33. The Anti-Semitic League

Glorious Pearls

Abdul Baha’s father, Bahaullah, was exiled from their native Iran, and the family established their residence in Baghdad in Iraq, where they stayed for ten years, until they were later called by the Ottoman state to Istanbul before going into another period of confinement in Edirne and finally the prison-city of Akka, where he remained a prisoner until the Young Turk Revolution freed him in 1908 at the age of 64. The prestige of the Bahais in Ottoman Palestine was enhanced through Abdul Baha’s friendly relations and connections from the 1870s onwards with some Ottoman officials and of the dissident Young Ottoman movement, and later among the liberal Young Turks, including Namik Kemal, Ziya Pasha and Midhat Pasha.[1] Additionally, Abdul Baha was accused by Ottoman officials in Palestine of buying land for the Zionists in the 1890s.[2]

The Ottoman authorities were reporting that committees under the supervision of Mohammed Abduh, then the Grand Mufti of Egypt, were attempting to spread the “Babi [Bahai]” and “Wahhabi [Salafi] sects.”[3] By the 1890s, the Bahai cult was gathering momentum, especially in Iran.[4] As late as 1884, Jamal ud-Din al Afghani was continuing to attempt to maintain good relations with the Bahai community, sending issues of al-Urwa from Paris. In a letter to Afghani around 1877, Abdul Baha wrote:

I read your splendid article printed in the newspaper Misr, which refuted some English newspapers. I found your replies in accord with prevailing reality, and your eloquence aided by brilliant proof. Then I came across a treatise by Midhat Pasa, the contents of which support your correct and magnificent article. So, I wanted to sent it along to you.[5]

By 1900, Bahais probably numbered between 50,000 and 100,000, in a population of 9 million.[6] Browne went so far as to proclaim that the Bahais were the wave of the future of the Middle East.[7] In 1892, in Persia and the Persian Question, Lord Curzon reported on what he regarded to be the astounding success of the Bahai faith:

It will thus be seen that, in its external organisation, Babism has undergone great and radical changes since it first appeared as a proselytising force half a century ago. These changes, however, have in no wise impaired, but appear, on the contrary, to have stimulated, its propaganda, which has advanced with a rapidity inexplicable to those who can only see therein a crude form of political or even of metaphysical fermentation. The lowest estimate places the present number of Babis in Persia at half a million. I am disposed to think, from conversations with persons well qualified to judge, that the total is nearer one million. They are to be found in every walk of life, from the ministers and nobles of the Court to the scavenger or the groom, not the least arena of their activity being the Musulman priesthood itself. It will have been noticed that the movement was initiated by siyyids, hajis, and mullas—i.e. persons who, either by descent, from pious inclination, or by profession, were intimately concerned with the Muhammadan creed; and it is among even the professed votaries of the faith that they continue to make their converts. Many Babis are well known to be such, but, as long as they walk circumspectly, are free from intrusion or persecution. In the poorer walks of life the fact is, as a rule, concealed for fear of giving an excuse for the superstitious rancour of superiors. Quite recently the Babis have had great success in the camp of another enemy, having secured many proselytes among the Jewish populations of the Persian towns. I hear that during the past year they are reported to have made 150 Jewish converts in Tihran, 100 in Hamadan, 50 in Kashan, and 75 per cent of the Jews at Gulpayigan.[8]

According to Shahbazi, “the phenomenon of crypto-Jews (the Anusim) and their role in the genesis and spread of Babism and Bahaism is an important factor in the development of contemporary Iran.”[9] As Shahbazi explained:

The Bahai sect is not a religion in the traditional meaning of the word. It is a very well-organized, centralized and secretive sect that has a record of almost a century and a half of undercover activities, including the infiltration of government institutions and political organizations, and the creation of powerful and influential secret lobbies. No other Iranian political organization can be compared to the Bahai sect.[10]

Shahbazi also claims that it was not Muslims who converted to the Babi and Bahai faith but crypto-Jews who had merely assumed Muslim names.[11] Arsalan Geula, author of Iranian Baha’is from Jewish Background: A Portrait of an Emerging Baha’i Community, notes that large numbers of Iranian Jews at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century converted to the Bahai faith, including in some cases entire extended families.[12] More than 5,000 Jews, mainly from Hamadan, Kashan, Arak, Shiraz, and Tehran alone seem to have converted to the Bahai faith.[13] Hakim Nur Mahmud (1822 – 1899), the most famous Jewish physician of the nineteenth century, was sympathetic to the Bahai religion, and a good number of his descendants openly professed the faith. The earliest Jewish converts were converted by Bahais of Muslim origin, but eventually these Jewish converts went on to convert not only Jews but also Muslims to the new faith. These included Ibn-i-Asdaq (1830 – 1928), and Mirza Abu’l-Fadl (1844 – 1914), who was educated at Dar ul-Funun, and become one the foremost Bahai scholar who helped spread the religion in Egypt, Turkmenistan, and the United States. A substantial number of Jadid al-Islam, Jews who were forced to convert to Islam in Mashhad in 1839, subsequently converted to the Bahai faith and played significant roles in the development of major centers of Bahai religion in Iran, Central Asia. In addition to corresponding with Bahaullah or Abdul Baha, some early Jewish converts undertook the journey to Haifa in Palestine to meet with them in person.[14]

Afghani also seems to have been able to convert his pupil Abduh to the Bahai faith. Bahais from Iran began establishing themselves in Alexandria and Cairo beginning in the late 1860s. Among them was Mirza Abu’l-Fadl, who established an informal circle of students drawn mostly from Al-Azhar. Over the next few years, Abu’l-Fadl converted more than fourteen students and teachers from Al-Azhar to the Bahai faith. When news arrived that Afghani’s Babi co-conspirators were involved in the assassination of Nasser ad-Din Shah in 1896, many Shiah Iranian expatriates called for a retaliatory massacre of the Bahais in Egypt. It was then that Abu’l-Fadl was asked to write an article about the Babi-Bahai movement for the secular-minded journal al-Muqtata, thereby bringing attention to the movement to intellectuals throughout the Arab world.[15]

While he and Abduh were in exile in Paris, Afghani mailed a copy of al-Urwah al- Wuthqa to Bahaullah in Akka. Abduh later taught in Beirut where the met Abdul Baha, and the two struck up a very warm friendship, and agreed with his one-world philosophy.[16] Rashid Rida reported that Abdul Baha attended Abduh’s study sessions several times during visits to Beirut in the late 1880s, and the two corresponded after Abduh’s return to Cairo.[17] Rida disapproved of the friendship, and challenged him to explain why he associated with Abdul Baha. Abduh replied: “This sect is the only one which works for the acquisition of arts and sciences among the Muslims, and there are scholars and sages among them.”[18] When Rida related that he had heard of Abdul Baha’s extensive knowledge of religious science and his diplomatic and oratorical skills, Abduh responded: “Yes, ‘Abbas Effendi [Abdul Baha] is more than that. Indeed, he is a great man; he is the man who deserves to have that epithet applied to him.”[19]

Additionally, Abduh expressed agreement with Abu’l-Fadl’s argument that the expansion of the Bahai faith demonstrated its truth.[20] Rida reported in his biography of Abduh that when Abu’l-Fadl’s ad-Durar al-bahiyyah (“Glorious pearls”) was published in 1890, the book attracted the favorable attention of prominent Muslim intellectuals like Shaykh Ali Yusuf and Mustafa Kamil.[21] Between 1889 to 1900, Ali Yusuf launched Al-Mu’ayyad (“The Supporter”), an Arabic daily newspaper published in Egypt, considered to be an anti-imperialist and pan-Islamic publication, which advocated Afghani’s view on ijtihad.[22] The paper also received covert funding from Abbas II of Egypt (1874 – 1944), who succeeded his father Tewfik Pasha.[23] Abbas II, who resented the interference of Lord Cromer, and wanted to regain more of his authority as Khedive, was attracted to the political activism of Mustafa Kamil (1874 – 1908), of the paper’s most significant contributors.[24] Like Afghani and Abduh, Kamil wrote articles in Al-Ahram, attacking the British and calling for their evacuation.[25]

Mustafa Kamil, along with Mohammed Farid (1868 – 1919), an influential Egyptian political figure, and several other professional men educated in Egyptian and European schools, became a leader of a revived version of the al-Hizb al-Watani (National Party), which had been part of Afghani’s network of Masonic activity during the Urabi Revolt. The party was revived under the aegis of Abbas II, and with strong ties to the Ottoman government. In the 1890s, the party disseminated propaganda in Europe against the British occupation of Egypt and among Egyptians to back the aegis of Abbas II against the Lord Cromer.[26]

Rida didn’t share his Abduh’s sympathies for the Bahai movement. Curiously, however, Rida uses his denunciations of Bahaism to support his calls for the reform of Islam. Rida had left his native Syria, in present-day Lebanon, in 1897 and moved to Egypt in order to join circle of Abduh, soon to be appointed Grand Mufti. Together, they collaborated on Al-Manar (“The Lighthouse”), the first Muslim periodical to appeal to a pan-Islamic audience, which had a far-reaching influence on the Muslim world.[27] Al-Manar was controversial from the outset. According to a group of Ulama who asked that it be banned in Tunisia in 1904, the journal “had not ceased to undermine, at their foundations, the most essential and least debatable principles of Muslim orthodoxy.”[28] Rida insisted that there were only two means of reform, which consisted of a return to the Quran and the Sunnah, and the other in the recognition of a Mahdi, who would restore the Muslim golden age of the time of Mohammed. Rida countered that the messianic beliefs current among Muslims were detrimental to Islam, and referred to the Babi movement as an example of what harm could result from such a belief. As well, Babism, he stated, attacked independent thought and demanded absolute submission. Rida argued blind obedience to a charismatic leader stemmed Babism which he attributed the Shiah belief in Taqlid.[29]

L’Intransigeant

To further pursue his political activism, Mustafa Kamil spent every summer between 1895 and 1907 in France publicizing his media campaign.[30] From 1895 until his unexpected death in 1908, Kamil wrote many articles and editorials in European newspapers including Le Figaro, L’Éclair, Le Journal des Debats, Revue des Deux Mondes, the Times, and Nouvelle revue. Kamil’s friendship with the French novelist Pierre Loti (1850 – 1923) and the feminist and Theosophist Juliette Adam (1836 –1936) led to him being introduced to much of the French intelligentsia.[31] Adam, editor of the Revue des Deux Mondes, an anti-British French periodical, hosted a literary salon in Paris attended by many prominent French journalists and political figures of the time.

In 1852, Juliette Adam married a doctor named La Messine, and published in 1858 her Idées antiproudhoniennes sur l'amour, la femme et le mariage, in defense of Daniel Stern (pen name of Marie d’Agoult, mother of Cosima Wagner) and George Sand. In 1868, Adam was married for a second time to the lawyer and founder of the Crédit foncier, Antoine Edmond Adam (1816 – 1877). Adam joined the Scottish Rite lodge La Clémente Amitié, at that time the most important lodge of the Grand Orient de France.[32] The lodge lent financial support to Juliette’s la Nouvelle Revue.[33] The lodge also accepted Jules Ferry (1832 – 1893) future minister of public education of the Third Republic, and Émile Littré (1801 – 1881), best known for his Dictionnaire de la langue française, commonly called le Littré.[34] The same lodge would initiate Mirza Malkam Khan in 1873.[35]

In 1877, the lodge had about 250 members, including Leon Gambetta (1838 – 1882), a French lawyer and republican politician who proclaimed the French Third Republic in 1870, and Maurice Joly (1829 – 1878), author of the Dialogue in Hell Between Machiavelli and Montesquieu, a satire in protest against the regime of Napoleon III, enemy of the Carbonari, which purportedly inspired the forgery of the Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. Papus mentioned Adam as early as 1891/92 as a member of his Groupe Independant d’Études Ésoteriques, which he founded after leaving Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society, and always spoke full of praise for her work.[36] Juliette’s salon in Paris, where Gambetta played a leading role, was an active center of opposition to Napoleon III and became one of the most prominent republican circles. There met Wagner’s mother-in-law Comtesse Marie d’Agoult, Louis Blanc, Georges Clemenceau, Gustave Flaubert, and Victor Hugo.

Adam also introduced Kamil to other valuable contacts within the French press.” These contacts included leading French editors and writers such as Edouard Drumont (1844 –1917), editor of La Libre Parole, Ernest Judet (1851 – 1943), editor of Le Petit Journal and L’Éclaire), and Henri Rochefort, founder and editor of L’Intransigeant, which also published articles by Afghani on Mahdism.[37] Rochefort, another rabid opponent of Napoleon III, joined the staff of Le Figaro in 1863. Lydia Pashkov, the girlfriend of James Sanua, Afghani’s collaborator, was a correspondent for Le Figaro in Paris, which by the Okhrana, the Russian secret service.[38] In 1868, when Leo Taxil was only fourteen years old, he was apprehended by the French police during an attempt to reach Belgium to join Rochefort in exile.[39] Rochefort’s L’Intransigeant was a supporter of the Antisemitic League of founded by Drumont in 1889.[40] Beside spreading anti-Semitic propaganda, the League was also anti-Masonry and anti-Communist. Its 1889 foundation was inspired by the success of Drumont’s antisemitic pamphlet La France juive (1886), which proposed an opposition between non-Jewish “Aryans” and Jewish “Semites,” and that finance and capitalism were controlled by the Jews.

Among those whom Afghani met in Paris were the newspaper editors, Georges Clemenceau, then editor of La justice, and Henri Rochefort, who, in fact, devoted several pages to him in his autobiography.[41] Clemenceau (1841 – 1929) was a French statesman who would become prime minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. Clemenceau was director of La Justice, where he published articles by Afghani during his stay in Paris.[42] Rochefort states that he came to know Afghani through certain Egyptian military officers who had taken refuge in France after the fall of Urabi Revolt.[43] According to Rochefort:

I was introduced to an exile, celebrated throughout Islam as a reformer and revolutionary, the Sheikh Jamal ad-Din, a man with the head of an apostle. His beautiful black eyes, full of sweetness and fire, and his dark brown beard which flowed to his belly, gave him a singular majesty. He represented the type of the dominator of crowds. He barely understood French which he spoke with difficulty, but his intelligence which was always awake made up easily enough for his ignorance of our language. Under his appearance of serene repose, his activity was all-consuming.[44]

Afghani also knew Ernest Vauquelin, a French left-wing journalist who wrote for Rochefort’s L’Intransigeant. Afghani is mentioned Vauquelin’s Memoirs of the Egyptian Revolution, which in a appeared in the summer and autumn of 1882, having to do with the events surrounding the Urabi Revolt. Rochefort’s L’Intransigeant published two articles by Afghani in 1883. The first was entitled “Lettre sur l’Hindoustan,” in which he attacked British rule in India, and shared his expectation of a coming insurrection. The second, entitled “Le Mahdi,” and was obviously occasioned by the defeat which the Hicks expedition had suffered under the Mahdi.[45] Vauquelin reports that Afghani had been involved in a Mazzini-inspired group in Istanbuld called Jeune Turque (“Young Turks”), which contributed to his first contact with Freemasonry rather than Egypt. According to Vauquelin, “Having learned in Indian the language of the conquerors, he had studied Greek philosophy in English texts, and from a blending of the doctrines of Plato with the books of the Far East has resulted in the eclectic philosophy which he teaches his disciples.”[46]

Dreyfus Affair

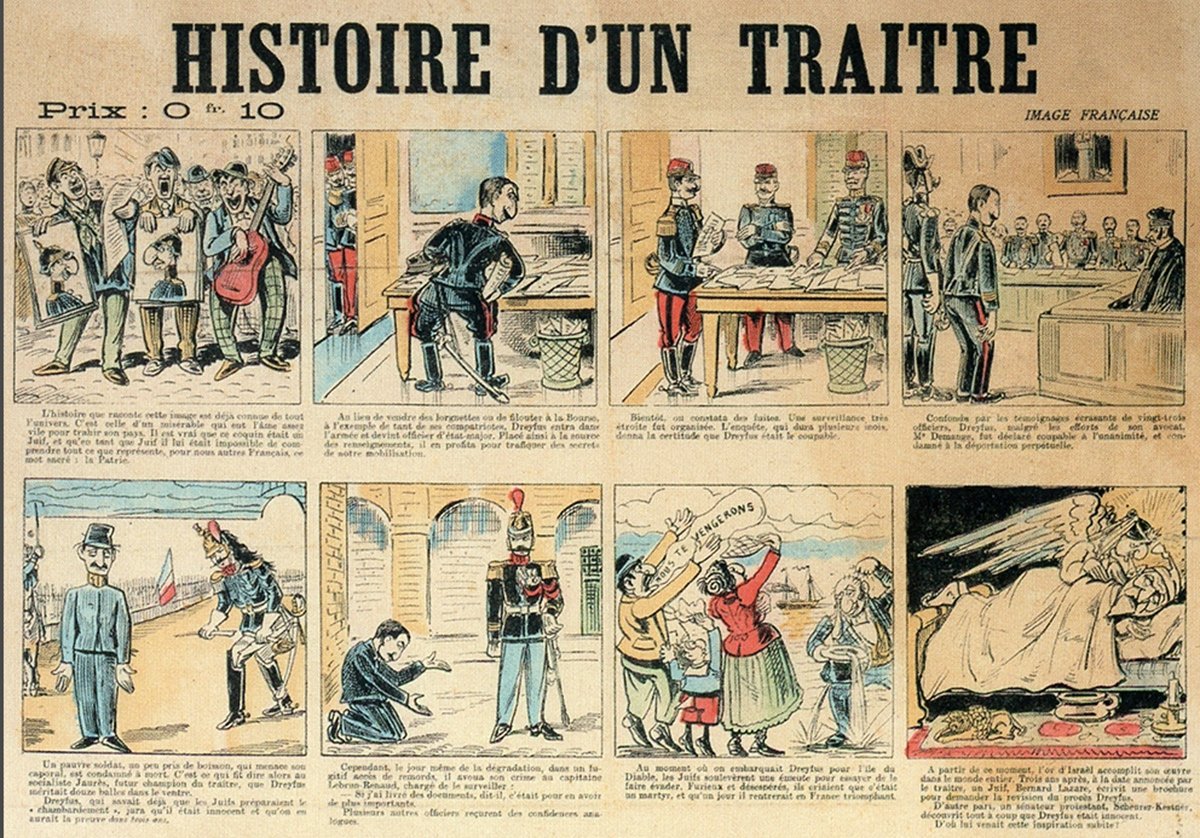

The Antisemitic League was particularly active during the Dreyfus Affair, a notorious anti-Semitic incident in France in which Alfred Dreyfus (1859 – 1935), a Jewish French army captain, was falsely convicted in 1894 of spying for Germany. Subsequently, writer Émile Zola’s open letter J’Accuse...! in the newspaper L’Aurore stoked a growing movement of political support for Dreyfus, putting pressure on the government to reopen the case. With the second trial, the Dreyfus Affair became one of the most controversial and polarizing political dramas in modern French history and throughout Europe, between those who supported Dreyfus, the “Dreyfusards” such as Sarah Bernhardt, Anatole France, Charles Péguy, Henri Poincaré, Marcel Proust and Georges Clemenceau; and those who condemned him, the “anti-Dreyfusards,” such as Édouard Drumont and Ernest Judet, who attacked Zola in Le Petit Journal. Dreyfus was sentenced to life imprisonment and sent overseas to the penal colony on Devil’s Island in French Guiana, where he spent the following five years imprisoned in very harsh conditions. The trial ultimately ended with Dreyfus’ complete exoneration in 1906.

The Antisemitic League was also supported by the daily La Cocarde, edited in 1894 and 1895 by Maurice Barrès (1862 – 1923), a leading mouthpiece of the Anti-Dreyfusard side.[47] Barrès was one of the founding members of the Martinist Order along with Papus. Barrès was a close associate of Gabriele d’Annunzio (1863 – 1938), Grand Master of the Scottish Rite Great Lodge of Italy.[48] In 1901, d’Annunzio and Ernesto Ferrari, the Secretary of the Grand Master of the Grande Oriente of Italy, founded the Università Popolare di Milano (“Popular University of Milan”), located in Via Ugo Foscolo.[49] It was Ferrari’s trip to Istanbul in 1901 that inspired the founding of the Macedonia Risorta, the parent lodge of the Young Turk movement.[50]

Barrès was the first to coin the term “national socialism” in 1898, an idea which then quickly spread throughout Europe. Barrès was close to Charles Maurras (1868 – 1952), founder of the monarchist party Action Française, a movement and journal to serve as a nationalist reaction against the intervention of left-wing intellectuals on the Dreyfus Affair. Henri Vaugeois (1864 – 1916) and Maurice Pujo (1872 – 1955), the original founding members of Action Française, had belonged to l’Union pour l’Action Morale (“Union for Moral Action”), founded in 1893 by Paul Desjardins (1859 – 1940), a French professor, journalist and Synarchist, and a supporter of Dreyfus.[51] The Union split during the Dreyfus affair, giving rise to L’Union pour la Vérité (“Union for Truth”), led by Desjardins, and the Action Française being established by Vaugeois and Pujo in 1889.[52]

On December 16, 1904, Marcel Proust (1871 – 1922) wrote to an old friend from schooldays, Robert Dreyfus, the brother of the Jewish officer Alfred Dreyfus (1859 – 1935), “Here I am, Gobinian. He’s all I think about.”[53] Robert Dreyfus, together with Proust, was one of the leading campaigners for his brother’s release from Devil’s Island. Nevertheless, in 1909, Robert would publish La vie et prophéties du Comte de Gobineau (“The life and prophecies of the Comte de Gobineau”). “All this may suggest, that” noted Robert Irwin, though Count de Gobineau was a racist, “he may not have been a conventional one.”[54]

The Dreyfus Affair was also important impetus to the Zionist movement, which drew on the same well-spring of racist ideas as the pan-German and völkisch movements. Even the ideas of de Gobineau were enthusiastically received by a few German Zionists before World War I.[55] In 1902, the Zionist newspaper Die Welt, founded by Herzl in 1897, accepted Gobineau’s theories on racial degeneration and the desirability of maintaining racial purity, noting that Gobineau had shared his admiration for the Jews as a strong people who believed in the necessity of maintaining its own racial purity. Elias Auerbach (1882 – 1971) and Ignaz Zollschan (1877 – 1948), central European Zionists during the years before World War I, went so far as to praise much of the racial philosophy of Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Wagner’s son-in-law, who would become highly influential in the pan-Germanic Völkisch movements of the early twentieth century.[56] Herzl opened the Second Zionist Congress in 1898 with the overture from Wagner’s Tannhäuser opera.

Also in 1902, Dreyfuss also wrote an article for Die Welt, titled “Thoughts on Zionism,” which was published earlier in the American Jewish newspaper, New York Journal, where he wrote:

Zionism whether or not it is a reflection of a “spirit of Judaism” that has existed for thousands of years, has nevertheless in the last decade taken on a practical form and the possibility of its realization has come ever closer.[57]

The Dreyfus Affair is considered the catalyst for the “conversion” of Herzl, “which made him realize the impossibility of Jewish existence in Europe,” leading him found the Zionist movement by organizing the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897.[58] As the Paris correspondent for Neue Freie Presse, Herzl followed the Dreyfus affair and claimed the case turned him into a Zionist and that he was particularly affected by chants from the crowds of “Death to the Jews!” However, some modern historians now consider that, due to few mentions of the Dreyfus affair in Herzl’s earlier accounts, and an apparently contrary reference he made in them to shouts of “Death to the traitor!” that he may have exaggerated its influence on him in order to create further support for his cause.[59] Kornberg claims that the influence of the Dreyfus Affair on Herzl was a myth, that Herzl did not feel it necessary to refute and that he also believed that Dreyfus was guilty.[60]

During the Dreyfus affair the French antisemitic Right also labelled the Jewish and leftist intellectuals who defended Dreyfus as “Nietzscheans.”[61] Nietzsche had a distinct appeal for many Zionist thinkers around the start of the twentieth century, most notable being Ahad Ha’am, Hillel Zeitlin, Micha Josef Berdyczewski, A.D. Gordon and Martin Buber, who went so far as to extoll Nietzsche as a “creator” and “emissary of life.”[62] Berdyczewski made a pilgrimage in 1898 to the fledgling Nietzsche-Archiv in Weimar, where Nietzsche, who was by then already insane, was living under the care of his sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche.[63] Chaim Weizmann was a great admirer of Nietzsche, and sent Nietzsche’s books to his wife, adding a comment in a letter that “This was the best and finest thing I can send to you.”[64]

Third Temple

It appears, explains Shavit, that Rida became acquainted with the work of anti-Semites in France.[65] Rida’s first writing on the state of the Jews ensued following the Dreyfus affair early in 1898. Initially, Rida strongly condemned anti-Semitism as a disease and wondered how the French would have responded if a similar injustice had been committed in a Middle Eastern country.[66] He suggested the Dreyfuss affair was motivated entirely by the desire of some newspaper owners to get a hold of Jewish wealth. He also strongly criticized Egyptian newspapers that, in his words, had caught the French anti-Semitic disease and attacked Jews for their financial success, to emphasize that a truly civilized and just society required total equality for all its citizens.[67]

Rida’s initial sympathies for the Jews and condemnations of anti-Semitism were soon to vanish and replaced by increasingly overt anti-Semitic notions of his own. The first description of Zionism in al-Manar appeared weeks after Rida’s writing about the Dreyfus affair, and eight months after the conclusion of the first Zionist Congress. Rida published two extensive articles published in al-Manar in 1898 and 1902 condemning Zionism, making him one of the earliest scholarly critics of the movement.[68] Rida warned that the Jewish people were being mobilized to migrate to Palestine with European backing to establish a Zionist state, and urged Arabs to take action, as he thought the Zionists’ ultimate ambition was to convert al-Aqsa mosque into a synagogue and to cleanse Palestine of all of its Arab inhabitants. Rida wrote that the establishment of a Jewish state was preparation for the arrival of their Messiah, which he equated with the anti-Christ who would be killed by Jesus, the true Messiah in Islam. He believed that the Jews were competent only in the financial sector and required British military backing to make up for their inadequate skills in other areas.[69]

In April 1914, Rida reprinted a text on the Zionist movement that had been published six months earlier in Jorji Zaydan’s al-Hilal monthly journal, which predicted that, given the Zionist political abilities and financial power, a Jewish victory in Palestine was “crystal clear.”[70] After a meeting in the following June, in Cairo, with Rida and Nisim Malul, the Jaffa-based Jewish, pro-Zionist correspondent of the liberal daily al-Muqattam, Malul reported that Rida acknowledged the benefits brought to Palestine by Jewish immigration. He also reported that Rida proposed that Palestine should be “shared” by Jews and Arabs, but warned that the Christian Arabs were the worst enemies of Zionism, and called for Jewish-Muslim cooperation against the Turks.[71]

In the following August, as Europe entered World War I, Rida read in the Jaffa-based newspaper Filastin (Palestine) an accurate translation of the first five sections of “Our Program” by Menachem Ussishkin. The essay insisted that the only way to gain ownership of the lands of Palestine was to purchase them, and that the best opportunity to do so was before, rather than after, an international charter on Palestine was granted to the Jewish people. In response, Rida presented a call for action for the first time, concluding that the use of force, which less than six months earlier he had regarded as a last resort, was now the only viable option.[72]

At the start, Rida’s al-Manar had a small circulation, though any copies entering the Ottoman Empire were confiscated by the government. The material printed in the publication became a concern for the Ottoman authorities, such that in 1906 the court in Tripoli issued an order to arrest wherever he might be, “Rashid Rida… who had escaped to Egypt and is the owner and editor of the ‘vanity filled’ paper, al-Manar, and is suspected of printing traitorous and slanderous items in this sheet of paper.”[73] Al-Manar regularly featured anti-Semitic articles linking the Jews and the Freemasons. Rida believed the Jewish people had created capitalism as a tool of manipulation and that they were attacking religious governments across the world to spread atheism and communism.[74] Rida alleged that the Jews had undermined the power of the Roman Catholic Church in Europe and introduced Freemasonry, through which that they orchestrated the French Revolution and manipulated the Bolsheviks and the Young Turks against the Russian and Ottoman empires. Rida believed that while Freemasonry was founded by both Jews and Christians, the Jews led and dominated the order, and that the term “Freemason” itself referred to the re-construction of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, also known as the Third Temple.[75]

By Rida’s own account, at some point after the Committee of Union and Progress took control of the Ottoman Empire in 1908, he had arranged, through Jewish acquaintances, to meet with one of the Zionist leaders in Egypt. In that meeting, Rida had announced that Arab leaders had learned of the Zionist plan to purchase Palestine from their fellow Freemasons in the Turkish leadership, and he warned that the Arabs intended to resist this plan by force. Thus, the Jews ought to abandon their ambitions for independence and instead reside peacefully, under Arab protection, in Palestine and other Arab countries. Rida claimed his warning caused reverberations at a subsequent Zionist Congress. Rida also disclosed that at some point after the Great War, he had discussed with Chaim Weizmann, “the great leader of Zionism,” the terms for an Arab-Jewish settlement. However, the discussions were abandoned because the Zionists had decided to resort to British military power in their efforts to establish their promised kingdom in Palestine.[76]

While Rida may have regarded the Jews as sophisticated global operators, his perception was that Zionism in the years following the Balfour Declaration was as much a British scheme that exploited the Jews as it was a Jewish scheme that exploited the British. After 1922, his analysis was that the British desired Palestine for its religious significance, having conquered it as a “final Crusade.” He described the British as a cunning nation who had promised Palestine to the Jews in order to gain the support of the Americans against Germany. “Relying on what he had learned from Jamal al-Din al-Afghani,” explains Shavit, “Rida warned against being fooled by the British pretense of democracy: whenever the British exploited a people, he wrote, there were voices in their press and parliament that denounced their government’s action. These voices were a deceit intent on creating hope among the oppressed that the British oppressors would save them from their plight.[77]

[1] Necati Alkan. “The Young Turks and the Baháʼís in Palestine.” In Yuval Ben-Bassat & Eyal Ginio, (eds.). Late Ottoman Palestine: The Period of Young Turk Rule (I.B.Tauris, 2011), p. 260.

[2] Alkan. “The Young Turks and the Baháʼís in Palestine,” p. 262.

[3] Ibid., p. 263.

[4] Dreyfuss. Hostage to Khomeini, p. 116.

[5] Cited in Johnson. Initiates of Theosophical Masters, p. 103.

[6] Cole. “Iranian Millenarianism and Democratic Thought in the 19th Century,” p. 1.

[7] Dreyfuss. Hostage to Khomeini, p. 116.

[8] Lord Curzon. Persia and the Persian Question, vol. 1, pp. 499–500. Retrieved from https://www.bahai-library.com/books/dawnbreakers/footnotes/epilogue/663-1.html

[9] Behnam Gholipour. “Abdollah Shahbazi: The Rise and Fall of a Career Antisemite.” Iran Wire (January 14, 2022). Retrieved from https://iranwire.com/en/religious-minorities/71114/

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Anti-Bahaism in Iran.” Iran Press Watch (March 23, 2009). Retrieved from https://iranpresswatch.org/post/2003/anti-bahaism/

[12] Dominic Parviz Brookshaw. “Explaining Jewish Conversions to the Baha'i Faith in Iran, circa 1870–1920.” Iranian Studies, 45:6 (2012), p. 821.

[13] “CONVERSION iv. Of Persian Jews to other religions.” Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved from https://iranicaonline.org/articles/conversion-iv

[14] Dominic Parviz Brookshaw. “Explaining Jewish Conversions to the Baha'i Faith in Iran, circa 1870–1920.” Iranian Studies, 45:6 (2012), p. 821–822.

[15] Juan Ricardo Cole. “Rashid Rida on the Bahat Faith: A Utilitarian Theory of the Spread of Religions.” Arab Studies Quarterly, 5: 3 (Summer 1983), p. 281.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Johnson. Initiates of Theosophical Masters, p. 103.

[18] Cole. “Rashid Rida on the Bahat Faith,” p. 281.

[19] Ibid., p. 282.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., p. 285.

[22] Indira Falk Gesink. “‘Chaos on the Earth’: Subjective Truths versus Communal Unity in Islamic Law and the Rise of Militant Islam.” The American Historical Review, 108: 3 (2003), p. 727.

[23] “Abbas II (Egypt).” Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-Ak – Bayes, 15th ed. (Chicago, IL. 2010), pp. 8–9.

[24] Wayne S. Vucinich. “Abbas II.” In Johnston, Bernard (ed.). Collier’s Encyclopedia. Vol. I: A to Ameland, 1st ed. (New York, NY: P. F. Collier, 1997).

[25] Ziad Fahmy. “Francophone Egyptian Nationalists, Anti-British Discourse, and European Public Opinion, 1885-1910: The Case of Mustafa Kamil and Ya’qub Sannu’.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 28: 1 (2008), p. 173.

[26] Arthur Goldschmidt. “National Party (Egypt).” Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa. Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/asia-and-africa/middle-eastern-history/national-party

[27] Commins. The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia, p. 137.

[28] Mustapha Kraiem. “Au sujet des incidences des deux séjours de Muhammad ‘Abduh en Tunisie,”; cited in Kramer. Islam Assembled, p. 27.

[29] Cole. “Rashid Rida on the Bahat Faith,” p. 286.

[30] Ziad Fahmy. “Francophone Egyptian Nationalists, Anti-British Discourse, and European Public Opinion, 1885-1910: The Case of Mustafa Kamil and Ya’qub Sannu’.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 28: 1 (2008), p. 173.

[31] Ibid., p. 172.

[32] Osterrieder. “Synarchie und Weltherrschaft,” p. 108.

[33] “La Clémente Amitié.” Retrieved from http://www.mvmm.org/c/docs/loges/clemam.html

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Osterrieder. “Synarchie und Weltherrschaft,” p. 108.

[37] Josep Puig Montada. “Al-Afghânî, a Case of Religious Unbelief?” Studia Islamica, 100/101 (2005), p. 208; Keddie. Sayyid Jamal ad-Din “al Afghani,” , p. 205.

[38] “Paris Okhrana 1885-1905.” Center for the Study of Intelligence. Studies Archive Indexes, vol 10 no 3. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence/kent-csi/vol10no3/html/v10i3a06p_0001.htm

[39] Ruben Van Luijk. Children of Lucifer: The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism (Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 217.

[40] William I. Brustein. Roots of Hate: Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[41] Keddie. Sayyid Jamal ad-Din “al Afghani,” p. 205.

[42] Johnson. Initiates of Theosophical Masters, p. 85.

[43] Les A ventures de ma vie, vol. IV (Paris 1897), pp. 345 ff; cited in Kedourie. “Further Light on Afghani,” p. 193.

[44] Henri Rochefort. Aventures de ma vie, tome 4, p. 345. Cited in Johnson. Initiates of Theosophical Masters, p. 86.

[45] Kedourie. “Further Light on Afghani,” p. 193–194.

[46] Homa Pakdaman. Djamal ad-Din Assadabadi di Afghani, p. 346. Cited in Johnson. Initiates of Theosophical Masters, p. 86.

[47] William I. Brustein. Roots of Hate: Anti-Semitism in Europe Before the Holocaust (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[48] Fulvio Conti. Storia della massoneria italiana. Dal Risorgimento al fascism (Bologna: Il Mulino, 2003).

[49] “Our History – Gabriele D'Annunzio.” unipmi.org (in Italian). Università Popolare di Milano. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20110131104107/http://www.unipmi.org/1/la_nostra_storia_1957302.html

[50] Arslan & Enzo. “The Rebirth of the Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress in Macedonia through the Italian Freemasonry,” p. 102.

[51] Annie Lacroix-Riz. “Interview Annie Lacroix-Riz sur la Synarchie par le Canard républicain.” Retrieved from https://www.historiographie.info/synarchie.pdf

[52] Philippe Oriol. L’Histoire de l'affaire Dreyfus de 1894 à nos jours (Les Belles Lettres, 2014), p. 827.

[53] Robert Irwin. “Gobineau, the Would-Be Orientalist.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 26: 1/2 (2016), p. 321.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Nicosia. The Third Reich and the Palestine Question, p. 18.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Cited in Jess Olson. “The Dreyfus Affair in Early Zionist Culture.” In Revising Dreyfus (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2013), p. 315.

[58] Steven Beller. Herzl (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1991).

[59] Henry J. Cohn. “Theodor Herzl’s Conversion to Zionism.” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 32, No. 2 (April, 1970), pp. 101-110.

[60] Kornberg. “Theodor Herzl: A Reevaluation.” Journal of Modern History, Vol. 52, No. 2 (June, 1980), pp. 226–252.

[61] A.D. Schrift. Nietzsche’s French Legacy: A Genealogy of Poststructuralism (Routledge, 1995).

[62] Jacob Golomb (ed.). Nietzsche and Jewish culture (Routledge, 1997), pp. 234–35.

[63] Benjamin Silver. “Twilight of the Anti-Semites.” Jewish Review of Books (Winter 2017). Retrieved from https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/2397/twilight-of-the-anti-semites/#

[64] Kaufmann Walter. Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist (Princeton University Press, 2008).

[65] Uriya Shavit. “Zionism as told by Rashid Rida.” Journal of Israeli History: Society, Politics and Culture, 34: 1 (2015), p. 25.

[66] Ibid.

[67] “Al yahud fi Faransa wa fi Misr” (The Jews in France and Egypt). al-Manar, 1: 4 (1898), pp. 53–55; cited in Shavit. “Zionism as told by Rashid Rida,” p. 26.

[68] Emanuel Beska. “Responses of Prominent Arabs Towards Zionist Aspirations and Colonization Prior to 1908.” Asian and African Studies, 16:1 (2007), pp. 35–40.

[69] Gilbert Achcar. The Arabs and the Holocaust: The Arab-Israeli War of Narratives (London, UK: Actes Sud, 2010), pp. 115–116.

[70] “Filastin: Ta’rikhuha wa-a’tharuha: Ahwaluha al-ijtima‘iyya” (Palestine: Its history and remnants: The social conditions), al-Hilal 22: 7 (April 1, 1914), pp. 513–21; cited in Shavit. “Zionism as told by Rashid Rida,” p. 31.

[71] Mandel. The Arabs and Zionism, p. 193; cited in Shavit. “Zionism as told by Rashid Rida,” p. 31.

[72] “Al-brughram al-Sahyuni al-siyasi,” p. 808; cited in Shavit. “Zionism as told by Rashid Rida,” p. 32.

[73] Tauber. “Rashid Rida as Pan-Arabist before World War I,” p. 103.

[74] John McHugo. A Concise History of the Arabs (New York, NY: The New Press, 2013), pp. 162–163.

[75] Shavit. “Zionism as told by Rashid Rida,” pp. 24, 29, 30, 34, 38.

[76] “Thawrat Filastin: Asbabuha wa nata’ijuha” (The revolution in Palestine: Causes and outcomes) pt. 1, al-Manar, 30: 5 (November 1, 1929), pp. 391–92; cited in Shavit. “Zionism as told by Rashid Rida,” p. 34.

[77] “Al-rihla al-urubiyya” (pt. 4), 444–46; cited in Shavit. “Zionism as told by Rashid Rida,” p. 35.

Divide & Conquer

Volume one

introduction

Harut and Marut

The Lost Tribes of Israel

The Doors of Ijtihad

Old Man of the Mountain

Knights of the Temple

The Rosy Cross

Mason Kings

The Moravian Church

The Lost Word

The Society of the Dilettanti

Unknown Superiors

The Mixed Multitude

Romantic Satanism

The Palladian Rite

The Forty-Eighters

The Ottoman Empire

The British Raj

The Orphic Circle

The Bahai Faith

The Valleys of the Assassins

The Orientatlists

The Iranian Enlightenment

The Brotherhood of Luxor

Neo-Vedanta

The Mahatma Letters

Young Egypt

The Young Ottomans

The Reuter Concession

The Persian Constitutional Revolution

All-India Muslim League

Al Azhar

Parliament of the Word’s Religions

The Antisemitic League

Protocols of Zion

Der Judenstaat

The Young Turks

Journeys to the West

Pan-Turkism