15. The Esalen Institute

Human Potentials

LSD evangelist Timothy Leary confessed, “I give the CIA total credit for sponsoring and initiating the entire consciousness movement, counterculture events of the 1960s”[1] However, as most studies of the sixties agree, the idealism of the decade died with two events: the Manson murders and a tragedy that was showcased in a film called Gimme Shelter, about the Altamont Free Concert. Meredith Hunter, a young African-American man, was stabbed to death by members of the Hell’s Angels, in front of the stage while the Rolling Stones played “Sympathy for the Devil.” Manson had contacted a number of religious groups, including the OTO, the Process Church, the Church of Scientology, and the Esalen Institute, which he visited at the same time as his victims Sharon Tate and Abigail Folger, who were its frequent visitors, just days before his followers murdered them on August 8–9, 1969.[2]

As Michael Rossman wrote in The Wedding Within the War, his memoir of the 1960s, it seemed that the energy unleashed at Berkeley was beginning to turn, not right or left, “but into… something else, without a name.”[3] Given Manson’s interest in Esalen, Bill Ellis remarked, “Occultism, LaVey’s Church of Satan, and the counterculture, inevitably, had become linked to pop Satanism and blood crimes.”[4] “In 1968,” one of Esalen’s founding figures recalled four decades later:

Esalen was the center of the cyclone of the youth rebellion. It was one of the central places, like Mecca for the Islamic culture. Esalen was a pilgrimage center for hundreds and thousands of youth interested in some sense of transcendence, breakthrough consciousness, LSD, the sexual revolution, encounter, being sensitive, finding your body, yoga—all of these things were at first filtered into the culture through Esalen. By 1966, ’67, and ’68, Esalen was making a world impact.[5]

As admitted by Michael Murphy, one of its founders, one of the models for the development of Esalen Institute was the Eranos Conferences, founded by Olga Froebe-Kapteyn, a devotee of Alice Baily, and funded by the Mary and Paul Mellon, of the influential Mellon family, who shared a friendship to Carl Jung with Allen Dulles, who all worked with the OSS during World War II.[6] According to Wouter Hanegraaff in New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought, in addition to the hippies, Esalen had been the second major influence of the 60s counterculture and the rise of the New Age movement.[7] As Jay Stevens explained in Storming Heaven: LSD & The American Dream, “It was no accident that the group leaders at Esalen’s first public seminar were all veterans of the psychedelic movement.”[8] Closely connected with mystical experimentation, aimed at achieving new states of consciousness within the New Age, was the use of drugs, believed to produce a shamanistic experience. Jeffrey Kripal, author of Esalen: The Religion of No Religion, points out that Huxley’s discussions of Tantra and the mystical possibilities of psychedelics, and what he called the “perennial philosophy,” were foundational at Esalen.

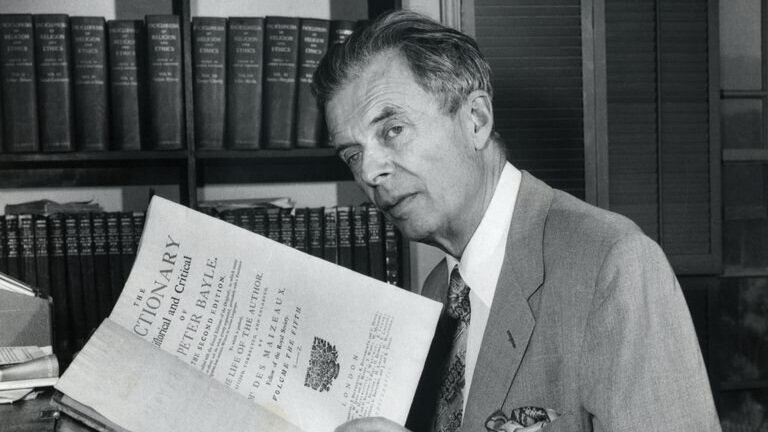

Aldous Huxley

Gerald Heard, Christopher Isherwood, Swami Prabhavananda

In 1937, Huxley moved to Hollywood with his wife Maria, son Matthew and friend Gerald Heard. In 1938 Huxley befriended Jiddu Krishnamurti whose teachings he greatly admired. After Annie Besant’s death, Huxley and Krishnamurti, along with Guido Ferrando, and Rosalind Rajagopal, built the Happy Valley School in California, now renamed the Besant Hill School of Happy Valley in her honor. Beginning in 1939 and continuing until his death in 1963, Huxley had an extensive association with the Vedanta Society of Southern California, founded and headed by Swami Prabhavananda, of the Ramakrishna Order founded by Vivekananda and his master Ramakrishna. Vivekananda attracted several followers and admirers such as William James, Nikola Tesla, Sarah Bernhardt, Nicholas and Helena Roerich, among many others. Prabhavananda as well was able to attract an illustrious following which included Igor Stravinsky, Laurence Olivier, Vivien Leigh and W. Somerset Maugham, which led to his writing The Razor’s Edge in 1944. Together with Heard, Isherwood, Huxley and other followers were initiated as well by Prabhavananda and taught meditation and other mystical Hindu practices.

Inspired by the universalist teachings of Vivekananda, as well as Sir John Woodroffe (Arthur Avalon), Huxley set out to translate Indian ideas into Western literary and intellectual culture with the writing of The Perennial Philosophy (1945), an anthology of short passages taken from traditional Eastern texts and the writings of Western mysticism. Huxley’s book insists on the truth of the occult, suggesting that there are realities beyond the generally accepted “five senses.” “Perennial Philosophy” is another name for prisca theologia of the Renaissance mystics or the Traditionalism developed by René Guénon. Mirroring the teachings of Guénon, who is quoted in the book, Huxley explains: “rudiments of the Perennial Philosophy may be found among the traditionary [sic] lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions.”[9] Huxley relates that the doctrine that God can be incarnated in human form is found in most of the principal historic expositions of the Perennial Philosophy in Hinduism, in Mahayana Buddhism, in Christianity and among the Sufis.

Gregory Bateson, original member of the Cybernetics Group, and who recommended the founding of the CIA.

Esalen’s goal was to assist in the coming transformation by exploring work in the humanities and sciences, in order to fully realize what Aldous Huxley had called the “human potentialities.” Esalen thus represented a fruition of the Human Potential Movement (HPM), whose founding has often been attributed to Gurdjieff, and which arose in the 1960s around the concept of cultivating the extraordinary potential that its advocates believed to lie largely untapped in all people. The movement took as its premise the belief that through the development of this “human potential” humans could experience an exceptional quality of life filled with happiness, creativity and fulfillment. According to Kripal, Huxley’s call for an institution that could teach the “nonverbal humanities” and the development of the “human potentialities” functioned as the working mission statement of early Esalen, and Huxley offered lectures on the “Human Potential” at Esalen in the early 1960s.[10]

Michael Murphy and Richard Price

The Esalen Institute was established in 1962, in Big Sur, California, by two transcendental meditation students, Michael Murphy and Richard Price, who were given networking support by Alan Watts, Aldous Huxley and his wife Laura, as well as by Gerald Heard and Gregory Bateson. Price’s interest in the expansion of human potential led him to investigate many avenues of research, including the exploration of altered states of consciousness with psychedelic drugs, and participating in experiments at Gregory Bateson’s Palo Alto Veterans Hospital.[11] Richard Price’s father, Herman Price (anglicized from Preuss) was born into an Eastern European Jewish family in 1895. Price graduated in 1952, with a major in psychology from Stanford University, where he studied with both Gregory Bateson and Frederic Spiegelberg, a speaker at Eranos and friend of Watts, who would both later be pivotal influences in the founding and development of Esalen. After graduating, Price attended Harvard University to continue studying psychology, and then joined the Air Force and was given an assignment in San Francisco.

In 1956, in San Francisco, Price experienced a transformative psychotic break and was admitted to a mental hospital for a time. In May 1960, Price returned to San Francisco where he met Michael Murphy, also a graduate of Stanford University. Moving to San Francisco placed Price at the center of the emerging North Beach Beat scene, where he became involved with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder in particular.[12] Ginsberg had been experimenting with drugs since the 1940s as a way of achieving what he and his friends named the “New Vision,” methodically keeping lists of the drugs he sampled. He experimented with morphine with Burroughs, and marijuana with fellow jazz fans. Ginsberg and the other Beat writers had also been experimenting with peyote and ayahuasca as far back as the early 1950s.

Before also settling in San Francisco, Murphy traveled to India to study with Sri Aurobindo. In the mid-1960s, Aurobindo’s close spiritual collaborator, known as The Mother, who had studied with Max Theon, personally guided the founding of Auroville, an international township endorsed by UNESCO to further human unity in Tamil Nadu, near the Pondicherry border in southern India, which was to be a place “where men and women of all countries are able to live in peace and progressive harmony above all creeds, all politics and all nationalities.” Price took a room in San Francisco at Watts’ and Spiegelberg’s newly founded American Academy of Asian Studies.

In 1962, a month after he had introduced Leary to “the ultimate yoga” of Tantra, and just two months after he met Michael Murphy and Richard Price in Big Sur, Huxley published his very last novel, Island, a celebration of Tantric eroticism.[13] Reflecting this interest in both subjects, Leary, a regular at Esalen, believed he discovered the sexual potential of LSD “to realize that God and Sex are one, that God for a man is woman, that the direct path to God is through the divine union of male-female.”[14] Huxley explained to Leary that Tantra is the highest ideal possible, and linking it to Zen Buddhism and interpreting it in terms of psychotherapy and gestalt therapy, and said that “LSD and the mushrooms should be used, it seems to me, in the context of this basis Tantrik idea of the yoga of total awareness, leading to enlightenment within the world of everyday experience—which of course becomes the world of miracle and beauty and divine mystery when experience is what it always ought to be.”[15]

Esalen Institute, Big Sur, California

Murphy and Price’s goal at Esalen was to assist in the coming transformation by exploring work in the humanities and sciences, in order to fully realize what Aldous Huxley had called the “human potentialities.” Esalen thus represented a fruition of The Human Potential Movement (HPM), whose founding has often been attributed to Gurdjieff. This new outlook was based on rebranding Mesmer’s approach to hypnotism to accommodate modern prejudices against the occult, so that it came instead to be viewed as a method to “untap” the hidden resources of the mind. At the deepest level, subjects of hypnosis described experiences almost identical to ones undergone by those under the influence of psychedelic drugs. According to Fuller Torrey:

At this deepest level of consciousness, subjects feel themselves to be united with the creative principle of the universe (animal magnetism) There is a mystical sense of intimate rapport with the cosmos. Subjects feel that they are in possession of knowledge which transcends that of physical, space-time reality. Those who enter this state are able to use it for diagnosing the nature and causes of physical illness. They are also able to exert control over these magnetic healing energies so as to cure persons even at a considerable physical distance. Telepathy, cosmic consciousness, and mystical wisdom all belong to this deepest level of consciousness discovered in the mesmerists’ experiments.[16]

These “deeper” levels of consciousness were therefore perceived to open the individual to qualitatively “higher” planes of mental existence.[17] As indicated by Martin and Deidre Bobgan in Hypnosis: Medical, Scientific, or Occultic?:

They believed that these powers could be used to understand the self, to attain perfect health, to develop supernatural gifts, and to reach spiritual heights. Thus, the goal and impetus for discovering and developing human potential grew out of mesmerism and stimulated the growth and expansion of psychotherapy, positive thinking, the human potential movement, and the mindscience religions, as well as the growth and expansion of hypnosis itself.[18]

As explained by Hans Thomas Hakl in Eranos: An Alternative Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century, “Spiegelberg not only lectured at Esalen, as also did the Eranos speaker Paul Tillich, the historian Arnold Toynbee or the parapsychologist J.B. Rhine, but he also steered Esalen’s founder, Michael Murphy, on to the spiritual path that would lead him to Esalen.”[19] At Esalen, Murphy and Price hosted a lineup of speakers that effectively also mirrored the list of New Age influencers identified in the survey that was the basis of Marilyn Ferguson’s Aquarian Conspiracy. These included B.F. Skinner, Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, Gregory Bateson and Carlos Castaneda. The more famous guests of Esalen would also include mystically inclined scholars like Carl Sagan, Fritjof Capra, as well as astronauts and Apple executives, Christie Brinkley and Billy Joel, Robert Anton Wilson, Uri Geller, Erik Erikson, as well as numerous countercultural icons including Joan Baez (a former girlfriend of Steve Jobs), Hunter S. Thompson and Timothy Leary.

Bollingen Press

Joseph Campbell (1904 – 1987), most well-known work is his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), in which he discusses his theory of the journey of the archetypal hero, his interpretation of the dying-god

Mary and Paul Mellon

When Leary had inquired about Tantra from Huxley, he recommended to him the works of Sir John Wooddroffe (aka Arthur Avalon), Mircea Eliade, and Heinrich Zimmer’s chapter on Tantra in Philosophies of India, ghostwritten by the mythologist Joseph Campbell. Campbell first became interested in oriental religions after a meeting in 1924 with Jiddu Krishnamurti, the former protégé of the Theosophical Society President Annie Besant, who had seen him as the future World Teacher. In 1931–1932, Campbell became close friends with author John Steinbeck and his wife Carol, with whom he had an affair.[20] Campbell, like John Steinbeck, fell under the influence of the marine biologist Ed Ricketts, who was the model for central characters in several of Steinbeck’s novels including Cannery Row. Campbell lived next door to Ricketts for a while, and accompanied him, along with Xenia and Sasha Kashevaroff, on a 1932 journey to Juneau, Alaska.[21] Xenia, an American surrealist sculptor, married John Cage in 1935. They divorced in 1945 when a ménage à trois with Merce Cunningham became a private affair between the two men; Cage and Cunningham were together until Cage’s death.[22]

Campbell also helped Swami Nikhilananda with the translation of the Upanishads and a book about Ramakrishna. At the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda center in New York he came to know Heinrich Zimmer, one of the founding personalities of Eranos. Through Zimmer, Campbell was introduced to the Tarot cards, and much later wrote an article on the symbolism of the so-called Marseilles Tarot. Campbell’s interest in esoteric studies was also expressed in his interest with the Grail mythos. After Zimmer’s death, Campbell took care of his literary estate, which he organized with the advice from Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, René Guénon’s leading student.

Campbell edited the first papers from Jung’s annual Eranos conferences, where he was an attendee. Campbell helped Mary Mellon, the original sponsor of the Eranos conferences, found Bollingen Series of books on psychology, anthropology and myth. Mary was the wife of Paul Mellon. Most prominent among the Mellon family supporters of the American Liberty League was Paul’s father, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon and a supporter of Hitler.[23] Paul was co-heir to one of America’s greatest business fortunes, derived from the Mellon Bank, and served with Allen Dulles in the OSS in Europe during World War II. Paul’s sister Ailsa Mellon Bruce was married to David Bruce, also a former OSS officer and later US ambassador to Great Britain. Andrew’s brother, James Ross Mellon, was the great-grandfather of William Mellon Hitchcock, who funded Leary’s LSD projects at the family’s Millbrook Estate.[24] Hitchcock was sent by his uncle by marriage, David Bruce, to meet with Dr. Stephen Ward to investigate the rumors of Masonically-themed “black magic” parties connected to the Profumo Affair.[25]

Mircea Eliade, former Ur Group member with Julius Evola

When Paul Mellon once complained to the essayist and poet Allen Tate that too many writers were leftists, Tate replied that writers were typically in financial need and that Mellon should award scholarships and prizes, which would inhibit the revolutionary spirit. Mellon, as the story goes, then founded the Bollingen-Mellon prizes of twenty thousand dollars each.[26] In 1948, the foundation made an endowment to the Library of Congress to be used toward a Bollingen Prize for the best poetry each year. The Library of Congress fellows, who in that year included T.S. Eliot, W. H. Auden and Conrad Aiken, gave the 1949 prize to Ezra Pound for his 1948 Pisan Cantos.

According to Robert Ellwood in The Politics of Myth, “Three ‘sage’ above all were foundational figured of the twentieth century mythological revival: C.G. Jung, Mircae Eliade and Joseph Campbell.”[27] Although the Bollingen Series was not a Traditionalist organization, it published the works of central figures in Traditionalism, like René Guénon’s leading disciple Ananda Coomaraswamy, and Ur Group member Mircea Eliade, who described Eranos as “one of the most creative cultural experiences of the modern Western world.”[28] In 1947, Ananda Coomaraswamy found Eliade a job as a French-language teacher in the United States, at a school in Arizona Beginning in 1948, he wrote for the journal Critique, edited by Georges Bataille. He also co-edited the Antaios magazine with Ernst Jünger. Eliade collaborated with Carl Jung and the Eranos circle after Henry Corbin recommended him in 1949.

Bollingen Series’s best-selling book, after the I Ching, was Campbell’s best-known work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), in which he discusses his theory based on the Jungian theory of archetypes, of the journey of the hero, his interpretation of the dying-god, shared by world mythologies, termed the monomyth.[29] Campbell gained recognition in Hollywood when George Lucas credited Campbell’s work as influencing his Star Wars saga. However, American folklorist Alan Dundes, who denounced Campbell as a “non-expert,” wrote that “there is no single idea promulgated by amateurs that has done more harm to serious folklore study than the notion of archetype.”[30] According to anthropologist Raymond Scupin, “Joseph Campbell’s theories have not been well received in anthropology because of his overgeneralizations, as well as other problems.”[31] American folklorist Barre Toelken writes, “Campbell could construct a monomyth of the hero only by citing those stories that fit his preconceived mold, and leaving out equally valid stories… which did not fit the pattern.”[32] Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, a former Sanskrit professor at the University of Toronto, said that he once met Campbell, and that the two “hated each other at sight,” commenting that, “When I met Campbell at a public gathering he was quoting Sanskrit verses. He had no clue as to what he was talking about; he had the most superficial knowledge of India but he could use it for his own aggrandizement. I remember thinking: this man is corrupt. I know that he was simply lying about his understanding.”[33] Ellwood says that “Campbell was not really a social scientist, and those in the latter camp could tell” and records a concern about Campbell’s “oversimplification of historical matters and tendency to make myth mean whatever he wanted it to mean.”[34] The critic Camille Paglia, writing in Sexual Personae (1990), described his work as a “fanciful, showy mishmash.”[35]

In 1950, Eliade began attending Eranos conferences, meeting Jung, Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn, Gershom Scholem and the Berkeley anthropologist Paul Radin. An early adviser to the Bollingen Foundation who also had links to Jung, Radin was the son of a rabbi born in Poland in 1883 and raised in New York City. His most well-known publication is The trickster: a study in American Indian mythology (1956), which includes essays by Karl Kerényi, and Jung. Radin, who believed in the importance of Sabbatai Zevi, convinced the Bollingen Foundation and its president, John D. Barrett, to fund a translation Gershom Scholem’s Sabbatai Zevi the Mystical Messiah, which was published with Princeton University Press, under their joint imprint in 1973.[36] Eliade In 1956, Eliade moved to the United States, where he was invited by Joachim Wach to give a series of lectures at the University of Chicago. Wach was descended on both sides from the famous Mendelssohn family, both the crypto-Sabbatean philosopher Moses Mendelssohn and the composer Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Eliade and Wach are generally considered to be the founders of the “Chicago school” that basically defined the study of religions for the second half of the twentieth century.[37]

With Ernst Jünger, Eliade also co-edited the magazine Antaios. Jünger eventually settled in Wilfingen in the house of the Master Forester attached to the ancestral home of his executed friend Graf Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg, who was one of the leading members of the failed plot of 1944 to assassinate Adolf Hitler and remove the Nazi Party from power. There he founded the literary review Antaios with Mircea Eliade.[38] Antaios was a German cultural magazine published from 1959 to 1971 by Ernst Klett, who wanted to involve the scholars of the Eranos circle. It had a conservative orientation and promoted perennial philosophy and the study of archetypes. Julius Evola was published in the magazine twice. In 1946, Jünger met Armin Mohler, who is often considered a central intellectual figure of the post war extreme Right in Germany, and who would become his secretary. Mohler, press secretary for Heidegger and maintained extensive correspondence with Carl Schmitt, was an important scholar on the German Conservative Revolution, and was responsible for popularizing that term, in Die Konservative Revolution in Deutschland 1918-1932: Ein Handbuch, this PhD dissertation published in 1949 under the supervision of Karl Jaspers.[39]

Other people who had been approached but rejected the position of editor of Antaios included Aldous Huxley, Joseph Campbell and Karl Jaspers.[40] As explained by Nevill Drury, Campbell was one of the bridging figures who continued the direct legacy of Carl Jung and who also served as a spiritual mentor to the Human Potential movement.[41] Campbell, like Jung and Mircea Eliade, was also an important figure in the modern promotion of Yoga and Kundalini, an interest they were both preceded in by Carl Jung, whose seminars on Kundalini are compiled in The Psychology of Kundalini Yoga. Campbell regarded Kundalini as “India’s greatest gift to us,” and praised Ramakrishna as “a virtuoso in the experience of the Kundalini transformations.”[42]

Campbell’s role in the construction of Esalen was essential, having held seminars there for twenty years, beginning with his first participation in 1966.[43] Campbell was also a friend of Huston Smith, an Esalen regular and professor of Philosophy and Religion at Syracuse University, who introduced the Dalai Lama to the West. Smith had been a participant in Leary’s Marsh Chapel Experiment under the Harvard Psilocybin Project. Smith developed an interest in the Traditionalism of René Guénon and Coomaraswamy, and was influenced by the writings of Gerald Heard, who arranged for him to meet Aldous Huxley, who introduced him to Vedanta. Huston’s World’s Religions (originally titled The Religions of Man) has sold over two million copies, and remains a popular introduction to comparative religion. Bill Moyers devoted a 5-part PBS special to Smith’s life and work, The Wisdom of Faith with Huston Smith. Smith has produced three series for public television: The Religions of Man, The Search for America, and Science and Human Responsibility.

Enneagram

Shaman of Altai

Carlos Castaneda (1925 – 1998)

As noted by Boekhoven, Esalen became “Crucial for the development of humanistic psychology and the genesis of a field of shamanism...”[44] Three writers in particular are seen as promoting and spreading ideas related to shamanism and neoshamanism: Mircea Eliade, Carlos Castenada, and Michael Harner.[45] When Mircae Eliade’s Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, a historical study of the different forms of shamanism around the world, was published in English in 1964, it was recognized as a seminal and authoritative study on the subject. According to Eliade, a shaman is “…believed to cure, like all doctors, and to perform miracles of the fakir type, like all magicians [...] But beyond this, he is a psychopomp, and he may also be a priest, mystic, and poet.[46] And Eliade argued that the word shaman should not apply to just any magician or medicine man, but specifically to the practitioners of the ancient religion of the Turks and Mongols of Central Asia. The pre-Buddhist Bön culture was the national form of shamanism in Tibet, which was part of Tantric Buddhism, another area of interest to Eliade, who praised Tantra as the highest form of yoga. These claims lined up with those of H.P. Blavatsky, who maintained that Bön shamanism represented the true magical heritage of the Aryan race.[47]

The Esalen Institute served as the primary platform for the leading exponents of neoshamanism, such as Gordon Wasson, Myron Stolaroff, Robert Anton Wilson and his collaborator Terence McKenna. It was Esalen guest Carlos Castaneda who was chiefly responsible for the rise of neoshamanism. Castaneda became famous for having written a series of books that describe his alleged training in shamanism and the use of psychoactive drugs like peyote, under the tutelage of a Yaqui “Man of Knowledge” named Don Juan. Castaneda’s attention was drawn to psychedelics by reading Wasson, Huxley and Andrija Puharich’s Sacred Mushroom: They Key to the Door of Eternity. An offshoot of Gordon Wasson’s soma theories, Puharich discusses how Siberian shamans left their bodies in ecstasy under the influence of fly agaric mushrooms. Castaneda influenced another Esalen teacher, anthropologist Michael Harner, founder of the Foundation for Shamanic Studies, and an early attendee of Anton LaVey’s and Kenneth Anger’s Magic Circle. Harner, derisively referred to as a “plastic shaman,” has been widely accused of inventing his system of American Native spirituality, which he falsely asserted shared “core” elements with those of the Siberian Shamans.[48]

Michael Harner, founder of the Foundation for Shamanic Studies, and an early attendee of Anton LaVey’s and Kenneth Anger’s Magic Circle.

Castaneda was a close friend of a student of Idries Shah, Chilean psychiatrist Claudio Naranjo, who along with Oscar Ichazo, was a key figure in the Human Potential Movement. Ichazo, whose influence at Esalen is legendary, was heavily involved in psychedelic drugs and shamanism. Chilean psychiatrist Naranjo, belonged to the inner circle at Esalen, where he became one of the three successors to Fritz Perls, the founder of Gestalt Therapy. Naranjo is regarded as one of the pioneers of the Human Potential Movement, for integrating psychotherapy and the spiritual traditions through the introduction of Gurdjieff’s “Fourth Way” teachings.[49]

Ichazo founded a human potential movement group known as the Arica School in 1968. Ichazo is considered by many to be the father of the Enneagram of Personality, a model of the human psyche based on Gurdjieff’s enneagram figure which is principally understood and taught as a typology of nine interconnected personality types. Ichazo has applied the enneagram figure in connection with his theory of mechanical ego mechanisms which grow out of psychological traumas suffered at an early age in specific aspects of the human psyche.[50] The popular use of the Enneagram of Personality (as contrasted with the use of enneagrams within the Arica School) began principally with Claudio Naranjo who had studied with Ichazo in Chile.

Naranjo had become disillusioned with Gurdjieff, and turned to Sufism and became a student of Idries Shah, secretary Wicca founder and Crowley successor Gerald Gardner. According to Shah and J.G. Bennett, who was head of British Military Intelligence in Constantinople, Gurdjieff’s “Fourth Way” originated with the Khwajagan, a chain of Naqshbandi Sufi Masters from the tenth to the sixteenth century influenced by Central Asian shamanism. When Idries Shah met J.G. Bennet, he presented him with a document supporting his claim to represent the “Guardians of the Tradition,” which Bennett and others identified with what Gurdjieff had called “The Inner Circle of Humanity.” Idries Shah, in Tales of the Dervishes, later claimed some of his dervish tales originated from “Sarman sufis.” In other books and articles Shah suggested that the Sarman sufis were the esoteric core of the Naqshbandi order.

In 1960, Shah founded Octagon Press, which was named after the octagram, which Shah believed was related to the Enneagram of Gurdjieff. The enneagram is a nine-pointed figure usually inscribed within a circle. Gurdjieff is quoted by Ouspensky as claiming that it was an ancient secret and was now being partly revealed for the first time, though hints of the symbol could be found in esoteric literature. It has been proposed that it may derive from the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, as used in Renaissance Hermeticism, which used an enneagram of three interlocking triangles, also called a nonagram or a nine-pointed figure used by the Christian medieval philosopher Raymond Lull.[51] In The Commanding Self, Shah contends that the Enneagram is of Sufi origin, and that it has also been long known in coded form as an octagram, two superimposed squares with the space in the middle representing the ninth point.

Claudio Naranjo

In June 1962, a couple of years prior to the publication of The Sufis, Shah had also established contact with members of the movement that had formed around the mystical teachings of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. He was eventually introduced to noted student of Gurdjieff, J.G. Bennett, who became convinced that Shah “had a very important mission in the West that we ought to help him to accomplish.”[52] Shah gave Bennett a “Declaration of the People of the Tradition.” Shah declared that the Guardians belonged to an “invisible hierarchy” that had chosen him to transmit “a secret, hidden, special, superior form of knowledge.” It convinced Bennett that Shah was a genuine emissary of Gurdjieff’s “Sarmoung Monastery.”

According to Kripal, like Price, what Naranjo became known for was a creative synthesis of Asian meditation and western psychotherapy. Though his ideas were developed from Tantric Buddhism, he interpreted them in terms of shamanism, and derived from what he called his “tantric journey” which involved a Kundalini experience, which he compared to both being possessed by a serpent and an alchemical process. As Kripal explains:

The “inner serpent” of kundalini yoga is simply a South Asian construction of a universal neurobiology; it is “no other than our more archaic (reptilian) brain-mind.” The serpent power “is ‘us’-i.e., the integrity of our central nervous system when cleansed of karmic interference,” the human body-mind restored to its own native spontaneity.

Put a bit differently, Naranjo’s “one quest” is a religion of no religion that has come to realize how “instinct” is really a kind of “organismic wisdom” and how libido is more deeply understood as a kind of divine Eros that can progressively mutate both spirit and flesh once it is truly freed from the ego.[53]

John C. Lilly studying dolphins

Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary and John C. Lilly

According to John C. Lilly, who had been through the first levels of Ichazo’s Arica training, Ichazo claimed to have “received instructions from a higher entity called Metatron,” and that his group “was guided by an interior master,” the “Green Qutb.”[54] Lilly was also a friend to Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg. When Lilly read Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, he had chosen to give up his study of physics and pursue biology, eventually focusing on neurophysiology. In 1952, Lilly had studied the effects of sensory deprivation tanks, and also briefed the intelligence community with his progress.[55] From experimenting with LSD and ketamine while floating in isolation tanks, Lilly came to believe that he was in psychic contact with the aliens of what he called the Earth Coincidence Control Office, who were guiding events in his life to lead him to work with dolphins, which were psychic conduits between aliens and humans. The 1980 movie Altered States, starting William Hurt, is partly based on his life.

Lilly is known for his work on dolphin-human communication, as well as his experiments using hallucinogens while floating in isolation tanks. While Lilly implies that he left the National Institute of Health because of unethical government interference, his Communications Research Institute (CRI), founded in 1958 to study dolphins in the Virgin Islands, was partially funded by the Air Force, NASA, NIHM, the National Science Foundation, and the Navy.[56] In 1963, Bateson was hired as the associate director of research for Lilly’s CRI, which studied dolphins.[57] Lilly apparently gave dolphins LSD and told a story of one dolphin who seduced a man into having sex with her in a holding tank.[58]

Divine Madness

“Anti-Psychiastrist” R.D. Laing

David Cooper, who coined the term “Anti-Psychiatry”

According to Eliade, divine madness is a part of Shamanism, a state that psychologists would tend to diagnose as mental disease.[59] As indicated by Jeroen W. Boekhoven in Genealogies of Shamanism, it was a shift in modern psychiatry which came to view schizophrenics as seers and artists, which opened the way for the development of neoshamanism. This view was exemplified by Tavistock “anti-psychiatrist” R.D. Laing, for whom mental illness could be a transformative episode whereby the process of undergoing mental distress was compared to a shamanic journey. Thus, Laing opened the way for schizophrenia to be reinterpreted in light of the foundational experiences of the New Age: “Madness need not be all breakdown. It may also be breakthrough.”[60] “Insanity,” said Laing, who was heavily influenced by Nietzsche, “is a sane response to an insane situation.”[61]

Laing and David Cooper were the leading exponents of a new form of cybernetic psychiatry, what came to be known as “anti-psychiatry,” a term coined by Cooper who wrote Psychiatry and Anti-psychiatry in 1971.[62] Anti-psychiatry attacked the psychiatric establishment’s abuse of electro-shock and drug therapies made notorious in Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Laing’s “anti-psychiatry” was influenced by Bateson’s “double bind.” Laing and others argued that schizophrenia resulted from psychological injuries inflicted by invasive “schizophrenogenic” parents or others, and is sometimes seen as a transformative mental state reflecting an attempt to cope with a sick society. To counter the trend, Laing, through the Philadelphia Association founded with Cooper in 1965, set up over 20 therapeutic communities including Kingsley Hall, where mentally ill patients and their doctors lived together in equal status and any medication used was voluntarily.

Other exponents of anti-psychiatry included Thomas Szasz, who introduced the definition of mental illness as a myth in the 1961 book The Myth of Mental Illness. In particular, many anti-psychiatrists came to question the very diagnosis of schizophrenia. As Laing in 1967:

If the human race survives, future men will, I suspect, look back on our enlightened epoch as a veritable age of Darkness. They will presumably be able to savor the irony of the situation with more amusement than we can extract from it. The laugh’s on us. They will see that what we call ‘schizophrenia’ was one of the forms in which, often through quite ordinary people, the light began to break through the cracks in our all-too-closed minds.[63]

Laing, who was himself one of the institute’s teachers, was greatly admired by the founders of the Esalen. Due to his own experience in a mental hospital, Price became interested in the methods of “Anti-Psychiatry” for treating schizophrenia. Murphy and Price were both admirers of R.D. Laing, whom they invited to lead a seminar at Esalen in 1967. In the same year, psychologist Julian Silverman, Esalen’s general manager and researcher on schizophrenia at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at Bethesda, Maryland, came to Esalen to teach a workshop entitled “Shamanism, Psychedelics, and the Schizophrenias.” NIMH was founded by Robert Hanna Felix, 33rd degree Mason, who was a director of the Scottish Rite’s psychiatric research, which operated the Ashbury Medical Clinic in San Francisco that assessed Charles Mason while on parole.[64]

In the summer of 1968, Price recruited Silverman to put together a series of seminars and workshops entitled “The Value of Psychotic Experience.” Participants in the study included Laing, Czech psychiatrist Stanislav Grof, Alan Watts and Fritz Perls.[65] Alan Watts also gave a presentation called “Divine Madness” as part of this series. The following year, Esalen launched the Agnews Project, to study alternative approaches to psychosis in a California State mental hospital, drawing expertise from Esalen faculty with support from NIMH. and the California Department of Health. Silverman headed the program whose objectives were to identify individuals who experienced psychosis and emerge as better integrated personalities, to develop a therapeutic milieu where patients are allowed to experience psychosis unmedicated, and to revise theories and approaches to healing of schizophrenia.[66]

Albert Hoffman, chemist who discovered LSD and Stanislav Grof

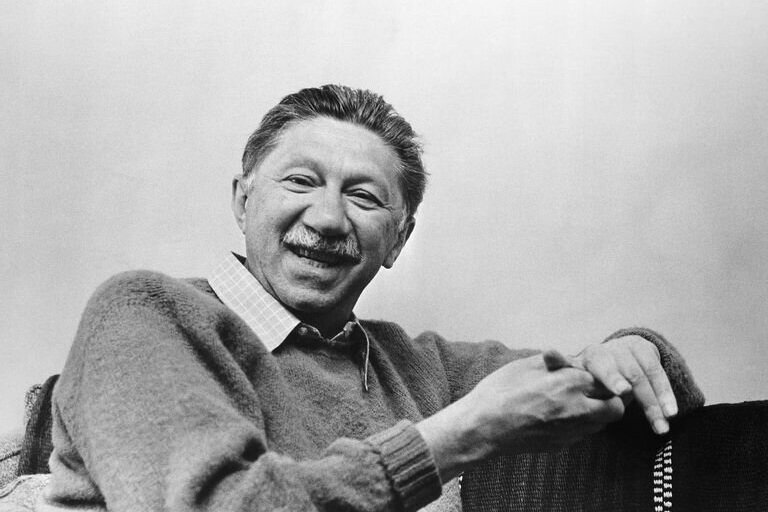

Abraham Maslow who devised “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs”

Stanislav Grof was one of the founders of the field of transpersonal psychology. In 1967, a small working group, including Stanislav Grof, Abraham Maslow, Anthony Sutich, Miles Vich, and Sonya Margulies and Willis Harman’s partner at IFAS, James Fadiman, met in Menlo Park, with the purpose of creating a new psychology that would honor the entire spectrum of human experience. As Grof explained:

The renaissance of interest in Eastern spiritual philosophies, various mystical traditions, meditation, ancient and aboriginal wisdom, as well as the widespread psychedelic experimentation during the stormy 1960s made it absolutely clear that a comprehensive and cross-culturally valid psychology had to include observations from such areas as mystical states; cosmic consciousness; psychedelic experiences; trance phenomena; creativity; and religious, artistic, and scientific inspiration.[67]

During these discussions, Maslow and Sutich accepted Grof’s suggestion and named the new discipline “transpersonal psychology,” a term to replace their own original name “transhumanistic,” or “reaching beyond humanistic concerns.” They soon launched the Association of Transpersonal Psychology (ATP), and later the International Transpersonal Association in 1977, of which Grof was founding president. Grof was also interested in the enhancement of human potential through non-ordinary states of consciousness. He had conducted research with LSD at the Psychiatric Research Center in Prague, followed by similar research at Johns Hopkins University and the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center.

At Esalen, under Price’s encouragement, Grof developed the therapeutic technique of Holotropic Breathwork, which functioned as a substitute for psychedelic drugs. In 1976, Grof and his wife Joan Halifax-Grof led an Esalen seminar for professionals and advanced students on “Schizophrenia and the Visionary Mind,” including guest faculty such as Gregory Bateson, Erik Erikson, Jean Houston, Claudio Naranjo, Kenneth Pelletier, John Perry, Betty Fuller, and Will Schutz, which focused on the biochemical, psychological and cultural variables in schizophrenia, the study of mystical experience, and various techniques for personal self-exploration, including sensory isolation tank, biofeedback, bioenergetic work.[68]

Grof went on to become adjunct faculty member at the California Institute of Integral Studies, a position he holds till today. Integral theory, a philosophy with origins in the work of Sri Aurobindo and Jean Gebser, which seeks a synthesis of the best of pre-modern, modern, and postmodern reality, was developed by Grof’s collaborator Ken Wilber, a major figure in the field of transpersonal psychology.[69] Huston Smith said that Wilber’s integral theory brings Asian and Western psychology together more systematically and comprehensively than other approaches.[70] Wilber argues that the account of existence presented by the Enlightenment is incomplete, as it ignores the spiritual and noetic components of existence. In his work Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (1995), he builds many of his arguments on the emergence of the noosphere and the continued emergence of further evolutionary structures. In a review of the book, Michael Murphy said it was one of the four most important books of the twentieth century, the others being Aurobindo’s The Life Divine, Heidegger’s Being and Time, and Alfred North Whitehead’s Process and Reality.

Neuro-Linguistic Programming

Milton Hyland Erickson (left, 1901 – 1980) American psychiatrist and psychologist close to Gregory Bateson specializing in medical hypnosis and family therapy.

John Grinder

Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), which became popular in the psychoanalytic, occult and New Age movements in the 1980s, and advertising, self-help and politics in the 1990s and 2000s, is a product of the Human Potential Movement (HPM), which started in Esalen. NLP was developed Richard Bandler and John Grinder in the 1970s. Grinder served as a captain in the US Special Forces in Europe during the Cold War, and then went on to work for a US intelligence agency. In the late 1960s, he returned to college to study linguistics and received his Ph.D. degree from the University of California, San Diego in 1971.

The key leaders of the HPM were Fritz Perls, the founder of Gestalt Therapy, who was the first resident scholar in Esalen, and Gregory Bateson. In the early 1950s, Bateson involved Milton Erickson as a consultant as part of his extensive research on communication. The two had met earlier, after Bateson and his wife Margaret Mead had called upon him to analyze the films she had made of trance states in Bali. Through Bateson, Erickson met Bandler and Grinder, amongst others, and had a profound influence on them all.

Richard Bandler

Erickson spoke in 1942 on hypnotism at the Cerebral Inhibition Meeting sponsored by the Macy Foundation. Erickson is noted for his approach to the unconscious mind as creative and solution-generating. Erickson believed that the unconscious mind was always listening and that, whether or not the patient was in trance, suggestions could be made which would have a hypnotic influence, as long as those suggestions found resonance at the unconscious level. In this way, what seemed like a normal conversation might induce a hypnotic trance, or a therapeutic change in the subject. He was noted for his ability to “utilize” anything about a patient to help them change, including their beliefs, favorite words, cultural background, personal history, or even their neurotic habits.[71]

While classical hypnosis depends on techniques for putting patients into suggestive trances (even to the point of losing consciousness on command), NLP is much less intrusive. It is a technique of layering subtle meaning into spoken or written language to implant suggestions into a person’s unconscious mind without them being aware of it. Bandler and Grinder claim there is a connection between neurological processes, language and behavioral patterns learned through experience, and that these can be changed to achieve specific goals in life. Bandler and Grinder also claim that NLP methodology can “model” the skills of exceptional people, allowing anyone to acquire those skills. According to Bandler and Grinder, NLP comprises a methodology termed modeling, plus a set of techniques that they derived from its initial applications.

Of such methods that are considered fundamental, they derived many from the work of Virginia Satir, Milton Erickson and Fritz Perls. In 1964, American social worker and New Age leader Virginia Satir became Esalen’s first Director of Training, which required her to oversee the Human Potential Development Program. Perls became associated with Esalen in 1964, and lived there until 1969. Perls coined the term “Gestalt therapy” to identify the form of psychotherapy that he developed. Bandler and Grinder also drew upon the theories of Bateson, Korzybski and Noam Chomsky and were also influenced by the shamanism described in the books of Carlos Castaneda.[72] They integrated don Juan's use of metaphor and hypnosis and Milton Erickson’s language patterns and metaphor to induce an altered state of consciousness to create deep trance phenomena.

The foreword to Bandler and Grinder’s Trance-formations: Neuro-Linguistic Programming and the Structure of Hypnosis, explains, “What is unique about this book is that it turns the ‘magic’ of hypnosis into specific understandable procedures that can be used not only in doing ‘hypnosis’ but also in everyday communication.”[73] Bandler and Grinder claim that their methodology can codify the structure inherent to the therapeutic “magic” as performed in therapy by Perls, Satir and Erickson, and inherent to any complex human activity, and then from that codification, the structure and its activity can be learned by others. Their 1975 book, The Structure of Magic I: A Book about Language and Therapy, is intended to be a codification of the therapeutic techniques of Perls and Satir. Tony Robbins trained with Grinder and utilized a few ideas from NLP as part of his own self-help and motivational speaking programs.

In 1986, Corine Ann Christensen, a former girlfriend of Bandler’s friend, James Marino, was shot dead in her Santa Cruz townhouse owned by Bandler. Authorities charged Bandler with her murder. Bandler testified that he had been at Christensen’s house and was unable to stop James Marino from shooting Christensen in her face. After five hours and thirty minutes of deliberation, a jury found Bandler not guilty.

[1] ABC Close Up. “Mind Contro: Project MKULTRA (1979). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GwvB08GxIds

[2] “Charles Manson: Music Myth Murder Mysticism Magick Magus Mayhem-A Look Back at the Untold Story of the Manson Family (or, More Manson than You’d Ever Want to Know).” Retrieved from https://carwreckdebangs.wordpress.com/tag/esalen-institute/

[3] Rossman. The Wedding Within the War (Doubleday, 1971), p. 76.

[4] Bill Ellis. Raising the devil: Satanism, New Religions, and the Media (University Press of Kentucky, 2000), p. 178.

[5] As cited in Kurt Andersen. “How America Lost Its Mind.” The Atlantic (September 2017).

[6] Hans Thomas Hakl. Eranos: An Alternative Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century (New York: Routledge, 2014), p. 106.

[7] Wouter J. Hanegraaff. New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought, (Boston, Massachusetts, US: Brill Academic Publishers, 1996), pp. 38–39.

[8] Stevens. Storming Heaven, p. 229.

[9] The Perennial Philosophy, Introduction (London: Chatto & Windus, 1946) p. 1.

[10] Jeffrey J. Kripal. Esalen, America and the Religion of No Religion, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), p. 86.

[11] “The Aquarian Conspiracy”; Konstandinos Kalimtgis David Goldman and Jeffrey Steinberg, Dope Inc.

[12] Barclay James Erickson. “The Only Way Out Is In: The Life Of Richard Price.” In Jeffrey Kripal and Glenn W. Shuck (editors), On The Edge Of The Future: Esalen And The Evolution Of American Culture (Indiana University Press, 2005) p. 139-40.

[13] Kripal. Esalen, p. 86.

[14] Ibid., p. 128.

[15] Ibid.

[16] E. Fuller Torrey. The Mind Game (New York: Emerson Hall Publishers, Inc., 1972), p. 69.

[17] Robert C. Fuller. Americans and the Unconscious (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 36.

[18] Martin and Deidre Bobgan. Hypnosis: Medical, Scientific, or Occultic? (Santa Barbara: EastGate Publishers, 2001) p. 12.

[19] Hakl. Eranos, p. 106.

[20] William Souder. Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck (1st ed.). (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2020). p. 120.

[21] John Straley. “Sitka’s Cannery Row Connection and the Birth of Ecological Thinking.” 2011 Sitka WhaleFest Symposium: stories of our changing seas. (Sitka, Alaska: Sitka WhaleFest, November 13, 2011).

[22] Susan Kaufman. “John Cage, with Merce Cunningham, revolutionised music, too.” Washington Post (August 30, 2012).

[23] Glen Yeadon & John Hawkins. Nazi Hydra in America: Suppressed History of America (Joshua Tree, Calif: Progressive Press, 2008), pp. 43, 80.

[24] See David Livingstone. Ordo ab Chao, Chapter 9: JFK Assassination and Chapter 13: Counterculture.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Hans Thomas Hakl. Eranos: An Alternative Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century (New York: Routledge, 2014), p. 130.

[27] Robert Ellwood. The Politics of Myth (SUNY Press, 1999).

[28] William McGuire. Bollingen: An Adventure in Collecting the Past (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1982), p.151

[29] Hans Thomas Hakl. Eranos: An Alternative Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century (New York: Routledge, 2014), p. 26.

[30] Alan Dundes. “Folkloristics in the Twenty-First Century" in Haring, Lee. ed. Grand Theory in Folkloristics (Indiana University Press, 2016), pp. 16–18, 25.

[31] Raymond Scupin. Religion and Culture: An Anthropological Focus (Prentice Hall, 2000), p. 77.

[32] Barre Toelken. The Dynamics of Folklore (Utah State University Press, 1996), p. 413.

[33] Stephen & Robin Larsen. A Fire in the Mind: The Life of Joseph Campbell (Doubleday, 1991), p. 510.

[34] Robert Ellwood. The Politics of Myth: A Study of C. G. Jung, Mircea Eliade, and Joseph Campbell (Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1999), pp. 131–32, 148, 153.

[35] Camille Paglia. “Pelosi’s Victory for Women.” Salon (November 10, 2009). Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/2009/11/11/pelosi_7/

[36] Yaaco Dweck. “Gershom Scholem and America.” New German Critique, 132, Vol. 44, No. 3 (November 2017).

[37] “Conference on Hermeneutics in History: Mircea Eliade, Joachim Wach, and the Science of Religions, at the University of Chicago Martin Marty Center.” Institute for the Advanced Study of Religion.

[38] James Kirkuk. “Obituary: Ernst Junger.” Independent (February 8, 1998).

[39] Tamir Bar-On. Where Have All The Fascists Gone? (Routledge, 2016); Jacob Taubes. To Carl Schmitt: Letters and Reflections (Columbia University Press, 2013).

[40] Ulrich van Loyen. “Antaios. Zeitschrift für eine freie Welt.” In Matthias Schöning, (ed.). Ernst Jünger Handbuch: Leben – Werk – Wirkung (Stuttgart: Metzler, 2014), p. 223.

[41] Nevill Drury. Stealing Fire from Heaven: The Rise of Modern Western Magic. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[42] Joseph Campbell. “Masks of Oriental Gods: Symbolism of Kundalini Yoga,” Literature of Belief: Sacred Scripture and Religious Experience, ed. Neal E. Lambert (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1981), p. 109–38.

[43] Kripal. Esalen, p. 128; Hakl. Eranos, p. 286.

[44] Jeroen W. Boekhoven. Genealogies of Shamanism: Struggles for Power, Charisma and Authority (Barkhuis, 2011) p. 181.

[45] Juan Scuro & Robin Rodd. “Neo-Shamanism.” Encyclopedia of Latin American Religions (Springer International Publishing, 2015).

[46] Mircea Eliade. Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2004), p. 4.

[47] Isis Unveiled (Theosophical University Press Online Edition, Vol. 2), p. 616.

[48] G. Hobson. “The Rise of the White Shaman as a New Version of Cultural Imperialism.” in Gary Hobson, ed. The Remembered Earth. (Albuquerque, NM: Red Earth Press; 1978) p. 100-108.

[49] “Claudio Naranjo, M.D.,” Blue Dolphin Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.bluedolphinpublishing.com/Naranjo.html

[50] Óscar Ichazo. Interviews with Óscar Ichazo (Arica Press, 1982), p. 14.

[51] James Webb. The Harmonious Circle: The Lives and Work of G.I. Gurdjieff, P.D. Ouspensky, and Their Followers (New York and London: Putnam USA, and Thames and Hudson, 2001).

[52] John G. Bennett. Witness: The autobiography of John G. Bennett. (Tucson: Omen Press, 1974), pp. 355–363.

[53] Kripal. Esalen, p. 177.

[54] John C. Lilly & Joseph E. Hart. “The Arica Training,” Transpersonal psychologies, edited by Charles T Tart (Routledge, 1975).

[55] Marks. The Search for the Manchurian Candidate, pp. 142-4.

[56] David Lipset. Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist (Prentice Hall, 1980), p. 241.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Kripal. Esalen, p. 178.

[59] Harry Eiss. Divine Madness (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), pp. 372–374.

[60] Seth Farber. Madness, Heresy, and the Rumor of Angels: The Revolt Against the Mental Health System (Open Court Publishing, 1993) p. 59.

[61] The British Journal of Psychiatry (2011) 199, 359.

[62] Andrew Pickering. The Cybernetic Brain. p. 7.

[63] R.D. Laing. The Politics of Experience. (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1967) p. 107

[64] Carol Greene. TestTube Murder: The Case of Charles Manson (Germany, 1992).

[65] The Gestalt Legacy Project. The Life and Practice of Richard Price: A Gestalt Biography (Lulu.com, 2014 ) p. 75.

[66] Jane Hartford. “Esalen’s Half-Century ofPioneering Cultural Initiatives1962 to 2012.” Esalen Institute. Retrieved from https://www.esalen.org/sites/default/files/resource_attachments/Esalen-CTR-Pioneering-Cultural-Initiatives.pdf

[67] Stanislav Grof. “A Brief History of Transpersonal Psychology,” StanislavGrof.com.

[68] Jane Hartford. “Esalen’s Half-Century ofPioneering Cultural Initiatives1962 to 2012.”

[69] S. Esbjörn-Hargens. Introduction. Esbjörn-Hargens (ed.) “Integral Theory in Action: Applied, Theoretical, and Constructive Perspectives on the AQAL Model.” (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2010)

[70] Editors of KenWilber.com. “Meta-Genius: A Celebration of Ken’s Writings (Part 1),” KenWilber.com.

[71] Gregg E. Gorton. “Milton Hyland Erickson.” The American Journal of Psychiatry (Washington, 2005). Vol.162, Iss. 7; pg. 1255, 1 pgs.

[72] Terrence L. McClendon. The Wild Days. NLP 1972–1981 (1st ed.) (1989) p. 41.

[73] John Grinder, Richard Bandler & Connirae Andreas, eds., Trance-Formations: Neuro-Linguistic Programming and the Structure of Hypnosis (Moab, UT: Real People Press, 1981) p. 1.

Volume Four

MK-Ultra

Council of Nine

Old Right

Novus Ordo Liberalism

In God We Trust

Fascist International

Red Scare

White Makes Right

JFK Assassination

The Civil Rights Movement

Golden Triangle

Crowleyanity

Counterculture

The summer of Love

The Esalen Institute

Ordo ab Discordia

Make Love, Not War

Chaos Magick

Nixon Years

Vatican II

Priory of Sion

Nouvelle Droite

Operation Gladio