Hail Santa: The Occult Origins of Christmas

Zagmuk

Christmas is an annual festival observed primarily on December 25 among billions of people worldwide. But there are two Christmas themes celebrated simultaneously. The purpose of Christmas is most popularly associated with the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ. However, at the same time, that theme has become increasingly overtaken by the role of the mythical figure of “Satan Claus,” who has no known association with Christianity. Many are aware that Santa Claus is a modification of Saint Nicholas, but few are aware that this modification took place through the influence of the occult, in order to disguise Santa’s true identity as the ancient pagan dying-god Saturn.

The myth of the dying-god would come to pervade, not only the mystical systems of antiquity, but which would transform Western religion and philosophy. Typically, the dying-god was a usurper, who supplants the original creator god by vanquishing the Dragon, who was leader of a race of giants. The underlying dying-god mythology involved the cycle of the seasons. The dying-god was a representation of the Sun, who dies at the winter solstice (Christmas) and resurrects at the spring equinox, or Easter. Further festivals were timed with the summer solstice (Saint John’s Day), and fall equinox (Halloween, All Hallows’ Eve, or All Saints’ Eve). The dying-god’s goddess-spouse was Venus, the “morning star,” though the two were seen as dual aspects of the same deity. The Latin name for Venus is Lucifer. The dying-god was universally regarded as the god of the underworld, where he ruled over the “spirits of the dead,” as discarnate entities were interpreted to be by many early cultures.

The first to recognize the recurring archetype of the dying-and-rising gods was James Frazer in The Golden Bough, first published in 1890, which has had a substantial influence on European anthropology and thought.[1] The focus of Frazer’s research was to attempt to discover the source of the ancient religious tradition of the killing of the sacred king. In ancient paganism, the king was perceived to be the living embodiment of the dying-god, and therefore the fertility of the land was considered dependent on his health. As the king became frail with old age, the success of crops would become at risk, and it was therefore necessary to execute him to allow him to be succeeded by a more virile heir. Ancient monarchs eventually exercised their influence, such that a replacement, or scapegoat, was put in the king’s place for a time, and allowed to revel in his temporary role, until he was himself sacrificed in the king’s stead, during an annual New Years festival.[2]

The origin of the sacred killing of the king was the Zagmuk, or New Year’s festival, corresponding to our Easter, when Babylonians celebrated the death and resurrection of their chief god Marduk, the patron deity of Babylon, also known as Bel. Three important ceremonies were performed for Bel. These acts of worship were fertility rites, referring to the agricultural cycle of nature, with the death of crops in winter and the return of life in the spring, but were also viewed as actually recreating the cosmos itself. In Uruk the festival was associated with the god An, the Sumerian god of the night sky. Both are essentially equivalent in all respects to the Akkadian Akitu festival.

Zagmuk, which literally means “beginning of the year,” was a Mesopotamian festival celebrating the triumph of Marduk, over the forces of Chaos, symbolized in later times by Tiamat. As the battle between Marduk and Chaos lasts twelve days, so does Zagmuk. The peak of the festival took place on the Spring Equinox.[3] First, the Enuma elish, the Babylonian epic of creation, was read, which recounted when the Anunnaki gods gathered together to find one god who could defeat the gods rising against them. Annunaki, seven judges of the Underworld, the children of the god Anu, who had once lived in heaven but were banished for their misdeeds, are the origin of the numerous accounts of legendary giants, known as the Anakim in Flood story of the Bible, otherwise recognized as the Fallen Angels, or the Titans of Greek mythology.

Marduk answered the Annunaki’s call and was promised the position of head god. Marduk sets out for battle, mounting his storm-chariot drawn by four horses with poison in their mouths and defeats the leader of the Anunnaki gods, who is the Dragon, Tiamat. There was a dramatic representation of the conflict between Marduk and Tiamat, during which the god is vanquished and slain, but is raised from death by magical ceremonies, and eventually overcomes the Dragon. Secondly, the king is brought before the image of Marduk, his insignia are removed, and he is slapped in the face by the high-priest. An omen was taken at this point, that if the blow produced tears, the year would be prosperous and vegetation would grow. Finally, in a ceremony known as a sacred marriage, the king, acting the part of the god, practiced ritual copulation with a priestess, symbolizing the union of the god and the goddess. At the festival’s end, the king was slain. To spare their king, Mesopotamians often utilized a mock king, played by a criminal who was anointed as king before the start of Zagmuk, and killed on the last day.

Saturn

Saturn Devouring His Son by Spanish artist Francisco Goya

The Bible makes numerous condemnations of the ancient Israelites sacrificing their children to another derivation of Baal called Moloch, who was associated with Saturn. As god of the underworld, the dying-god was also a chthonic deity, or god of the Underworld, and therefore typically associated with evil.[4] According to the principles of apotropaic magic, the good god was appeased with good sacrifices, while the evil god required evil ones. The most evil sacrifice was the killing of a child. Rabbinical tradition depicted Moloch as a bronze statue heated with fire into which the victims were thrown. This has been associated with reports by Cleitarchus, Diodorus Siculus and Plutarch, who all mention the burning of children as an offering to Cronus or Saturn, that is to Baal Hammon, the chief god of Carthage. Cronus, also spelled Cronos or Kronos, in ancient Greek religion, is a male deity who was worshipped by the pre-Hellenic population of Greece. In Attica, his festival the Kronia celebrated the harvest and resembled the Roman Saturnalia.

Scholars have now come to acknowledge the striking similarities between Mesopotamian mythology and the works of the greatest of the Greek poets, Hesiod and Homer.[5] Hesiod, believed to belong to the eighth century BC, was the author of the Theogony, a systematization of early Greek mythology. Hesiod’s Theogony outlines a usurper myth, an account of how Zeus became superior following a war against Kronos and the Titans. According to Hesiod, Kronos was the son of Uranus and Gaea, being the youngest of the twelve Titans. After castrating his father, on the advice of his mother, he became the king of the Titans. He took for his consort his sister Rhea, who bore by him Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon, all of whom he swallowed because his own parents had warned that he would be overthrown by his own child. When Zeus was born, however, Rhea hid him in Crete, and when he grew up, Zeus forced Kronos to disgorge his brothers and sisters, waged war on Kronos, and was victorious. According to one tradition, the period of Kronos’ rule was a Golden Age.[6]

The motif that the present rule of the gods came to power by overthrowing an older one is especially Near Eastern. According to M.L. West, “Hesiod’s integration of a dynastic history of this sort with a divine genealogy, starting from the beginning of things and ending with the king of the gods established in glory, has its closest parallel in Enuma elish, a poem of similar length to the Theogony.”[7] The myth of Kronos swallowing his children was compared to the Carthaginian worship of Moloch, or Saturn, by Diodorus:

Among the Carthaginians there was a brazen statue of Saturn putting forth the palms of his hands bending in such a manner toward the earth, as that the boy who was laid upon them, in order to be sacrificed, should slip off, and so fall down headlong into a deep fiery furnace. Hence, it is probable that Euripides took what he fabulously relates concerning the sacrifice in Taurus, where he introduces Iphigenia asking Orestes this question: “But what sepulchre will me dead receive, shall the gulf of sacred fire me have?” The ancient fable likewise that is common among all the Grecians, that Saturn devoured his own children, seems to be confirmed by this law among the Carthaginians.[8]

Like the defeat of Tiamat by Bel, Zeus with his thunderbolts defeats the monster Typhon and has him flung to Tartarus, and Zeus is proclaimed king of the gods.[9] The Titans correspond to the Anakim, or the Anunnaki of the Enuma elish, and to the Hittite Former Gods, the same term used by Hesiod to refer to the Titans, which are twelve in number, the same quantity as the Titans.[10] When the Titan Prometheus stole the fire of the gods, wishing to impart to man what was forbidden him, like the Bible’s Satan, Zeus finally punished the Titans for their insolence by sending the Flood. Of the connection between the myth of Deucalion, the Greek Flood hero, and Noah, according to M.L. West, “this Greek myth cannot be independent of the Flood story that we know from Sumerian, Akkadian, and Hebrew sources, especially from Atrahasis, the eleventh tablet of the Gilgamesh epic, and the Old Testament.”[11]

Saturnalia

Saturnalia by Antoine Callet (1783)

As reported by Strabo, the Persians celebrated a festival called Sacaea, named after the Sacaea, which derived from the ancient Babylonian Zagmuk, which involved sacred the killing of the king. According to Strabo, the Sacaea as it was found in Asia Minor was celebrated alongside the worship of the Persian goddess Anaitis, the mother of Mithras. Strabo describes it as a Bacchic orgy, held at the spring equinox, at which the celebrants were disguised as Scythians, and women drank and reveled together day and night.[12]

In common with Jesus, Mithras was born in a cave surrounded by animals and shepherds at the Winter Solstice in December, dates that had specific astronomical significance. In the Julian calendar, the December 25 was reckoned the winter solstice, and was regarded as the Nativity of the Sun, because from this date the length of the day began to increase, and therefore, was regarded as the day of the rebirth of the Sun-god and the rejuvenation of life. The Gospels, however, say nothing as to the day of Christ’s birth, and accordingly the early Church did not celebrate it. In time, though, the Christians of Egypt had come to regard the sixth of January as the birth of the Savior, and that date gradually spread until, by the fourth century AD, it was universally established in the East. Finally, however, at the end of the third or the beginning of the fourth century AD, the Western Church, which had never recognized the sixth of January as the day of the Nativity, adopted the December 25 as the true date.

The later Roman Empire celebrated the Dies Natalis of Sol Invictus, the “Nativity of the Unconquerable Sun,” on December 25. It was preceded by the Roman festival of the Saturnalia, which according to James Frazer, was an accommodation of a more ancient Babylonian ritual of Zagmuk.[13] The Roman playwright Accius (170 – c. 86 BC) traced the Saturnalia to the ancient Greek festival of the Kronia, dedicated to Cronus.[14] The Saturnalia underwent a major reform in 217 BC, after the Romans suffered one of their most crushing defeats by Carthage during the Second Punic War. Until then, the holiday was celebrated according to Roman custom (Mos maiorum). After consulting the Sibylline books, “Greek rite” (sacra Greaco ritu) or “Greek cults” (Greaca sacra) were adopted, introducing sacrifices, the public banquet, and shouts of “io Saturnalia” that characterized the celebration.[15]

According to the Roman tradition, the oldest collection of Sibylline books, not be confused with the Sibylline Oracles, were compiled about the time of Solon and Cyrus at Gergis on Mount Ida in the Troad. From Gergis the collection passed to Erythrae, where it became famous as the oracles of the Erythraean Sibyl. It would appear to have been this very collection that found its way to Cumae, a Greek colony located near Naples, and from Cumae to Rome. The Cumaean Sibyl was the priestess presiding over the Apollonian oracle at Cumae. Because of the importance of the Cumaean Sibyl in the legends of Rome’s origins as codified in Virgil’s Aeneid, the Cumaean Sibyl became the most famous among the Romans. The story of how the Sibylline Books were acquired by Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, Tarquinius Priscus, the legendary fifth king of Rome who reigned from 616 to 579 BC, is one of the famous mythical elements of Roman history. The books were kept in the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill, where they were consulted only in times of emergency. The Emperor Augustus had them moved to the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine Hill, where they remained for most of the remaining Imperial Period.

In the Saturnalia of Macrobius, the proximity of the Saturnalia to the winter solstice leads to an exposition of solar monotheism, the belief that the Sun (Sol Invictus) ultimately encompasses all divinities as one.[16] The Saturnalia, which is the source of Christmas, was celebrated in honor of Saturn, the origin of Santa.74 The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves. A common custom was the election of a “King of the Saturnalia,” who would give orders to people and preside over the merrymaking. However, as reported by James Frazer, there was a darker side to the Saturnalia. In Durostorum on the Danube, Roman soldiers would choose a man from among themselves to be the Lord of Misrule for thirty days, after which his throat was cut on the altar of Saturm.[17]

Feast of Fools

The Fight Between Carnival and Lent by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in 1559, contrasting two sides of contemporary life, with the inn on the left side and the church on the right.

Priapus, son of Aphrodite by Dionysus

In his book De Occulta Philosophia published in 1531–1533, the German occultist and magician, Henry Cornelius Agrippa, mentioned the Knights Templar—who are revered as the ancestors of Freemasonry—in connection with the survival of Gnosticism, and thus, according to Michael Haag, “thrust the order into the phantasmagoria of occult forces which were subject of the persecuting craze for which the Malleus Maleficarum was a handbook.”[18] According to Agrippa in Chapter 39 of De Occulta Philosophia:

Everyone knows that evil spirits can be summoned through evil and profane practices (similar to those that Gnostic magicians used to engage in, according to Psellus), and filthy abominations would occur in their presence, as during the rites of Priapus in times past or in the worship of the idol named Panor to whom one sacrificed having bared shameful parts. Nor is any different from this (if only it is truth and not fiction) what we read about the detestable heresy of the Knights Templar, as well as similar notions that have been established about witches, whose senile womanish dementia is often caught causing them to wander astray into shameful deeds of the same variety.

The pagan fertility god Priapus was the ugly son of Dionysus and Aphrodite, whose symbol was a huge erect penis, and the Greek, half man—half goat god, Pan. The worship of pan was associated with a Medieval variation of the Green Man, a motif often related to fertility deities found in different cultures throughout the world, such as the Celtic god Cernunnos, Green George, Jack in the green, John Barleycorn, Robin Goodfellow, Puck, and the Green Knight of Grail legend. A more modern version is found in Peter Pan, who enters the civilized world from Neverland, clothed in green leaves. At Temple Church in London, there are twelve carvings of Green Man heads above the portal to the round church, with four foliate shoots growing from the mouths in the shapes of ‘X’.[19] The equivalent of the Green Man in Sufi Islam is Al Khir, “the Green One.”

Depiction of Father Christmas riding on a goat.

The worship of Pan was associated with the survival of the Saturnalia, in the form of the Feast of Fools and Carnival. As in the case of the Bacchanalia, after centuries during which very little is known about the ancient festivals, celebrations like the Saturnalia make their reappearance during the late Medieval period.[20] The popularity of Saturnalia continued into the third and fourth centuries AD, and as the Roman Empire came under Christian rule, many of its customs were recast later celebrations in western Europe occurring in midwinter, particularly traditions associated with Christmas, the Feast of the Holy Innocents, and Epiphany.[21]

The twelve days of Christmas, like the Saturnalia, were marked by massive eating, drinking and game playing and also by rituals of inversion. Present-day Christmas traditions such as the Yule log, Yule goat, Yule boar, Yule singing, and others stem from Yuletide, a twelve-day pagan festival, indicating the month of “Yule” (January). Yule was observed by the historical Germanic peoples, connected to the celebration to the Wild Hunt, the god Odin, and the pagan Anglo-Saxon Modranicht. The Wild Hunt, is a European folkloric motif that typically involved a ghostly or supernatural group of hunters passing in wild pursuit. The hunters may be either elves or fairies or the dead, and the leader of the hunt is often a named figure associated with Odin.[22] The Yule later underwent Christianized reformulation resulting in the term Christmastide. Odin’s role during the Yuletide has been theorized as having influenced concepts of St. Nicholas, and later Santa Claus, in a variety of facets, including his long white beard and his gray horse for nightly rides.[23]

The Devil’s nickname, “Old Nick,” explains Jeffrey Burton Russell in The Prince of Darkness, derives directly from Saint Nicholas, a fourth-century Greek Christian bishop of Myra, a Roman town in what is now south-western Turkey. [24] In 1087, after the Greek Christians of Myra fell under the subjugation of the Muslim Seljuq dynasty, Italian sailors from Bari in Apulia seized part of the Saint Nicholas’ from his burial church in Myra, over the objections of the Greek Orthodox monks. Two years later, Pope Urban II inaugurated a new church, the Basilica di San Nicola, to Saint Nicholas in Bari, and personally placed Nicholas’ relics into the tomb beneath the altar. The remaining bone fragments from the sarcophagus were later removed by Venetian sailors and taken to Venice during the First Crusade. Nicholas’ reputation as a gift-giver grew with time, and during the Middle Ages, often on the evening before December 6, the saint’s feast day, children were bestowed gifts in his honor.

Within these twelve days, December 28, the day on which the Church commemorated the Massacre of the Innocents—Herod’s slaughter of the male infants after Jesus’ birth—was celebrated in part of medieval Europe, notably in France, with a particular ritual inversion known as the Feast of Fools. In England, the Lord of Misrule, known in Scotland as the Abbot of Unreason and in France as the Prince des Sots, was an officer appointed by lot during Christmastide to preside over the Feast of Fools. The historical western European Christmas custom of electing a “Lord of Misrule” have its roots in Saturnalia celebrations.[25] James Frazer claimed that the appointment of a Lord of Misrule comes from an ancient custom known as the “Killing of the King,” such as the one practiced during the Roman celebration of Saturnalia. In ancient Rome, from December 17 to 23 in the Julian Calendar, a man was chosen to mockingly take the place of the king during the feast of Saturnalia. In the guise of the Roman deity Saturn, at the end of the festival, the man was sacrificed.[26]

The Feast of Fools held on or about January 1, particularly in France, in which a mock bishop or pope was elected, ecclesiastical ritual was parodied, and low and high officials exchanged places. A report from the year 1198 noted that at the Feast of the Circumcision in Notre Dame in Paris, “so many abominations and shameful deeds” were committed that the locale was desecrated “not only by smutty jokes, but even by the shedding of blood.”[27] In 1444, a letter from the Theological Faculty of Paris to all the French bishops complained that “even the priests and clerics elected an archbishop for a bishop or pope, and named him the Fools’ Pope.”[28]

Victor Hugo recreated a picturesque account of a Feast of Fools in his 1831 novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame, in which it is celebrated on January 6, 1482 and Quasimodo serves as Pope of Fools. This is shown in Disney’s 1996 animated film version of the novel through the song “Topsy Turvy,” whose lyrics include, “It’s the day the devil in us gets released; It’s the day we mock the prig and shock the priest; Ev’rything is topsy turvy at the Feast of Fools!” Victor Hugo cites Jean de Troyes who in the fifteenth century remarked that what “excited all the people of Paris” on January 6 was the two age-old celebrations of the Feast of the Epiphany and the Feast of Fools. The day included a bonfire on the Place de Grève, a mystery play at the Palais de Justice, and a maypole at the chapel of Braque. The European Carnival (Mardi Gras) also resembles the Saturnalia.[29] The word Carnival is of Christian origin, and in the Middle Ages, it referred to a period following Christmastide that reached its climax before midnight on Shrove Tuesday. Some folklorists have also claimed that Carnival derives from the Bacchanalia and even that it takes its name from the wheeled ship (carrus navalis), which carried the ithyphallic image of the god.[30]

A maypole is a tall wooden pole erected on May Day as a part of various European folk festivals, around which a maypole dance often takes place. May-poles were remnants of the ancient phallic Asherah poles dedicated to the worship of Baal.[31] Phallic symbolism has been attributed to the maypole in the later Early Modern period, as one sexual reference is in John Cleland's controversial eighteenth century erotic novel Fanny Hill: “…and now, disengag’d from the shirt, I saw, with wonder and surprise, what? not the play-thing of a boy, not the weapon of a man, but a maypole of so enormous a standard, that had proportions been observ’d, it must have belong’d to a young giant.”[32]

Lord of Misrule

Christmas revels at Haddon Hall, Derbyshire, as illustrated in volume I (1839) of Mansions of England in the Olden Time, by Joseph Nash. Mummers play while musicians perform in the balcony. Haddon Hall was famous for Christmastide hospitality and feasts during the Twelve Days.

Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626)

Academic drama stems from late medieval and early modern practices of miracles and morality plays as well as the Feast of Fools and the election of a Lord of Misrule, a role inherited from the Saturnalia, dedicated to Saturn, or Satan, believed to be the origin of the twelve days of Christmastide and modern Christmas.[33] The intellectual development of dramas in schools, universities, and Inns of Court in Europe allowed the emergence of the great playwrights of the late sixteenth century.[34] The Inns of Court were professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. The four Inns, established between 1310 and 1357, are Lincoln’s Inn, Gray’s Inn, the Middle Temple and the Inner Temple. The Temples takes their name from the Knights Templar, who originally leased the land to the Temple’s inhabitants (Templars) until their abolition in 1312.[35] After the Templars were dissolved in 1312, their land was seized by the king and granted to the Knights Hospitaller. With the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, the Hospitallers’ properties were confiscated by the king, who leased them to the Inner and Middle Temples until 1573. King James granted the land to a group of noted lawyers and Benchers, including Sir Julius Caesar and Henry Montague, and to “their heirs and assignees for ever.”[36]

At Gray’s Inn, Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626), who is typically celebrated by Masonic historians as having been a Rosicrucian, was a member of the Order of the Helmet,[37] dedicated to the goddess Pallas Athena, who was most often represented dressed in armor like a male soldier, holding a spear in her right hand, with a serpent writhing at her feet, and wearing a Corinthian helmet raised high atop her forehead. Developed in the early seventh century BC, the “Corinthian style” helmet had no ear holes, but had solid nose guard a phallic cap-shaped crown.[38] It is also known as the Cap of Hades, Helm of Hades, or Helm of Darkness. Wearers of the cap in Greek myths include Athena, the goddess of wisdom, the messenger god Hermes, and the hero Perseus. Rabelais called it the Helmet of Pluto,[39] and Erasmus the Helmet of Orcus, a Roman god of the underworld.[40]

In classical mythology, the helmet was also known as the Cap of Invisibility that can turn the wearer invisible. According to Bacon, “the helmet of Pluto, which maketh the politic man go invisible, is secrecy in the counsel, and celerity in the execution.”[41] Thus the members of the Order of the Helmet likewise served “invisible” to the world, much of their labor being published anonymously or under pseudonyms.[42] To signify their vow of invisibility the knights of the order all had to kiss Athena’s helmet.[43] Pallas Athena was known as “the Spear Shaker” or the “Shaker of the Spear,”[44] while the cryptically hyphenated version of the name “Shake-Speares” appeared on the title pages of certain plays of Shakespeare, and on every page of the first edition of his sonnets.[45]

In contrast to Cambridge and Oxford, who produced theatre as a literary study, the London Inns of Court produced theatre as a means of entertainment.[46] Until the end of the seventeenth century, these performances typically took the form of masques written by law students at the Inns of Court. Once the Inns of Court transitioned from masques to plays, the so-called third university served as a cradle for classical English drama. Eventually, by the early seventeenth century, writers such as Ben Jonson and William Shakespeare began producing English comedies at the Inns of Court, thus expanding the range of materials performed.[47]

The style of the plays of Shakespeare, Marlowe and Jonson is referred to as English Renaissance theatre, also known as Elizabethan theatre. Academic drama refers to a theatrical movement that emerged in the mid sixteenth century during the Renaissance. With the rediscovery and redistribution of classical materials during the English Renaissance, Latin and Greek plays began to be restaged.[48] Dedicated to the study of classical dramas for the purpose of higher education, universities in England began to produce the plays of Sophocles, Euripides, and Seneca the Younger (among others) in the Greek and Roman languages, as well as neoclassical dramas.

The Feast of Fools includes mummer plays, folk plays performed by troupes of amateur actors, traditionally all male, known as mummers or guisers. Early scholars of folk drama, influenced by James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, tended to view these plays as survivals of pre-Christian fertility ritual.[49] Mummer refers particularly to a play in which a number of characters are called on stage, two of whom engage in a combat, the loser being revived by a Doctor character. This play is sometimes found associated with a sword dance. Mummers are generally performed seasonally or annually, often at Christmas, Easter or on Plough Monday, more rarely on Hallowe’en or All Souls’ Day, and often with a collection of money, in which the practice may be compared with other customs such as those of Halloween, Bonfire Night, wassailing, pace egging and first-footing at new year.[50] The principal characters are a hero, most commonly Saint George, King George, or Prince George (Robin Hood in the Cotswolds and Galoshin in Scotland), and his chief opponent, (known as the Turkish Knight in southern England), named Slasher elsewhere, and a quack Doctor to restore the slain man to life. Other characters include Old Father Christmas, who introduces some plays, the Fool and Beelzebub or Little Devil Doubt, who collects money from the audience. Despite the frequent presence of Saint George, the Dragon rarely appears although it is often mentioned.

William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616)

Ingrid Brainard argues that the English word “mummer” is ultimately derived from the Greek name Momus, the god of carnivals. In Greek mythology, Momus was the personification of satire and mockery.[51] In Aesop’s fables Momus is asked to judge the handiwork of three gods: a man, a house and a bull. He found all at fault: the man because his heart was not on view to judge his thoughts; the house because it had no wheels so as to avoid troublesome neighbors; and the bull because it did not have eyes in its horns to guide it when charging.[52] For that reason, Plutarch and Aristotle criticized Aesop’s story-telling as deficient, while it was defended by Lucian, who is best known for his tongue-in-cheek style, with which he ridiculed superstition, religious practices, and belief in the paranormal.[53] In Lucian’s The Gods in Council Momus takes a leading role in a discussion on how to purge Olympus of foreign gods and barbarian demi-gods who are lowering its heavenly tone.

Bacon describes the precepts put forward in The Advancement of Learning as based on knowledge ourselves and knowledge of others, citing the example of Momus, who found fault in the human heart for its lack of a window. During the Renaissance, several literary works used Momus as a mouthpiece for their criticism of tyranny, while others later made him a critic of contemporary society. Leon Battista Alberti wrote the political work Momus or The Prince (1446), which continued the god’s story after his exile to earth. Since his continued criticism of the gods was destabilizing the divine establishment, Jupiter bound him to a rock and had him castrated. Giordano Bruno’s philosophical treatise The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast (1584) also harkens to Lucian’s example. There Momus plays a central role in the series of dialogues conducted by the Olympian deities and Bruno’s narrators as Jupiter seeks to purge the universe of evil.[54]

During the reign of Elizabeth I, Gray’s Inn rose in prominence, and that period is considered the “golden age” of the Inn, with Elizabeth serving as the Patron Lady.[55] Gray’s Inn, as well as the other Inns of Court, became noted for the parties and festivals it hosted. In winter 1561, the Inner Temple was the scene of an extraordinary set of revels and a performance of a play called Gorboduc, before Queen Elizabeth, that celebrated the raising of Robert Dudley as the Temple’s “Christmas Prince.” Dudley was granted the role in gratitude for his intervention in a dispute with the Middle Temple over Lyon’s Inn, one of the Inns of Chancery that had historically been tied to the Inner Temple. Dudley’s influence swayed Elizabeth into asking Nicholas Bacon—as Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, and father of Francis Bacon—to rule in favor of the Inner Temple, and in gratitude the Parliament and Governors of the Inner Temple swore never to take a case against Dudley and to offer him their legal services whenever required. This pledge was always honored, and in 1576 the Inner Temple Parliament referred to Dudley as the “chief governor of this House.”[56] The play was partially documented by Gerard Legh in his Accedens of Armory, a book of heraldry woodcuts, which described Dudley as bearing the shield of Pallas, and being Prince Pallaphilos, the second Perseus, lieutenant of the goddess Pallas Athena—personifying Queen Elizabeth—and patron of the order of Pegasus, the horse of honor.[57]

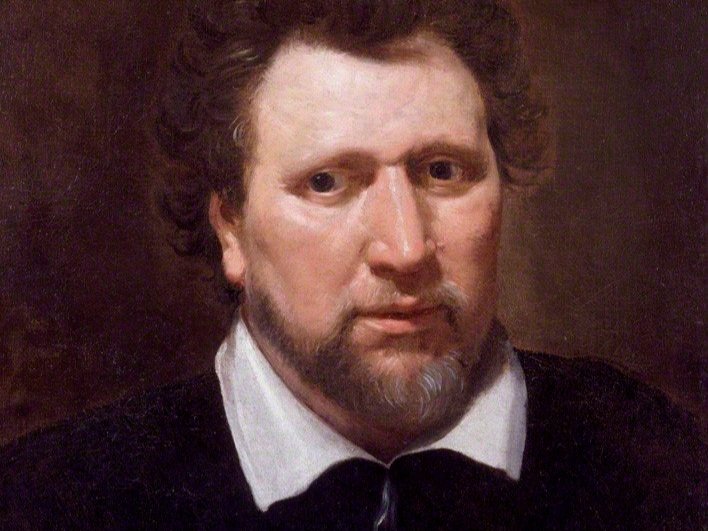

Ben Jonson (1572 – 1637)

Printed in 1688 from a manuscript apparently passed down from the 1590s, the Gesta Grayorum is an account of the Christmas revels by the law students at Gray’s Inn in 1594. On 28 January 1594, Bacon took over the role of Treasurer of Gray’s Inn, where he was responsible for the revels. It was decided that the Inn was to be turned into a mock royal court and kingdom, ruled by a “Prince,” in jesting imitation of the royal court of Queen Elizabeth, complete with masques, plays, dances, pageants, ceremonial. The revels, which took place over the Twelve Days of Christmas, were called The Prince of Purpoole and the Honourable Order of the Knights of the Helmet. The title referred to the Manor of Purpoole or Portpoole, the original name of Gray’s Inn. Like the mummers, the theme of these revels centered around the idea of errors being committed, disorder ensuing, and a trial held of the “Sorcerer” responsible, who then restores order.[58]

The entertainment would have included drinking the health of the Prince of Purpoole, usually a student elected Lord of Misrule for the duration of the Festival.[59] In the Inns of Court, the Lord of Misrule was represented by lawyers dressed as a prince: the Prince d’Amour for the Middle Temple, the Prince of the Sophie for the Inner Temple, the Prince of the Grange for Lincoln’s Inn, and the Prince of Purpoole for Gray’s Inn.[60] The Lord of Misrule to John Milton, in a masque of the same name, was the pagan god Comus. In Greek mythology, Comus is the god of festivity and revelry, and the root of the word “comedy.” Ben Jonson associated Comus with Bacchus in Poetaster (1602): “we must live and honor the Gods sometimes, now Bacchus, now Comus, now Priapus.”[61] In Jonson’s Pleasure Reconciled to Virtue, Comus, the god of cheer, the Belly-god appears as a character, riding in triumph with his head crowned with roses. The Neo-Latin play Comus (1610) by Erycus Puteanus was performed in Oxford in 1634.[62] Ben Jonson dedicated Every Man out of His Humor to “the noblest nurseries of humanity and liberty, the INNS OF COURT.”[63]

The Lord of Misrule, who presided over the festivities in grand houses, university colleges and Inns of Court, was sometimes called “Captain Christmas,” “Prince Christmas” or “The Christmas Lord,” being the origin of Father Christmas, and later Santa Claus.[64] With the Christianization of Germanic Europe, numerous traditions were absorbed from Yuletide celebrations into modern Christmas. Odin’s role during the Yuletide has been theorized as having influenced concepts of St. Nicholas, and later Santa Claus.[65] A personified “Christmas” appears in Ben Jonson’s court entertainment Christmas his Masque (1616), also called Christmas His Show, together with his ten children, who are led in, on a string, by Cupid: Carol, Misrule, Gambol, Offering, Wassail, Mumming, New-Year’s-Gift, Post and Pair, and even Minced-Pie and Baby-Cake. Cupid is soon joined by his mother Venus, who lives in Pudding Lane.

Merrymount

A nineteenth-century engraving of Mayflower passenger Cpt. Miles Standish and his men observing the immoral behavior of the Maypole festivities of 1628.

Thomas Morton (c. 1579 – 1647) was an early American colonist from Devon, England, famed for founding the British colony of Merrymount, which was located in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts, and for his work studying Native American culture. Morton maintained contacts with the School of Night, a modern name for a group of men centered on Sir Walter Raleigh that was once referred to in 1592 as the “School of Atheism.”[66] The group supposedly included poets and scientists Christopher Marlowe, George Chapman and Thomas Harriot. It was alleged that each of these men studied science, philosophy, and religion, and all were suspected of atheism. Marlowe was the author of Doctor Faustus, which is the most controversial Elizabethan play outside of Shakespeare. It is based on the German story of Faust, a highly successful scholar who is dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil, and exchange his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. There is no firm evidence that all of these men were known to each other, but speculation about their connections features prominently in some writing about the Elizabethan era.

In the late 1590s, Morton studied law at London's Clifford’s Inn, where he was exposed to the “libertine culture” of the Inns of Court, where bawdy revels included Gesta Grayorum performances associated with Francis Bacon and Shakespeare. It is likely there that he met Ben Jonson, who would remain a friend throughout his life. Morton eventually settled into the service of Ferdinando Gorges, an associate of Sir Walter Raleigh, who was governor of the English port of Plymouth and a major colonial entrepreneur. Gorges had been part of Robert Devereux’s Essex Conspiracy, Essex’s Rebellion was an unsuccessful rebellion led by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, in 1601 against Elizabeth I of England and the court faction led by Sir Robert Cecil to gain further influence at court. Gorges escaped punishment by testifying against the main conspirators who were executed for treason.

By 1626, Morton had established a trading post at a place called Merrymount, on the site of modern-day Quincy, Massachusetts. Scandalous rumors spread of debauchery at Merrymount, including immoral sexual liaisons with native women and drunken orgies in honor of Bacchus and Aphrodite, or as the Puritan Governor William Bradford wrote in his history Of Plymouth Plantation, “They… set up a May-pole, drinking and dancing about it many days together, inviting the Indian women for their consorts, dancing and frisking together (like so many fairies, or furies rather) and worse practices. As if they had anew revived & celebrated the feasts of ye Roman Goddess Flora, or ye beastly practices of ye mad Bacchanalians.”[67]

Morton declared himself “Lord of Misrule,” of the Feast of Fools. As historians note, the name “Merrymount” can also refer to the Latin phrase Mas Maris meaning “erect phallus.”[68] On May 1, 1627, Merrymount decided to throw a party in the manner of Merrie Olde England. The Mayday festival, the “Revels of New Canaan,” inspired by “Cupid’s mother”—with its “pagan odes” to Neptune and Triton (as well as Venus and her lustful children, Cupid, Hymen and Priapus), its drinking song, and its erection of a huge 80-foot Maypole, topped with deer antlers—appalled the “Princes of Limbo,” as Morton referred to his Puritan neighbors. After a second Maypole party the following year, Myles Standish led a party of armed men to Merrymount, and arrested Morton. Morton returned to New England in 1629, where he wrote New English Canaan, that praised the wisdom and humanity of the Indians but mocked the Puritans, and made Morton a celebrity in political circles.[69]

The second 1628 Mayday, “Revels of New Canaan,” inspired by “Cupid’s mother.” with its “pagan odes” to Neptune and Triton as well as Venus and her lustful children, Cupid, Hymen and Priapus, its drinking song, and its erection of a huge Maypole, topped with deer antlers, again scandalized his Puritan neighbours, whom he referred to as “Princes of Limbo.” The Plymouth militia under Myles Standish took the town the following June with little resistance, chopped down the Maypole and arrested Morton. He was marooned on the deserted Isles of Shoals, off the coast of New Hampshire, where he was essentially left to starve. However, he was supplied with food by friendly natives from the mainland, and he eventually gained strength to escape to England. The Merrymount community survived without Morton for another year, but was renamed Mount Dagon by the Puritans, after the Semitic sea god. During the severe winter famine of 1629, residents of New Salem under John Endecott raided Mount Dagon’s corn supplies and destroyed what was left of the Maypole, denouncing it as a pagan idol and calling it the “Calf of Horeb.” To the disappointment of the Pilgrims, Morton faced no legal action back in England. Instead, he returned to New England in 1629, settling in Massachusetts just as Winthrop and his allies were trying to launch their new colony. Morton was rearrested, again put on trial and banished from the colonies. The following year the colony of Mount Dagon was burned to the ground and Morton again shipped back to England.

Over the years, other rebels and free-thinkers have lived in Merrymount, which became Wollaston. The midwife Anne Hutchinson, who challenged the Puritan theocracy, lived there with her husband when they first arrived in New England in 1634. Hutchinson, who saw herself as a prophetess, became in involved in the Antinomian Controversy, which pitted John Winthrop and most of the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s Puritans against the Free Grace theology of her mentor John Cotton. John Hancock was born there, and John Quincy Adams, whose property in Quincy included the site of Mar-re Mount and who communicated to Thomas Jefferson his excitement upon finding a copy of New English Canaan after half a century.[70] Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story “The May-Pole of Merry Mount” in his Twice-Told Tales (1837) and J. L. Motley’s Merry Mount (1849) are based on Morton’s colonial career.

Mystick Krewe of Comus

New Orleans Mardis Gras

Albert Pike (1809 – 1891), Sovereign Commander Grand Master of the Supreme Council of Scottish Rite Freemasonry in Charleston, South Carolina, and the reputed founder of the notorious Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

Mimi L. Eustis published a website in 2005, titled Mardi Gras Secrets, to share the deathbed confessions of her father Samuel Todd Churchill, a high-level member of the Mystick Krewe of Comus, a secret society founded in 1856 by Judah P. Benjamin and Albert Pike in order to meet and communicate the plans of the Rothschilds. Civil War General Albert Pike was Sovereign Commander Grand Master of the Supreme Council of Scottish Rite Freemasonry in Charleston, South Carolina, and the reputed founder of the notorious Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

The Mystick Krewe of Comus, which is named after John Milton’s Lord of Misrule in his masque Comus, is oldest continuous organization of New Orleans Mardi Gras, a modern adaptation of the Feast of Fools festival. Prior to the advent of Comus, Carnival celebrations in New Orleans were mostly confined to the Roman Catholic Creole community, and parades were irregular and often very informally organized.

The Mardi Gras was originally a Catholic festive season that occurs before the liturgical season of Lent. From Italy, Carnival traditions spread to Spain, Portugal, and France, and from France to New France in North America. From Spain and Portugal, it spread with colonization to the Caribbean and Latin America. Most Louisiana cities which were under French control at one time or another, also hold Carnival celebrations. The most widely known, elaborate, and popular US events are in New Orleans where Carnival season is referred to as Mardi Gras.

Although officially, the Krewe of Comus claims to descend from the Cowbellion de Rakin Society of Mobile, Alabama, Eustis’ father claimed the society was founded by Yankee bankers from New England, who used the society as a front for the House of Rothschild, as well as for Skull and Bones, which was a branch of the Bavarian Illuminati. Passage into the secret of the code number 33, the highest stages of membership within the Skull and Bones society, required participation in the ritual “Killing of the King.” Eustis says her father emphasized that most Masons below the 3º remained in ignorance, while those to who rose past the 33º did so by participating in the “Killing of the King” ritual.

According to Eustis, William H. Russell, the founder of Skull and Bones, had a key partner by the name of Caleb Cushing, who served as a U.S. Congressman from Massachusetts and Attorney General under President Franklin Pierce. Cushing was involved in the secret “Killing of the King” of Presidents William Henry Harrison (1773 –1841) in 1841, and Zachary Taylor (1784 – 1850) in 1850, who had both opposed admitting Texas and California as slave states. Cushing dispatched Albert Pike, where his mission was to further the cause of slavery and to foster the Civil War, and to establish a line of communication with other fellow Illuminati. Pike was chosen by Cushing to head an Illuminati branch in New Orleans and to establish a New World order. Pike moved his law office to New Orleans in 1853 and was made Masonic Special Deputy of the Supreme Council of Louisiana on April 25, 1857.

Cushing, recounted Eustis, dispatched Albert Pike to Arkansas and Louisiana. Pike’s mission was to further the cause of slavery and to foment a and America civil war, and to establish a line of communication with other fellow Illuminati. Pike was chosen by Cushing to head an Illuminati branch in New Orleans and to establish a New World order. Pike moved his law office to New Orleans in 1853 and was made Masonic Special Deputy of the Supreme Council of Louisiana on April 25, 1857. Eustis further asserts, Pike and Judah P. Benjamin needed a secret society in order to foster a civil war in the United States and to establish the House of Rothschild, for which purpose they founded the Mystick Krewe of Comus in that same year.

Young American Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804 – 1864)

The Mystick Krewe of Comus was founded to observe Mardi Gras in a more organized fashion. The second-oldest krewe in the New Orleans Mardi Gras is the Krewe of Momus, Son of Night & Lord of Misrule, which was founded in 1872. The Knights of Momus has operated continuously since its founding, and remains a secret society. The 1877 parade theme, “Hades, A Dream of Momus,” caused an uproar when it took aim at the Reconstruction government established in New Orleans after the Civil War. Attempts at retribution by local authorities were largely unsuccessful due to the secrecy of the membership. Momus’s 1878 float was inspired by Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The inspiration for the Krewe of Comus came from Rosicrucian author John Milton’s Lord of Misrule in his masque Comus. The rebellious Thomas Morton declared himself “Lord of Misrule” during the pagan revelry in Merrymount in 1627, and his fellow celebrants were described by Young American Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804 – 1864) in The May-Pole of Merry Mount (1837) as a “crew of Comus.” Hawthorne was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, where his ancestors included John Hathorne, the only judge involved in the Salem witch trials who never repented of his actions. Much of Hawthorne’s fiction, such as The Scarlet Letter is set in seventeenth-century Salem. In 1851, Hawthorne published The House of the Seven Gables, a Gothic novel whose setting was inspired by the Turner-Ingersoll Mansion, a gabled house in Salem, belonging to Hawthorne’s cousin Susanna Ingersoll, and by his ancestors who had played a part in the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. In Young Goodman Brown, the main character is led through a forest at night by the Devil, appearing as man who carries a black serpent-shaped staff. Goodman is led to a coven where the townspeople of Salem are assembled, including those who had a reputation for Christian piety, in-mixed with criminals and others of lesser reputations, as well as Indian priests. Herman Melville said the novel was “as deep as Dante” and Henry James called it a “magnificent little romance.”[71]

Edgar Allan Poe, a fellow contributor to the Democratic Review, referred to Hawthorne’s short stories as “the products of a truly imaginative intellect.”[72] Poe’s gothic works are replete with occult symbolism. Poe’s Cask of Amontillado enacts a Masonic ritual in a way that would be evident only to Masons. The story is set in an unnamed Italian city, told from the perspective of a man named Montresor plots to murder his friend Fortunato during Carnevale (Mardi Gras), while the man is drunk and wearing a jester’s motley. who, he believes, has insulted him. According to Robert Con Davis-Undiano, “the plot of story, from Montresor’s initial meeting with Fortunato during Italian Carnevale, through Fortunato’s final entombment, itself enacts an initiation rite for Freemasonry.”[73]

Romantic Satanists

Along with the portrait of Priestley, The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli (1781) hung above Johnson's dinner guests.

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797)

The circle of radical artists around Joseph Johnson (1738 – 1809) are known as Romantic Satanists, for their having the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost as a heroic figure who rebelled against “divinely ordained” authority.[74] hnson is best known for publishing the works of radical thinkers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, Thomas Malthus, Illuminatus Thomas Paine, as well as religious dissenters such as Joseph Priestley, a member Royal Society and of Lord Shelburne’s “Bowood circle,” along with Freemason Richard Price, who was a friend of Franklin and a key supporter of the American Revolution.

Johnson became friends with Priestley and Henry Fuseli (1741 – 1825), two relationships that lasted his entire life and enriched his business. In turn, Priestley trusted Johnson to handle his induction into the Royal Society.[75] Hanging above Johnson’s dinner guests, along with a portrait of Priestley, was Henry Fuseli’s famous The Nightmare, depicting a woman swooning with a demonic incubus crouched on her chest. One of Fuseli’s schoolmates with whom he became close friends was Johann Kaspar Lavater, who had challenged Moses Mendelssohn to convert Christianity.[76]

The Romantic Satanists were inspired by Milton’s famous line were Satan declares, “Better to reign in Hell, than to serve in Heav’n.” This attitude was found in Johnson’s friend, artist Henry Fuseli, who portrayed the fallen angel as a classical hero. In 1799, Fuseli exhibited own “Milton Gallery,” a series of 47 paintings from themes from Paradise Lost, with a view to forming a Milton gallery comparable to Boydell’s Shakespeare gallery. William Godwin (1756 – 1836), wrote in Enquiry into Political Justice (1793), where Milton’s Satan persists in his struggle against God even after his fall, and “bore his torments with fortitude, because he disdained to be subdued by despotic power.” Godwin, who is regarded as one of the first exponents of utilitarianism, and the first modern proponent of philosophical anarchism. Godwin was married to Fuseli’s former lover, the philosopher and feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797), best known for A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy.

Johnson introduced Blake to the radical circle of Wollstonecraft, Godwin and Thomas Paine. Wollstonecraft, according to Adriana Craciun, “was among the first in a line of romantic outcasts who modeled themselves on the fallen hero of Paradise Lost.”[77] In A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, explains Craciun, it was the Adversary himself with whom Wollstonecraft identifies. Seeing through Milton’s domestic paradise: “The domestic trifles of the day have afforded matters for cheerful converse,” she writes regarding contemporary perceptions of women’s domesticity. “Similar feelings has Milton’s pleasing picture of paradisiacal happiness ever raised in my mind,” Wollstonecraft adds, “yet, instead of envying the lovely pair [Adam and Eve], I have with conscious dignity, or Satanic pride, turned to hell for sublimer objects.”[78]

After Wollstonecraft’s death, Godwin published a Memoir (1798) of her life, revealing her promiscuous lifestyle, which destroyed her reputation for almost a century. The Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine, a conservative British political periodical, concluded that “the moral sentiments and moral conduct of Mrs. Wollstonecroft [sic], resulting from their principles and theories, exemplify and illustrate JACOBIN MORALITY” and warns parents against rearing their children according to her advice.[79] Such accusations, explains Chandos Michael Brown, in a time of widespread suspicion of the subversive activities of the Jacobins, would have regarded Wollstoncroft as a female Illuminati.[80]

Fuseli’s style had a considerable influence on many younger British artists, including William Blake (1757 – 1827), who was employed by Johnson. Largely unrecognized in his own lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and arts of the Romantic Age, along with William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor. Blake frequented Swedenborg’s New Jerusalem Society, which was influenced by the Kabbalistic sexual practice of Count Zinzendorf. While there is no record of Blake belonging to Freemasonry, he has been universally regarded in the occult as one of its great sages. However, Blake’s biographer Peter Ackroyd noted that according to the lists of grandmasters of the Druid Order, Blake was a grandmaster from 1799 until 1827. Of druidism Blake believed that, “The Egyptian Hieroglyphs, the Greek and the Roman Mythology, and the Modern Freemasonry being the last remnants of it. The honorable Emanuel Swedenborg is the wonderful Restorer of this long lost Secret.”[81] One of his most well-recognized paintings is that of the Ancient of Days of the Kabbalah, holding the Masonic symbol of a compass over a darker void below.

Blake produced the illustrations for an 1808 edition of Paradise Lost. Blake famously wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it.” Blake’s Marriage of Heavan and Hell, explain Per Faxneld and Jesper Aa. Petersen, could be considered the first “satanic” Bible in history.[82] Through the voice of the Devil, Blake parodies and attacks the theology of Emanuel Swedenborg, the cosmology and ethics of Milton’s Paradise Lost, and biblical history and morality as constructed by the “Angels” of the established church and state. The Bible and other religious texts, Blake says, have been responsible for a lot of the misinformation. Although Hell is perceived as full of torment, it actually is a place where free-thinkers revel in the full experience of existence. While he was touring around, Blake says he collected some of the Proverbs of Hell, one of which famously stated: “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” The book ends with the Song of Liberty, a prose poem where Blake uses apocalyptic imagery to incite his readers to embrace the coming revolution.

Frankenstein

Villa Diodati, a house Lord Byron rented by Lake Geneva in Switzerland, Mary, Percy and John Polidori (1795 – 1821) decided to have a competition to see who could write the best horror story, which resulted in Mary’s Frankenstein.

William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft were the parents of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797 – 1851), author of Frankenstein. Mary’s husband Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 – 1822), who wrote Prometheus Unbound, equating the Satan of Milton’s Paradise Lost with Prometheus, the Greek mythological figure Prometheus, who defies the gods and gives fire to humanity, for which he is subjected to eternal punishment and suffering at the hands of Zeus. Percy is regarded by critics as amongst the finest lyric poets in the English language. Percy was expelled from Oxford after he published his Necessity of Atheism in 1811. Shelley was inspired by Spinoza to write his essay “The Necessity of Atheism,” which was circulated to all the heads of Oxford colleges at the University, where it caused great controversy. Shelley quotes Spinoza in his note in Canto VII of Queen Mab, published two years later and based on the essay. There, Shelley qualifies his definition of atheism in relation to Spinoza’s pantheism:

There Is No God. This negation must be understood solely to affect a creative Deity. The hypothesis of a pervading Spirit co-eternal with the universe remains unshaken.[83]

In his authoritative biography on Shelley, James Bieris notes that while Shelley was at Eton Shelley spent much of his leisure time reading on occult science, and spent his money on books on witchcraft and magic and on scientific instruments and materials. Also at Eton, Shelley was reported to have tried to “raise a ghost,” taking a proscribed skull which he drank from three time, fearing that the devil was following him, but no ghost appeared.[84] In his youth, Shelley had fallen under the influence of Dr. James Lind, a member of the Lunar Society and considered the modern-day Paracelsus. In fact, among Shelley’s favorite topics for research was Paracelsus, in addition to magic and alchemy. Among Percy Shelley’s best-known works are Prometheus Unbound, and The Rosicrucian, A Romance, a Gothic horror novel where the main character Wolfstein, a solitary wanderer, encounters Ginotti, an alchemist of the Rosicrucian or Rose Cross Order who seeks to impart the secret of immortality.

Shelley read the anti-religious works of Lucretius and the Illuminatus Condorcet.[85] Percy Shelley read Barruel’s Memoirs “again and again… [being] particularly taken with the conspiratorial account of the Illuminati.”[86] At Oxford, Shelley became friends with Thomas Jefferson Hogg, his future biographer, who reported, “He used to read aloud to me with rapturous enthusiasm the wondrous tales of German Illuminati, and he was disappointed, sometimes even displeased, when I expressed doubt or disbelief.”[87] On March 2, 1811, Shelley, who thought of creating his own “association” along similar lines, sent a letter to the editor of the Examiner in which he expressed his desire of “applying the machinery of Illuminism.”[88] Likewise, writes Mary Shelley’s biographer, Miranda Seymour, “Sitting on the shores of Lake Lucerne, Mary had been introduced to one of Shelley’s favorite books, the Abbé Barruel’s Memoirs… Here, Barruel traced the birth of ‘the monster called Jacobin’ to the secret society of the Illuminati at Ingolstadt. Ingolstadt is where Mary decided to send Victor Frankenstein to university; Ingolstadt is where he animates his creature…”[89]

English Romantic poetry is believed to have reached its zenith in the works of Keats, Shelley and Lord Byron (1788 – 1824).[90] Mary and Percy Shelley were also closely associated Byron, who is described as the most flamboyant and notorious of the leading Romantics. Byron was celebrated during his lifetime for aristocratic excesses, including huge debts, numerous love affairs with both sexes, rumors of a scandalous incestuous liaison with his half-sister, and self-imposed exile. Byron travelled all over Europe, especially in Italy where he lived for seven years and became a member of the Carbonari. He later joined the Greek War of Independence fighting the Ottoman Empire, for which Greeks revere him as a national hero.[91] Influenced by Milton’s Paradise Lost, Byron wrote Cain: A Mystery in 1821, provoking an uproar because the play dramatized the story of Cain and Abel from the point of view of Cain, who is inspired by Lucifer to protest against God.

In 1816, at the Villa Diodati, a house Byron rented by Lake Geneva in Switzerland, Mary, Percy and John Polidori (1795 – 1821) decided to have a competition to see who could write the best horror story, which resulted in Mary’s Frankenstein. Polidori was an English writer and physician, known for his associations with the Romantic movement and credited by some as the creator of the vampire genre of fantasy fiction. His most successful work was the short story The Vampyre (1819), produced by the same writing contest, and the first published modern vampire story.

The fable of the alchemically-created homunculus, which was related to the Jewish legend of the golem, may have been central in Shelley’s novel Frankenstein. Professor Radu Florescu suggests that Johann Conrad Dippel, an alchemist born in Castle Frankenstein, might have been the inspiration for Victor Frankenstein. Victor Frankenstein, the protagonist of Mary’s novel, admits to having been inspired by Agrippa, Paracelsus and Albertus Magnus, all magicians and among the most celebrated figures in Western occult tradition. Victor begins his account by announcing, “I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.”

Mary Shelley was inspired by Frankenstein Castle, where two centuries before an alchemist was engaged in experiments. Frankenstein Castle is on a hilltop in the Odenwald overlooking the city of Darmstadt in Germany. The castle gained international attention when the SyFy TV-Show Ghost Hunters International produced an entire episode about the castle in 2008, after which the team became convinced that there was some sort of paranormal activity going on. Frankenstein Castle is associated with numerous occult legends, including that of a knight named Lord Georg who saved local villagers from a dragon, and a fountain of youth where in the first full-moon night after Walpurgis Night old women from the nearby villages had to undergo tests of courage. The one who succeeded was returned to the age she had been in the night of her wedding. On Mount Ilbes, in the forest behind Frankenstein Castle, compasses do not work properly due to magnetic stone formations. Legend has it that Mount Ilbes is the second most important meeting place for witches in Germany after Mount Brocken in the Harz. In the late seventeenth century, Johann Conrad Dippel stayed at Frankenstein, where he was rumored to have practiced alchemical experiments on corpses that he exhumed, and that a local cleric warned his parish that Dippel had created a monster that was brought to life by a bolt of lightning. Local people still claim this to have actually happened and that this tale was related to Shelley’s stepmother by the Grimm brothers, the German fairy-tale writers.[92]

Hail Santa

Illustrated scene from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol

Charles Dickens (1812 –1870)

Charles Dickens’ 1843 novel A Christmas Carol was highly influential, and has been credited both with reviving interest in Christmas in England and with shaping the themes associated with it.[93] Dickens was a close friend of Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803 – 1873), the pre-eminent personality of the Occult Revival, and the “Great Patron” of the Masonic research group known as the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia (SRIA), which was restricted to high-ranking Freemasons. Bulwer-Lytton was also closely acquainted with Eliphas Lévi, who would become one of the most important esoteric writers of all time. In 1855, under his civil name of Constant, Levi published a series of articles in the Revue entitled “The Kabbalistic Origins of Christianity” and the Kabbalah as the “Source of all Dogmas,” which was the first time that he expounded his “Kabbalistic” theories to a wider socialist readership. Albert Pike also wrote lectures for all the degrees which were published in 1871 under the title Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, which was mostly plagiarized from Eliphas Lévi’s Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie.

Pike, along with Otto von Bismarck (1815 – 1898) and Giuseppe Mazzini (1807 – 1872)—who was reputed to have been Weishaupt’s successor as head of the Illuminati[94]—completed an agreement to create a supreme universal rite of Masonry that would arch over all the other rites.[95] Pike, in honor of the Templar idol Baphomet, named the order the New and Reformed Palladian Rite or New and Reformed Palladium. The Palladian Rite, it was the pinnacle of Masonic power, an international alliance to bring in the Grand Lodges, the Grand Orient, the ninety-seven degrees of Memphis and Misraim of Count Cagliostro, also known as the Ancient and Primitive Rite, and the Scottish Rite, or the Ancient and Accepted Rite.

Lévi collaborated closely with Charles Nodier (1780 – 1844), a purported Grand Master of the Priory of Sion, who was an influential French author and librarian who introduced a younger generation of Romanticists to the conte fantastique, gothic literature, and vampire tales. Nodier successfully adapted John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” for the stage. “The Vampyre” was taken from the story Lord Byron told as part of a contest among Polidori, Mary Shelley, Lord Byron, and Percy Shelley, which also produced the novel Frankenstein.

Mary Shelley was on friendly terms with John Howard Payne (1791 – 1852), an American actor and poet who enjoyed nearly two decades of a theatrical career and success in London. Payne is today most remembered as the creator of “Home! Sweet Home!.” After his return to the United States in 1832, Payne spent time with the Cherokee Indians in the Southeast and published a theory that suggested their origin as one of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Payne’s belief was shared by other figures of the early American period, including Benjamin Franklin.[96] Payne had become infatuated with Shelley, but lost interest when he realized she hoped only to use him to attract the attention of his friend, American short-story writer Washington Irving (1783 – 1859).[97] Irving was one of the first American writers to earn fame in Europe, and thus encouraged other American authors such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Herman Melville and Edgar Allan Poe. Irving was also admired by number of British writers, including Lord Byron, Thomas Campbell, Charles Dickens, Mary Shelley, Francis Jeffrey and Walter Scott, who became a lifelong personal friend.

Washington Irving (1783 – 1859)

Christmas celebrations were first revived by Francis Bacon at the Inns of Court, where they were presided over by the Lord of Misrule, borrowed directly from the ancient Saturnalia and its worship of Saturn, or Satan.[98] Following the Protestant Reformation, many of the new denominations continued to celebrate the holiday. In 1629, the John Milton penned On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity, a poem that has since been read by many during Christmastide.[99] However, when the Puritans took control of government in the mid-1640s they made concerted efforts to abolish Christmas and to outlaw its traditional customs. In 1647, parliament passed an Ordinance for Abolishing of Festivals which formally abolished Christmas in its entirety, along with the other traditional church festivals of Easter and Whitsun.

Following the Restoration in 1660, most traditional Christmas celebrations were revived, and during the Victorian period, they enjoyed a significant revival, including the figure of Father Christmas. In the early nineteenth century, Christmas festivities became widespread with the rise of the Oxford Movement in the Church of England which emphasized the centrality of Christmas in Christianity, along with Irving, Dickens, and other authors emphasizing children, gift-giving, and Santa Claus or Father Christmas.[100] In the 1820s, interest in Christmas was revived in America by several short stories by Irving which appeared in his The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. and “Old Christmas.” Irving’s stories depicted English Christmas festivities he experienced while staying in Aston Hall in Birmingham, that had largely been abandoned. As a format for his stories, Irving used the tract Vindication of Christmas (1652) of Old English Christmas traditions, that he had transcribed into his journal.[101]

Irving’s friend, Clement Clarke Moore (1779 – 1863), was the author of A Visit from St. Nicholas, more commonly known as ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas, a poem first published anonymously in 1823, through which modern ideas of Santa Claus were popularized. “St. Nick” is described as being “chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf” covered in soot, with “a little round belly,” riding a “miniature sleigh” pulled by “tiny reindeer” named: Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder and Blixem, which came from the old Dutch words for thunder and lightning, which were later changed to the more German sounding Donner and Blitzen. Of the numerous mythological connections between Santa and Satan, Jeffrey Burton Russell explains in The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History:

The Devil comes from the north, domain of darkness and punishing cold. Curious connections exist between Satan and Santa Claus (Saint Nicholas). The Devil lives in the far north and drives reindeer; he wears a suit of red fur; he goes down chimneys in the guise of Black Jack or the Black Man covered in soot; as Black Peter he carries a large sack into which he pops sins or sinners (including naughty children); he carries a stick or cane to thrash the guilty (now he merely brings candy canes); he flies through the air with the help of strange animals; food and wine are left out for him as a bribe to secure his favors. The Devil's nickname (!) “Old Nick” derives directly from Saint Nicholas. Nicholas was often associated with fertility cults, hence with fruit, nuts, and fruitcake, his characteristic gifts.[102]

Irving’s The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. also included the short stories for which he is best known, “Rip Van Winkle” (1819) and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820), which was especially popular during Halloween because of a character known as the Headless Horseman believed to be a Hessian soldier who was decapitated by a cannonball in battle. In 1824, Irving published the collection of essays Tales of a Traveller, including the short story “The Devil and Tom Walker,” a story very similar to the German legend of Faust. The story first recounts the legend of the pirate William Kidd, who is rumored to have buried a large treasure in a forest in colonial Massachusetts. Kidd made a deal with the devil, referred to as “Old Scratch” and “the Black Man” in the story, to protect his money.

[1] K. Karbiener & G. Stade. Encyclopedia of British Writers, 1800 to the Present, Volume 2, (Infobase Publishing, 2009), pp. 188-190.

[2] James Frazer. The Golden Bough. Chapter 24 - The Killing of the Divine King and Chapter 58 - Human Scapegoats in Classical Antiquity.

[3] Dorothy Morrison. Yule: A Celebration of Light and Warmth (St. Paul, Minn: Llewellyn Publications). p. 4.

[4] H. D. Muller. “Mythologie der griech.” Stimme, II 39 f; K. O. Miiller, Aeschylos, Eumeniden, p. 146 f; . Stengel, “Die griech,” Sakralalterthimer, S. 87; cited in Arthur Fairbanks, “The Chthonic Gods of Greek Religion,” The American Journal of Philology , Vol. 21, No. 3 (1900), pp. 241-259.

[5] M. L. West. The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth (Oxford: Claredon Press, 1997), p. 277.

[6] “Cronus.” Encyclopædia Britannica (Encyclopædia Britannica Ind, September 26, 2018).

[7] West. The East Face of Helicon, p. 277.

[8] Book XX, Chap. I.

[9] West. The East Face of Helicon, p. 302.

[10] Ibid., p. 298-99.

[11] Ibid., p. 490.

[12] James Frazer. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (Third Edition, Vol. 09 of 12) 5. Saturnalia in Western Asia.

[13] James Frazer. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (Third Edition, Vol. 09 of 12). “The Babylonian Festival of the Sacaee.”

[14] Jan Bremmer. “Ritual.” in Religions of the Ancient World (Belknap Press, 2004), p. 38.

[15] Livy 22.1.20; Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.10.18; Robert E. A. Palmer. Rome and Carthage at Peace (Historia – Einzelschriften) (Stuttgart, Germany: Franz Steiner, 1997), pp. 63–64.

[16] Roel van den Broek. “The Sarapis Oracle in Macrobius Sat., I, 20, 16–17,” in Hommages à Maarten J. Vermaseren (Brill, 1978), vol. 1, p. 123ff.

[17] James Frazer. The New Golden Bough, ed. Theodor H. Gaster, part 7 “Between Old and New: Periods of License” (New York: Criterion Books, 1959).

[18] Michael Haag. The Templars. The History & the Myth (Profile Books, 2008), p. 257.

[19] Napier. A to Z of the Knights Templar.

[20] Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most & Salvatore Settis. “Bacchanalia and Saturnalia.” The Classical Tradition (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010). p. 116.

[21] Craig A. Williams. Martial: Epigrams Book Two (Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 259.

[22] Ebbe Schön. Asa-Tors hammare, Gudar och jättar i tro och tradition (Fält & Hässler, Värnamo, 2004).

[23] George Harley McKnight. St. Nicholas: His Legend and His Role in the Christmas Celebration and Other Popular Customs (1917) pp. 24–26, 138–139.

[24] Jeffrey Burton Russell. The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History (Ithica: Cornell University Press, 1988), p. 114.

[25] Grafton, Most & Settis. “Bacchanalia and Saturnalia.” p. 116.

[26] Clement A. Miles. Christmas in Ritual and Tradition (Xist Publishing, 2016). p. 108.

[27] Carl Gustav Jung. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (New York: Bolingen, 1959), p. 257.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Grafton, Most & Settis. “Bacchanalia and Saturnalia,” p. 116.

[30] Ibid.

[31] James Edwin Thorold Rogers. Bible Folk-lore: A Study in Comparative Mythology (New York: J.W. Bouton, 1884), p. 346.

[32] John Cleland. Fanny Hill, or, Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (New York: Penguin Classics, 1985).

[33] Ibid., p. 346.

[34] Tucker Brooke (December 1946). “Latin Drama in Renaissance England.” A Journal of English Literary History. 13 (4): 233–240.

[35] William Dugdale & William Herbert. Antiquities of the Inns of court and chancery: containing historical and descriptive sketches relative to their original foundation, customs, ceremonies, buildings, government, &c., &c., with a concise history of the English law (London: Vernor and Hood, 1804), p. 191.

[36] Robert Richard Pearce. History of the Inns of Court and Chancery: With Notices of Their Ancient Discipline, Rules, Orders, and Customs, Readings, Moots, Masques, Revels, and Entertainments (R. Bentley, 1848). p. 219

[37] Francis Bacon and His Times (Spedding 1878.) Gray’s Inn Revel. Nichol’s Progresses of Queen Elizabeth; cited in Martin Pares. “Francis Bacon and the Knights of the Helmet.” American Bar Association Journal, Vol. 46, No. 4 (APRIL 1960), p. 405.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Gargantua and Pantagruel, Book 5, Chapter 8.

[40] Erasmus. Adagia 2.10.74 (Orci galea).

[41] Francis Bacon. Essays Civil and Moral 21, “Of Delays.”

[42] Alfred Dodd. Francis Bacon’s Personal Life Story (Rider, 1986 ), p. 131.

[43] Hagger. The Secret Founding of America. Kindle Locations 1632-1633.

[44] Alfred Dodd. Francis Bacon’s Personal Life Story (Rider, 1986 ), p. 131.

[45] Francis Bacon and His Times (Spedding, 1878).

[46] A. Wigfall Green. The Inns of Court and Early English Drama (New York: Benjamin Blom, 1931).

[47] Ibid.

[48] Frederick S. Boas. University Drama in the Tudor Age (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1914), p. 25.

[49] Henry Glassie. All Silver and No Brass, An Irish Christmas Mumming (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1976). p. 224.

[50] Peter Thomas Millington. The Origins and Development of English Folk Plays, National Centre for English Cultural Tradition (University of Sheffield, 2002), pp. 22, 139.

[51] “Mommerie.” International Encyclopedia of Dance 1998, Vol. 4 (Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 448-9.

[52] Francisco Rodríguez Adrados. History of the Graeco-latin Fable, Vol.3, (Leident: Brill NL, 2003), pp.131-3.

[53] Hermotimus or the Rival Philosophies, p. 52.

[54] Richard Henry Popkin. The Columbia History of Western Philosophy (Columbia University 2013), pp. 320-1.

[55] “Gray’s Inn.” Bar Council. Retrieved from http://www.barcouncil.org.uk/about/innsofcourt/graysinn/

[56] Marie Axton. “Robert Dudley and the Inner Temple Revels.” The Historical Journal (Cambridge University Press, 1970). p. 365.

[57] Ibid., p. 368.

[58] Peter Dawkins. “The Life of Sir Francis Bacon.” Francis Bacon Research Trust (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.fbrt.org.uk/pages/essays/Life_of_Sir_Francis_Bacon.pdf

[59] “Francis Bacon and the Origins of an Ancient Toast at Gray’s Inn.” Graya no. 131, p. 41. Gray’s Inn. Retrieved from https://www.graysinn.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/members/Gray%27s%20Inn%20-%20Graya%20131%20Bacon.pdf

[60] Peter Dawkins. Twelfth Night: The Wisdom of Shakespeare (Oxfordshire: The Francis Bacon Research Trust, Feb. 2, 2015).

[61] 3.4.114-16.

[62] Stella P. Revard. John Milton Complete Shorter Poems (John Wiley & Sons, May 4, 2012), p. 90 n. 20.

[63] A. Wigfall Green. The Inns of Court and Early English Drama (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1931), p. 6-12.

[64] Jacqueline Simpson & Steve Roud. A Dictionary of English Folklore (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 119–120.

[65] George Harley McKnight. St. Nicholas: His Legend and His Role in the Christmas Celebration and Other Popular Customs (1917) pp. 24–26, 138–139.

[66] Frederick Samuel Boas. Christopher Marlowe: a biographical and critical study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940).

[67] “The Maypole That Infuriated the Puritans.” New England Historical Society (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/maypole-infuriated-puritans/

[68] Thomas Morton. New English Canaan. ed. Jack Dempsey (Stoneham, MA: Jack Dempsey, 2000), p. 134, n. 446.

[69] “The Maypole That Infuriated the Puritans.”

[70] David A. Lupher “Thomas Morton of Ma-re Mount: The ‘Lady of Learning’ versus ‘Elephants of Wit’.” Greeks, Romans, and Pilgrims (Leiden: Brill, 2017), p. 82.

[71] Edwin Haviland Miller. Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991), p. 119.

[72] Arthur Hobson Quinn. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), p. 334.

[73] Robert Con Davis-Undiano. “Poe and the American Affiliation with Freemasonry.” symplokē, Vol. 7, No. 1/2, Affiliation (1999), p. 125.

[74] Per Faxneld & Jesper Aa. Petersen. The Devil’s Party: Satanism in Modernity (Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 42.

[75] Chard, Leslie. “Bookseller to publisher: Joseph Johnson and the English book trade, 1760–1810.” The Library. 5th series. 32 (1977), p. 150.

[76] “Fuseli, Henry.” In Hugh Chisholm (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1911).

[77] Adriana Craciun. “Romantic Satanism and the Rise of Nineteenth-Century Women's Poetry Author(s).” New Literary History, Autumn, 2003, Vol. 34, No. 4, Multicultural Essays (Autumn, 2003), pp. 703.