europe. They were initiatic collegiums for Rosicrucians:

…he visited Pietist conventicles which were held in an air of great secrecy and danger of exposure. He invited the Rosae Crucis to settle on his land [in America]… These Pietists or Rosicrucians were thought unorthodox and hence undesirable in the eye of the politico-religious powers of Europe. They were accused of mixing Christian tenets with the practices of Ancient Egypt and some of the doctrines of Zoroaster.”

As explained by Dr. Palo, after Penn’s first trip to America in 1681, on several trips he made back to Europe, he had come into contact with individuals in England, Holland and Germany, who were playing an important role in executing a plan to establish a Rosicrucian colony in America by 1694. Notable among them were William Markham of the Philadelphic Society in London, who would serve later as Penn’s Deputy Governor of Pennsylvania, and Jacob Isaac Van Bebber, a German Rosicrucian, who later purchased a thousand acres of land from Penn for the purpose of establishing a colony in America. [45]

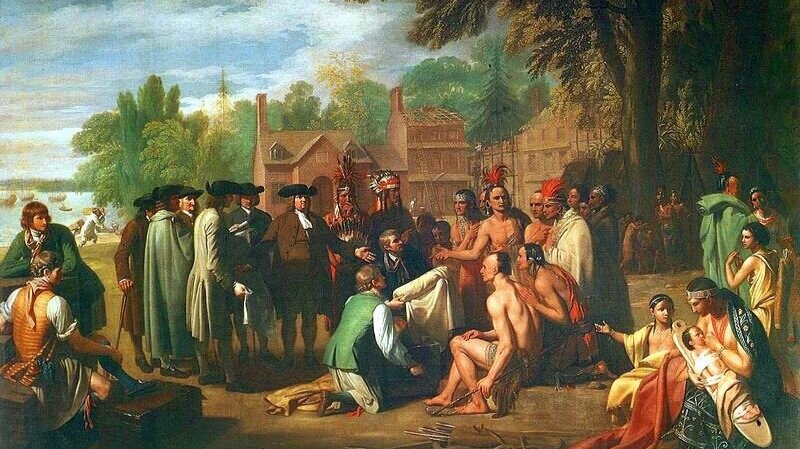

The Treaty of Penn with the Indians

In 1682, William Penn founded the city of Philadelphia, named after one of the “Seven Churches of Asia” mentioned in the Book of Revelation 3:10, as “the church steadfast in faith, that had kept God’s word and endured patiently.” Philadelphia played an instrumental role in the American Revolution as a meeting place for the Founding Fathers of the United States, who signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the Constitution in 1787. Philadelphia was one of the nation’s capitals during the Revolutionary War, and served as temporary US capital while Washington DC was under construction.

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693.

John Winthrop (1587 –1649)

John Winthrop (1587 – 1649) a wealthy English Puritan lawyer sailed across the Atlantic on the Arbella, leading to the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[46] Winthrop’s arrival signaled the beginning of the Great Migration. The term Great Migration usually refers to the migration in this period of English settlers, primarily Puritans to Massachusetts and the warm islands of the West Indies, especially the sugar rich island of Barbados, 1630–40. From 1630 through 1640 approximately 20,000 colonists came to New England. They came in family groups (rather than as isolated individuals) and were motivated chiefly by a quest for freedom to practice their Puritan religion. Winthrop’s noted words, a “City upon a Hill,” refer to a vision of a new society, not just economic opportunity.

On 12 June 1630, the Arbella led the small fleet bearing the next 700 settlers into Salem harbor. Salem may have inspired the city of Bensalem in Bacon’s New Atlantis, which was published in 1627. The settlement of Salem by Rosicrucians would explain the existence of witchcraft in the city, which would have given cause to the famous witch trials of 1692. Frances Yates notes that Dee’s influence later spread to Puritanism in the New World through John Winthrop’s son, John Winthrop, Jr., an alchemist and a follower of Dee. Winthrop used Dee’s esoteric symbol, the Monas Hieroglyphica, as his personal mark.[47] In 1628, to acquire the alchemical knowledge of the Middle East, Winthrop sailed to Venice and Constantinople, further extending his abilities and chemical contacts. Winthrop was famously eulogized Cotton Matther as “Hermes Christianus,” and praised as one who had mastered the alchemical secret of transmuting lead into gold.[48]

In Prospero’s America: John Winthrop, Jr., Alchemy, and the Creation of New England Culture (1606–1676), believes that, although less famous than his father, John Winthrop, Jr. was one of the most important figures in all of colonial English America, and describes how he used alchemy to shape many aspects of New England’s colonial settlement, and how that early modern science influenced an emerging Puritanism. Winthrop joined his father in New England in 1631. In the 1640s, Winthrop aimed to make New England a laboratory of alchemical transformation by founding a town he called “new London,” where alchemists could collaboratively pursue scientific advances in agriculture, mining, metallurgy, and medicine. Following the collapse of New England’s economy at the outbreak of the English Civil War, Winthrop returned to Europe from 1641 to 1643. While there, he was influenced by Samuel Hartlib and members of his circle, including John Dury and Jan Comenius. Dury as well was an active advisor and fundraiser for the Massachusetts Bay Colony, having also attempted to get Comenius appointed the first President of Harvard.[49]

Winthrop was also reputed to be Eirenaeus Philalethes, a pseudonymous author whose widely praised texts were then circulating in English alchemical circles. These works have been conclusively identified as the work of George Starkey (1628 – 1665), a young alchemist whom Winthrop helped train, and a devoted follower of van Helmont. Starkey reported to Hartlib that he was held under arrest in Massachusetts for two years under suspicion of being a Jesuit or a spy. Starkey emigrated to England in 1650, where he gained a significant reputation as an adept and influenced both Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton. Winthrop’s English connections to the Reverend John Everard (1584? – 1641), a Christian alchemist who was in touch with Robert Fludd. Winthrop’s interest in Everard was focused on determining whether or not he was a member of the Rosicrucians, with Winthrop finally determining he was not. Everard’s antinomian beliefs have led some scholars to speculate that Winthrop shared the same.[50]

In 1662, Winthrop travelled back to England, where he became a founding member of England’s Royal Society. His international scientific reputation, his connections among the members of the Royal Society, he gained extraordinarily generous terms for Royal Charter issued by Charles II, which united the colonies of Connecticut and New Haven, and gave the larger entity virtual political autonomy. Because of his alchemical reputation and medical knowledge, Winthrop was saught after as an expert in suspected witchcraft cases. First as a consultant, and later as the governor who presided over the trials, Winthrop imposed his interpretation of magic, by helping to steer accusations away from devil worship. As governor, and therefore also presiding judge and chief interrogator, he was able to engineer acquittals, such that Connecticut was transformed from New England’s harshest prosecutor of witchcraft, to a colony that never again hanged a person for the crime.[51]

Rev. George Phillips, the founder of the Congregational Church in America, arrived on the Arbella in 1630 with Governor Winthrop. In 1781, Phillips’s great-grandson, banker Dr. John Phillips, established Exeter Academy, a prestigious American private prep school in New Hampshire, and is one of the oldest secondary schools in the US. The Economist described the school as belonging to “an elite tier of private schools” in Britain and America that counts Eton and Harrow in its ranks. Exeter has a long list of famous former students, including Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Gore Vidal, Stewart Brand, Mark Zuckerberg, founder of Facebook, novelist John Irving, and Dan Brown the author of The Da Vinci Code and the Masonic-inspired The Lost Symbol.

Merrymount

A nineteenth-century engraving of Mayflower passenger Cpt. Miles Standish and his men observing the immoral behavior of the Maypole festivities of 1628.

Thomas Morton (c. 1579–1647)

Thomas Morton (c. 1579 – 1647), who maintained contacts with the School of Night, was an early American colonist from Devon, England, famed for founding the British colony of Merrymount, which was located in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts, and for his work studying Native American culture. In the late 1590s, Morton studied law at London's Clifford's Inn, where he was exposed to the “libertine culture” of the Inns of Court, where bawdy revels included Gesta Grayorum performances associated with Francis Bacon and Shakespeare. It is likely there that he met Ben Jonson, who would remain a friend throughout his life. Morton eventually settled into the service of Ferdinando Gorges, an associate of Sir Walter Raleigh, who was governor of the English port of Plymouth and a major colonial entrepreneur. Gorges had been part of Robert Devereux’s Essex Conspiracy, Essex's Rebellion was an unsuccessful rebellion led by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, in 1601 against Elizabeth I of England and the court faction led by Sir Robert Cecil to gain further influence at court. Gorges escaped punishment by testifying against the main conspirators who were executed for treason.

Gorges’ early involvement in the settlement of North America as well as his efforts in founding the Province of Maine in 1622 earned him the title of the “Father of English Colonization in North America,” even though Gorges himself never set foot in the New World.[52] Gorges had sought to undermine the legal basis for Puritan settlements throughout New England. In 1607, as a shareholder in the Plymouth Company, he helped fund the failed Popham Colony, in present-day Phippsburg, Maine. Just when the Pilgrims were trying to establish New Plymouth, an English war veteran named Ferdinando Gorges claimed that he and a group of investors possessed the only legitimate patent to create a colony in the region.[53] These financiers believed that they possessed a claim to all territory from modern-day Philadelphia to St. John, Newfoundland a point they emphasized in their charter. In 1622, Gorges received a land patent, along with John Mason, from the crown’s Plymouth Council for New England for the Province of Maine. In 1629, he and Mason divided the colony, with Mason’s portion south of the Piscataqua River becoming the Province of New Hampshire.

Morton would join forces with Gorges in his attempt to undermine the legal basis for the earliest English colonies in New England. By 1626, Morton had established a trading post at a place called Merrymount, on the site of modern-day Quincy, Massachusetts. Scandalous rumors spread of debauchery at Merrymount, including immoral sexual liaisons with native women and drunken orgies in honor of Bacchus and Aphrodite, or as the Puritan Governor William Bradford wrote in his history Of Plymouth Plantation, “They… set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing about it many days together, inviting the Indian women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together (like so many fairies, or furies rather) and worse practices. As if they had anew revived & celebrated the feasts of ye Roman Goddess Flora, or ye beastly practices of ye mad Bacchanalians.”[54]

Morton declared himself “Lord of Misrule,” of the Feast of Fools. As historians note, the name “Merrymount” can also refer to the Latin phrase Mas Maris meaning “erect phallus.”[55] On May 1, 1627, Merrymount decided to throw a party in the manner of Merrie Olde England. The Mayday festival, the “Revels of New Canaan,” inspired by “Cupid’s mother”—with its “pagan odes” to Neptune and Triton (as well as Venus and her lustful children, Cupid, Hymen and Priapus), its drinking song, and its erection of a huge 80-foot Maypole, topped with deer antlers—appalled the “Princes of Limbo,” as Morton referred to his Puritan neighbors. After a second Maypole party the following year, Myles Standish led a party of armed men to Merrymount, and arrested Morton. Morton returned to New England in 1629, where he wrote New English Canaan, that praised the wisdom and humanity of the Indians but mocked the Puritans, and made Morton a celebrity in political circles.[56]

The second 1628 Mayday, “Revels of New Canaan,” inspired by “Cupid’s mother.” with its “pagan odes” to Neptune and Triton as well as Venus and her lustful children, Cupid, Hymen and Priapus, its drinking song, and its erection of a huge Maypole, topped with deer antlers, again scandalized his Puritan neighbours, whom he referred to as “Princes of Limbo.” The Plymouth militia under Myles Standish took the town the following June with little resistance, chopped down the Maypole and arrested Morton. He was marooned on the deserted Isles of Shoals, off the coast of New Hampshire, where he was essentially left to starve. However, he was supplied with food by friendly natives from the mainland, and he eventually gained strength to escape to England. The Merrymount community survived without Morton for another year, but was renamed Mount Dagon by the Puritans, after the Semitic sea god. During the severe winter famine of 1629, residents of New Salem under John Endecott raided Mount Dagon’s corn supplies and destroyed what was left of the Maypole, denouncing it as a pagan idol and calling it the “Calf of Horeb.” To the disappointment of the Pilgrims, Morton faced no legal action back in England. Instead, he returned to New England in 1629, settling in Massachusetts just as Winthrop and his allies were trying to launch their new colony. Morton was rearrested, again put on trial and banished from the colonies. The following year the colony of Mount Dagon was burned to the ground and Morton again shipped back to England.

Barely surviving his harsh treatment during his journey into exile, he regained his strength in 1631, and after a short spell in an Essex jail, was released and began to sue the Massachusetts Bay Company, the political power behind the Puritans. To the surprise of Protestant English supporters of “Plymouther Separatists,” Morton won strong backing for his cause and was treated as a champion of liberty. With the help of his original backer, Ferdinando Gorges, he became the attorney of the Council of New England against the Massachusetts Bay Company. The real political force behind him, however, was the hostility of Charles I to the Puritan colonists. In 1635, Morton’s efforts were successful, and the Company’s charter was revoked. Major political rearrangements occurred thereafter in New England, though these were mainly due to colonial rejection of the court decision, subsequent isolation, lack of supplies and overpopulation, and increased conflict between foreign colonists and natives. Nonetheless, Plymouth became a place of woe, and many left Massachusetts for the relative safety of Connecticut.

After a short stint in jail in England, Morton was free again, and it was around this time that he began to conspire with Gorges. During the mid-1630s, Gorges pushed English authorities to recognize his claim to New England. His argument pivoted on testimony provided by Morton, who claimed that the Puritans had violated proper religious and governing practices. In 1637, Morton’s claims convinced King Charles I to make Gorges the royal governor of Massachusetts. In 1637, Morton published a book titled New English Canaan, in which he accused the English of genocide against the Native population and also of violating widely accepted Protestant religious practices. To make peace, the Puritans relented and in 1639 Gorges received the patent to modern-day Maine, which had been part of the original grant to the Massachusetts Bay Company. Gorges was declared the new Governor of the Colonies by Charles I, though he would never set foot in America. However, Morton’s success was cut short by the beginning of the English Civil War, which was triggered by agitation from the Puritans against Charles’s absolutism. In 1642, Morton planned to flee to New England with Gorges, but when Gorges mentor failed to make the trip, Morton returned alone as Gorges’ agent in Maine. Winthrop wrote that he lived there “poor and despised.”[57]

Anne Hutchinson (1591 – 1643) preaching in her house in Boston, 1637

Over the years, other rebels and free-thinkers have lived in Merrymount, which became Wollaston. The midwife Anne Hutchinson, who challenged the Puritan theocracy, lived there with her husband when they first arrived in New England in 1634. Hutchinson, who saw herself as a prophetess, became in involved in the Antinomian Controversy, which pitted John Winthrop and most of the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s Puritans against the Free Grace theology of her mentor John Cotton. John Hancock was born there, and John Quincy Adams, whose property in Quincy included the site of Mar-re Mount and who communicated to Thomas Jefferson his excitement upon finding a copy of New English Canaan after half a century.[66] Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story “The May-Pole of Merry Mount” in his Twice-Told Tales (1837) and J. L. Motley’s Merry Mount (1849) are based on Morton’s colonial career.

Return of Roger Williams from England with the First Charter from Parliament for Providence Plantations in July 1644

Hutchinson and many of her supporters established the settlement of Portsmouth with encouragement from Providence Plantations founder Roger Williams (1603 – 1683) in what became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Providence, the capital of Rhode Island and one of the oldest cities in the United States, was founded in 1636 by Williams, a Reformed Baptist theologian. As a Separatist, Williams considered the Church of England irredeemably corrupt and believed that one must completely separate from it to establish a new church for the true and pure worship of God. Williams was expelled by the Puritan leaders from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for spreading “new and dangerous ideas,” and he established the Providence Plantations in 1636 as a refuge offering what he called “liberty of conscience.”

New Amsterdam

Although many historians date American Jewish history to 1654 when a party of Jews arrived in New Amsterdam, later New York City, Jews have been a part of America’s history for far longer. The history of Jews in America dates to Christopher Columbus’s arrival in 1492, when Jews sailed on the first European transatlantic voyage. They also were among the first settlers in North America in the seventeenth century. Joachim Gaunse or Ganz, a Bohemian mining expert, became the first Bohemian and the first recorded Jew in colonial America when he landed on Roanoke Island in 1585. Sir Walter Raleigh had recruited Gaunse for an expedition to found a permanent settlement in the Virginia territory of the New World.[59] Gaunse and the other colonists later sailed back to England with Sir Francis Drake in 1586. Some historians have suggested that Gaunse was the model for the Jewish scientist Joabin in Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis.[60]

Another early Jewish visitor was Solomon Franco, a friend of Elias Ashmole and Stuart supporter who exercised an important influence in the development of Temple mysticism in Freemasonry, who traveled from Holland to the city of Boston in 1649.[61] Franco delivered supplies to Edward Gibbons, a major general in the Massachusetts militia, and an associate of the Rosicrucian John Winthrop, founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Gibbons emigrated from England to the Plymouth Colony in 1624 as an indentured servant to Thomas Morton. Edward had a change of heart and allied himself with the Puritans, joining the Salem Church in 1628.[62] After a dispute over who should pay Franco, Gibbons ruled that Franco was to be expelled from the colony, and he was forced to return to Holland. Although a Rabbi, in 1668 he converted to Anglicanism, publishing Truth springing out of the earth in the same year.[63]

Anne Hutchinson and many of her supporters established the settlement of Portsmouth with encouragement from Providence Plantations founder Roger Williams (1603 – 1683) in what became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Providence, the capital of Rhode Island and one of the oldest cities in the United States, was founded in 1636 by Williams, a Reformed Baptist theologian, As a Separatist, Williams considered the Church of England irredeemably corrupt and believed that one must completely separate from it to establish a new church for the true and pure worship of God. Williams was expelled by the Puritan leaders from the Massachusetts Bay Colony for spreading “new and dangerous ideas,” and he established the Providence Plantations in 1636 as a refuge offering what he called “liberty of conscience.” In 1639, Hutchinson split again from the group, and she, John Clarke (1609 –1676) and others moved to the south end of the island, establishing the town of Newport.

In September 1654, 23 Jews from Dutch Brazil arrived in New Amsterdam (later New York City).

Newport is the historic site to one of the oldest and most influential Jewish communities in early American history. In 1658, a group of Jews settled in Newport due to the official religious tolerance of the colony as established by Roger Williams. They were fleeing the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal but had not been permitted to settle elsewhere. The Newport congregation is now referred to as Congregation Jeshuat Israel and is the second-oldest Jewish congregation in the United States. Having being driven from Brazil, a number of Jews and their Rabbi, Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, an associate of Menasseh ben Israel, found their way to Jamaica which maintained regular trade with Newport. Having heard that there was an island the North where the “Mohommedan and the Jew” could worship freely, Aboab and fifteen Jewish families came to Newport.

Masonic historians have chosen to ignore evidence that a Masonic initiation took place among this group, long before the formal establishment of Masonic lodges there. According to Samuel Oppenheim, “Jews may be said to have had the honor of being among the first, if not the first, to work the degrees of Masonry in this country, by bringing these with them on their arrival in Rhode Island in 1658.”[64] Nathan H. Gould, a 33º degree Mason, who had been Master of St. John’s Lodge of Newport in 1857, discovered a document that recorded a meeting of Jewish Masons in Newport in 1658: “wee mett att y House of Mordecai Campunall and affter Synagog Wee gave Abm Moses the degrees of Maconrie.” They brought with them the three first degrees of Freemasonry, which they worked in the house of Campannall, as they and their successors continued to do so until the year 1742.[65]

The Jewish arrival in New Amsterdam in 1654 was the first organized Jewish migration to North America. Overseas, Jewish settlers became involved in slavery in Holland’s colonies, beginning in Brazil. Seized by the Dutch West India Company from Portugal in 1630, Brazil attracted a large number of Jewish settlers. By the middle of the 1640s, approximately 1,500 Jewish inhabitants lived in the areas of northeastern Brazil controlled by the Dutch. There they established two congregations. These included the congregation of Zur Israel in Recife, headed by Isaac Aboab da Fonseca, the first American rabbi, who had been replace in Amsterdam by Menasseh ben Israel. Their numbers began to decline in 1645 when the Portuguese colonists rose up in rebellion, raising the threat of renewed control by Portugal and the return of the Inquisition. Nine years later, in 1654, a Portuguese expeditionary force recaptured Recife, forcing the Dutch to abandon Brazil. When the Dutch departed, the remaining Jewish population, approximately 650 in number, also left, some returning to Holland and others emigrating to the Dutch colony at New Amsterdam or to the English one in Barbados.[66]

The first Jewish settler in New Amsterdam was Jacob Barsimson, who arrived in 1654, in the ship Pear Tree. Barsimson had been sent out by the Jewish leaders of Amsterdam to determine the possibilities of an extensive Jewish immigration to New Amsterdam. He was followed in the same year by a party of 23 Sephardic Jews, refugees of families fleeing persecution by the Portuguese Inquisition after the conquest of Recife, Brazil. According to account in Saul Levi Morteira and David Franco Mendes, they were then taken by Spanish pirates for a time, were robbed, and then blown off course and finally landed in New Amsterdam.[67] Some returned to Curaçao while others to Amsterdam, including two associates of Menasseh ben Israel, Isaac Aboab de Fonseca of Zur Israel, the first American rabbi, and Moses de Aguilar, the first American cantor, who both went on to become followers of Sabbatai Zevi.[68]

In Cuba, the Jews eventually boarded the St. Catrina, called by later historians the “Jewish Mayflower,” which took them to New Amsterdam.[69] Director-General Peter Stuyvesant (1592 – 1672) of the Dutch West India Company refused to allow the permanent settlement, as he wrote to the Amsterdam Chamber of the Dutch West India Company in 1654, he hoped that “the deceitful race,—such hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ,—be not allowed to further infect and trouble this new colony.”[70] Stuyvesant’s decision was again rescinded after pressure from the directors of the Dutch West India Company, which had several significant Jewish investors.[71] The Company’s response to Stuyvesant was that such action “would be unreasonable and improper, especially in view of the big losses which this nation suffered from the conquest of Brazil and in view of the great fortune which they have invested in the company.”[72] In 1654, the new community founded Congregation Shearith Israel, the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States.

The Jews in New York traded with a Jewish network that spanned to the Caribbean, including the islands Curaçao, Surinam, Saint Thomas, Barbados, Madeira and Jamaica, the principal trading ports for New York outside of England. According to Stanley Feldstein, “Since the West Indian trade was a necessity to America’s economy and since this trade was, in varying degrees, controlled by Jewish mercantile houses, American Jewry was influential in the commercial destiny of Britain’s overseas empire.”[73] Shortly after their settlement, regular trade was established between the Jews of New Amsterdam and Curaçao, contributing to the commercial development of both colonies.[74] Curaçao was considered “the mother of American Jewish communities.”[75] The first Jew to settle in Curaçao was a Dutch-Jewish interpreter named Samuel Cohen, who arrived in 1634. In 1659 the Dutch West India Company gave Isaac d’Acosta of Amsterdam privileges to bring Jewish colonists to Curacao.[76] There they founded Congregation Mikve Israel-Emanuel, named after Menasseh ben Israel’s Hope of Israel (“Mikveh Israel”), and the oldest continuously used synagogue in the Americas.

A Slave Auction In Virginia

In 1659, Stuyvesant had complained to the directors of the Company that Jews in Curaçao were allowed to hold African slaves, and were granted other privileges not enjoyed by other colonists of New Netherlands, and he demanded for his own people “if not more, at least the same, privileges” as were enjoyed by the “usurious and covetous Jews.”[77] The Dutch West India Company achieved its goal by 1648 of establishing Curaçao as the largest slave center of the Caribbean.[78] Jewish businessmen, who owned 80 percent of the Curaçao plantations, facilitated the transportation of the slaves from Curaçao to the Spanish American.[79]

In 1664, New Amsterdam was captured by the British, who had previously barred Jews from settling in their colonies. Oliver Cromwell lifted the prohibition, and founding of the first major Jewish settlement soon followed in Newport. Religious tolerance was also established elsewhere in the colonies. Sephardic Dutch Jews were also among the early settlers of Newport, Savannah, Philadelphia and Baltimore. Most of the early colonists in North America were of Sephardic stock, and came from Brazil, West Indies, Portugal, and Holland.[80] During the mid-1700s, Charleston was the preferred destination of Jewish émigrés from London, who represented numerous wealthy merchant families. South Carolina was originally governed under an elaborate charter drawn up in 1669 by the English philosopher John Locke, a member of the Lantern of Benjamin Furly. This charter granted liberty of conscience to all settlers, expressly mentioning “Jews, heathens, and dissenters.” In 1740, to regularize and encourage immigration, British Parliament passed the Plantation Act, which specifically permitted Jews and other nonconformists to be naturalized in their American colonies. The colony’s first synagogue, Congregation Beth Elohim, founded in 1749, is one of the oldest Jewish congregations in the United States.[81]

Prince Rupert (1619 – 1682) with his elder brother, Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine (1617 – 1680), sons of Frederick V of the Palatinate (grandson of William the Silent) and Elizabeth Stuart

Savannah became the third oldest Jewish congregation in the United States. Forty-two Jews, the “largest group of Jews to land in North America in Colonial days” arrived in Savannah in 1733, just five months after the colony of Georgia was established by General James Edward Oglethorpe (1696 – 1785), who had conducted business with the Franks.[82] Jews were significant investors in Oglethorpe of the Royal African Company (RAC) which was directed by Oglethorpe.[83] The RAC was an English mercantile company set up in 1660 by the royal Stuart family and City of London merchants to trade along the west coast of Africa. It was led by the Duke of York, the brother of Charles II, who later became James II. It shipped more African slaves to the Americas than any other institution in the history of the Atlantic slave trade.

Although it was originally established to exploit the gold fields up the Gambia River, which were identified by Prince Rupert (1619 – 1682) during the Interregnum, it soon developed and led a brutal and sustained slave trade.[84] Prince Rupert was the son of Frederick V of the Palatinate and Elizabeth Stuart of the Alchemical Wedding, and a founding member of the Royal Society. Following the Restoration, Rupert became the head of the Royal Navy. As a colonial governor, Rupert shaped the political geography of modern Canada: Rupert's Land, a territory in British North America comprising the Hudson Bay drainage basin, in which a commercial monopoly was operated by the Hudson’s Bay Company which he founded.

A view of Savannah, Georgia (1734)

All but eight of the Jews who first settled in Savannah were Spanish and Portuguese Jews, who had fled to England a decade earlier to escape the Spanish Inquisition. In London, many had been members of the Bevis Marks Synagogue. That year they founded Congregation Mickve Israel of Savannah, one of the oldest synagogues in the United States, and which remains today an active spiritual community, affiliated with the Reform movement in Judaism. Savannah Jews have been prominent in all aspects of the commercial, cultural and political life of the community.[85]

The Congregation was the first Jewish community to receive a letter from the President of the United States. In response to a letter sent by Levi Sheftall, the congregation’s president, congratulating George Washington on his election as the first President, Washington replied, “To the Hebrew Congregation of the City of Savannah, Georgia:” “…May the same wonder-working Deity, who long since delivering the Hebrews from their Egyptian Oppressors planted them in the promised land—whose providential agency has lately been conspicuous in establishing these United States as an independent nation—still continue to water them with the dews of heaven and to make the inhabitants of every denomination participate in the temporal and spiritual blessings of that people whose God is Jehovah.”[86]

[1] Edward Gaylord Bourne. “The Naming of America.” The American Historical Review, Vol. 10, No. 1 (October, 1904), p. 50.

[2] Patricia U. Bonomi. Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America (Oxford University Press, 1988).

[3] Manly P. Hall. The Secret Destiny of America (Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society, 1944).

[4] Albert Pike. Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (Charleston: Southern Jurisdiction of Scottish Rite Freemasonry, 1871).

[5] Israel Regardieo. A Garden of Pomegranates: Skrying on the Tree of Life (St. Paul, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications, 2004) p. 489.

[6] Aleister Crowley. Magick Without Tears, “Letter C.” (New Falcon Publications, 1991)

[7] Éliphas Lévi. Transcendental Magic: its Doctrine and Ritual. Arthur Edward Waite (trans.) ([Rev. ed.] ed.) (London: Rider, 1968).

[8] Manly P. Hall. The Lost Keys to Freemasonry, (Macoy Publishing and Masonic Supply Company, Inc., Richmond, Virginia, 1976), p.48.

[9] Albert Gallatin Mackey. An encyclopædia of freemasonry and its kindred sciences (Philadelphia: Moss & Company, 1879), p. 804.

[10] Arthur Edward Waite. A New Encyclopædia of Freemasonry (ars Magna Latomorum) and of Cognate Instituted Mysteries: Their Rites, Literature and History, Volume 2 (W. Rider and Son, 1921), p. 487.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Scottish Rite Journal (September, 1990).

[14] Frederick A. Ober. Amerigo Vespuci (New York: Harper Brothers, 1907), p. 28.

[15] Åkerman. Rose Cross over the Baltic, p. 17.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “The Fortunate Isles.” Mapping the Fantastic (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.beccajjones.com/the-fortunate-isles/

[18] G. H. Turnbull. “Samuel Hartlib’s Influence on the Early History of the Royal Society.” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Apr., 1953), pp. 103.

[19] Dickson. The Tessera of Antilia, p. 118.

[20] Paul Toscanelli’s 1474 letter to the Spanish Court, RA Skelton, “Explorers’ Maps: Chapters in the Cartographic Record of Geographical Discovery.”

[21] Peter Martyr d’Anghiera. De Orbe Novo, 1511–1125 https://www.gutenberg.org/etext/12425

[22] Chloë Houston. The Renaissance Utopia: Dialogue, Travel and the Ideal Society (New York: Routledge, 2014), p. 138.

[23] Yates. Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 169.

[24] Patrick Collinson. “Truth, lies and fiction in sixteenth-century Protestant historiography.” The Historical Imagination in Early Modern Britain: History, Rhetoric, and Fiction, 1500-1800. ed. Donald R. Kelley, David Harris Sacks (Cambridge University Press, 1991).

[25] Ibid.

[26] Charles Bowie Millican. Spenser and the Table Round, (New York: Octagon, 1932).

[27] Yates. The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, p. 90.

[28] “The Enochian Apocalypse,” in Richard Metzger. Book of Lies: The Disinformation Guide to Magick and the Occult (second ed.) (Newburyport, Massachusetts: Red Wheel/Weiser/Conari, 2008),

[29] Virginia Hewitt, “Britannia” (fl. 1st–21st cent.)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, Sept 2004).

[30] Michael Howard. “The British Occult Secret Service.” New Dawn, (May 10, 2008).

[31] Ibid.

[32] Leon M. Zeldis. “An Episode of Piracy” (1962).

[33] The History of the World (New YorK: B. Franklin, 1829) Chap. XI, p. 385.

[34] Cited in Manly P. Hall. America’s Assignment with Destiny (The Philosophical Research Society, 1951), p. 69– 70.

[35] Nicholas Hagger. The Secret Founding of America.

[36] La vie d’un exploer (Paris: Laperouse, 1625) cited in Graham Philips, Merlin and the Discovery of Avalon in the New World (Rochester, Vermont: Bear & Company, 2011).

[37] C. Oman. The Winter Queen (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1938), ch. 50; cited in Graham Phillips. Merlin and the Discovery of Avalon in the New World (p. 169) (Inner Traditions/Bear & Company). Kindle Edition.

[38] Du Gua’s autobiography survives in two volumes in La vie d’un exploer (Paris: Lapérouse, 1626). Cited in Graham Phillips. Merlin and the Discovery of Avalon in the New World (Inner Traditions/Bear & Company. Kindle Edition).

[39] Frederick Samuel Boas. Christopher Marlowe: a biographical and critical study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940).

[40] D. Simmons. Henri of Naverre (London: Blakewell, 1941), p. 67–78.

[41] Ibid., p. 103.

[42] Julius Friedrich Sachse. The German Pietists of Provincial Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, 1895; New York, 1970 [reprint]), p. 258.

[43] ‘doctissimus Astrologus, Magus et Cabbalista’, cited in Levente Juhász, “Johannes Kelpius (1673–1708): Mystic on the Wissahickon,” in M. Caricchio, G. Tarantino, eds., Cromohs Virtual Seminars. Recent historiographical trends of the British Studies (17th-18th Centuries), 2006-2007: 1-9.

[44] “What Roles did Francis Bacon and Other Notable Rosicrucians Play in American Colonial Activity and the Establishment of a Democratic Republic?” Group Pictorial Presentation at The Queen Mary (Long Beach, Cambridge Analytica, 1984).

[45] Linda S. Schrigner, et al. Bacon’s “Secret Society” – The Ephrata Connection: Rosicrucianism in Early America (1983)

[46] Yates. The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, p. 226.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Neil Kamil. Fortress of the Soul: Violence, Metaphysics, and Material Life in the Huguenots' New World, 1517-1751 (JHU Press, 2020), p. 243.

[49] J.C. Laursen & R.H. Popkin. “Introduction.” In Millenarianism and Messianism in Early Modern European Culture, Volume IV, ed. J.C. Laursen & R.H. Popkin (Springer Science+Business Media, 2001), p. xvii.

[50] “Winthrop, John, Jr.” Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com (January 25, 2022). Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/winthrop-john-jr

[51] Walter W. Woodward. “John Winthrop, Jr., and the Alchemy of Colonial Settlement.” American Ancestors (Spring 2011), p. 30.

[52] J.K. Laughton. “Gorges, Sir Ferdinando.” In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. 22 (New York: Macmillan and Co. 1890), p. 241; Miller Christy. “Attempts toward Colonization: The Council for New England and the Merchant Venturers of Bristol, 1621-1623.” American Historical Review. 4 (4): 1899, p. 683.

[53] Peter Mancall. “The two men who almost derailed New England’s first colonies.” The Conversation (November 21, 2016). Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/the-two-men-who-almost-derailed-new-englands-first-colonies-68213

[54] “The Maypole That Infuriated the Puritans.” New England Historical Society (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/maypole-infuriated-puritans/

[55] Thomas Morton. New English Canaan. ed. Jack Dempsey (Stoneham, MA: Jack Dempsey, 2000), p. 134, n. 446.

[56] “The Maypole That Infuriated the Puritans.”

[57] Peter Mancall. “The two men who almost derailed New England’s first colonies.”

[58] David A. Lupher “Thomas Morton of Ma-re Mount: The ‘Lady of Learning’ versus ‘Elephants of Wit’.” Greeks, Romans, and Pilgrims (Leiden: Brill, 2017), p. 82.

[59] Gary C. Grassl. “Joachim Ganz of Prague: The First Jew in English America.” American Jewish Historical Society Quarterly Publication, Vol. 86, No. 2.

[60] Lewis S. Feuer, (1982). “Francis Bacon and the Jews: Who was the Jew in the ‘New Atlantis’?” Jewish Historical Studies. 29: 1–25.

[61]. D. Stevenson. Origins, 219-20; C.H. Josten. Elias Ashmole (Oxford: Clarendon, l966), I, 92; II, 395-96, 609. On seventeenth-century ambulatory military lodges, see John Herron Lepper, “`The Poor Common Soldier,’ a Study of Irish Ambulatory Warrants,” Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, 38 (l925), 149-55.

[62] “Edward Gibbons.” The Great Allotment: Pullen Point’s First Land Owners. Retrieved from https://winthropmemorials.org/great-allotment/pages/edward-gibbons.html

[63] Solomon Franco. Truth springing out of the earth (London: John Williams, 1670).

[64] Samuel Oppenheim. “The Jews and Masonry in the United States Before 1810.” American Jewish Historical Quarterly, Vol 19 (1910).

[65] Ibid.

[66] Eli Faber. Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade: Setting the Record Straight (New York University, 1998), p. 16.

[67] “The Number of Jews in Dutch Brazil.” Jewish Social Studies, 16 (1954), p. 107‑114.

[68] Gil Stern Zohar. “Jewish pirates of the Caribbean.” Jerusalem Post (April 9, 2016); Meyer Kayserling. “AGUILAR (AGUYLAR), MOSES RAPHAELDE.” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[69] Leo Hershkowitz. “By Chance or Choice: Jews in New Amsterdam 1654.” American Jewish Archives, 57 (2005), p. 1–13.

[70] Matthew Frye Jacobson. Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race (Harvard University Press, 1999), p.17.

[71] Faber. Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade.

[72] Marcus Arkin. Aspects of Jewish Economic History (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1975), pp. 353

[73] Stanley Feldstein. The Land That I Show You (New York: Anchor Press/ Doubleday, 1978), p. 13.

[74] Cyrus Adler & Herbert Friedenwald. “Curacao.” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[75] Seymour B. Liebman. New World Jewry, 1493–1825: Requiem for the Forgotten (New York: KTAV, 1982), p. 179.

[76] Ariel Scheib. “Curaçao.” Jewish Virtual Library.

[77] Cyrus Adler & Herbert Friedenwald. “Curacao.” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[78] Isaac S. & Susan A. Emmanuel. History of the Jews of the Netherland Antilles (Cincinnati: American Jewish Archives, 1973), p. 75; Johan Hartog. Curaqao From Colonial Dependence to Autonomy (Aruba, Netherland Antilles, 1968), pp. 101-2.

[79] Marc Lee Raphael. Jews and Judaism in the United States: a Documentary History (New York: Behrman House, Inc., 1983), p. 24.

[80] Cyrus Adler & A. W. Brunner. “America.” Jewish Encyclopedia.

[81] Nell Porter Brown. “A ‘portion of the People’.” Harvard Magazine, (January–February 2003).

[82] William Pencak. “Jews and Anti-Semitism in Early Pennsylvania” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 126, No. 3 (July, 2002), p. 370.

[83] Faber. Jews, Slaves, and the Slave Trade.

[84] Jesus College Cambridge Legacy of Slavery Working Party (November 25, 2019). Jesus College Legacy of Slavery Working Party Interim Report (July-October 2019) (Report). pp. 9–10.

[85] B.H. Levy & Rabbi Arnold Mark Belzer. “Savannah, Georgia.” Virtual Jewish World.

[86] George Washington to Savannah, Georgia, Hebrew Congregation, May, 1790, George Washington Papers at The Library of Congress.

Volume Two

The Elizabethan Age

The Great Conjunction

The Alchemical Wedding

The Rosicrucian Furore

The Invisible College

1666

The Royal Society

America

Redemption Through Sin

Oriental Kabbalah

The Grand Lodge

The Illuminati

The Asiatic Brethren

The American Revolution

Haskalah

The Aryan Myth

The Carbonari

The American Civil War

God is Dead

Theosophy

Shambhala