10. The Civil Rights MOvement

Civil Rights Act

After succeeding the assassinated Kennedy, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law on July 2, 1964, finally putting Jim Crow laws to an end, but inciting Southern resentments that had festered since the Civil War, which argued that it was an overreach of federal government. Although Johnson who signed the Civil Rights Act which outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin, according to an internal FBI report from May 1964 released by the Trump administration, an informant told the FBI that the Ku Klux Klan said it “had documented proof that President Johnson was formerly a member of the Klan in Texas during the early days of his political career.”[1] Helping to understand what would emerge to be known as the Southern Strategy, in the 1960s Johnson said in to a young Bill Moyers: “I’ll tell you what’s at the bottom of it. If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.”[2]

Nevertheless, Johnson is a common Jewish name, and both of Lyndon Johnson’s great-grandparents, on the maternal side, were Jewish. Johnson’s maternal ancestors, the Huffmans, apparently migrated to Frederick, Maryland from Germany sometime in the mid-eighteenth century. Later they moved to Bourbon, Kentucky and eventually settled in Texas in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. The grandparents of Lyndon’s mother, Rebecca Baines, were John S. Huffman and Mary Elizabeth Perrin. John Huffman’s mother was Suzanne Ament, a common Jewish name. Perrin is also a common Jewish name.[3] George Washington Baines, the grandfather of Johnson’s mother, was also the president of Baylor University during the American Civil War.

Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Among the guests behind him is Martin Luther King, Jr.

In 2013, the Associated Press reported that newly released tapes from US president Lyndon Johnson’s White House office showed LBJ’s “personal and often emotional connection to Israel.” The news agency also pointed out that during the Johnson presidency, from 1963 to 1969, “the United States became Israel’s chief diplomatic ally and primary arms supplier.”[4] Johnson’s aunt Jessie Johnson Hatcher, a major influence on him, was a member of the Zionist Organization of America. According to historian James M. Smallwood, Congressman Johnson used legal and sometimes illegal methods to smuggle “hundreds of Jews into Texas, using Galveston as the entry port, using false passports and fake visas purchased in Cuba, Mexico and other Latin American countries.[5]

Among Johnson’s closest advisers were several strong pro-Israel advocates, including Benjamin Cohen, who 30 years earlier was the liaison between Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis and Chaim Weizmann, and Abe Fortas, a U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice from 1965 to 1969. Cohen provided crucial advice and counsel to senators working for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the purpose of which was to show the federal government’s support for racial equality following the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown decision.[6] In 1957, Johnson, then Democratic Senate Majority Leader—realizing that the bill could tear apart his party, whose Southern bloc was opposed to civil rights—sought recognition from civil rights advocates for passing the bill, while also receiving recognition from the mostly southern anti-civil rights Democrats for reducing it so much as to kill it.[7] Democratic Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, an ardent segregationist, sustained the longest one-person filibuster in history in an attempt to keep the bill from becoming law.

NAACP

Curiously, the white enemies of Civil Rights Movement were Freemasons, while their counterparts spearheading the movement were also Masons, either from African-American lodges, or at times also from the same Scottish Rite of the Southern Jurisdiction, originally headed by Klansman Albert Pike. In 1956, Southern Baptist pastor and Freemason A.W. Criswell made an address denouncing forced integration to a South Carolina evangelism conference, and a day later to the South Carolina legislature. In it, he was particularly critical of key organizations of the Civil Rights movement like the National Council of Churches and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), calling on fellow Christians to resist these “two-by scantling, good-for-nothing fellows who are trying to upset all of the things that we love as good old Southern people and as good old Southern Baptists,” and referring to the intimidation of “those East Texans… [such] that they dare not pronounce the word chigger any longer. It has to be cheegro.”[8]

Brown vs. Board of Education landmark United States Supreme Court case of 1954 started as a class action suit filed against the Board of Education of the City of Topeka, Kansas in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas. The plaintiffs had been recruited by the leadership of the Topeka NAACP. The NAACP’s chief counsel, Thurgood Marshall—who was later appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967—argued the case before the Supreme Court for the plaintiffs.

The NAACP was founded in 1909 by a larger group including African Americans, along with two whites and one Jew. The Jewish community contributed greatly to the NAACP’s founding and continued financing. In 1914, when Professor Emeritus Joel Spingarn of Columbia University became chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), he recruited for its board such Sabbatean Jewish leaders as Jacob Schiff, Jacob Billikopf, and Rabbi Stephen Wise.[9]

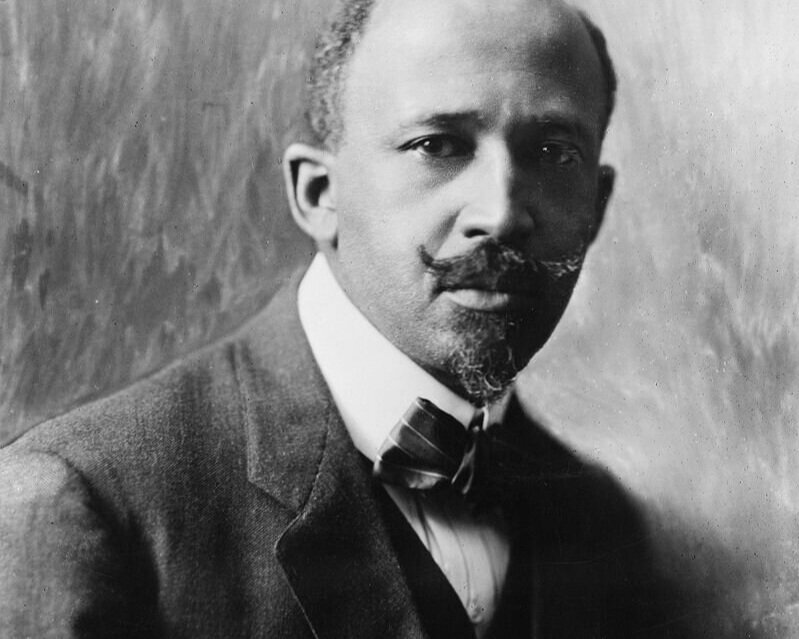

NAACP founder W.E.B. Du Bois (1868 – 1963), member of Sigma Pi Phi, known as “the Boulé.”

At its founding, the NAACP had one African American on its executive board, W.E.B. Du Bois, and it did not elect a black president until 1975. In 1892, Du Bois received a fellowship from the John F. Slater Fund for the Education of Freedmen to attend the University of Berlin for graduate work. Du Bois has angered critics with his remark that it was during his time in imperial Germany that he “began to realize that white people were human.”[10] Du Bois even wrote a poem in German titled Das Neue Vaterland, directed to German immigrants arriving in the United States.

Du Bois studied with some of that Germany’s most prominent social scientists, including Gustav von Schmoller (1838 – 1917), Adolph Wagner (1835 – 1917), and Heinrich von Treitschke (1834 – 1896). Wagner, who was a candidate for the right-wing anti-Semitic Christian Socialist Party, “became a follower of Bismarck’s policy for unifying Germany under Prussian guidance.[11] A famous incident was Wagner’s altercation with Eugen Dühring which resulted in Dühring’s remotion and dismissal from the University of Berlin. Du Bois believed his training by Schmoller would enable him to do “scientific” studies of the plight of the Negroes in the United States.[12] Treitschke was a German historian and National Liberal member of the Reichstag. Treitschke rejected the Enlightenment and liberalism's concern for individual rights and the separation of powers in favor of an authoritarian monarchist and militarist concept of the state. He was an outspoken nationalist, who favored German colonialism and opposed the British Empire. He also opposed Catholics, Poles, Jews and socialists inside Germany. Treitschke was one of the few important public figures who supported anti-Semitic attacks which became prevalent from 1879 onwards. He accused German Jews of refusing to assimilate into German culture and society, and popularized the phrase Die Juden sind unser Unglück! (“The Jews are our misfortune!”), which was adopted as a motto by the Nazi publication Der Stürmer several decades later.[13] Treitschke was held in high regard by the political elites of Prussia and Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow personally declared that he kept a copy of von Treitschke's book for “several years” on his desk.[14]

After completing graduate work at the University of Berlin and Harvard, where he was strongly influenced by his professor William James, Du Bois was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. Early proponents of the eugenics movement did not only include influential white Americans but also several proponent African American intellectuals such as Du Bois, Thomas Wyatt Turner, and many academics at Tuskegee University, Howard University, and Hampton University. Du Bois borrowed eugenic language in his 1903 essay on the “Talented Tenth,” in which he stated “The Negro race, like all other races, is going to be saved by exceptional men.”[15] Du Bois believed “only fit blacks should procreate to eradicate the race's heritage of moral iniquity.”[16] In an article for the June 1932 issue of Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review entitled “A Negro Number,” he argued that birth control for poor African Americans was necessary for the race and that people “must learn that among human races and groups, as among vegetables, quality and not mere quantity really counts.”[17] With the support of leaders like Du Bois, efforts were made to control the reproduction of the country’s black population, like Sanger's 1939 proposal, The Negro Project. Sanger and other members of the new Birth Control Federation of America (BCFA), drafted a report on “Birth Control and the Negro.” In this report, they stated that African Americans were the group with “the greatest economic, health and social problems,” were largely illiterate and “still breed carelessly and disastrously,” a line taken from Du Bois’ article.

Du Bois took a trip around the world in 1936, which included visits to Nazi Germany, China and Japan. While in Germany, Du Bois remarked that he was treated with warmth and respect. After his return to the United States, his positive observations about the Nazi regime were reported in the New York Staatszeitung and Herald, which reported that although he was disturbed by the attitude towards the Jew, “On the other hand the professor observed an unconditional trust in National Socialism and in Hitler and the thankfulness of the order that he has created and for all of the good that he has done during the four years of his time in office.”[18] Apparently, Du Bois was particularly impressed by Rudolf Hess, though he believed that Hess’ influence was declining. The treatment of blacks in Germany, according to Du Bois, expressed, “not a trace at all of racial hatred” and the attitude of the German Press, during the Olympic Games, was completely fair, even friendly towards the black athletes. The situation with the Jews was “very regrettable,” but could not be compared with the situation of the blacks in the United States.

The Boulé

Boulé member Thurgood Marshall (1908 – 1993), first African-American Supreme Court justice.

Du Bois, like Thurgood Marshall and a large number of other members of the NAACP, was belonged to Prince Hall Freemasonry, which was founded by Prince Hall in 1784 and composed predominantly of African Americans. The lodge was started when, prior to the Civil War, Prince Hall and fourteen other free black men petitioned for admittance to the white Boston St. John’s Lodge, but they were declined. Masonic and Grand Lodges generally excluded African Americans. Albert Pike famously wrote in a letter to his brother in 1875, “I am not inclined to mettle in the matter. I took my obligations to white men, not to Negroes. When I have to accept Negroes as brothers or leave Masonry, I shall leave it.”[19] Other NAACP members in Prince Hall included National Chairman Julian Bond, field secretary Medgar Wiley Evers, Executive Director Benjamin L. Hooks, and President and CEO Kweisi Mfume. Other famous Prince Hall Masons included Booker T. Washington, Sugar Ray Robinson, Count Basie, Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Paul Robeson and Lionel Hampton.[20]

Du Bois had also been a member of the Sigma Pi Phi, known as “the Boulé,” which means “a council of noblemen.” The fraternity was founded by Henry McKee Minton, a former graduate of Phillips Exeter Academy, which he modeled on Kappa Epsilon Pi.[21] The most elite high school secret society in America was Kappa Epsilon Pi, founded at Phillips Exeter Academy in 1891 and fashioned as the Preparatory Order of Skull and Bones. The order’s badge was an expensively crafted gold skull and laurel wreath creation, incorporating seed pearls, rubies and emeralds. Exeter’s group became the model for all high school secret societies throughout America.[22]

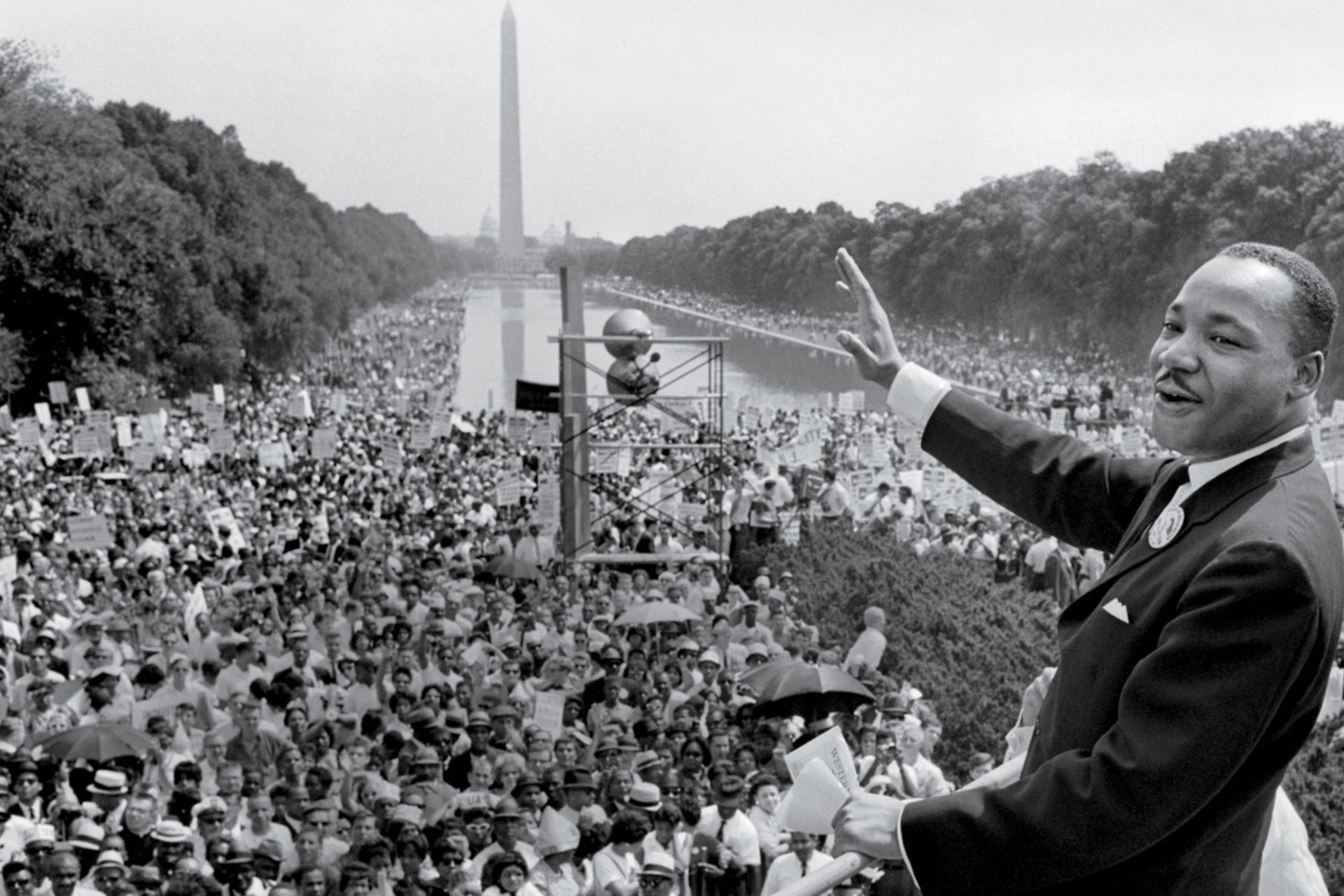

Members of the Boulé included Rev. Martin Luther King, former NAACP President Kweisi Mfume, former UN Ambassador Ralph Bunche, former Atlanta Mayor and UN Ambassador Andrew Young, former Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson, former Virginia Governor L. Douglas Wilder, American Express President Kenneth Chenault, Bobby Scott, C.O. Simpkins, Sr., Ken Blackwell, United States Attorney General Eric Holder, Ron Brown, Vernon Jordan, tennis star Arthur Ashe, Mel Watt, and John Baxter Taylor, Jr., the first African-American to win an Olympic Gold Medal. Sigma Pi Phi is also open to members of all races, as can be demonstrated by its well-known Jewish member Jack Greenberg who succeeded Thurgood Marshall as General Counsel of the NAACP, and became involved in Brown v. Board of Education. Lawrence Otis Graham talks about the organization, and its membership, in his book Our Kind of People: Inside America’s Black Upper Class.

King became a civil rights activist early in his career. He led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in 1957, which played a large role in the Civil Rights Movement. King was the first president of the SCLC, which he led until his death. The SCLC was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. One of the group’s inspirations was the crusades of evangelist Billy Graham, who befriended King after he attended a Graham crusade in New York City in 1957.[23]

Medgar Evers (1925 – 1963), 32º Freemason of the Ancient & Accepted Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction.

Many key figures in the Civil Rights Movement were Masons. Martin Luther King Sr., the father of Martin Luther King Jr., was a member of the 23rd lodge in Atlanta, Georgia. Alex Haley, the writer of Roots and biographer of Malcolm X, was a 33º Mason in the Ancient & Accepted Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction. In other words—the same order as segregationists like Barry Goldstone and Strom Thurmond. Also a 32nd-degree freemason in the same order was Medgar Evers, the NAACP activist who was assassinated by Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens’ Council, in 1963. Musician Bob Dylan wrote his 1963 song “Only a Pawn in Their Game” about the assassination, and Nina Simone wrote and sang “Mississippi Goddam.” The 1996 film Ghosts of Mississippi directed by Rob Reiner, was about the 1994 trial which finally secured a conviction of Beckwith.

In the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the Supreme Court accepted the research of the black sociologist Kenneth Clark that segregation created an inferiority complex in black children. Clark’s study had been commissioned by the American Jewish Committee (AJC), which was founded with the assistance of Jacob Schiff. The Anti-Defamation League and the American Jewish Congress also submitted amicus curiae briefs on behalf of the cause.[24] Also active in the Civil Rights Movement was the AJC’s Rabbi Heschel. He walked arm-in-arm with Dr. Martin Luther King at the march from Selma, and presented King with the Judaism and World Peace Award in 1965. King called Heschel “my rabbi.”[25]

AJC’s Rabbi Heschel walking arm-in-arm with Dr. Martin Luther King at the march from Selma

As reported by Howard Sachar in A History of Jews in America, Jews made up at least 30 percent of the white volunteers who rode freedom buses to the South, registered blacks, and picketed segregated establishments. Among them were several dozen Reform rabbis who marched in Selma and Birmingham. One black leader in Mississippi estimated that, in the 1960s, “as many as 90 percent of the civil rights lawyers in Mississippi were Jewish.”[26]

When two young Jews, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, along with a young black Mississippian, James Cheney were murdered by Klansmen in Meridian, Mississippi, it sparked national outrage and an extensive federal investigation, filed as Mississippi Burning (MIBURN), which later became the title of a 1988 film starring Kevin Costner. All three were associated with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), an African-American civil rights organization that played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is “to bring about equality for all people regardless of race, creed, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, religion or ethnic background.”[27] The organization was influenced by the non-violence resistance tactics of Gandhi. In 1963, the organization helped organize Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous March on Washington.

A key supporter of CORE was Bayard Rustin, a gay man who had been arrested throughout his early career for engaging in public sex with white male prostitutes, as was the case with Augustus Dill, a student of W.E.B. Du Bois and a member of the NAACP.[28] Rustin was a leading activist of the early Civil Rights Movement, and was in the pacifist groups Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the War Resisters League (WRL). A member of the Communist Party before 1941, he collaborated with Prince Hall Mason A. Philip Randolph on the March on Washington Movement in 1941. In 1963, Randolph was the head of King’s March on Washington, which was organized by Rustin. President Reagan issued a statement on Rustin’s death in 1987, praising his work for civil rights and his shift toward neoconservatism.[29] On November 20, 2013, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Nation of Islam

George Lincoln Rockwell (center), Head of the American Nazi Party, at Nation of Islam meeting, Washington, D.C.

Drew’s parents were initiated by Jamal ud Din al Afghani, one of Blavatsky’s “Ascended Masters” and Hajji Sharif who was Saint-Yves d’Alveydre’s source for synarchism.

Anther branch of the Prince Hall Freemasonry is the pseudo-Islamic Nation of Islam, founded by Elijah Muhammad, who was purportedly a manifestation of Paracelsus’ prophecy of Elias Artista.[30] Muhammad had first been a member of the Moorish Science Temple, founded in 1913 by Timothy Drew (1886 – 1929), who gained of thousands of followers who considered a prophet, and knew him as Noble Drew Ali. In an unpublished essay, Ravanna Bey of the Moorish Science Academy of Chicago, reported that the Drew’s parents had encountered Jamal ud Din al-Afghani, Grand Master of Freemasonry in Egypt, and purported member of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, and according to K. Paul Johnson, one of H.P. Blavatsky’s “Ascended Masters,” and Hajji Sharif, Saint-Yves d’Alveydre’s source for synarchism.[31] According to Bey, Afghani was visiting the United States in the winter of 1882-1883 when he initiated the Drews into Salafism and the Brethren of Sincerity or the Ikhwan as-Safa of the eighth century.[32]

One version of Drew’s life, common among members of the Moorish Science Temple, claims that he left home at the age of sixteen and joined a band of gypsies who took him overseas to Egypt.[33] Another version asserts that he ended up in Egypt travelling as a merchant seaman, though some say as a magician in a traveling circus, and ended up in Egypt. There he was initiated by the last priest of an ancient cult of High Magic who took him to the Pyramid of Cheops, and received the name Sharif (Noble) Abdul Ali.[34] In one version of Drew’s biography, the priest saw him as a reincarnation of the founder, while in others, the priest considered him a reincarnation of Jesus, the Buddha, Muhammad and other religious prophets.[35] In Egypt, Drew’s prophecy produced the Circle of Seven Koran. This prophecy might also have taken place in Mecca, where he was empowered by King Abdul Aziz al Said. In 1912 or 1913, he had a cream in which was commanded to found a religion “for the uplifting of fallen mankind.”[36] And especially the “lost-found nation” of American blacks who were actually Moors, after which he founded the he founded the Canaanite Temple in Newark, New Jersey, before relocating to Chicago.

Noble Drew Ali and the Moorish Science Temple of America.

Wallace D. Fard, also known as Wallace Fard Muhammad (c. 1877 – c. 1934)

Drew’s Circle of Seven Koran mentions Marcus Garvey as the “forerunner” of Noble Drew Ali and some say he was Drew Ali’s cousin, just as John the Baptist was Jesus’s cousin.[37] The Circle of Seven Koran was heavily plagiarized from the Rosicrucian text Unto Thee I Grant (1925) and Eve S. And Levi Dowling’s The Acquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ (1909).[38] Dowling said he had transcribed the text of the book from the akashic records, through Visel, “the goddess of Wisdom, or the Holy Breath.” The Gospel claims that Jesus studied with the Brahman and wise men of Buddhism as well as a Persian sage, and that he preached to the Athenians before joining the Egyptian Priesthood of Heliopolis.

Elijah Poole (aka Elijah Mohammed, 1897 – 1975)) and Martin Luther King

Elijah Mohammed was instructed by a mysterious member of the Moorish Science Temple, an Arab named Wallace Fard Muhammed who claimed he was God. Fard, probably born in New Zealand to a man from what would later become Pakistan and an Englishwoman, arrived in Chicago after having entered the United States illegally in 1913, and having joined the Theosophical Society of San Francisco, Marcus Garvey’s UNIA, and in Chicago the Moorish Science Temple.[39] Fard’s religion was a hodge-podge of Islam, Jehovah’s Witness doctrine, Gnosticism, ufology, and heretical Christian teachings and Prince Hall Freemasonry.[40] It basically sets the history of the occult in reverse, where the “Sons of God” or Nephilim, are God, a man, and his council, in “Shambhala,” explicitly associated with the “Great White Brotherhood” of Blavatsky.[41]

According to the FBI, Fard had as many as 27 different aliases and was a sometime petty criminal. Fard’s activities were brought to wider public notice after a major scandal involving an apparent ritual murder in 1932, reportedly committed by one of his early followers, Robert Karriem. Karriem had quoted from Fard’s booklet titled Secret Rituals of the Lost-Found Nation of Islam: “The unbeliever must be stabbed through the heart.”[42] Karriem told the detectives that he intended to carry out more murders, which he called “sacrifices.” He referred to Fard as the “gods of Islam,” and told the investigators, “I had to kill somebody. I could not forsake my gods.”[43] When Fard was interviewed, he told detectives, “I am the Supreme Ruler of the Universe,” resulting in his being placed in a straightjacket and padded cell for psychiatric examination.[44]

According to its former leader Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam received funding from H.L. Hunt.[45] On February 15, 1965, just six days before he was shot at the same location, Malcolm X confessed with regret that he had personally led negotiations with the Ku Klux Klan based on their mutual dedication to segregation. As Malcolm reported, when a number of members from the Nation of Islam were in trouble with the police in Munroe, Louisiana, they got hold of James Venable, the Ku Klux Klan’s lawyer. According to Malcolm, similar arrangements were made with the American Nazi Party of Lincoln Rockwell, who was in regular correspondence with the Nation of Islam’s founder, Elijah Muhammad. John Ali arranged for Rockwell to address the crowd attending the 1962 annual Saviour’s Day Convention at Chicago’s International Amphitheater, where he declared, “Elijah Muhammad is to the so-called Negro what Adolph Hitler was to the German people. He is the most powerful black man in the country. Heil Hitler.”[46] Referring to Hunt’s involvement in the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X remarked, “And never have I seen a man in my life more afraid, more frightened than Elijah Muhammad was when John F. Kennedy was assassinated.”[47] Since then, the Nation of Islam, under its current leader, former Calypso singer Louis Farrakhan, has openly adopted the teachings of the Church of Scientology.

Barry Goldwater

Willam F. Buckley Jr and Barry Goldwater

Following the signing of the Civil Rights Act, 33º degree Scottish Rite Mason Strom Thurmond was one of the first to defect to the Republican Party, leading many other Southern Democrats to vote instead at the national level for the presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater in the same year. Despite losing the 1964 presidential election by a landslide, Barry Goldwater is the politician most often credited with sparking the resurgence of the American conservative political movement in the 1960s, known as the first New Right.[48] As reported by Russ Bellant, in the early 1960’s the ultra-right was planning Goldwater’s presidential campaign effort, in cooperation with the ASC and several far-right groups, including the John Birch Society and the neo-Nazi Liberty Lobby.[49]

In 1963–64, William F. Buckley Jr., a Knight of Malta and Skull and Bonesman, used the National Review as a forum for mobilizing support for Goldwater. According to Alvin Felzenberg, the National Review functioned as Goldwater’s “unofficial headquarters and policy shop.”[50] Buckley’s rise to prominence came at a time of increasing polarization between liberals and conservatives. As conservative activist M. Stanton Evans predicted, “Historians may well record the decade of the 1960s as the era in which conservatism, as a viable political force, finally came into its own.”[51]

Goldwater’s position appealed to white Southern Democrats, and Goldwater was the first Republican presidential candidate since Reconstruction to win the electoral votes of the Deep South states. Though the Goldwater campaign failed to unseat incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson, suffering one of the worst political defeats in American history, it galvanized the formation of a new political movement. In the ensuing years, the increasing conservatism of the Republican Party compared to the liberalism of the Democratic Party led a growing number of conservative white Democrats in the South to vote Republican. Goldwater, who was also a Freemason, was the first ethnically Jewish candidate to be nominated for President by a major American party. Goldwater had come to prominence in the 1950s and 1960s and favored an interventionist foreign policy to battle international communism. He voted against the censure of Senator Joseph McCarthy in 1954.

In 1964, with financial support from the National Review’s chief backer, Roger Milliken, Goldwater fought and won a multi-candidate race for the Republican Party’s presidential nomination. His main rival was New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. At the time of Goldwater’s presidential candidacy, the Republican Party was split between its conservative wing, based in the West and South, and the moderate and liberal wing, based in the Northeast. Sometimes called Rockefeller Republicans, they were members of the Republican Party in the 1930s–1970s who held moderate to liberal views on domestic issues, similar to those of Nelson Rockefeller.

The Goldwater campaign took political ideals that until then had been promoted only by fringe groups like the John Birch Society and brought them into mainstream political discourse. While he disapproved of Welch and his rash utterances, Goldwater was hesitant to denounce the JBS, calling them the “type of people we need in politics” and proclaimed the Birchers were some of the “finest people” in his community.[52]

Freedom School founder Robert LeFevre and Roger Milliken.

Goldwater was not a segregationist, and had fought for integration in Arizona’s National Guard and schools and even joined a local chapter of the NAACP. Goldwater and Milliken both knew that the support of southern conservatives would be essential to the creation of a national conservative movement.[53] Although Goldwater had supported all previous federal civil rights legislation, he decided to oppose the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Many of the states’ rights Democrats were attracted to the 1964 presidential campaign Goldwater, who argued the act was an intrusion of the federal government into the affairs of states and, second, that the act interfered with the rights of private persons to do business, or not, with whomever they chose, even if the choice is based on racial discrimination.

A key factor in this campaign was Buckley’s National Review. As indicated by Joseph E. Lowndes in From the New Deal to the New Right, “One key aim of the magazine which has not been discussed in historical accounts of the modern Right is the attempt to link southern opposition to desegregation to their emerging modern conservative agenda.”[54] That agenda, explains Lowndes, was to link the Civil Rights Movement with government encroachment of New Deal thinking. Within the first month of its publication in 1955, National Review began to build a case that the struggle against civil rights was critical to the conservative movement. National Review’s editors thought that the issue of states’ rights could help avoid a direct discussion of race and thereby help shape other political issues that were important to northern conservatives.

In an editorial written for the National Review titled “Why the South Must Prevail,” Buckley came out firmly in support white supremacy:

The central question that emerges is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in the areas in which it does not predominate numerically. The sobering answer is Yes… because, for the time being, it is the advanced race… The question, as far as the White community is concerned, is whether the claims of civilization supersede those of universal suffrage… The National Review believes that the South’s premises are correct. If the majority wills what is socially atavistic, then to thwart the majority may be, though undemocratic, enlightened.[55]

Milliken moved to South Carolina in 1953 and became an integral part of the rise of the Republican Party in the South. He and Gregory Shorey, the State GOP Chairman, coordinated the nomination of Goldwater as the South Carolina Republican delegation in 1960. It was Milliken, explains Jonathan Katz, “who moved to a solidly Democratic Dixie and transformed it into a bastion of Republicanism.”[56] Milliken built the South Carolina GOP into a national force, convincing Strom Thurmond to switch to the Republican Party.

Roger Milliken, Clarence Manion and another conservative, segregationist, anti-union industrialists, Gregory Shorey, set about preparing Goldwater for President and got Buckley’s brother-in-law Brent Bozell to ghostwrite his 1960 book The Conscience of a Conservative, which emphasized his support for states’ rights and opposition to civil rights and the worldwide spread of communism. Bozell and Buckley had been members of Yale’s debate team. They had co-authored the controversial book, McCarthy and His Enemies, in 1955. Bozell had been Goldwater’s speechwriter in the 1950s, and was familiar with many of his ideals. Goldwater’s book inspired budding conservatives to go on to read Ayn Rand, Milton Friedman, Ludwig von Mises, F.A. Hayek, and many others.[57] In The Conscience of a Conservative, Goldwater wrote:

I have little interest in streamlining government or in making it more efficient, for I mean to reduce its size. I do not undertake to promote welfare, for I propose to extend freedom. My aim is not to pass laws, but to repeal them. It is not to inaugurate new programs, but to cancel old ones that do violence to the Constitution, or that have failed in their purpose, or that impose on the people an unwarranted financial burden. I will not attempt to discover whether legislation is “needed” before I have first determined whether it is constitutionally permissible. And if I should later be attacked for neglecting my constituents “interests,” I shall reply that I was informed their main interest is liberty and that in that cause, I am doing the very best I can.

Manion, who was Dean of the Notre Dame Law School in the 1940s, was a leading conservative who spoke out against communism. Early on Manion, a lifelong Democrat, was a huge supporter of Roosevelt and the New Deal, even writing a book endorsing the agenda in 1939. But when Roosevelt began moving toward interventionist policies, Manion joined the America First Committee and began to rally against interventionism and big government. Manion was also on the executive board of the John Birch Society. In 1957, Manion gave Goldwater a national boost by having him as a guest on his popular radio show. Other guests on the show included General Douglas MacArthur, Jesse Helms, Strom Thurmond, Harry Byrd Sr., Henry Regnery, and Stan Evans, all key players in the rise of the conservative movement. Manion established Victor Publishing Company to print Goldwater’s book.[58]

Milton Friedman

Goldwater alarmed even some of his fellow supporters with his brand of staunch fiscal conservatism and militant anti-communism. He was viewed by many traditional Republicans as being too far-right to appeal to the mainstream majority necessary to win a national election. Nevertheless, Goldwater won the nomination, gaining solid backing from Southern Republicans. Journalist John Adams said, “Rather than shrinking from those critics who accuse him of extremism, Goldwater challenged them head-on” in his acceptance speech at the 1964 Republican Convention, uttering his most famous phrase—a quote from Cicero: “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.”[59]

Through his friendship with Bill Baroody, the president of the American Enterprise Institute and a trusted advisor to Goldwater, Milton Friedman became an economic adviser to the Goldwater campaign.[60] Goldwater selected a cabinet, were he to become president, which included Richard M. Nixon as Secretary of State, Clare Boothe Luce as Secretary of Health, Education, his chief economic adviser Milton Friedman as Secretary of Treasury, Roy Cohn as Attorney General, and William F. Buckley as Secretary of Defense.[61]

Former U.S. Senator Prescott Bush, a moderate Republican from Connecticut, was a friend of Goldwater and supported him in the general election campaign. Bush’s son, George H.W. Bush (then running for the Senate from Texas against Democrat Ralph Yarborough), was also a strong Goldwater supporter in both the nomination and general election campaigns. Conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, later well known for her fight against the Equal Rights Amendment, first became known for writing a pro-Goldwater book, A Choice, Not an Echo, attacking the moderate Republican establishment.

Segregation Forever

Gov. George Wallace holds a press conference outside of University of Alabama to argue against integration of the state's public schools.

George Wallace Documentary - Part 1. (link to Part 2)

Although Johnson had ultimately won the nomination as presidential candidate for the Democratic Party in 1964, Johnson also faced a significant challenge within his own party from the segregationist Governor of Alabama, George Wallace, who did surprisingly well in primaries. Like Goldwater, Wallace was also a Freemason. John Birch Society author Gary Allen, author of None Dare Call it a Conspiracy, was also the speechwriter for Wallace whose anti-desegregation campaign galvanized much of the American far-right and white supremacist groups. George Corley Wallace Jr. was an American politician and the 45th governor of Alabama, having served four nonconsecutive terms between 1963 and 1987. Wallace has the third longest gubernatorial tenure in US history. He was a presidential candidate for four consecutive elections, in which he sought the Democratic Party nomination in 1964, 1972, and 1976, and was the American Independent Party candidate in 1968.

According to Dan T. Carter, a professor of history at Emory University in Atlanta, “George Wallace laid the foundation for the dominance of the Republican Party in American society through the manipulation of racial and social issues in the 1960s and 1970s. He was the master teacher, and Richard Nixon and the Republican leadership that followed were his students.”[62] After four unsuccessful runs for U.S. president, he earned the title “the most influential loser” in twentieth-century American politics. Wallace is remembered for his Southern neo-Dixiecrat and pro-segregation “Jim Crow” positions during the Civil Rights Movement. In his own words: “The President (John F. Kennedy) wants us to surrender this state to Martin Luther King and his group of pro-Communists who have instituted these demonstrations.”[63]

Wallace’s outreach to racists also included an alliance with the white-supremacist and anti-Semitic National States Rights Party (NSRP) was an American nationalist party that found a minor role in the politics of the United States.[64] Despite that, Wallace was a Jewish surname adopted in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as an Americanized form of various Ashkenazic Jewish surnames, such as Wallach.[65] Addressing the Hebrew Association of Greater Miami, Wallace said he had a Jewish uncle and a Jewish first cousin. He said that when he campaigned for the presidency in 1968, “the five Jews in the Alabama Legislature all campaigned for me.”[66] Despite the noted anti-Semitism of his supporters, Wallace avoided saying a negative word about the Jews while campaigning. Dan T. Carter, author of The Politics of Rage, wrote that “some of [Wallace’s] best friends in Montgomery were Jewish,” and, given the waning tolerance of anti-Jewish suspicions in America, “Wallace knew that anti-Semitic statements would devastate his campaign.”[67]

In 1958, Wallace ran in the Democratic primary for governor of Alabama. Wallace’s main opponent was state attorney general John Malcolm Patterson, who ran with the support of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization Wallace had spoken against, winning him the support of the NAACP. However, after he lost the election, Wallace, who had till then adhered to progressive politics and not opposed segregation, decided to exploit racist sentiments to advance his political career.[68] Aide Seymore Trammell recalled Wallace saying, “Seymore, you know why I lost that governor’s race?… I was outniggered by John Patterson. And I’ll tell you here and now, I will never be outniggered again.”[69]

And when he finally ran again for the governorship in 1962, Wallace campaigned on an anti-segregation platform and won in a record landslide. One of Wallace’s supporters, who was horrified by the transformation, asked him to explain himself. Wallace answered, “you know, I tried to talk about good roads and good schools, and all these things that had been part of my career, and nobody listened. And then I began talking about niggers, and they stomped the floor.”[70] According to author Rick Bragg, “The part of the world where I grew up, they’d been waiting for a champion for a long time. And Wallace hit them just as they were at most angry. He hit them at a time when they were looking for somebody to lead them.”[71] Wallace galvanized racist opposition to segregation by standing in front of the entrance of the University of Alabama in an attempt to stop the enrolment of black students, and most notoriously, for deploying the state troopers who brutally beat the nonviolent freedom marchers in Selma on “Bloody Sunday” of March 7, 1965.

The Reconstruction of Asa Carter

The reason for Wallace’s success was the influence of the Klan in Alabama. The key figure in Wallace’s renewed campaign was Asa Earl Carter, a 1950s Ku Klux Klan leader, segregationist speech writer, and later western novelist, who later ran in the Democratic primary for governor of Alabama on a segregationist ticket. It was Carter who co-wrote Wallace’s well-known pro-segregation line from his inauguration speech of 1963, “In the name of the greatest people that have ever trod this earth, I draw the line in the dust, and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” According to Trammell, Carter was a “a man that had connections, good connections with the underworld, you might say. He was our go-between, between the governor and with the Ku Klux Klan. He could keep those people quiet, or he could get them to be very disturbed.”[72]

Carter founded the North Alabama Citizens Council (NACC), an independent offshoot of the White Citizens’ Council movement. Carter was one of the most notorious racists in the state of Alabama, with a long history of violence.[73] A group of his followers had randomly castrated a black man, and attacked singer Nat King Cole on stage. Four of the six involved were convicted of mayhem and sentenced to twenty years, but in 1963 a parole board appointed by Wallace commuted their sentences. In 1958, Carter quit the Klan group he had founded after shooting two members in a dispute over finances. Along with New Jersey white supremacist John Kasper, executive secretary of the Seaboard White Citizens Council, Carter served as agent-provocateur in inciting anti-desegregation demonstrations in Clinton High School in 1956. Kasper became a devotee of Ezra Pound and corresponded with him as a student.[74]

The Clinton Desegregation Crisis was a series of events from 1947 to 1958 that placed the Civil Rights events in Clinton, the seat of Anderson County, on the national stage as one of the flaring points in the modern Civil Rights movement. In 1950, African Americans of Clinton began to challenge issues of black education in federal courts. The local citizens were represented by a powerful group of NAACP attorneys. Z. Alexander Looby and Avon N. Williams of Nashville, who would later gain fame from their role in the Nashville Civil Rights struggle and student movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s. But most important was the role of Thurgood Marshall, whose involvement signaled that the NAACP considered the case of Clinton to be of national significance. The situation came to a head when, in January 1956, Federal Judge Taylor ordered the school board to end segregation by the fall term of 1956.

No public displays of outrage or attempts to stop the process took place in the summer of 1956, and the first few days of integration were friendly. A crisis erupted however, and became national news, when Kasper incited threats, violence, and agitated large crowds. Judge Taylor ordered Kasper’s arrest, an action that was a first in the implementation of the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Asa Carter led protests, until full-scale rioting broke out, which only ended when the National Guard was called in, another first in the Civil Rights movement.

Asa Earl Carter later reinvented himself as Forrest Carter, author of he Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales.

Years later, Carter reinvented himself as a sort of New Age guru, going under the alias of supposedly Cherokee writer Forrest Carter, named after Nathan Bedford Forrest, the founder of the Klan. He wrote The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales, eventually a Clint Eastwood film, and The Education of Little Tree, a best-selling, award-winning book which was marketed as a memoir but which turned out to be fiction. As Joseph E. Lowndes explained, “The Outlaw Josey Wales. Metaphorically linking anti–Vietnam War sentiment, anger over FBI abuse of power, and Indian rights issues to a defense of the white South, the film makes a culturally potent case for backlash against the liberal state.”[75]

Wallace was widely suspected of having dropped out of the presidential race of 1964 to favor Barry Goldwater. Even before his nomination, H.L. Hunt called Wallace from San Francisco and urged him to quit the race. Hunt, who favored Wallace’s ultra-conservative views, had met with him three times that year. James D. Martin, a Gadsden, Ala., oil dealer and Republican leader discussed the problems with Wallace’s candidacy with the Goldwater staff both before and during the Republican convention. Martin also recalled saying, “I have a feeling he [Wallace] is influencing Goldwater’s thinking and that Senator Goldwater is influencing Governor Wallace’s thinking.” [76]

When Wallace announced his withdrawal on CBS’s Face the Nation, on July 19, he said he had “conservatized” both national parties and had thus succeeded in his mission. Most prominent whites who might have been inclined to support Wallace had already joined the Republican party. Those who remained, including Citizens Council officials, switched to Goldwater after his nomination. “It’s not that we’re going along with an individual,” explained Robert M. Shelton of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Imperial Wizard of the United Klans of America, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. “We’re going along with the principles that the Republican party has adopted in its platform.” [77] “It looks like all Americans are going to go with Goldwater,” said Calvin F. Craig of Atlanta, Grand Dragon of the Georgia Realm of the United Klans, who was a State Senate candidate. “Johnson’s hands are so bloody, he can’t hold them out in public any more.”[78] Craig and some other former Wallace supporters argue that his showing in the Wisconsin, Indiana and Maryland Democratic Presidential preferential primaries helped Goldwater win the Republican nomination. It impressed Republicans with the extent of white reaction to the civil rights issue, they contended. “If it hadn’t been for George Wallace, Goldwater would have been a political dead duck today,” Mr. Craig asserted.[79]

Wallace ran again for president in the 1968 election, but as the American Independent Party (AIP) candidate, with financial backing from the son and heir of H.L. Hunt, Nelson Bunker Hunt, who was a member of the Council of the John Birch Society.[80] The AIP was an amalgam of Ku Klux Klan and John Birch Society elements.[81]

Senator No

Senator Jesse Helms (1921 – 2008)

Nixon feared that Wallace might split the conservative vote and allow the Democratic nominee, Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, to win. Nixon ultimately won the election, but Wallace carried five Southern states, won almost ten million popular votes and 46 electoral votes. According to Lowndes, “While later conservatives would distance themselves from Wallace’s overt racism and pugnacious rhetoric, he left an indelible mark on the campaigns of Nixon and later Reagan, both of whom drew from his language of racial, antigovernment populism.”[82] Cognizant of Wallace’s successes, Nixon, with the aid of Harry Dent and Strom Thurmond, who had switched to the Republican Party in 1964, and ran his 1968 campaign on states’ rights and “law and order.” Nixon’s presidency built on the legacy of the Dixiecrats, Goldwater, and Wallace, explains Lowndes, “weaving together racism, conservatism, and populism in a coherent political identity that could claim majoritarian status.”[83] The key was a hypothetical constituency variously called the “silent majority,” the “emerging Republican majority,” “the Forgotten Americans,” and “Middle America.”

Nixon’s substantial landslide victory in the presidential election of 1972, also helped propel the notorious Jesse Helms into office. “Next to Ronald Reagan,” wrote Fred Barnes in the Weekly Standard in 1997, “Jesse Helms is the most important conservative of the last 25 years.” A 33º Mason, Helms was a Grand Orator of the Masonic Grand Lodge of North Carolina.[84] A Southern Baptist, Helms was close to fellow North Carolinian Billy Graham (whom he considered a “personal hero”), as well as Charles Stanley, Pat Robertson, and Jerry Falwell, whose Liberty University erected the Jesse Helms School of Government.[85]

Helms’ campaign manager, Pioneer Fund director, Thomas F. Ellis.

Upon Helms’ retirement from the Senate in 2001, David Broder of The Washington Post criticized Helms as, “the last prominent unabashed white racist politician in this country.”[86] Helms’ home town, Monroe, was notorious as a stronghold of the Ku Klux Klan. Racial oppression was so intense that it sparked one of the most important acts of armed resistance by black residents during the civil rights era, led by Robert F. Williams, head of the Monroe NAACP. In 1950, Helms played a critical role as campaign publicity director for Willis Smith in his US Senate campaign against a prominent liberal, Frank Porter Graham. Smith portrayed Graham, who supported school desegregation, as a “dupe of communists” and a proponent of the “mingling of the races.” Smith’s fliers said, “Wake Up, White People.”[87]

Helms opposed busing, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. Helms called the Civil Rights Act of 1964 “the single most dangerous piece of legislation ever introduced in the Congress,” and sponsored legislation to either extend it to the entire country or scrap it altogether.[88] Helms ran for his first of four terms as a United States Senator in 1972, Congressman Nick Galifianakis. Helms’ campaign was managed by Thomas F. Ellis, a Pioneer Fund director, grantee and close associate of the hate group’s president, Harry Frederick Weyher, Jr., for over 60 years.[89] Helms employed the slogan “Jesse: He’s One of Us,” an implicit innuendo suggesting his opponent’s Greek heritage made him somehow less “American.”

The Almanac of American Politics once wrote that “no American politician is more controversial, beloved in some quarters and hated in others, than Jesse Helms.”[90] Helms’ opposition to social change and what he viewed as legislative overreaching led to his nickname of “Senator No.” He blocked nominations for federal office, withheld funding for the United Nations, opposed gun control and threatened to cancel federal support for arts groups and school busing. He refused to relent on strict U.S. trade embargoes of Cuba, and in 1977, denounced a treaty advanced by Carter to turn over the Panama Canal to Panama. From 1979 to 1986, over the objections of Republican leaders, Helms used parliamentary ploys to scuttle the SALT II arms limitation treaty, which he said represented unwarranted concessions to the Soviet Union.

[1] “JFK files reveal sex parties, a stripper named Kitty, surveillance and assassination plots.” Toronto Sun (October 27, 2017).

[2] Bill D. Moyers. “What the Real President Was Like.” Washington Post (November 13, 1988).

[3] Morris Smith. “Our First Jewish President Lyndon Johnson? – an update!!.” 5 Towns Jewish Times (April 11, 2013).

[4] White. JFK Murder - A Revisionist’s History.

[5] Lenny Ben-David. “A friend in deed.” Jerusalem Post (September 9, 2008).

[6] Robert A. Caro. Master of the Senate (New York: Alfred a Knopf Inc. 2002). Chapter 39.

[7] Ibid., pp. 949-51, 1008.

[8] Curtis Freeman. “‘Never Had I Been So Blind’: W. A. Criswell’s ‘Change’ on Racial Segregation.” Journal of Southern Religion. 2007, 10: 1–12.

[9] Howard Sachar. “Working to Extend America’s Freedoms: Jewish involvement in the Civil Rights movement.” Excerpt from A History of Jews in America, (Vintage Books). MyJewishLearning.com.

[10] Kenneth Barkin. “W. E. B. Du Bois' Love Affair with Imperial Germany.” German Studies Review, Vol. 28, No. 2 (May, 2005), p. 286.

[11] Adolph Wagner. Briefe – Dokumente – Augenzeugenberichte, 1851–1917. Heinrich Rubner, ed. (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1978), p. 435.

[12] Kenneth Barkin. “W. E. B. Du Bois' Love Affair with Imperial Germany.” German Studies Review, Vol. 28, No. 2 (May, 2005), p. 289.

[13] Alfred Andrea and James Overfield, eds. The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Volume II: Since 1500. (Cengage Learning, 2011). pp. 294–95.

[14] Michael Burleigh. Ethics and extermination: reflections on Nazi genocide (Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 17

[15] W.E.B Du Bois, “Talented Tenth” in The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative American Negroes of To-Day (New York: James Potts and Company, 1903), p. 75.

[16] Gregory Dorr & Angela Logan. "Quality, not mere quantity counts: black eugenics and the NAACP baby contests.” In Paul Lombardo (ed.). A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era (Indiana University Press, 2011), pp. 68–92.

[17] W.E.B Du Bois, “Black Folks and Birth Control,” Birth Control Review (June 1932), p. 166.

[18] “Man of Color tours Nazi-Germany.” New York Staatszeitung and Herald (January 29, 1937).

[19] William H. Upton. Negro Masonry (New York: AMS Press, 1975).

[20] Bro. Timothy A. Johnson. “Famous Prince Hall freemasons.” Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon (Accessed October 10, 2002).

[21] Tamara L. Brown, Gregory Parks & Clarenda M. Phillips. African American Fraternities and Sororities: The Legacy and the Vision (University Press of Kentucky, 2005) p. 98.

[22] Edward Echols. “The Phillips Exeter Academy, A Pictorial History.” (Exeter Press, 1970).

[23] Steven P. Miller. Billy Graham and the Rise of the Republican South (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009), p. 92.

[24] “Judge Joseph M. Proskauer Dies at 94.” Jewish Telegraph Agency (September 13, 1971).

[25] Peter Dreier. “Selma ‘s Missing Rabbi.” Huffington Post (January 17, 2015).

[26] Howard Sachar. A History of Jews in America (Vintage Books, 1993).

[27] “About Congress of Racial Equality | (702) 633-4464.” Congress Of Racial Equality.

[28] Vincent Woodard & Dwight McBride. The Delectable Negro: Human Consumption and Homoeroticism within US Slave Culture (New York University Press, 2014), p. 21.

[29] Justin Vaïsse. Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement (Harvard University Press, 2010), pp. 71-75.

[30] Wesley Muhammad. “The Wise of this World Awaited Elijah.” The Final Call (December 10, 2012).

[31] K. Paul Johnson. The Masters Revealed, p. 47.

[32] Peter Lamborn Wilson. Sacred Drift: Essays on the Margins of Islam (City Lights Books, 1993), p. 16.

[33] Paghdiwala, Tasneem. “The Aging of the Moors.” Chicago Reader (November 15, 2007).

[34] Peter Lamborn Wilson. Sacred Drift: Essays on the Margins of Islam (City Lights Books, 1993), p. 16.

[35] Paghdiwala, Tasneem. “The Aging of the Moors.” Chicago Reader (November 15, 2007).

[36] Peter Lamborn Wilson. Sacred Drift: Essays on the Margins of Islam (City Lights Books, 1993), p. 16.

[37] Peter Lamborn Wilson. Sacred Drift: Essays on the Margins of Islam (City Lights Books, 1993), p. 16.

[38] Anouar Majid. We are All Moors: Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities (University of Minnesota Press, 2009), p. 80.

[39] Anouar Majid. We are All Moors: Ending Centuries of Crusades Against Muslims and Other Minorities (University of Minnesota Press, 2009), p. 80.

[40] C. Eric Lincoln. The Black Muslims in America. 1st ed., (Beacon Press, Boston, 1961), p.108; and Malcolm X, p. 12.

[41] True Islam. The Book of God: An Encyclopedia of Proof that the Original Man is God (Atlanta: All in All Publishing, 1999).

[42] “Head of Cult Admits Killing,” Detroit Free Press, (November 21, 1932), p. 1; Sergeant Sam Smith, “Master Fard’s Deceptions and Doctrines.”

[43] Michael Newton, Holy Homicide: An Encyclopedia of Those Who Go With Their God…And Kill! (Loompanics Unlimited, Port Townsend, Washington, 1998), p. 185.

[44] “New Human Sacrifice with a Boy as Victim is Averted by Inquiry,” Detroit Free Press, (November 26, 1932), p. 1.

[45] Karl Evanzz. The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X (New Wave Books, 2011).

[46] Karl Evanzz. The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X (New Wave Books, 2011).

[47] David Miller. The JFK Conspiracy (Writers Club Press, 2002). P. 194.

[48] Robert Poole. “In memoriam: Barry Goldwater.” Reason (Obituary), (August–September 1998).

[49] Bellant. The Coors Connection, p. 38.

[50] George Will. “Buckley captained conservatism before it was hijacked.” Washington Post (June 1, 2017).

[51] M. Stanton Evans. Revolt on the campus (Chicago, January 1, 1961)

[52] Alvin Felzenberg. “The Inside Story of William F. Buckley Jr.’s Crusade against the John Birch Society.” The Atlantic (June 20, 2017).

[53] Jonathan Katz. “The Man Who Launched the GOP's Civil War.” Politico (October 1, 2015).

[54] Lowndes. From the New Deal to the New Right, p. 49.

[55] William F. Buckley, Jr. “Why the South Must Prevail.” National Review (August 24, 1957).

[56] Jonathan Katz. “The Man Who Launched the GOP's Civil War.” Politico (October 1, 2015).

[57] Robert Poole. “In memoriam: Barry Goldwater." Reason (Obituary), (August–September 1998).

[58] Fred Lucas. The Right Frequency: The Story of the Talk Giants Who Shook Up the Political and Media Establishment (History Publishing Company, 2012).

[59] Robert Andrews, ed. Famous Lines: A Columbia Dictionary of Familiar Quotations (1997). p. 159.

[60] Brian Doherty. Radicals for Capitalism, p. 308.

[61] “Goldwater Cabinet Is Said to Include Mrs. Luce and Nixon.” New York Times (November 1, 1964); Mechaman. “The Cabinet of Barry Goldwater.” US Election Atlas (October 09, 2010).

[62] Dan Carter, quoted in John Anderson. “Former governor shaped politics of Alabama, nation.” The Huntsville Times (September 14, 1998), p. A1, A8.

[63] Alabama Governor George Wallace, public statement of May 8, 1963 in The New York Times (May 9, 1963).

[64] Carter. The Politics of Rage.

[65] “Wallace Family History.” Ancestry.ca (accessed January 28, 2018).

[66] “George Wallace is Jewish–almost.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency (February 10, 1972).

[67] Chad Weisman. “In US elections, a history of anti-Semitism.” The Times of Israel (August 30, 2016).

[68] George Wallace: Settin’ the Woods on Fire (Directors: Daniel McCabe, Paul Stekler, 2000).

[69] Dan T. Carter. From George Wallace to Newt Gingrich: Race in the Conservative Counterrevolution, 1963–1994 (Louisiana State University Press, 1996), p. 2.

[70] Ibid.

[71] Daniel McCabe, Paul Jeffrey Stekler & Steve Fayer. “Wallace: Settin’ the Woods on Fire.” Big House Production (2000).

[72] George Wallace: Settin’ the Woods on Fire. Directors: Daniel McCabe, Paul Stekler.

[73] The Reconstruction of Asa Carter (PBS, 2010).

[74] “Jail Term Upheld for Bias Leader: Kasper, Foe of Integration, Loses Appeal in Tennessee School Disorders Case Details of the Ruling Faces Another Trial.” New York Times (June 2, 1957). p. 57.

[75] Lowndes. From the New Deal to the New Right, p. 9.

[76] Claude Sitton. “Wallace Called Reluctant in Dropping Campaign.” New York Times (July 30, 1964).

[77] Ibid.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Darren E. Grem. The Blessings of Business: How Corporations Shaped Conservative Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2016).

[81] Russ Belmont & Louis Wolf. “The Free Congress Foundation Goes East.” Covert Action Bulletin, Number 35 (Fall 1990), p. 29.

[82] Lowndes. From the New Deal to the New Right.

[83] Ibid.

[84] “Jesse Helms.” The Daily Telegraph (July 6, 2008).

[85] Marjorie Hunter. “Not So Vital Statistics on Mr. Helms.” The New York Times (January 6, 1982). p. 16.

[86] David S. Broder. “Jesse Helms, White Racist.” Washington Post (July 7, 2008).

[87] Thomas Borstelmann. The Cold War and the Color Line: American Race Relations in the Global Arena (Harvard University Press, 2003). pp. 65–66.

[88] Nicholas Ashford (August 6, 1981). “Reagan backs extension to black voting Act”. The Times. p. 4.

[89] “From eugenics to voter ID laws: Thomas Farr’s connections to the Pioneer Fund.” Southern Poverty Law Center (December 4, 2017).

[90] “Senator No: Jesse Helms” UNC TV. Retrieved from http://www.unctv.org/senatorno/film/index.html

Volume Four

MK-Ultra

Council of Nine

Old Right

Novus Ordo Liberalism

In God We Trust

Fascist International

Red Scare

White Makes Right

JFK Assassination

The Civil Rights Movement

Golden Triangle

Crowleyanity

Counterculture

The summer of Love

The Esalen Institute

Ordo ab Discordia

Make Love, Not War

Chaos Magick

Nixon Years

Vatican II

Priory of Sion

Nouvelle Droite

Operation Gladio