13. Counterculture

Beat Generation

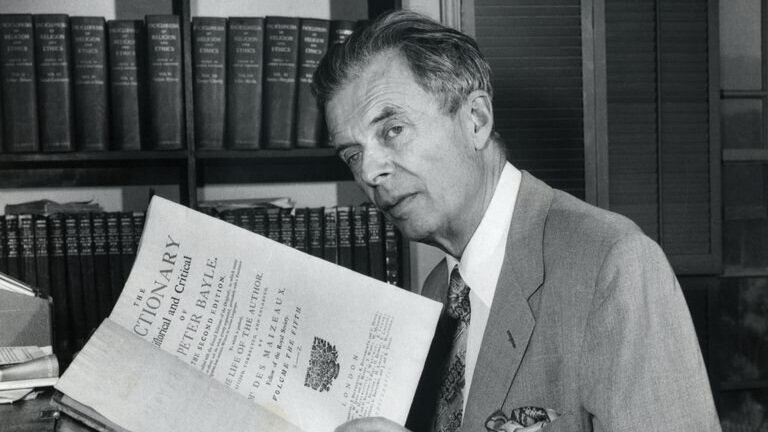

The Cybernetics Group led the foundation for the counter-culture of the 1960s through the promotion of the use “mind-expanding” possibilities of “psychedelic” drugs, which—along with the antinomianism of the occult, rooted, ultimately, in Sabbateanism—were combined with left-wing causes to produce the New Left. As outlined by Aldous Huxley, the great fiend of the twentieth century, writing in Esquire in 1949, “We have had religious revolutions, we have had political, industrial, economic and nationalistic revolutions. All of them, as our descendants will discover, were but ripples in an ocean of conservatism – trivial by comparison with the psychological revolution toward which we are so rapidly moving. That will really be a revolution. When it is over, the human race will give no further trouble.”[1] Huxley clarified his vision in a speech to Tavistock Group at the University of California Medical School in 1961:

There will be, in the next generation or so, a pharmacological method of making people love their servitude, and producing dictatorship without tears, so to speak, producing a kind of painless concentration camp for entire societies, so that people will in fact have their liberties taken away from them, but will rather enjoy it, because they will be distracted from any desire to rebel by propaganda or brainwashing, or brainwashing enhanced by pharmacological methods. And this seems to be the final revolution.[2]

Aldous Huxley

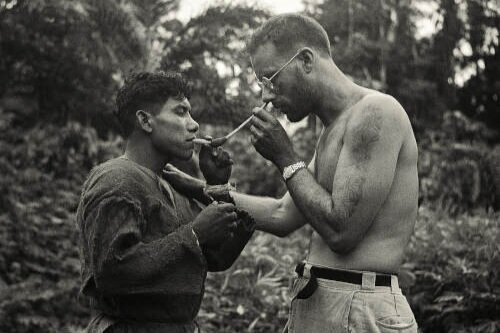

Gregory Bateson, original member of the Cybernetics Group, and who recommended the founding of the CIA.

The Macy Foundation’s chief LSD executive Harold Abramson gave LSD for the first time to Gregory Bateson. Bateson then became the director of a hallucinogenic drug experimental clinic at the Palo Alto Veterans Administration Hospital on behalf of the CIA.[3] It was in 1956, while at the Palo Alto Veterans Hospital, that Bateson developed his theory of “double bind” in the context of schizophrenia. Effectively, Bateson connection schizophrenia to trauma, by describing the double-bind as an ultimatum imposed on the “victim,” that required him or her to perform some unwanted action, under threat of an equally unwanted consequence. According to Bateson, this may have either of two forms: “Do not do so and so, or I will punish you,” or “If you do not do so and so, I will punish you.” The double bind, explains Bateson, may be inflicted by the mother alone or by some combinations of mother, father, and/or siblings. The double bind may even be inflicted through hallucinatory voices.[4]

Allen Ginsberg

Bateson introduced LSD to Beat poet Allen Ginsberg (1926 – 1997). In the 1960s, the hippie and larger counterculture movements that resulted from the diffusion of psychedelics incorporated elements of the earlier Beat movement. Allen Ginsberg referred to their activities as “being part of a cosmic conspiracy… to resurrect a lost art or a lost knowledge or a lost consciousness.”[5] The Beat Generation poets inherited their ideas from the avant-garde, and Ginsberg and Gregory Corso were greatly influenced by Surrealism. Ginsberg cites a number of influences in his work, including that of Apollinaire and Andre Breton. In Paris, Ginsberg and Corso met their heroes, the pioneers of Dada and Surrealism, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Benjamin Péret, and to show their admiration Ginsberg kissed Duchamp’s feet and Corso cut off Duchamp’s tie.[6]

The leading figure of the Beat Generation and a major postmodernist author, considered to be “one of the most politically trenchant, culturally influential, and innovative artists of the twentieth century,” was Ginsberg’s lover, William S. Burroughs.[7] Burroughs attended Harvard, and later attended medical school in Vienna. After being turned down by the OSS and US Navy in 1942 to serve in World War II, he dropped out. He then became afflicted with the drug addiction that affected him for the rest of his life, while working a variety of jobs. In 1943, while living in New York, he befriended Ginsberg and Kerouac.

Lionel Trilling

Ginsberg studied at Columbia University where he befriended Kerouac, the author of On The Road, which is considered a defining work of the postwar Beat and Counterculture generations. At Columbia, Ginsberg and Kerouac studied under Lionel Trilling, who was one of the “non-communist left” agents implicated by Frances Stonor Saunders as part of the CIA’s “Cultural Cold War.” Trilling had joined the Partisan Review, which first served as the voice of the American Communist Party, but which later became staunchly anti-Communist after Stalin became leader of the Soviet Union. Burroughs and Kerouac got into trouble with the law for failing to report a murder involving Lucien Carr, also a student of Trilling. Carr had killed David Kammerer, a childhood friend of William S. Burroughs, in a confrontation over Kammerer’s incessant and unwanted advances.

Kerouac also suffered from mental illness. He joined the United States Merchant Marine in 1942, and then the Navy in 1943, but he served only eight days of active duty before being put on the sick list. According to his medical report, Kerouac said he “asked for an aspirin for his headaches and they diagnosed me dementia praecox and sent me here.” The medical examiner reported Kerouac’s military adjustment was poor, quoting Kerouac: “I just can’t stand it; I like to be by myself.” Two days later he was honorably discharged with a diagnosis of “schizoid personality.”[8]

Ginsberg’s own mother Naomi was institutionalized for schizophrenia in the notorious Rockland State Hospital. Naomi was a Communist while Allen’s father Louis was a socialist. At times Naomi thought President Roosevelt had placed wires in her head and sticks in her back. Naomi regularly paraded around the house in the nude, and as biographer Bill Morgan wrote of what eventually transpired, “It certainly appears that if Naomi didn’t make sexual advances to her son, she came pretty close to it.”[9] His experiences with his mother and her mental illness were a major inspiration for his two important works, “Howl” and his long autobiographical poem “Kaddish for Naomi Ginsberg.”

New York State Psychiatric Institute, run by Dr. Nolan D. C. Lewis, the Scottish Rite’s Field Representative of Research on Dementia Praecox (schizophrenia)

Ginsberg himself would be diagnosed with the same condition. In June 1949, Ginsberg was arrested as an accessory to crimes carried out by his friends, who had stored stolen goods in Ginsberg’s apartment. As an alternative to a jail sentence, Trilling arranged with the Columbia dean for a plea of psychological disability, on condition that Ginsberg was admitted to the New York Psychiatric Institute.[10] The director of research at the institute was former Jewish-Nazi doctor Franz J. Kallmann, a student of Dr. Ernst Rüdin, one of the architects of racial hygiene policies in Nazi Germany. The institute was run by Dr. Nolan D.C. Lewis, the Scottish Rite’s Field Representative of Research on Dementia Praecox. The institute had been involved in running secret experiments in the use of mescaline with the U.S. Army.[11] Dr. Lewis, as Director of Psychiatric Institute, surrounded himself with scientists such as Paul Hoch, later commissioner, New York State, and one of the original two pioneers to investigate and publish investigations of LSD and mescaline. Later Lewis organized the New Jersey Neuropsychiatric Institute in Princeton, and in 1961 Dr. Humphry Osmond joined him as the third full time Director.[12]

Ginsberg was committed to the New York State Psychiatric Institute because a year earlier, in an apartment in Harlem, after masturbating, he had an auditory hallucination while reading the poetry of William Blake (later referred to as his “Blake vision”). At first, Ginsberg claimed to have heard the voice of God, but later interpreted the voice as that of Blake himself reading Ah, Sunflower, The Sick Rose, and Little Girl Lost, also described by Ginsberg as “voice of the ancient of days.” The experience lasted several days. Ginsberg believed that he had witnessed the interconnectedness of the universe. He explained that this hallucination was not inspired by drug use, but said he sought to recapture that feeling later with various drugs.[13]

Howl, the epic poem for which he is best known, was dedicated to Carl Solomon, whom he had met in the Psychiatric Institute. Solomon joined the United States Maritime Service in 1944, and during his travels became exposed to Surrealism and Dada, ideas that would inspire him throughout his life. It was shortly after this period that Solomon was voluntarily institutionalized, a gesture he made as a Dadaist symbol of defeat. “Who are you?” Solomon asked Ginsberg at their first meeting. Ginsberg replied “I’m Prince Myshkin,” the holy fool of Dostoevsky’s novel The Idiot. “Who are you?” Ginsberg asked. “I’m Kirillov,” said Solomon, referring the nihilistic character in The Idiot who declares “I will assert my will,” and then kills himself.[14] One of Solomon’s best-known pieces of writing is Report from the Asylum: Afterthoughts of a Shock Patient.

William S. Burroughs

Burroughs was known to have a morbid obsession for weapons which he kept around himself at all times. Even in his later years, he still retained a large collection of handguns, rifles and shotguns, slept with a .38 under his pillow, and never went out unless armed, and not only with a pistol but also with mace, a blade disguised as a credit card and a steel whip. He often seemed far too well informed about the efficiency of his weapons in inflicting particular types of injuries, fatal or otherwise. He was known to sport a cane with a sword concealed inside it, and another cane that fired cartridges.[15]

It is possible that Burroughs’ rejection from the OSS merely served as a cover to allow him to infiltrate the underground more effectively. Always dressed in a suit, tie, trench coat and fedora, Burroughs looked more like E. Howard Hunt than the radical bohemians he inspired. Much of Burroughs’ work, which is semi-autobiographical, covers a level of activity and travel which would suggest intelligence work. It primarily draws from his experiences as a heroin addict, as he lived throughout Mexico City, London, Paris, Berlin, the South American Amazon and Tangier in Morocco. His Naked Lunch, which details the adventures of William Lee, aka “Lee the Agent,” who is Burroughs’ alter ego in the novel, may have been an admission to his secret work as an assassin for the CIA, and of his penchant for sadism. Burroughs also eerily referred to himself as an “exterminator,” referring to one of the many odd jobs he had taken.

Scene in Tangiers from Naked Lunch by artist Rich Kelly

William S. Burroughs’ lifelong friend, Skull and Bones member William F. Buckley Jr, who worked for the CIA in Mexico during the period 1951–1952.

To escape possible detention in Louisiana or forging a narcotics prescription, Burroughs fled to Mexico where he attended classes at the Mexico City College in 1950 studying with R.H. Barlow, a personal friend of H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard. In that same year, E. Howard Hunt became station chief in Mexico City, where he supervised his lifelong friend William F. Buckley Jr, who worked for the CIA in Mexico during the period 1951–1952. In Mexico, Hunt helped devise Operation PBSUCCESS, the successful covert plan to overthrow Jacobo Arbenz, the elected president of Guatemala.

It was in Mexico that Burroughs was also guilty of having “accidently” shot his wife in a drunken game of “William Tell.” After the incident he lamented: “I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from Control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.” [16] As late as 1992, Burroughs attempted to have the “Ugly Spirit” exorcised by a Navajo shaman. Burroughs had warned the shaman of the challenge before him, in that he “had to face the whole of American capitalism, Rockefeller, the CIA… all of those, particularly Hearst.” [17] Afterward he told Ginsberg, “It’s very much related to the American Tycoon. To William Randolph Hearst, Vanderbilt, Rockefeller, that whole stratum of American acquisitive evil. Monopolistic, acquisitive evil. Ugly evil. The ugly American. The ugly American at his ugly worst. That’s exactly what it is.”[18]

Harvard Professor Richard Evans Schultes being administered a dose of Amazonian tobacco.

After leaving Mexico, Burroughs had drifted through South America for several months with Ginsberg to experiment with ayahuasca, whose active ingredient is DMT, having read that it increases telepathic powers. There he met with Wasson collaborator and Harvard ethnobotanist, Richard Evans Schultes. Schultes, in both his life and his work, has directly influenced a number of notable figures, including Allen Ginsberg and Timothy Leary. Schultes’ book The Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers, co-authored with LSD chemist Albert Hofmann is considered his greatest popular work.

Burroughs exercised a life-long fascination with the occult. As a child, Burroughs experienced visions, and in his own words, he said, “I’ve always been a believer in spirits, the supernatural, like my mother. It was a weird family.”[19] Burroughs delved into witchcraft, to understand these visions, and Tibetan Tantra and read numerous books on the subject, including Sir John Woodroffe’s translation of the Mahanirvana Tantra. He studied astrology and took up yoga, sometimes locking himself in his room for several days, when friends heard him mumbling to himself in subvocal speech as part of his yoga training. [20] Burroughs was also interested in the Orgone theories of Wilhelm Reich. Burroughs’ interest in Sufism may be attributable to his fondness of repeating the phrase attributed to Hassan ibn Sabba, the leader of the eleventh century Ismaili terrorist society, known as the Assassins, who said: “nothing is true and all is forbidden.”

Brion Gysin and Albert Hoffman, Swiss chemist who discovered LSD.

Burroughs went to Tangiers in 1954, and was introduced to the secrets of Moroccan magic by Brion Gysin, who was an expert in the subject. Describing Burroughs’ weird aura, Gysin explained, “An odd blue light often flashed around under the brim of his hat.”[21] Burroughs was called El Hombre Invisible (“the Invisible Man”) by the Spanish boys in Tangiers. Burroughs befriended Paul Bowles, who had been a part of Gertrude Stein’s literary and artistic circle and a friend of Stephen Spender and Christopher Isherwood, and who introduced him to Ahmed Yacoubi (1928–1985) a Moroccan painter and story-teller. Burroughs liked Yacoubi because he was very much into magic, and Yacoubi thought Burroughs was a great magic man. Although Burroughs did not get along well with Bowles’s wife Jane, he “had no difficulties” with her Moroccan girlfriend Sherifa: “She thought I was a sorcerer, I was a magic man, a holy man.”[22]

Burroughs said of Gysin, “He was, is, a tremendous influence, he introduced me to the whole magical universe… we had extraordinary, hallucinatory encounters.”[23] From Tangier, Burroughs and Gysin went to the “Beat Hotel” in Paris in 1959, where they conducted scrying and mirror-gazing sessions among other occult experiments. Unfazed by the paranormal activity they were able to produce, Burroughs described, “It was a great period, a lot of fun, just a lot of fun. The thing about it for me, about magic, and that whole area of the occult, is that it is FUN! Fun, things happen. It’s great. And none of it ever bothers me, you can’t get too extreme.” [24] This was despite the fact that, on one occasion, a friend peeked in, and happened to see a spirit materialize. Burroughs said, “He took one look and said, ‘Oh shit!’ and walked out.” [25]

Rue Git-le-Coeur, Paris, site of the “Beat Hotel”

According to Felix J. Fuchs, “The study of communication and control in systems defined by feedback loops with their ample stock of social implications, as described in the works of Norbert Wiener, had a profound impact on writers such as John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Thomas Pynchon, William S. Burroughs or Kurt Vonnegut.”[26] As John Geiger discovered, if you look at the works of Aldous Huxley or Timothy Leary or William Burroughs and the Beats, you find cybernetics pioneer Grey Walter.[27] An American-born British neurophysiologist and robotician, Walter was an invited guest at the tenth and last of the U.S. Macy cybernetics conferences in 1953. A quick glance at Naked Lunch (1959) reveals that Burroughs was an attentive reader of Walter’s The Living Brain, but, explains Andrew Pickering in The Cybernetic Brain, “Burroughs took cybernetics in directions that would have occurred to no one else.”[28]

Gysin and Burroughs also devised the “Dream Machine,” based on a concept first devised by Al Hubbard, as part of the “set and setting” to accompany LSD experimentation.[29] The Dream Machine was inspired by the experiments of cybernetics pioneer Grey Walter with stroboscopic light, described in The Living Brain. Walter specialized in the very new field of electroencephalography (EEG), the technique of detecting the electrical activity of the brain, brainwaves, using electrodes attached to the scalp. Walter discovered that the flicker or flashing of lights at certain rates synchronized with brain waves to produce strange visions of color and pattern. The Dream Machine was a stroboscopic flicker device that produces visual stimuli, and allows one to enter a hypnagogic state, the experience of the transitional state from wakefulness to sleep.

Gysin and Burroughs also devised the “Dream Machine,” based on a concept first devised by Al Hubbard, as part of the “set and setting” to accompany LSD experimentation.

Burroughs both referred to flicker in his writing and built it into his prose style in his “cut-up” experiments.[30] With Gysin, Burroughs also popularized the “cut-up,” a fusion of magic and literary technique, which was apparently effective. Burroughs’ method was to take photographs and make tape recordings in targeted places, and then play them back at those locations, thus “tampering with actual reality,” and thereby leading to, as he put it, “accidents, fires or removals.” [31] He conducted such an attack on Scientology’s London headquarters, and sure enough, after a couple of months, they were forced to move to another location. Similarly, at a coffee shop in Soho, where he had been subjected to “outrageous and unprovoked discourtesy and poisonous cheesecake,” Burroughs returned half a dozen times to play back the previous day’s recordings and take more photographs, until they were eventually forced to shutdown. [32]

Ginsberg moved to San Francisco where in October 1955 he first performed Howl at Six Gallery, in which he memorialized the experience of Burroughs and his fellow Beats writing that he saw the “best minds” of his generation “dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix.” Ginsberg’s reading was received with great acclaim by his audience, and marked the beginning of what was to be later called the San Francisco Renaissance, as well as the beginning of Ginsberg’s fame as a writer.

San Francisco Renaissance

Allen Ginsberg and A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada in San Francisco (1967)

Sri Aurobindo (1872 – 1950)

Allan Watts (1915 – 1973)

In the mid-1950s, the central figures of the Beat Generation, with the exception of Burroughs, ended up in San Francisco, where they became associated with the San Francisco Renaissance. The key personality of the San Francisco Renaissance was British-born philosopher and friend of Aldous Huxley, Allan Watts, who was also introduced to LSD by Bateson, and served as a consultant on Bateson’s schizophrenia project.[33] Watts became a popularizer of Zen Buddhist philosophy and at the same time founded the Pacifica FM radio stations, which were among the first to push the British-imported rock of The Rolling Stones, The Beatles, and the Animals. As a young man, Watts became interested in Buddhism, and sought membership in the London Buddhist Lodge, which had been established by Theosophists, and run by Christmas Humphreys, and which hosted prominent occultists like Nicholas Roerich and Blavatsky’s leading successor, Alice Bailey.

Politically, Watts was also of the right, having also spent his spare time under the tutelage of Dimitrije Mitrinovic, the influential Bosnian mystic from the circles of Alfred P. Orage’s New Age magazine. Watts had been an enthusiastic member of Mitrinovic’s New Britain.[34] New Britain had its origins in the New Europe Group, which had been created in 1931 also under Mitrinovic’s initiative, and which was closely linked to the Adler Society in London. New Britain rejected capitalism and was pledged to social credit, the welfare state, a united Europe, Rudolf Steiner’s Threefold Commonwealth and a resorted Christianity.

D.T. Suzuki (1870 – 1966)

In 1936, Watts attended the World Congress of Faiths at the University of London, where he heard D.T. Suzuki, a Japanese author of books and essays on Buddhism, Zen and Shin that were instrumental in spreading interest in both Zen and Shin to the West, and a frequent speaker at the Eranos Conferences. In 1911, Suzuki married Beatrice Erskine Lane, a Theosophist with multiple contacts with the Bahai Faith both in America and in Japan. In 1920, they joined the Tokyo International Lodge of the Theosophical Society, and D.T. Suzuki was elected president, as revealed in a to the International Secretary of the Theosophical Society in Adyar. Suzuki was one of the key people responsible for the dissemination of Swedenborg’s teachings in Japan. In 1908 and 1911, he travelled to Europe as a guest of the Swedenborg Society and even translated some of the Swedenborg’s work into Japanese. Suzuki also devoted an entire book to Swedenborg, describing him as the “Buddha of the North.”[35] Thanks to a subsidy from the Bollingen Foundation, he was able to afford the trip to Ascona as a guest of honor for the Eranos Conference.[36]

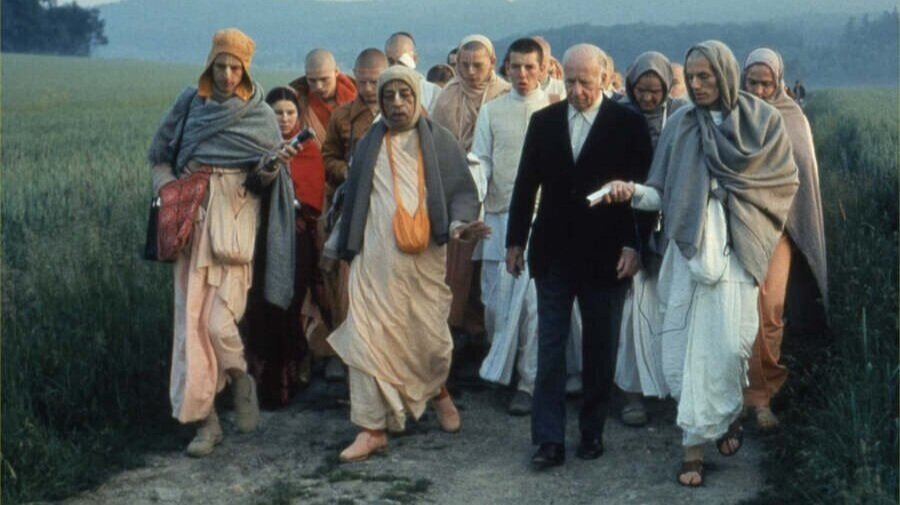

Suzuki wrote approvingly of Japanese fascist and racist policies in Korea, Manchuria and China. An admirer of Nazism and apologist for the Third Reich’s policies against the Jews, Suzuki was a close friend of Gestapo officer Karlfried Graf von Dürckheim, a Rothschild descendant and chief assistant to Joachim von Ribbentrop.[37] Dürckheim helped Suzuki introduce Zen Buddhism to the western world. Durkheim, also a noted expounder of Japanese Zen philosophy in the West, was a committed Nazi and had been a Gestapo officer in Tokyo during the war. Dürckheim was arrested by the Allies during their occupation of Japan and served more than a year in prison as a member of the Gestapo.[38] In 1958, Dürckheim met Alan Watts, who described him as “…a true nobleman—unselfconsciously and by a long tradition perfect in speech and courtesy Keyserling’s ideal of the grand seigneur.”[39]

Former Gestapo officer Karlfried Graf von Dürckheim during a morning walk with Swami Prabhupada 1974 near Frankfurt.

Watts became an Episcopal priest in 1945, but left the ministry by 1950, partly as a result of an extramarital affair and because he could no longer reconcile his Buddhist beliefs. He then became acquainted with Joseph Campbell and his wife, Jean Erdman, as well as the composer John Cage. In early 1951, Watts moved to California, where he joined the faculty of the American Academy of Asian Studies (the precursor to the California Institute of Integral Studies) in San Francisco through which Watts helped popularize Zen among the beatnik scene.

At the academy, Watts taught from 1951 to 1957 alongside Frederic Spiegelberg, a refugee from Hitler’s Germany and Stanford University professor of Asian religions, whose teachers included a cross-section of the German Conservative Revolution and the Eranos conferences, such as Rudolf Otto, Paul Tillich, Martin Heidegger and Carl Jung and like Joseph Campbell. Spiegelberg reported on the 1936 Eranos conference in the Europäische Revue, edited by Prince Karl Anton Rohan, founder of the Kulturbund. Spiegelberg was one of the participants at the seminars on yoga given by Jung and SS member Jakob Wilhelm Hauer at the Psychological Club in Zurich. In India he had visited Sri Aurobindo and Sri Ramana Maharshi. In 1951, Spiegelberg invited Haridas Chaudhuri, a disciple of Aurobindo, to join the staff. From 1956, he also taught at the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich. He also wrote a book, heavily influenced by Suzuki, on the art of Zen, with a foreword by the Eranos lecturer Herbert Read. He was also the author of a book on alchemy, which he illustrated with magical sigils from the sixteenth-century Kabbalistic-magical text Liber Raziel, attributed to Eleazar ben Juda ben Kalonymos, known as Eleazar of Worms.[40]

While Watts was noted for an interest in Zen Buddhism, his reading and discussions delved into Vedanta, “the new physics,” cybernetics, semantics, process philosophy, natural history, and the anthropology of sexuality. In 1957, Watts published one of his best-known books, The Way of Zen. Drawing on the lifestyle and philosophical background of Zen, Watts introduced ideas drawn from general semantics directly from the writings of Alfred Korzybski, and also from Norbert Wiener’s early work on cybernetics, which had recently been published. Watts offered analogies from cybernetic principles possibly applicable to the Zen life. The book sold well, eventually becoming a modern classic, and helped widen his lecture circuit. In 1958, Watts toured parts of Europe with his father, and met Carl Jung.

Watts taught that society imposed “double binds,” or moral demands that were illogical or contrary to one’s true self, and which therefore produced frustration and neurosis, or what Buddhists calls dukkha. The idea was used by Bateson and his colleagues as the suggested basis for schizophrenia. According to Alan Watts, the double bind has long been used in Zen Buddhism as a therapeutic tool. The Zen Master purposefully imposes the double bind upon his students, hoping that they achieve enlightenment (satori). One of the most prominent techniques used is called the koan, a paradoxical question, to lead the student to realize the impossibility of achieving truth, but only to live it intuitively.[41]

Merry Pranksters

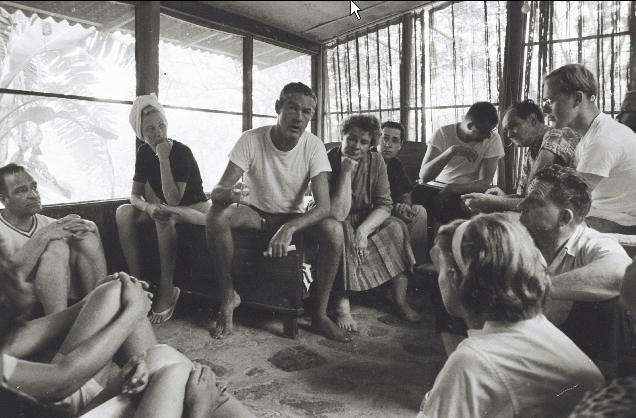

Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters on their bus Further.

Kenneth Kesey (1935 – 2001), leader of the Merry Pranksters and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

The foremost among Gregory Bateson’s Palo Alto recruits was mental patient turned author Ken Kesey. Along with Robert Hunter, who later became lyricist for the Grateful Dead, Kesey was given LSD by Dr. Leo Hollister at Stanford. It is from that point that it was said to have spread “out of the CIA’s realm.”[42] Beginning in 1959, Kesey had volunteered as a research subject for medical trials financed by the CIA’s MK-Ultra. Kesey wrote many detailed accounts of his experiences with drugs, both during the MK-Ultra study and in the years of private experimentation that followed. Kesey’s role as a medical guinea pig inspired him to write One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in 1962.

Kesey continued experimenting on his own and involved many close friends who collectively became known as “The Merry Pranksters.” Together they helped shape the counterculture of the 1960s, when they embarked on a cross-country voyage during the summer of 1964 in a psychedelic school bus named “Further.” The Pranksters also created a direct link between the 1950s Beat Generation and the 1960s psychedelic scene: the bus was driven by Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg was onboard for a time, and they dropped in on Jack Kerouac.

The name recalls The Mad-Merry Pranks of Robin Goodfellow attributed to Ben Jonson (1572 – 1637). Kesey was inspired by the “true fool natural” written about by Robert Armin, the leading comedy actor with Shakespeare’s Lord Chamberlain’s Men. When asked about the connection between Kesey the magician-prankster and his writing, he answered: “The common denominator is the joker. It’s the symbol of the prankster. Tarot scholars say that if it weren’t for the fool, the rest of the cards would not exist. The rest of the cards exist for the benefit of the fool.”[43]

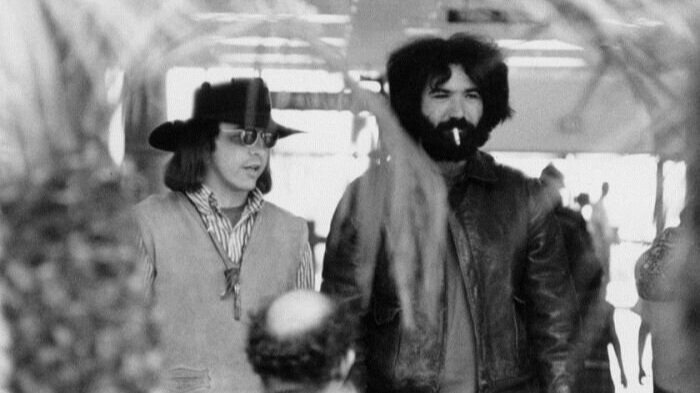

The first show of the Grateful Dead under that name took place in 1965 at one of Kesey “Acid Tests.” These were a series of parties centered entirely around the advocacy and experimentation with LSD, later popularized in Tom Wolfe’s 1968 book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Jerry Garcia, the band’s leader grew up in Menlo Park, site of the Tavistock-affiliated Stanford Research Institute, which conducted extensive intelligence operations for the CIA, particularly experiments into telepathy and remote viewing. Fellow band member Bill Kreutzmann as a teenager met Aldous Huxley at his high school who encouraged him in his drumming. Another member, Bob Weir is a member of the Bohemian Club, and has attended and performed at the secretive club’s annual bacchanal.[44]

Psychedelic icon Owsley “Bear'“ Stanley (left) in 1969 with the Grateful Dead's Jerry Garcia.

It was also at one of these parties that the members of the Grateful Dead met Owsley Stanley, or “Bear,” who was the primary LSD supplier to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, and became the band’s soundman.[45] At the age of fifteen, Owsley had voluntarily committed himself to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington DC. As Colin Ross explained in The CIA Doctors, it was there that Dr. Winfred Overholser Sr. funded LSD research through the Scottish Rite Committee and was at the center of the mind control network.[46] St. Elizabeth’s is also where presidential assailants, serial killers or other federal cases are kept, such as Ezra Pound and John Hinckley, Jr. who shot Ronald Reagan.

Nevertheless, Owsley attended the University of Virginia for some time, and after a stint in the US Air Force beginning in 1956, he later moved to Los Angeles, where he worked at Pasadena’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, founded by Jack Parsons.[47] Leary said of Owsley: “I’ve studied with the wisest sages of our times: Huxley, Heard, Lama Govinda, Sri Krishna Prem, Alan Watts—and I have to say that AOS3, college flunkout, who never wrote anything better (or worse) than a few rubber checks, has the best up to date perspective on the divine design than anyone I’ve ever listened to.”[48]

Millbrook Estate

Leary’s Hitchcock Estate in Millbrook, New York.

After hearing about Leary’s Psilocybin Project at Harvard, Ginsberg asked to join the experiments. In 1964, Ginsberg joined Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters on a bus driven by Neal Cassady during the journey to Timothy Leary’s psychedelic research center at the Hitchcock Estate in Millbrook, New York. Inebriated by an idealism of the transformative possibilities of these drugs, Leary had become frustrated with the rigors of academia and wildly reckless in his experimentation and proselytism for their use, which brought him into conflict with the administration at Harvard. When other professors in the Harvard Center for Research in Personality raised concerns about the legitimacy and safety of Leary’s experiments, he was ultimately fired. Leary declared to David McClelland, the founding board of the Harvard Psilocybin Project, “We’re through playing the science game.” Instead, as Jay Stevens described in Storming Heaven: LSD & The American Dream, “they were going to play the social movement game, and their chief counter was going to be an organization with a serious-sounding name: The International Foundation for Internal Freedom, IFIF for short.”[49]

After leaving Harvard in 1962, Leary then moved his operations to the Hitchcock Estate in Millbrook, which belonged to the Mellon family, who were key participants in the American Liberty League and the Black Eagle Trust.[50] Ownership of the estate passed from oilman Walter Clark Teagle, president of the Rockefellers’ Standard Oil of New Jersey and then to Tommy Hitchcock Jr. (1900 – 1944), a partner in the Lehman Brothers investment firm.[51] Tommy married Margaret Mellon Hitchcock, the daughter of William Larimer Mellon Sr., the founder of Gulf Oil, and the grandson of Thomas Mellon, the patriarch of the Mellon family. Most prominent among the Mellon family supporters of the American Liberty League was William Larimer Mellon Sr.’s uncle, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon. Andrew’s son was Paul Mellon, who served with the OSS in Europe during World War II, and who was co-heir to one of America’s greatest business fortunes, derived from the Mellon Bank. Paul and his wife Mary were supporters of the Eranos Conferences and founded the Bollingen Foundation, which funded Gershom Scholem’s writing of writing of Sabbatai Zevi the Mystical Messiah.[52] A number of Mellons served in the OSS, notably Paul’s brother-in-law David Bruce, the OSS station chief in London and later American ambassador to England. After the war, a number influential members of the Mellon family maintained close ties with the CIA, and Mellon family foundations have been used repeatedly as CIA fronts. During his tenure as CIA director, Richard Helms was a frequent guest of the Mellons in Pittsburgh.[53]

Genealogy of Mellon Family

Thomas Mellon (patriarch and founder of Mellon Bank) + Sarah Jane Negley

Andrew W. Mellon (Secretary of State, backer of Liberty League)

Paul Mellon (OSS) + Mary Mellon (patron of Eranos Conferences and Bollingen Foundation)

Ailsa Mellon Bruce (established the Avalon Foundation) + David Bruce (OSS, ambassador to England)

James Ross Mellon

William Larimer Mellon Sr. (founder of Gulf Oil) + Mary Hill Taylor

Rachel Mellon Walton

Margaret Mellon + Tommy Hitchcock Jr. (inspired the Great Gatsby)

William Mellon Hitchcock (owner of Millbrook Estate, funded Timothy Leary’s IFIF. Sent by David Bruce to meet with Dr. Stephen Ward of Profumo Affair)

Margaret Mellon "Peggy" Hitchcock

William Larimer Mellon, Jr.

Richard B. Mellon + Jennie Taylor King

Sarah Cordelia Mellon + Alan Magee Scaife

Richard Mellon Scaife (controlled the Sarah Scaife Foundation)

Richard King Mellon

Author F. Scott Fitzgerald modeled two characters in his books on Tommy Hitchcock Jr.: Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby (1925) and the Tommy Barban in Tender Is the Night (1934).[54] Tommy’s children were William Mellon “Billy” Hitchcock, Tommy Hitchcock III, and Margaret Mellon “Peggy” Hitchcock, who became heirs to the Mellon fortune. William Mellon Hitchcock funded Leary and Richard Alpert’s IFIF and later financed an LSD manufacturing operation.[55] Peggy was director of the IFIF, later renamed the Castilia Foundation.[56] In early 1963, when IFIF filed incorporation papers, Leary was designated president, Alpert, director, with Gunther Weil, Ralph Metzner, George Litwin, Walter Houston Clark, Huston Smith, and Alan Watts listed as members of the Board of Directors. “In my opinion,” Alan Harringston wrote in his Playboy article:

…the IFIF people are social revolutionaries with a religious base using these extraordinary new drugs as both sacramental material and power medicine. I think they hope to establish a Good Society in the United States… It may seem ridiculous to take a fledgling group so seriously, but Christ and Hitler started small; all revolutionaries meet initially in ridiculous barns and barrooms. So what is especially minor league about a hotel on the Mexican Coast that sleeps forty?[57]

Leary’s conviction of the possibilities of the powers of psychedelics to open up the mind were derived from mysticism. Like many of the leading LSD evangelists, including Aldous Huxley and Gerald Heard, Leary was strongly influenced by Gurdjieff. Gurdjieff believed that the ascetic practices of monks, fakirs and yogis resulted in the production of psychological substances that produced their religious or mystical experiences. Instead of the torturous practices of these mystics, Gurdjieff proposed that the man who knows the Fourth Way “simply prepares and swallows a little pill which contains all the substances he wants. And in this way, without loss of time, he obtains the required result.”[58] Leary later remarked about receiving a copy of the Fourth Secret Teaching of Gurdjieff:

For the past twenty years, we Gurdjieff fans had been titillated by rumors of this Fourth Book, which supposedly listed secret techniques and practical methods for attaining the whimsical, post-terrestrial levels obviously inhabited by the jolly Sufi Master [Gurdjieff]. We had always assumed, naturally, that the secret methods involved drugs. So it was a matter of amused satisfaction to read in this newly issued text that not only were brain-activating drugs the keys to Gurdjieff’s wonderful, whirling wisdom, but also that the reason for keeping the alkaloids secret was to avoid exactly the penal incarceration which I was enjoying when the following essay was penned.”[59]

Timothy Leary believed he was Aleister Crowley reborn and was supposed to complete the work that Crowley began.[60] His autobiography, Confessions of a Drug Fiend, was a composite of Crowley’s Diary of a Drug Fiend and Confessions of Aleister Crowley. Leary confessed in an interview with Late Night America on PBS:

Well, I’ve been an admirer of Aleister Crowley; I think that I’m carrying on much of the work that he started over 100 years ago. And I think the 60’s themselves you know Crowley said he was in favor of finding your own self and “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law” under love. It was very powerful statement. I’m sorry he isn’t around now to appreciate the glories that he started.

Timothy Leary and Rosemary Woodruff at Millbrook (1967)

Leary was joined Allen Ginsberg, and together they began a campaign of introducing other intellectuals and artists to psychedelics.[61] Ginsberg’s cousin was Macy Conference attendee Oscar Janiger, a University of California Irvine psychiatrist and psychotherapist, known for his LSD research, which lasted from 1954 to 1962, and for having introduced LSD to Cary Grant and Aldous Huxley. Bateson gave LSD to Ginsburg at Stanford University in 1959 under controlled experimental conditions. Following the framework of a typical Grey Walter setup suggested to him by Burroughs, Ginsburg had himself hooked up to EEG machine connected to a flicker stroboscope, while listening to recordings of Wagner and Gertrude Stein. Ginsberg had a bad trip which became the basis of his poem, “Lysergic Acid.” Following his interest in Tibetan Buddhism, Ginsberg travelled to India in 1962 with Gary Snyder, and then met with the Dalai Lama to hear what the thought of LSD.[62]

Leary and Ginsberg shared an optimism for the benefits of psychedelics in helping people “turn on,” and Ginsburg convinced Leary of the idea of recruiting popular artists and intellectuals to take these drugs. Leary would later come right out and say, “From the time that Ginsberg showed up on my doorstep, everything changed. After that, the project was different, my life was different, and I was on a different path.” [63] As pointed out by Peter Conners, author of White Hand Society, about the collaboration of Leary and Ginsberg, Leary began to abandon not only sound scientific methods in his research, getting him fired from his position at Harvard, but started favoring “hip talk and poetic language he was getting from Allen,” which blossomed into his counterculture reputation.[64] Together they began a campaign of introducing other intellectuals and artists to psychedelics.[65]

According to Jay Stevens, author of Storming Heaven, “Anyone who was hip in the 1960s came to Millbrook. On any given weekend there were a hundred people there floating through. Strange New York city types, bohemians, jet setters, German counts. You name it, you could find it at Millbrook.”[66] Among the musicians who visited the estate were Maynard Ferguson, Steve Swallow, Charles Lloyd and Charles Mingus. Other guests included Alan Ginsberg, Alan Watts, psychiatrists Humphry Osmond and R.D. Laing, cartoonist Saul Steinberg, and actress Viva Superstar, a prominent figure in Andy Warhol’s circle in New York City..[67]

In 1964, Leary married fashion model Nena von Schlebrügge. D.A. Pennebaker documented the event in his short film You’re Nobody Til Somebody Loves You. The marriage lasted only a year before von Schlebrügge divorced Leary. In 1967 she married Indo-Tibetan Buddhist scholar and ex-monk Robert Thurman. They were the parents of actress Uma Thurman. During her childhood, their family spent time in the Himalayan town of Almora, Uttarakhand, India, and the Dalai Lama, with whom Robert Thurman has long been close, once visited their home.

At some point in the late 1960s, Leary moved to California and made many new friends in Hollywood. “When he married his third wife, Rosemary Woodruff, in 1967, the event was directed by Ted Markland of Bonanza. All the guests were on acid,” wrote Laura Mansnerus.[68] Leary was also the godfather of Winona Ryder (born Winona Laura Horowitz). Her father, Michael Horowitz, is an author, editor, publisher and antiquarian bookseller who was a close associate of Leary’s. Horowitz is responsible with his wife for the creation of the world’s largest library of drug literature, the Fitz Hugh Ludlow Memorial Library. Ryder’s family friends also included Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and the science fiction novelist Philip K. Dick.

Chögyam Trungpa, founder of the Naropa Institute.

Ginsberg was hired to teach poetry and William Burroughs to teach literature at the Naropa Institute, now Naropa University at Boulder, Colorado, founded by guru Chögyam Trungpa, originator of a radical reformulation of the Shambhala vision. Gerald Yorke, a personal friend and secretary to Aleister Crowley, worked closely with Trungpa.[69] Trungpa had a number of notable students, among whom were Alan Watts, New Age personality José Argüelles, Ken Wilber, David Bowie and Joni Mitchell, who portrayed Trungpa in the song “Refuge of the Roads” in her 1976 album Hejira. Trungpa hired Ginsberg to teach poetry and Burroughs to teach literature at Naropa.

Swinging London

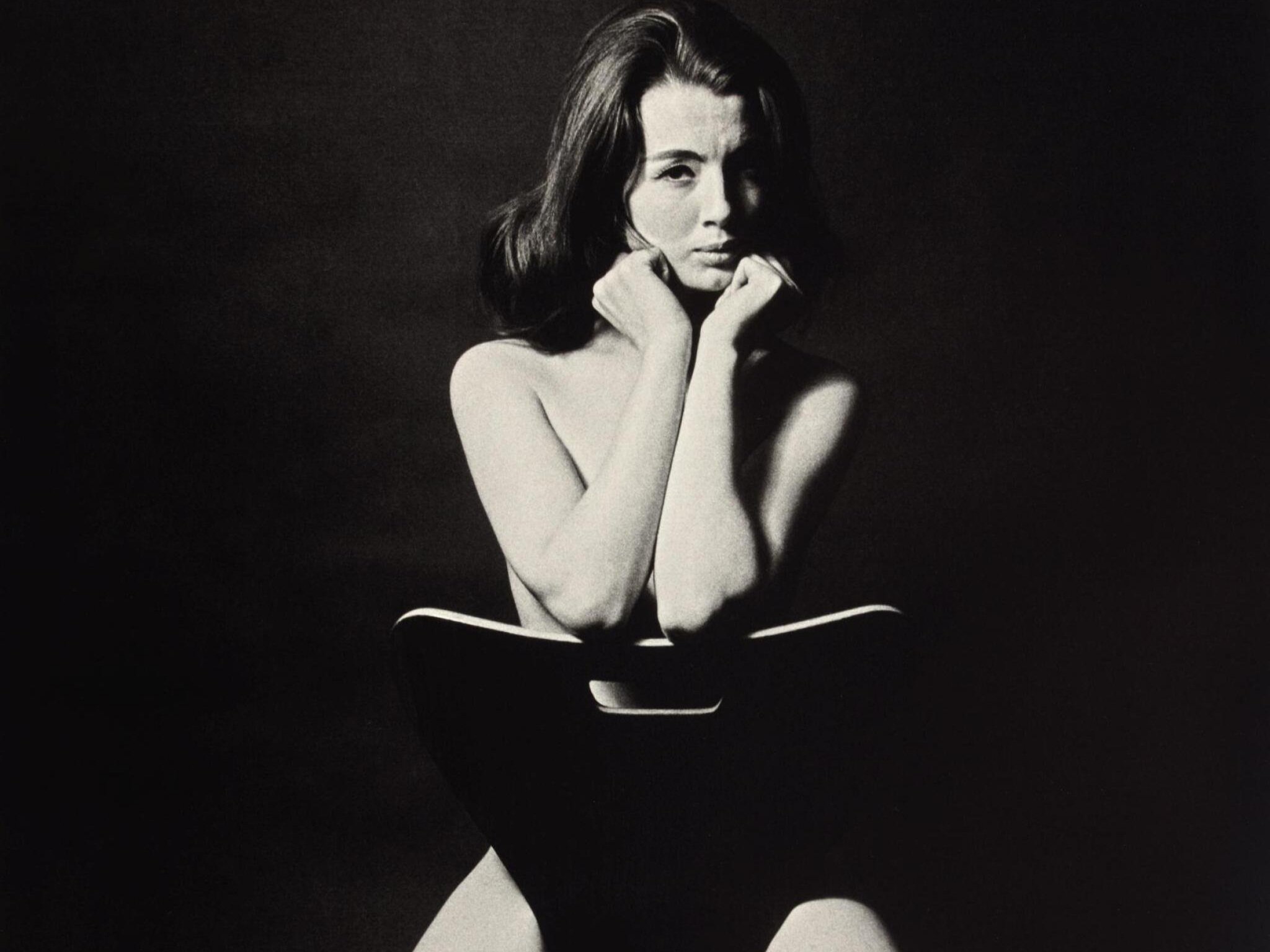

Christine Keeler who was “pimped” by Dr. Stephen Ward, one of the central figures in the Profumo Affair of 1963, at Masonically-themed “black magic” orgies.

President John F. Kennedy appointed David Bruce as ambassador to the United Kingdom. By 1962, Bruce was becoming concerned about allegations swirling about Profumo Affair, and dispatched Thomas Corbally, and William Mellon Hitchcock, his nephew by marriage, to a meeting with Dr. Stephen Ward, who pimped Christine Keeler to John Profumo and Yevgeny Ivanov at Masonically-themed “black magic” orgies, and who claimed to have played during the Cuban Missile Crisis for the British and Soviet governments.[70] Bruce knew of Corbally’s friendship with Ward from Hitchock, whose Center Hitchcock had become involved with another of Ward’s girls, Keeler’s friend Mandy Rice-Davies, in Paris three months earlier.[71] Reportedly, Corbally left this meeting convinced that the allegations surrounding Profumo were true, and informed Bruce, who in turn informed British PM Macmillan. When Bruce did not report back to the US State Department, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover became suspicious that Bruce himself was involved in some kind of international vice ring. Hoover suspected—as did others in the American intelligence community—that one of Keeler’s clients might have been Kennedy himself.[72]

The Profumo Affair turned Keeler into a notorious celebrity, who was memorably photographed sitting naked astride a chair by Lewis Morley, an image that became iconic of Swinging London. The counterculture movement took hold in Western Europe, with London, Amsterdam, Paris, Rome and Milan, Copenhagen and West Berlin rivaling San Francisco and New York as centers of the movement. London saw a flourishing in art, music and fashion. Among its key “pop and fashion exports were the British Invasion headed by The Beatles; Mary Quant’s miniskirt; popular fashion models such as Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton; and the mod subculture. Popular shopping areas such as London’s King’s Road, Kensington and Carnaby Street achieved iconic status. The city became known for “the London sound,” including the Who, the Kinks, the Small Faces and the Rolling Stones.

London was then the scene of a sexually-charged and youthful atmosphere known was Swinging London, a term applied to the fashion and cultural scene of optimism and hedonism that flourished in the city in the 1960s, which featured Members of the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Tony Curtis, Tom Wolfe, John Paul Getty Jr., Andy Warhol, Anita Pallenberg, Michael Cooper, designer Christopher Gibbs, Marianne Faithfull, Dennis Hopper, and John Paul Getty Jr., son of the founder of Getty Oil. William S. Burroughs, who had moved to London in 1960 where he would remain for six years, operated in the upper echelons of the city’s literary elite. He became friendly with Sonia Orwell, and people like Mary McCarthy and Stephen Spender, who were both associated with the CIA’s Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF). Spender was an editor of Encounter, until it was exposed in 1967 as a CIA front.[73]

Timothy Leary and Michael Hollingshead

When Dr. John Beresford received a package of LSD from Sandoz, he in turn gave a gram to Michael Hollingshead, a British-born researcher in psychedelic drugs, known as “the Man Who Turned On the World.” Hollingshead was the Executive Secretary for the Institute of British-American Cultural Exchange in 1961. Hollingshead then contacted Aldous Huxley who suggested he introduce Timothy Leary to the same. After working with Leary on the Harvard Psilocybin Project, and living at Millbrook, Hollingshead was sent to London in September 1965, where he opened the World Psychedelic Center. Being one of only two reliable sources for LSD in London at the time, Hollingshead began welcoming key personalities from the scene, including Roman Polanski, Alex Trocchi, William S. Burroughs, Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, Donovan and the Rolling Stones.

The hub of Swinging London was Indica Books, which was owned by Barry Miles along with Marianne Faithfull’s husband John Dunbar and Peter Asher, whose sister was Paul McCartney’s girlfriend. The bookstore was named after Cannabis Indica, which Crowley equated with the “Elixir Vitae” of the alchemists in The Psychology of Hashish. Dunbar and Faithfull were married on May 6, 1965, with Peter Asher as the best man, and spent their honeymoon in Paris with the Beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso. Indica was supported by Paul McCartney, whom Barry Miles later introduced to the works of Burroughs and Ginsberg, and subjects such as Buddhism and drugs. Miles later wrote Paul McCartney’s official biography, Many Years from Now. Miles has also written biographies of Frank Zappa, John Lennon, William S. Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Charles Bukowski and Ginsberg, in addition to books on The Beatles, Pink Floyd and The Clash, as well as a definitive history of London’s counterculture since 1945, London Calling.

When McCartney and Lennon visited the newly opened Indica bookshop, Lennon had been looking for a copy of The Portable Nietzsche but found a copy of The Psychedelic Experience by Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Ralph Metzner, adapted from the translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead by Walter Evans-Wentz, which was introduced to Leary by Aldous Huxley.[74] Lennon bought the book, went home and followed the instructions exactly as stated in the book. It discussed an “ego death” experienced under the influence of LSD and other psychedelic drugs, supposedly essentially similar to the dying process, and requiring similar guidance. With lyrics adapted from the book, Lennon wrote “Tomorrow Never Knows,” the final track of the Beatles’ 1966 album Revolver.[75]

George Maciunas (1931 – 1978) founder of “neo-Dada” movement Fluxus

Indica hosted a show of Yoko Ono’s work in November 1966, at which she first met John Lennon. Ono was a representative of Fluxus, a “neo-Dada” movement conceived by Lithuanian-born George Maciunas as an attempt to “fuse... cultural, social, & political revolutionaries into [a] united front and action.”[76] At the end of World War II, Maciunas’ family fled to New York where he came into contact with a group of avant-garde artists and musicians centered around avant-garde composer John Cage, at the New School for Social Research in New York, the Frankfurt School in America. Cage’s major influences included Indian philosophy and Zen Buddhism, having attended the lectures of D.T. Suzuki. He also further read the works of Ananda Coomaraswamy. Cage’s work from the sixties features the influences of Marshall McLuhan on the effects of new media, and R. Buckminster Fuller on the power of technology to promote social change. Cage also described himself as an anarchist, and was influenced by Henry David Thoreau.[77]

Robert Fraser (center), also known as “Groovy Bob,” a noted London art dealer who was a pivotal figure of Swinging London.

Sponsoring Ono’s show was a close friend of William S. Burroughs, Robert Fraser, also known as “Groovy Bob,” a noted London art dealer who was a pivotal figure of Swinging London. After being educated at Eton, Fraser joined the Kings African Rifles to serve in Uganda, where, as he boasted to Marianne Faithfull, he had a fling with the infamous Idi Amin, his sergeant major. [78] After a period spent working in galleries in the US, he returned to England and in 1962 he established the Robert Fraser Gallery in London. Fraser’s gallery became a focal point for modern art in Britain and helped to launch and promote the work of many important new British and American artists, including Andy Warhol.

Fraser’s London flat and his gallery were the focal point of Swinging London, featuring guests, in addition to Burroughs, which included Tony Curtis, Tom Wolfe, John Paul Getty Jr., Andy Warhol, Anita Pallenberg as well as members of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, Michael Cooper, designer Christopher Gibbs, Marianne Faithfull, Dennis Hopper (who introduced Fraser to satirist Terry Southern). Fraser also art-directed the cover for The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album, which featured Burroughs, among others, which was created by Peter Blake, a pop artist whose work was exhibited in Fraser’s gallery. Terry Southern, who was featured on The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album, had been part of the Paris postwar literary movement in the 1950s, a companion to Beat writers in Greenwich Village, and also at the center of Swinging London in the 1960s. He worked on the screenplay of Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 film Dr. Strangelove, and his work on Easy Rider helped create the independent film movement of the 1970s. Southern and Burroughs, who had first become acquainted in London, would remain lifelong friends and collaborators.

Terry Southern and The Beatles

John Paul Getty Jr.

Fraser’s guest, John Paul Getty Jr, son of the founder of Getty Oil, named the richest American in 1957. The Getty’s would gain world media attention in 1973 when John Paul Getty Jr’s son was kidnapped and his ear was sent when the grandfather first refused to pay the ransom. In 1966, Getty married Dutch actress Talitha Dina Pol, who was regarded as a style icon of the period, and they became part of the Swinging London scene, becoming friends with, among many others, Mick and his girl-friend Marianne Faithfull. After splitting with Jagger, Faithfull took up with Talitha’s lover, Count Jean de Breteuil, a young French aristocrat who supplied drugs to rock stars such as Jim Morrison of The Doors, Keith Richards, and Marianne herself. According to Marianne, Breteuil “saw himself as dealer to the stars,” and has claimed that he delivered the drugs that accidentally killed Morrison less than two weeks before Talitha’s own death in 1971.[79] Talitha died within the same twelve-month period as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Edie Sedgwick, Jim Morrison and other cultural icons of the 1960s.

From left to right: Judy Marciono Steinberg, Tommy Smothers, John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Rosemary Woodruff Leary and psychologist Timothy Leary at The Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, June 1, 1969 on the day they recorded “Give Peace a Chance.”

Timothy Leary was also present when Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, recorded “Give Peace a Chance” in 1969 during one of their bed-ins in Montreal, and is mentioned in the lyrics of the song. Leary referred to the Beatles as “the four evangelists,” and referring to Sgt. Pepper’s he conceded, “I’m already an anachronism in the LSD movement anyway. The Beatles have taken my place. That latest album—a complete celebration of LSD.”[80] The Beatles famously included Crowley and Timothy Leary among the many figures on the cover sleeve of their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Others figured included H.G. Wells, Aldous Huxley, William S. Burroughs, Hermann Hesse, Alan Watts, Carlos Castaneda, D.T. Suzuki, R.D. Laing, Jorge Luis Borges, Timothy Leary, Madame Blavatsky, J.R.R. Tolkien and Carl Jung.

The album contained a fantasized version of an LSD trip, called “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” As John Lennon later noted, reflecting the intent of the Tavistock Institute, “changing the lifestyle and appearance of youth throughout the world didn’t just happen—we set out to do it. We knew what we were doing.”[81] Leary once recruited Lennon to write a theme song for his California gubernatorial campaign against Ronald Reagan, which was interrupted by his prison sentence due to cannabis possession. Lennon was inspired to come up with “Come Together,” based on Leary’s catchphrase for the campaign.

[1] B.F. Skinner. “Happy and Unhappy Endings.” In Richard Rhodes (ed). Visions Of Technology (Simon and Schuster, 2012).

[2] Cited in Michael Horowitz & Cynthia Palmer (eds). Moksha: Aldous Huxley’s Classic Writings on Psychedelics and the Visionary Experience (Stonehill, 1977), p. 171.

[3] Gregory Bateson. Steps to the Ecology of the Mind (New York: Chandler, 1972).

[4] Gregory Bateson, Don D. Jackson, Jay Haley & John Weakland. “Towards a Theory of Schizophrenia.” Behavioral Science [1956] 1(4): 251-254.

[5] Lee & Shlain. Acid Dreams, p. 54.

[6] Barry Miles. Ginsberg: A Biography. (London: Virgin Publishing Ltd., 2001), p. 233, 242.

[7] 2003 Penguin Modern Classics edition of Junky.

[8] “Hit The Road, Jack.” The Smoking Gun. (September 5, 2005).

[9] Prof. K. Elan Jung, MD. “Sexual Trauma: A Challenge Not Insanity,” A Revolutionary Approach To Treatment & Recovery From Sexual Abuse and PTSD.

[10] Ann Charter. “Allen Ginsberg’s Life” Modern American Poetry. Retrieved from http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/g_l/ginsberg/life.htm

[11] Arnold Lubasch. “Death of Harold Blaeur.” The New York Times. (6 May 1987).

[12] A. Hoffer, M.D., Ph.D. “Dr. Nolan D.C. Lewis 1889-1979” Journal of Orthomolecular Psychiatry, Volume 9 2nd Quarter p. 151-152.

[13] Barry Miles. Ginsberg: A Biography.

[14] Niel Heims. Allen Ginsberg (Infobase Learning, 2013).

[15] Peter Conrad. “Call Me Burroughs: A Life by Barry Miles.” The Guardian (February 9, 2014)

[16] Miles. Call Me Burroughs.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] John Geiger. Nothing Is True-Everything is Permitted: The Life of Brion Gysin (The Disinformation Company, 2005)

[22] Miles. Call Me Burroughs.

[23] Geiger. Nothing Is True-Everything is Permitted.

[24] Miles. Call Me Burroughs.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Felix J. Fuchs. “The Cold War of Metaphors: Cybernetic Fiction and the Fear of Control in the 1960s.” Intensive Seminar in Berlin, (September 12-24, 2011) John-F.-Kennedy-Institut für Nordamerikastudien (Freie Universität Berlin)

[27] J. Geiger. Chapel of Extreme Experience: A Short History of Stroboscopic Light and the Dream Machine (New York: Soft Skull Press, 2003).

[28] Andrew Pickering. The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future (The University of Chicago Press, 2011) p. 11.

[29] Accoding to Myron Stolaroff, in “Hofmann’s Potion.” Documentary by Connie Littlefield, NFB.

[30] Geiger. Nothing Is True-Everything is Permitted. p. 52-53.

[31] Miles. Call Me Burroughs.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Andrew Pickering. The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future (The University of Chicago Press, 2011) p. 174.

[34] Andrew Rigby. “Training for cosmopolitan citizenship in the 1930s: The project of Dimitrije Mitrinovic.” Peace & Change, Vol. 24, No. 3, July 1999, p. 389.

[35] D.T. Suzuki. Swedenborg: Buddha of the North (West Chester, Pa.: Swedenborg Foundation, 1996).

[36] Hans Thomas Hakl. Eranos: An Alternative Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century (New York: Routledge, 2014), p. 196.

[37] Gerhard Wehr. Karlfried Graf Dürckheim: Leben im Zeichen der Wandlung (Freiburg, 1996), p. 75.

[38] Levenda. The Hitler Legacy.

[39] Alan W. Watts. In My Own Way: An Autobiography 1915–1965 (Vintage, 1973), p. 321.

[40] Hakl. Eranos, p. 106.

[41] Alan Watts. Buddhism the Religion of No-Religion (Tuttle Publishing, 1995). p. 62.

[42] Anton Chaitkin. “British psychiatry: from eugenics to assassination,” Executive Intelligence Review, V21 #40, (30 July 2002).

[43] Robert Faggen. “Ken Kesey, The Art of Fiction No. 136.” The Paris Review (Issue 130, Spring 1994

[44] “The gentlemen’s club for the rich and famous that worships a 1980s Page 3 girl | Mail Online.” Dailymail.co.uk.

[45] Peter Herbst. The Rolling Stone Interviews: 1967-1980, (St. Martin’s Press 1989), p. 186.

[46] Colin A. Ross. The C.I.A. Doctors: Human Rights Violations by American Psychiatrists (Manitou Communications, 2006)

[47] Dave McGowan, “Inside The LC.” Part XIV.

[48] Timothy Leary. Politics of Ecstacy, p. 231

[49] Stevens. Storming Heaven, p. 189.

[50] See Chapter 5: In God We Trust; Chapter 11: Golden Triangle.

[51] Carrie Hojnicki. “Timothy Leary’s Hitchcock Estate in Millbrook, New York, May Be the State's Strangest Home.” Architectural Digest (July 28, 2017).

[52] Wasserstrom. “Defeating Evil from Within,” p. 49.

[53] Lee & Shlain. Acid Dreams, p. 190.

[54] O’Neill, Natalie. “Son claims his LI dad was 'Great Gatsby' inspiration – and someone stole his $750G book.” New York Post (March 8, 2013).

[55] Kerry Bolton. Revolution from Above (UK: Arktos Media, 2011) p. 125.

[56] Kerry Bolton. Revolution from Above (UK: Arktos Media, 2011) p. 125.

[57] “in my opinion …” Solomon, p. 78. Cited in Stevens. Storming Heaven.

[58] Peter Ouspensky. In Search of the Miraculous (Harcourt, 1949) p. 50.

[59] Tim Leary. Changing my mind among others, (Prentice-Hall, 1982) p. 192-3.

[60] Robert Anton Wilson. Cosmic Trigger (1977) p. 175.

[61] K. Goffman and D. Joy. Counterculture Through the Ages: From Abraham to Acid House (New York: Villard, 2004), p. 250–252.

[62] Allen Ginsberg. “The Vomit of a Mad Tyger.” Lion’s Roar. (April 2, 2015)

[63] Steve Silberman. “The Plot to Turn On the World: The Leary/Ginsberg Acid Conspiracy.” PLOS (April 21, 2011)

[64] Ibid.

[65] K. Goffman and D. Joy. Counterculture Through the Ages: From Abraham to Acid House. (New York: Villard, 2004), p. 250–252.

[66] Timothy Leary — The Man Who Turned On America. BBC Prime documentary.

[67] Lee & Shlain. Acid Dreams, p. 85.

[68] Laura Mansnerus. “Timothy Leary, Pied Piper of Psychedelic 60s, Dies at 75.” The New York Times (1996-06-01).

[69] Chogyam Trungpa. “The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume 1: Born in Tibet; Meditation in Action; Mudra; Selected Writings.” (Shambhala Publications, 2010), p. 15.

[70] David Livingstone. Ordo ab Chao. Volume Four, Chapter 9: JFK Assassination.

[71] Knightley & Kennedy. An Affair of State, p. 157.

[72] Peter Levenda. Sinister Forces: A Grimoire of American Political Witchcraft, Book Two: A War Gun (Trine Day, 2011).

[73] Lee & Shlain. Acid Dreams, p. 85.

[74] Jonathan Gould. Can’t Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain, and America, (Crown Publishing Group 2007), p. 218.

[75] Peter Brown & Steven Gaines. The Love You Make: An Insider’s Story of The Beatles. (Methuen Publishing, 1980).

[76] George Maciunas. Fluxus Manifesto. (1963).

[77] “John Cage at Seventy.” An Interview by Stephen Montague. American Music, (Summer 1985). Ubu.com.

[78] Miles. Call Me Burroughs.

[79] Robert Greenfield. Exile on Main St.: A Season in Hell with the Rolling Stones, (DaCapo Press, 2006), pp. 55-56; “True Confessions” (portrait of Marianne Faithfull by Ebet Roberts) Mojo, (September 2014), p. 51.

[80] Stevens. Storming Heaven. p. 345.

[81] Mikal Gilmore. Stories Done: Writings on the 1960s and Its Discontents (New York: Free Press, 2008) p. 154

Volume Four

MK-Ultra

Council of Nine

Old Right

Novus Ordo Liberalism

In God We Trust

Fascist International

Red Scare

White Makes Right

JFK Assassination

The Civil Rights Movement

Golden Triangle

Crowleyanity

Counterculture

The summer of Love

The Esalen Institute

Ordo ab Discordia

Make Love, Not War

Chaos Magick

Nixon Years

Vatican II

Priory of Sion

Nouvelle Droite

Operation Gladio